Before Mexican photographer Pablo López Luz started shooting aerial photography of the border between Mexico and the United States, there was no President Trump. Talk of building a wall to further divide the two nations hadn’t yet surfaced as a hot button issue in the U.S. Presidential election. By the time Donald Trump announced his candidacy in June 2015, López Luz’s latest art book project, Frontera (Newwer Editorial/Toluca Editions; November 2016), was nearly complete and is now a very timely subject in the wake of the new White House administration.

“I thought it was absolutely impossible that he would be elected America’s next president, and a part of me even thought, ‘Well, this might be interesting if he actually wins, because then my project Frontera would seem even more politically relevant to the bigoted nonsense he was shouting about Mexico and Mexicans,” López Luz told Travel + Leisure.

López Luz’s study of the Mexico-U.S. border does not tell the story of illegal immigration, drug and human trafficking, narco-wars, economic disparity, sex tourism, and all the other problems that have made the border an issue. Instead he focused his lens on the aggregate disparity of both countries as a result of the man-made terrestrial division. He says he wanted to know that if there were no human borders, would those conflicts even exist? For Frontera, López Luz wrote that he wanted to look at the naïve need for order that he says borders falsely provide and that paradoxically become the root of pervasive disorder.

He began photographing the border in 2014 thanks to some initial funding from one of his private collectors. But aerial landscape photography requires good weather. The first time López Luz went up to shoot, it was cloudy the whole flight and they flew to the part of the Rio Grande that he ultimately didn’t find interesting. He had miscalculated. After the six-hour journey, the helicopter touched down back in Monterrey and he had nothing to show from it. Instead of using a digital camera, López Luz shoots with film, which becomes tricky if there isn’t enough light. When he developed the film and saw the contact sheets, he says the images were dark and unusable.

He went on three more flights to shoot the border, though on these occasions it was self-funded. He found a company in San Diego that charged him $600 per hour for the flights. Just after take off, bad weather forced them to land in Tucson, Arizona, where they were grounded for two days. López Luz says that his best aerial shots were taken during a later flight that zig-zagged from Tijuana to Ciudad Juarez then on to El Paso, and back along the border to San Diego. It was the longest flight he had taken and for once, the weather was mostly agreeable. He was able to photograph the border in its entirety, and all the fences and rivers and check points and cities that cleave the U.S. from Mexico.

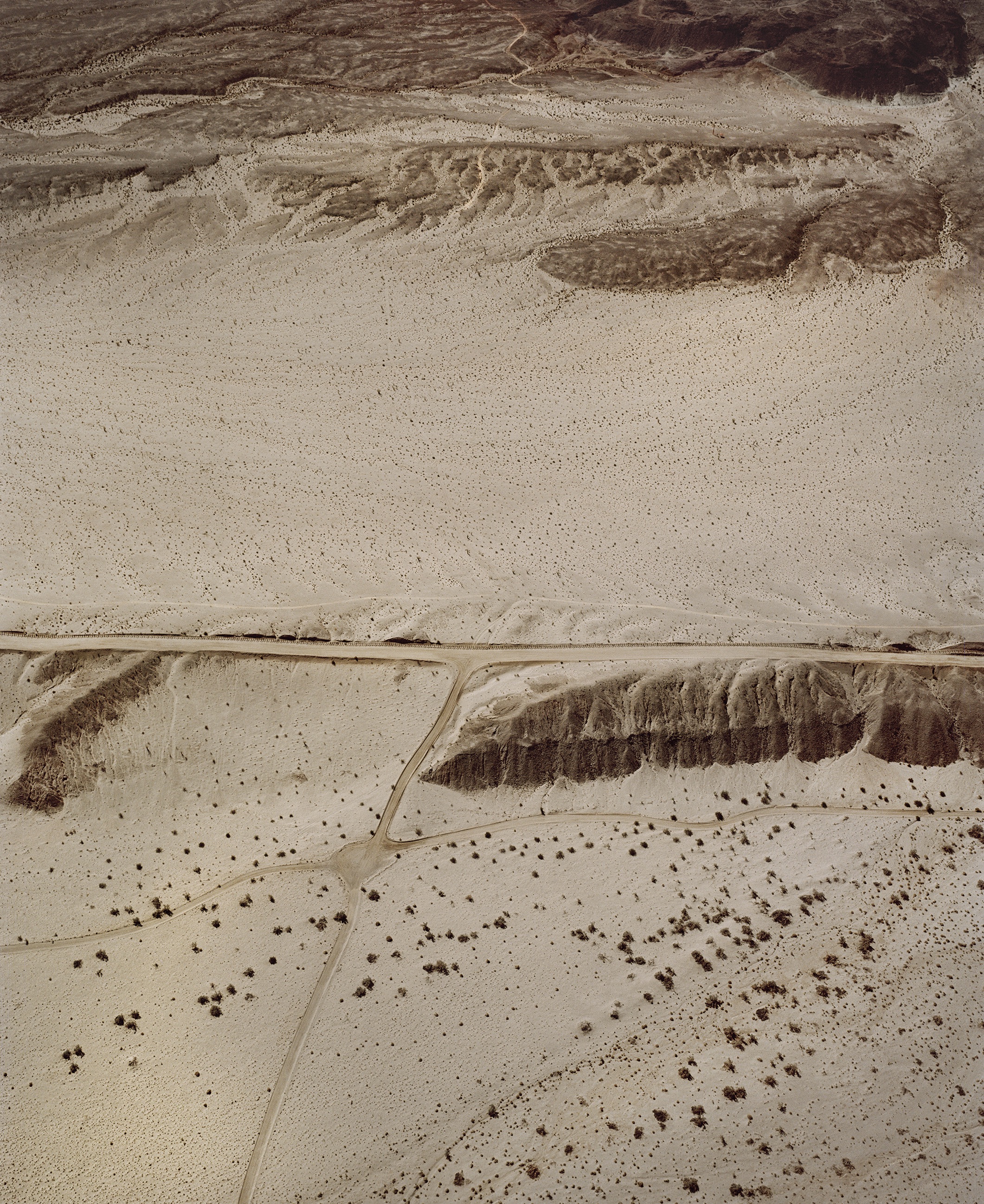

Mexico’s sprawling border cities appear in his photographs as though they’re just inches from spilling over into to the United States. He says this is the only way to distinguish whether you are looking at landscapes belonging to north or south. Mountains, deserts, dry lands, most rivers and all the scrub brush in between—both landscapes blur and appear the same. And that’s what López Luz does; he draws attention to the physicality of the landscape itself—not the disparities that fall on either side of the political boundary.

Moving on from Frontera to face the new political realities taking shape on both sides of the border, López Luz can’t help but question the purpose of a wall nor understand, if built, the potential it has to make matters worse. Not to mention the cost of building a nearly 2,000-mile blockade across deserts, over mountains, and through cities.

“I just question the actual idea of the border, and the actual idea of building a bigger, taller, stronger wall. Once you’ve seen both of our countries from above, from my perspective, you realize how absurd it all is.”

This article originally appeared on TravelandLeisure.com

Baja California – Imperial County VI, 2014

What surprised López Luz the most was the symbolic nature of the U.S.-Mexico border. For most of the border terrain there are few miles divided by a wall or fence.

Barret Junction – Tecate, 2014

Flying along the border, López Luz says there are points where it seems to disappear, usually in mountainous regions. Any man-made division vanishes completely, only to begin again when the terrain becomes flat again.

El Paso – Ciudad Juarez I, 2015

The three biggest cities with border crossings are Tijuana, Mexicali and Ciudad Juarez. All three have serious complexities, with Ciudad Juarez being one of the most dangerous.

Tijuana – San Diego County VI, 2014

Along most of the border, there are few roads or highways near it, save for a few dirt roads that run parallel to it that are used by the U.S. Border Patrol.

San Diego – Tijuana XI, 2015

What attracted López Luz to this project was imagining a landscape bisected by a line, an arbitrary stroke holding such great significance.

Tijuana – San Diego County III, 2014

The photographs of this project were shot during the winter of 2014 and summer of 2015. Four different flights were conducted covering a total of 1,294 miles.

San Diego County – Tijuana IX, 2015

López Luz says that when many people view his photos of the border, they say they can not differentiate which side of the border is the U.S. and which is Mexico.

San Diego County -Tijuana XII, 2015

Tijuana is the beginning of the nearly 2,000 mile-long border.

San Isidro Border Crossing II, 2015

Nearly 14 million cars cross over the San Isidro border annually. According to the U.S. Border Control, it is the busiest border crossing in the Western Hemisphere.

Calexico – Mexicali II, 2015

López Luz previously worked on a project that included aerial views of dense and polluted landscapes of Mexico City. He again included cities, specifically border-cities in his Frontera project, as they are integral components of border problems.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com