The Senate confirmation of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court of the United States, which was made official on Friday, caps a long and contentious process that began more than a year ago, with the February 2016 death of Antonin Scalia.

But, though this has been one of the longest periods in Supreme Court history with a vacant seat on the bench — and the longest overall since the court went to its current nine-justice format in 1869 — the events that set Gorsuch on his way there can be traced back even further. In some ways, his road to the Supreme Court goes back decades.

Gorsuch’s nomination might not have happened in the first place if the Senate had not refused to consider confirming Merrick Garland, who was nominated to fill that same seat by President Obama. And his nomination would not have been successful this week had Senate Republicans not decided to trigger the so-called nuclear option, which allowed a simple majority to put him on the bench after Senate Democrats not decided to take the extremely rare step of mounting a judicial filibuster.

In short, two factors cleared the way for Gorsuch to succeed: the modern confirmation process, and increased partisanship over judicial nominations that has gone along with it.

Had the situation with Merrick Garland happened in, say, the early 19th century, it wouldn’t have been all that surprising: at the time, as the Pew Research Center has pointed out in its look at long Supreme Court vacancies, the longest-ever opening (841 days) was partly the result of the Senate’s refusal to do anything to move ahead with several of President John Tyler’s nominees to fill the spot. However, at that point, Supreme Court nominations and confirmations didn’t involve the kind of hearings that are seen today. As historian Scot Powe has explained to NPR, the first confirmation hearing for a Supreme Court justice took place in 1916, over the nomination of Louis Brandeis to the court. Prior to that point, the Senate would simply vote yes or no.

Early hearings didn’t actually involve the nominee answering questions; rather, advocates or detractors might make their cases for the candidate. In 1939, however, when Felix Frankfurter was nominated, some of those detractors went so far as to make the case that he should not be confirmed because he was, as TIME summed up their arguments, “a Red, a Jew, an alien.” (Frankfurter was Jewish and born in Vienna, and his enemies tried to paint his involvement with the ACLU as support of communism.) To respond, Frankfurter accepted the opportunity to appear in person before the Senate Committee, at which point TIME reported that “[with] some acerbity he questioned the propriety of Senators publicly examining a nominee for the nation’s highest court.”

That sentiment was key: deference to the Supreme Court as an institution kept people on fairly good behavior, or at least good enough to maintain the idea that deference was normal. Even after Frankfurter and those who followed eventually set the precedent for the nominee coming before a Senate committee to answer questions, the questions were usually not like the ones that are seen today, often focused on judicial philosophy. Rather, they focused, at least in theory, on whether the nominee was qualified for the job.

Things began to change as the 20th century progressed, with battles over Supreme Court seats becoming more contentious and party-oriented, for example when the 1969 defeat of Nixon nominee Clement Haynsworth was seen as a test of party loyalty.

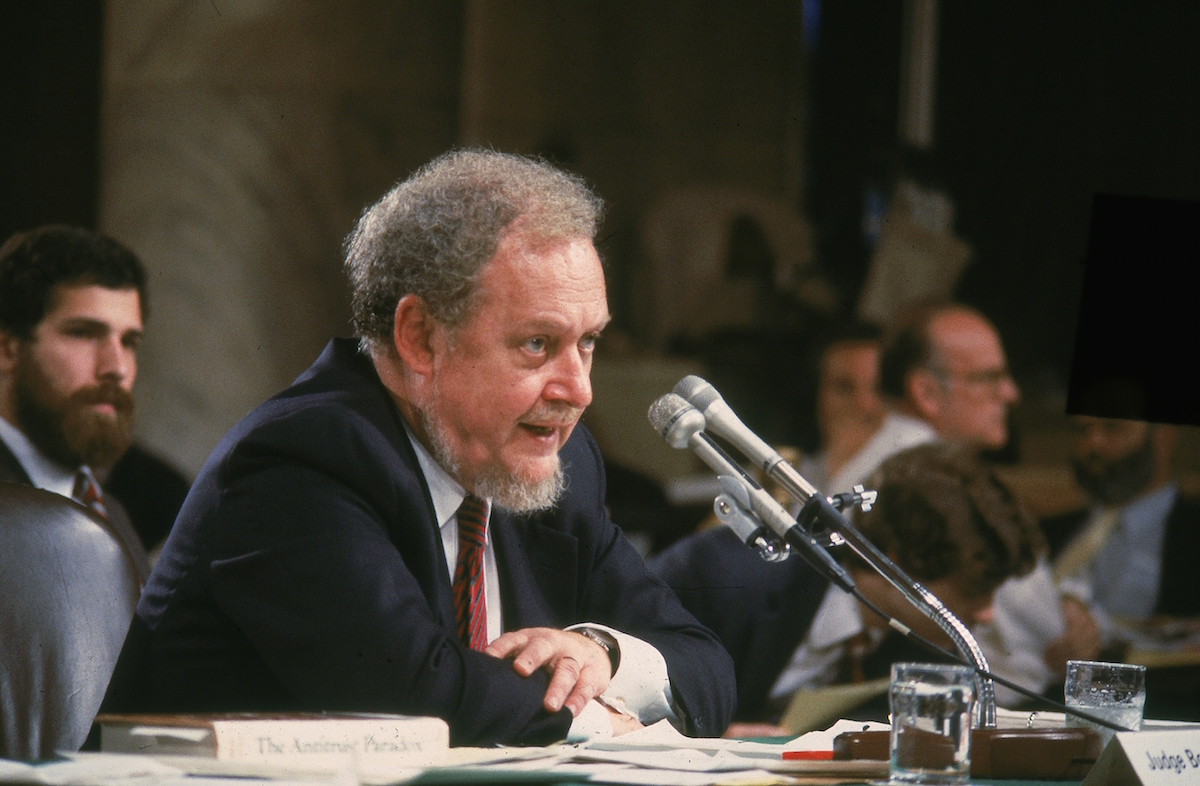

Then in 1987, with Ronald Reagan in the White House, swing justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. stepped down from his seat and Robert Bork was nominated to fill it. At the time, the Democratic majority in the Senate meant that Bork would need to win over not only the conservatives who naturally favored his nomination but also Senators on the other side of the aisle. And for them, the stakes were unusually high: of the four justices left on the court who often supported their views, three had had recent health scares.

Opponents to his getting the seat quickly realized that it would be very difficult to make an argument that Bork, who had who first come to national attention in the 1970s for his role in Nixon’s Saturday Night Massacre, should not be confirmed if the criteria were limited to his qualifications. Those who knew Watergate in and out tended to agree that his decision to comply with the President’s wishes in that case weren’t necessarily a strike against him, and his career record included everything one might hope for in terms of legal expertise and time on the bench. As as result of those factors and the extreme desire to prevent President Reagan from successfully appointing the conservative justice, his confirmation hearing took a new turn.

TIME summed up how the Bork battle was different:

In recent times the Senate’s scrutiny of presidential court appointees has been limited chiefly to questions of their legal ability and ethical fitness. Last week, however, Bork’s opponents in the Democrat-controlled Senate were moving toward a frank confrontation over ideology. Michigan Democrat Carl Levin is talking the language of senatorial prerogative when he says, ”The President has a right to look for a strict constructionist; the Senate has a right to look for a fair constructionist.”

”This battle won’t involve smoking guns or skeletons,” says Nan Aron of Alliance for Justice, a public-interest law group. ”It’s going to come down to philosophy.”

Not everyone agreed that the Senate judging a justice on his views was a good idea. As one TIME reader argued in a letter to the editor, the American people have only one way of influencing the direction of the Supreme Court, which is by electing a President who will pick someone whose ideas they like, and the Senate shouldn’t get in the way of that.

But, for better or worse, a new precedent had been set. That fall, after Bork made the decision to stay in contention for the seat in the face of what looked like sure defeat, the Senate voted 58-42 against his confirmation, which TIME noted the following week was the “largest negative vote in history for a Supreme Court nominee.”

Though Bork was not the first nominee to face tough personal and philosophical questions, his name came to be synonymous with partisan grilling and he helped create a new norm for the process of judicial confirmation.

Bork’s hearings — which were seen by the public in a way that early Supreme Court votes were not — are still seen by many as the turning point for modern public partisan fighting over Supreme Court seats. That shift cleared the way for the many steps that got Gorsuch to his confirmation, from the decision not to vote on Garland to the filibuster and subsequent use of the nuclear option. So, 30 years later, Bork’s rejection has, in some ways, led to a confirmation.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com