For 27 years, Mexican newspaper Norte de Ciudad Juarez employed over 125 journalists and a team of a dozen photographers to cover life in the border city of Juarez.

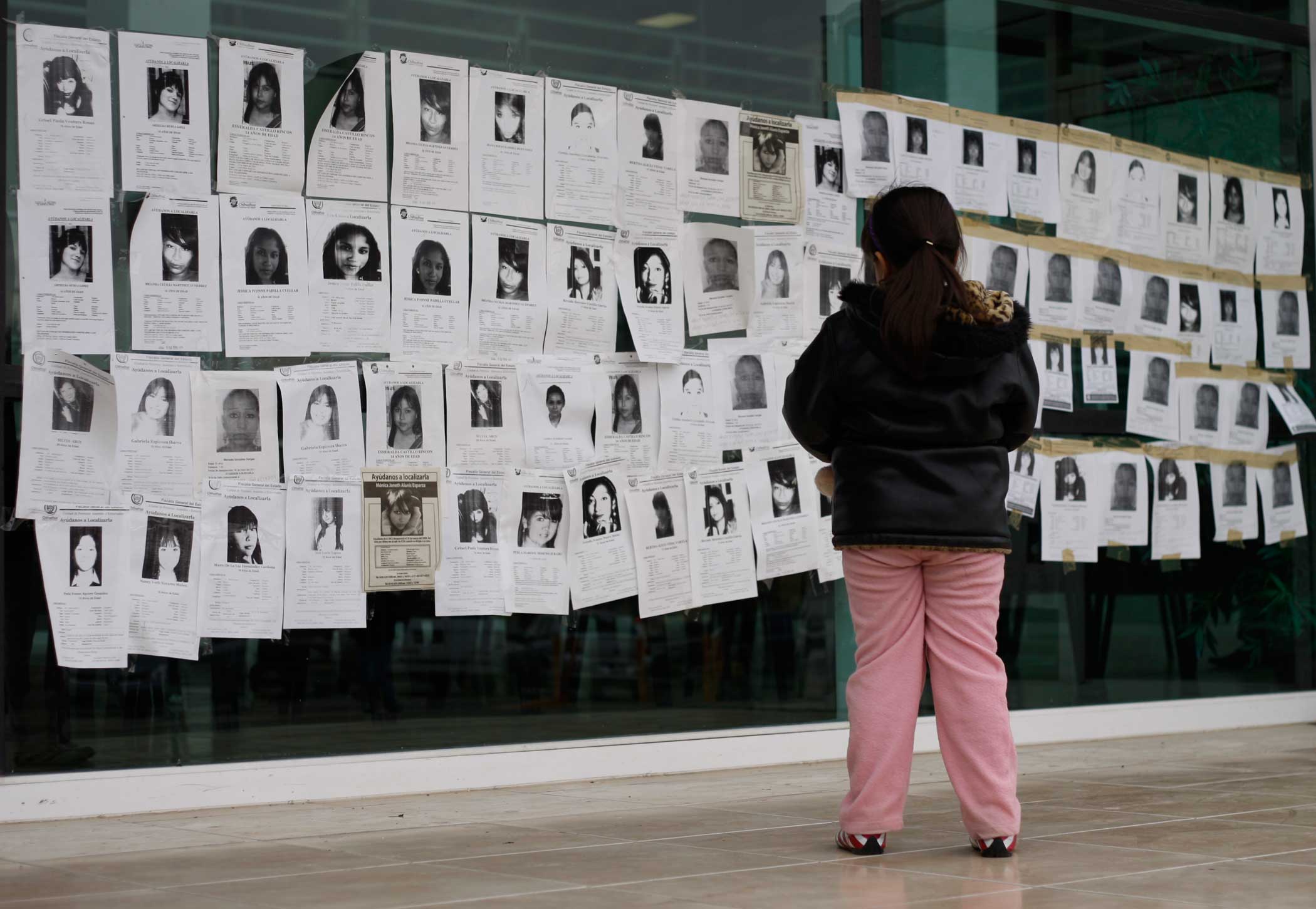

The lives of the newspaper’s journalists were often threatened, but the assassination of Miroslava Breach was a horror too far. The senior reporter was shot dead as she pulled her car out of her garage with one of her kids inside. A sign was left at the crime scene that read “tattletale.”

After 27 years of service, its founder Oscar Cantu had had enough. “We have 99.95% impunity in Mexico. I realized if we keep doing what we are doing we are not going to get results.” Cantu felt he could no longer guarantee the safety of his journalists, and without that security they could no longer safely conduct critical journalism. So he closed down both the print and digital publications of the regional newspaper. “I closed in protest,” he says.

Over a long career, Miroslava had reported on organized crime, corruption and human rights issues for La Journada, a national newspaper and Norte de Juarez. Cantu worked closely with Breach throughout her career. “I truly believe we lost one of the best journalists that we had in the state of Chihuaua” he tells TIME. “It was a very clear message, she was a strategic target. I have never been so emotionally touched as I had regarding Miroslava. I believe I was the last person that she talked to the night before.”

In 1990, Cantu moved his paper from Chihuaua City to Juarez because he felt the citizens there needed a voice. “To defend ourselves against politicians there is no better tool than public opinion.” At the time of Norte’s closure, its distribution had grown to 35,000, becoming the largest newspaper in Chihuahua, Mexico’s largest state. It employed 300 people including 125 journalists.

Norte had a dozen staff photographers, but was down to only a few when it closed. Juan Carlos Hernández López, a photographer and graphic reporter for the paper was on the team covering Miroslava’s death. During their reporting, they say they were followed by at least four people who were taking pictures of them and asking locals about their reporting.

López also spoke to TIME about less subtle encounters that he claimed happened regularly. Last August, as he covered the divorce proceedings of a business magnate Juan was pushed to the ground by one of the guards. He was then offered 60,000 pesos (approximately $3,200) to delete the photograph he had succeeded in taking, López says. Instead, Norte published the photo the next day.

The worldwide reaction to the paper’s closure surprised even Cantu. “For almost 10 days. From all parts of the world. The secretary of the interior came to visit that they were going to do everything they could to get the criminals. I haven’t seen any results from them.”

Despite closing the publication, Cantu still employs the majority of the newsroom to work on important projects that they had begun before Norte closed. “These are stories that don’t really have a deadline. There are one or two stories that are very interesting and we’re trying to figure out what we can do to get them out.”

Cantu is hoping to find a way to reopen the newspaper as a community project. It is unclear where exactly the funding will come from, but he hopes the local population it has helped to keep informed for all of these years will help to keep Norte — and its tradition of reporting — alive.

Josh Raab is a multimedia editor at TIME. Follow him on Instagram and Twitter.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com