Jon Ossoff doesn’t want to talk about Donald Trump, the Democratic Party or The National Turmoil that has lifted the 30-year-old candidate to the top of the polls in the upcoming special election in Georgia’s

Sixth Congressional District. But as he crisscrossed the affluent north Atlanta suburbs one afternoon in early April, the lanky Democrat paused to ponder how a sleepy off-year race to replace Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price had turned into a national referendum on the President’s tenure. “I don’t know if it’s a blessing or a curse,” Ossoff said with a shrug, sitting on a white leather couch in the back of an office-park studio after taping an interview with a local Vietnamese-American television program. “National political strategy is not something I have time to think about.”

Yet there is little question why the rookie candidate suddenly has a shot to turn this patch of the South blue for the first time in nearly four decades. Since January, the anti-Trump resistance movement has pumped a staggering $8.3 million into Ossoff’s campaign, more than five times the average sum collected by winning House candidates in recent two-year election cycles, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Some 95% of that haul came from out of state, as did Ossoff’s field director, an alumna of Hillary Clinton’s campaign, and some of his battalions of eager volunteers. Polls suggest he’s lapping a field of 11 Republicans and five Democrats, inching toward the majority he needs to win the April 18 election outright and sidestep a June runoff. Ossoff, says former Republican House Speaker Newt Gingrich, who represented this district for 20 years, “is today the national left’s great hope.”

He may also be a glimpse of the Democratic Party’s future. Out of the ashes of Trump’s election triumph has risen a grassroots network dedicated to restocking the depleted Democratic talent pool. A constellation of loosely connected organizations, operating outside the party structure, have taken it upon themselves to draft first-time hopefuls and school them in campaign mechanics, supplying everything from seed money to sample canvassing scripts to volunteers who can proofread press releases over Slack. “These new insurgent organizations are the future of the party,” says Ravi Gupta, a former campaign staffer for Barack Obama who co-founded a group called the Arena that supports new civic leaders and has commitments from more than 400 progressive activists to run for state and local offices.

The resurgent left takes many forms. A single group called Run for Something, which launched on Inauguration Day with a mission to recruit millennials to run for office, already has 30 candidates on ballots in races ranging from seats on state legislatures to city councils, and hopes that number will grow to at least 50 by November. Flippable, which raises money for state legislative races, and the Sister District Project, which helps activists from liberal enclaves connect with competitive contests elsewhere, teamed up to funnel $145,000 to Delaware state senate candidate Stephanie Hansen, whose victory in a February special election preserved Democrats’ control of the chamber. There are other groups devoted to flipping the House in 2018 (like Swing Left), and even one focused on recruiting scientists, mathematicians and engineers (314 Action, named after the first digits of pi). Money is following. In the first quarter of 2017, ActBlue, a progressive fundraising site used by many candidates, raised $112 million, up from $17 million in the first quarter of 2013, after the last presidential contest.

This is the new phase in the national pushback to Trump’s election. The jagged outrage that filled the Washington Mall for the Women’s March and jammed Capitol Hill switchboards in opposition to the President’s Cabinet picks is now being channeled into concrete campaigns to groom a new generation of Democrats. “If we want to see change, the best way we can make it is to run for office,” says Heather Ward, a 21-year-old senior at Villanova University who is running for a school board seat near Philadelphia. “Making phone calls to Representatives is great. But it’s the people in those offices who make the decisions.”

Some Republican strategists worry that they have seen how this sort of activism can end. In 2009 and 2010, a small-government uprising against a new President propelled the GOP back into the House majority and bred a new crop of conservative stars. “It’s almost like the beginning of the Tea Party movement times two,” says Chip Lake, a Georgia GOP strategist who worked for Price and says Ossoff’s strength foreshadows trouble for his party in the 2018 midterms. “It’s a big deal. Clearly we should be pulling the fire alarm.”

It wasn’t long ago that the opposite was true. On the morning of Nov. 9, Democrats awoke to Republican control of the White House, both chambers of Congress, 33 governorships and 69 of 99 state legislative chambers. The roster of party leaders are a rather geriatric bunch. Of the most prominent figures who might consider running for President in 2020–former Vice President Joe Biden, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren and Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders–the youngest is Warren, now 67. Each of the four highest-ranking Senate Democrats is 66 or older, and the trio leading the House are all at least 75. “It’s hard to disagree with the premise that the bench is weak,” says Amanda Litman, a former Clinton campaign official who co-founded Run for Something.

With few exceptions, most Democratic activists who went into politics over the past decade have since gone elsewhere for work, choosing lucrative jobs over the drudgery of electoral politics. “They know politics well enough to know how crappy it is,” explains Gupta. “The idea that you would spend seven days a week raising money, give up a great life so you can have billionaires run ads attacking you in your hometown and, if you win, spend your time in D.C. with sociopaths? It’s understandable that people weren’t deciding to run.”

On his way out the door, Obama tried to address the problem. At his farewell speech in Chicago on Jan. 10, the former President made a plea to his young supporters. “If you’re disappointed by your elected officials,” he said, “grab a clipboard, get some signatures and run for office yourself.”

Ronnie Cho was in the crowd that night, and the line struck a chord. He was an original Obama acolyte, crisscrossing the Iowa cornfields in 2007 as a caucus organizer on his campaign and later following the President to the White House. So at age 34, he decided to leave his job as a vice president for MTV in New York City to run for an open city council seat in his East Village neighborhood this fall. He’s not the only Obama alumnus looking to jump into the ring this year. “I think many of us,” he says, “are eager to give it a shot.”

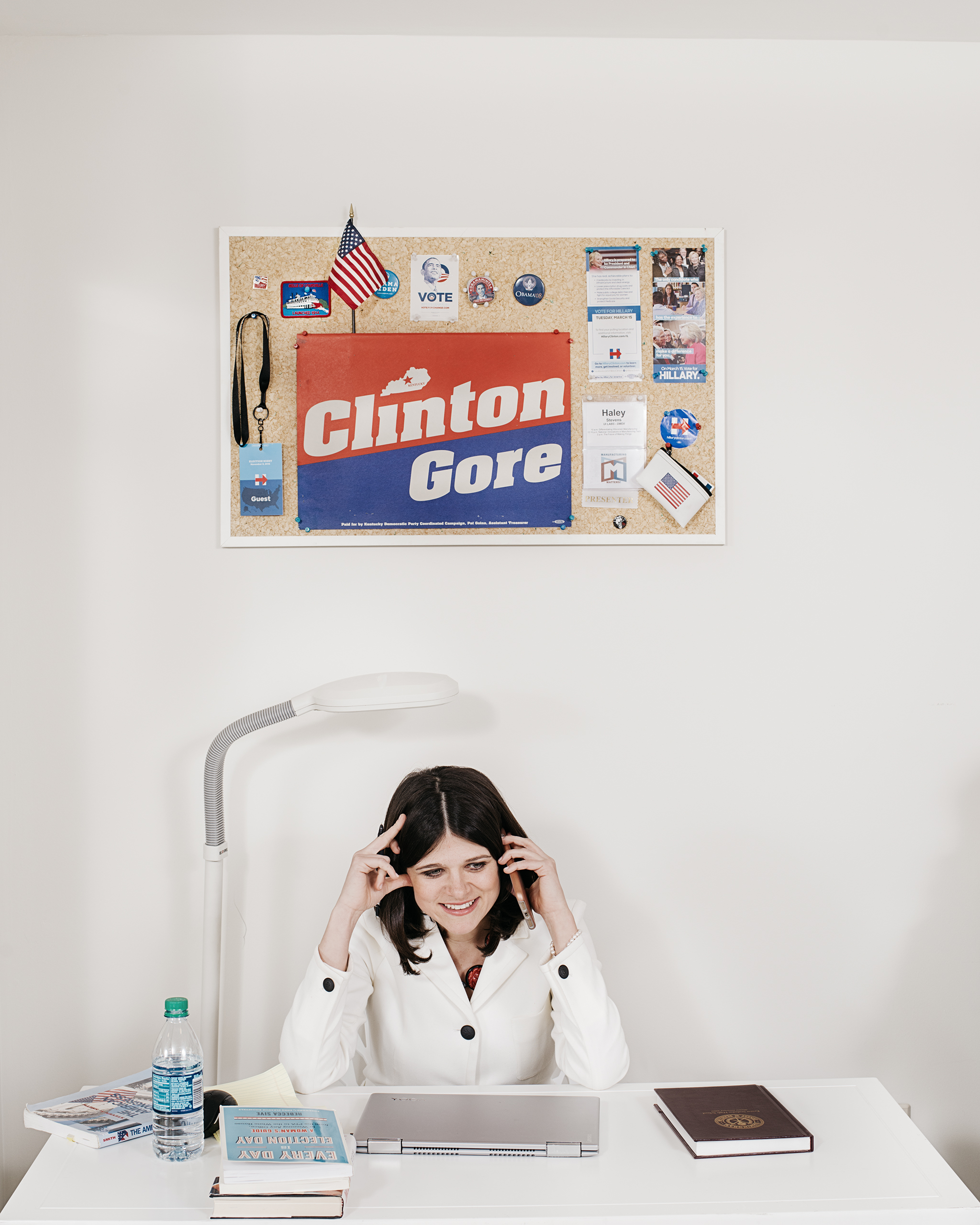

Alejandra Campoverdi, another former Obama campaign aide turned White House staffer, ran in an April 4 special election for a House seat in Los Angeles County. (She lost.) Haley Stevens, a 2008 Clinton and Obama campaign aide who went on to work in the Treasury Department, is leaving her job as a digital manufacturing executive to explore a campaign for Congress in her native Michigan. “It’s not like I’ve been planning some political run,” says Stevens, 33, who began mulling a bid for the Detroit-area seat on election night as she watched the dismal returns trickle in with Clinton’s team at the Javits Center in New York City. “I’m inspired,” she adds, “and I don’t think I’m an anomaly. There are a lot of people who are energized.”

Many of these first-time candidates are completely new to politics. Of the 700 or so hopefuls that Run for Something has screened, even the most seasoned ones needed some help with the rudiments of setting up campaigns. Ward, the school-board candidate in Pennsylvania, got assistance with navigating ballot access; advice from a former Obama and Clinton field organizer on best practices when canvassing (one lesson: always leave campaign literature behind); and feedback on how to hone her pitch. Hannah Risheq, a 25-year-old social worker from northern Virginia who’s running for a seat in the state’s house of delegates, got hooked up by the group with a mentor and a campaign manager. “I thought I’d run in the future,” Risheq says. “I decided: Why not now?”

Jerred McKee, 25, is thinking about running for the city commission in Manhattan, Kans. He wants to help solve the college town’s affordable-housing crunch, so Run for Something connected him with Michael Schmidt, a former Clinton economic adviser who offered a policy tutorial. “The first time I ran, I really felt like I was alone in a lot of ways,” says McKee, 25, who mounted an unsuccessful bid for the same post in 2015. “This provides a network that is extremely powerful.”

Political neophytes like McKee almost never receive institutional support from their party. The reason is simple: backing a rookie is almost always a losing bet. Even the presidency is littered with first-time failures. Before Trump, the last four men to occupy the Oval Office, from Obama to George H.W. Bush, all lost their maiden congressional campaigns. But Democrats have failed to keep pace with Republicans when it comes to nurturing a pipeline of new candidates. “I don’t know why the Democratic Party is not very good at this,” says Lala Wu, a San Francisco lawyer who joined forces with three other Bay Area attorneys to help launch Sister District. “We’re not sitting around twiddling our thumbs, waiting for them to figure it out.”

Some aspiring candidates say the party still hasn’t gotten up to speed. Lindsey Keenan, a corporate lawyer in New York City, would like to run for Congress in her native southeast Pennsylvania. A friend put Keenan, 32, in touch with a Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee official, who promised that a colleague would be in touch. She says it took two months for the committee to follow up. “We have no bench,” Keenan says. “Why would they not want to be supportive?”

That’s where the new progressive network comes in. For now, enthusiasm trumps ideology: unlike the Tea Party, whose goal was to elect doctrinaire conservatives, the new liberal groups are leery of imposing litmus tests on candidates. “We won’t serve as the ‘purity police,'” Run for Something’s online manifesto declares. Swing Left, the group dedicated to retaking the House, says it won’t take sides in Democratic primaries for open seats. Whether it can maintain that posture in a party where the center of gravity is rapidly shifting left is another matter.

On the ground in north Atlanta, everything murmurs momentum for Ossoff: the blue yard signs spreading like kudzu, the early-voting advantage, even the sudden, frenzied onslaught of GOP attack ads. On a Tuesday night in early April, more than 100 people crammed into a spacious suburban house to meet the candidate. As Ossoff entered the foyer and started shaking hands, a pair of teenage girls literally quivered with excitement. “We’ve seen the Democratic Party fall out of power and wander in the desert for so many years now,” says Steve Berman, a commercial real estate broker and local party fundraiser. “Then came Jon Ossoff, who said we don’t have to wait.”

Ossoff is an unlikely prophet. It’s not only that he was producing documentary films just a few months ago. It’s that his smooth pitch to voters doesn’t match the angry mood of the national movement that fueled his rise. He favors buttoned-up suits and burgundy ties and speaks in the blandishments common to Capitol Hill, where he was once a congressional aide. “I will be at your service, and I will make sure your voice rings out in the halls of Congress,” the candidate assured the packed house party. Ossoff first became a Democratic darling with a campaign pitch to “Make Trump Furious.” Now that Election Day is in sight, his goal seems to be to avoid offending anyone at all.

Ossoff’s stump speech is laden with lines about local economic prosperity and “shared values,” as well as stock promises to hold Washington accountable. And while one can intuit his politics–he pulled in $1.35 million from readers of the left-wing Daily Kos, after all–you might mistake him for a Republican on the basis of his campaign ads, which eschew mention of partisan allegiance in favor of promises to work across party lines, fix Obamacare and eliminate government waste. Ossoff worked for Representative Hank Johnson, an Atlanta-area Democrat, and jumped into the race with the endorsement of another Georgia Representative, civil rights icon John Lewis. But he won’t say which other Democratic members of Congress he admires and evades reporters’ questions about the party’s direction. “There are many in this community who are concerned that this Administration may act recklessly, that it is dishonest, that it is not competent,” he says in an interview. “I share all of those concerns. But that’s not what this campaign is about.”

Striving for crossover appeal is a sound strategy. Price carried the district in November 2016 by 23 points, a landslide that was the slimmest of his seven consecutive victories. The army of Republican candidates in the race is chopping up the conservative vote for now, but if Ossoff can’t crack 50% on April 18, he may have a hard time winning a one-on-one runoff in June against a single GOP opponent. In next year’s midterm elections, few Democrats will have the benefit of a fractured GOP field or national attention. But there is no question that the base is motivated. On April 11, a Democratic congressional candidate running in a special election in Kansas with little institutional support lost by just seven points. Trump won the district in November by 27.

To stave off an upset in Georgia, Republicans have launched a multimillion-dollar campaign to kneecap the young Democrat. They’re attacking everything from his address (Ossoff lives just outside the district with his longtime girlfriend, a medical student at Emory University) to the validity of his national-security credentials to his inexperience (one ad features footage of Ossoff as a college student, dressed in a Star Wars costume).”If you get $10 million for a House race, you can look real good for a while,” says Gingrich. “If he doesn’t win outright on the first round, he will lose.”

But the district’s demographics are changing. This enclave of leafy subdivisions and bustling malls is white, wealthy and well-educated, with swelling pockets of Asian and Hispanic voters and a growing community of transplants drawn to the strong job market. Trump eked out a 1-point victory here despite scant effort from the Clinton campaign. “It’s a moderate, pragmatic area,” Ossoff says, “with folks who do not identify as partisans.”

Under pouring rain one April afternoon, Ossoff arrived to speak at Oglethorpe University, a liberal-arts school in suburban Atlanta. Inside a game room piled with pizza and campaign signs, a few dozen college Democrats listened intently as he talked about turning metro Atlanta into a Silicon Valley of the South and steered questions about the party’s national direction back toward local terrain. When he was done, a 23-year-old supporter named Ruwa Romman tried to sum up the excitement.

“Before 2017, there weren’t young Democrats. It was a bunch of old people,” she explains. “I hope that he’s part of a growing phenomenon.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Alex Altman / Atlanta at alex_altman@timemagazine.com