Since the attack at Charlie Hebdo magazine’s office in Paris in January 2015 cartoonists have in many ways become emblematic of the struggle to defend the inalienable right to freedom of expression.

Cartoonists’ stock in trade is to satirize, mock and even to insult the ideas and values of others. As such, they will be among the first to feel the ire of those parts of society who are most sensitive, sometimes with good reason, as might be the case with minority groups. However if those in power are overly thin-skinned, cartoonists can find themselves in danger. Often they have been described as “canaries in the coal mine”, meaning if you live in a country where cartoonists can lampoon the government without interruption, you may rest assured of your good fortune to live in a (relatively) healthy democracy. If they have been censured then that may be taken as the first symptom of a deeper problem. Such was the case with Turkey, its leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan and celebrated cartoonist Musa Kart.

Kart’s woes began in 2005 when then Prime Minister Erdogan sued him and the Cumhuriyet newspaper over a 2004 cartoon that depicted the politician as a kitten ensnared in a ball of wool. The complaint of “public humiliation” was upheld and minor financial damages awarded. However the Supreme Court later overturned the decision, sending the case back to the lower court, where it was dismissed.

In 2014, following Erdogan’s notorious appearance as a giant hologram at a public event, Kart penned another cartoon that showed him as an insubstantial figure turning a blind eye to malfeasance. Erdoğan took him to court the following year, this time seeking a nine-year sentence for “insulting [him] though publication and slander”. The case had barely gone to trial when it fell apart, and judges dismissed it. Kart had gotten away with it again.

Cartoonists around the world took to their drawing boards in solidarity and the hashtag #caricatureerdogan trended on social media, perhaps sowing the seeds of the Turkish leader’s seemingly permanent dispute with Twitter.

In the ensuing period the crackdown against those accused of insulting the president and causing offence broadened out to an industrial scale. It has been widely reported that at one point nearly 2,000 individual complaints against writers, comedians, journalists, cartoonists, poets and others were being investigated. Even foreign governments such as those of Germany and the Netherlands were pressured to co-operate.

Then came the summer of 2016, an attempted coup and, in its aftermath, a supposed gesture of supreme magnanimity. President Erdogan said: “For one time only, I will be forgiving and withdrawing all cases against the many disrespects and insults that have been levelled against me. I feel that if we do not make use of this opportunity correctly, then it will give people the right to hold us by the throat. So I feel that all fractions of society, politicians first and foremost, will behave accordingly with this new reality, this new sensitive situation before us.”

What the president meant by correct use of the opportunity turned out to be a dangerous slide towards authoritarianism. Many in Turkey saw the coup being used as a pretext to conflate principled opposition with treason. In the massive crackdown that followed, 47,000 people have been remanded in prison and more than 100,000 public sector employees have been summarily dismissed from their posts. Among those whose experiences have been likened to a ‘civil death’ are academics, teachers, judges, prosecutors, local government officials, police officers and army personnel. Journalists and media workers were not spared: more than 120 from all sections of dissenting media are in prison, some so far for eight months, pending their trial on some of the most serious charges under vague anti-terrorism laws. In fact, it is estimated that of all the journalists in prison around the world, a third are jailed in Turkey.

Among them are Musa Kart and 10 of his Cumhuriyet colleagues. After a police raid on his home on Oct.31, 2016 he reported to a police station and was taken into custody. He and his colleagues were held without charge for over five months. Finally, on April 4, only days before the Turkish people narrowly voted in a referendum in favour of giving President Erdogan even more sweeping powers, the government’s lawyers levelled charges of “abusing trust” and “helping an armed terrorist organisation without being a member”, carrying a sentence of up to 29 years in prison. The 306-page indictment contains no solid evidence of these charges. The first hearing in the case is set on July 24, by which time Musa Kart and his colleagues would have spent almost nine months in prison, a punishment in and of itself.

Musa Kart is far from being the only cartoonist, newspaper staffer, or government critic to have been victimized. But his story makes for a clear and instructive case study since, before the current crackdown, President Erdogan tried and failed, time and again, to silence him over the course of a decade.

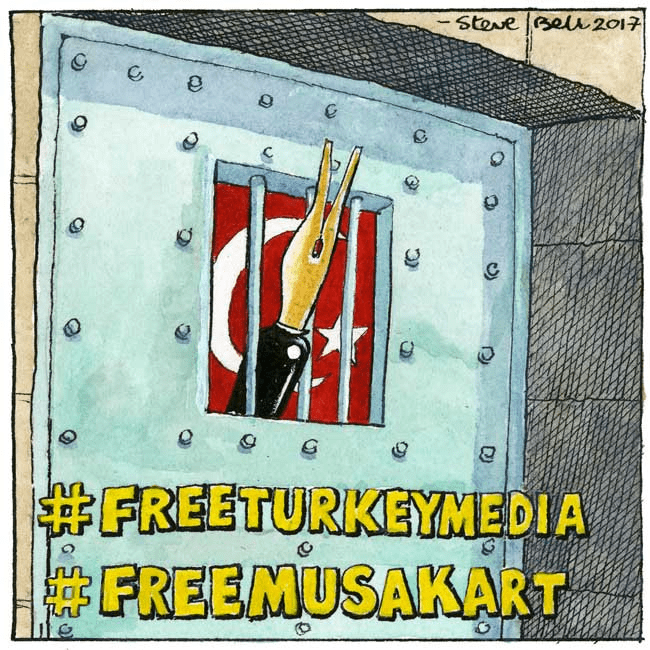

The great irony of cartooning is that the business of taking politics less seriously can result in such grave consequences for the practitioner. Cartoonists tend to resist the suggestion that they are in any way heroic but there is no denying the bravery of colleagues like Musa Kart. His troubles have inspired other cartoonists before and did so again this year, with cartoons both poignant and angry flooding in to the #FreeTurkeyMedia campaign organized by Amnesty International.

On World Press Freedom Day we should remember and honour Musa Kart, a genteel, professional cartoonist whose work indicates an even-handed satirical attitude. He is a reliable scrutineer of Turkey’s government and as such a trustworthy friend to its people. We call for his immediate release and that of all journalists jailed in Turkey simply for doing their jobs.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com