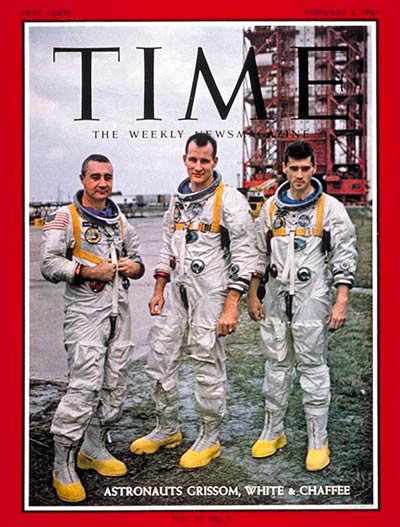

Sudden death is always shocking, and even more so when those who die are heroes who defied danger in the past. But on Jan. 27, 1967, when the U.S. lost its first three astronauts killed in the line of duty — Lieut. Colonel Virgil “Gus” Grissom, 40; Lieut. Colonel Edward White, 36; and Lieut. Commander Roger Chaffee, 31 — the world’s reaction contained an extra level of shock.

The reason why is suggested by the fact that, though the mission on which they were killed is now known as Apollo 1, that phrase never appears in TIME’s original 1967 cover story about the event. The men were not killed during a grand attempt to reach the moon, but rather during what was supposed to be a routine pre-flight test for what was then known as Apollo 204 or AS-2014, so called after the spacecraft in use.

As TIME presented the story, the nation and the world knew that the effort to put a man on the moon was a dangerous one. Every time a brave astronaut took another step forward — orbits or space walks, for example — a collective breath was held, with the awareness that it would be so easy for something to go wrong. Grissom and White themselves were already famous for their death-defying feats. But when Grissom, White and Chaffee died, they were “motionless and earth-bound,” reclining “in the charred cockpit of a vehicle that was built to hit the moon 239,000 miles away, but never got closer than the tip of a Saturn rocket, 218 ft. above Launching Pad 34 at Cape Kennedy.”

Here’s how TIME explained what happened that day:

At 1 p.m. on Friday last week, Grissom, White and Chaffee strolled casually into the gantry elevator on Pad 34, rose swiftly to a sterilized “white room,” then ambled along the 20-ft. catwalk to the stainless-steel hull of the capsule, now secured to the Saturn rocket inside the launching complex. The craft was like an old friend, for they had spent hours in it during vacuum-chamber tests in the Houston Space Center, had run through identical launch-simulation procedures several times before.

All spacecraft have their own personal quirks, and 204 had been balky from the start. As an Apollo engineer said: “The first article from the factory cannot come out without birth pains.” The spacecraft gave repeated trouble. The nozzle of its big engine shattered during one test. The heat shield of the command module split wide open and the ship sank like a stone when it was dropped at high speed into a water tank. Certain kinds of fuel caused ruptures in attitude-control fuel tanks. The cooling system failed, causing a two-month delay for redesign. But all the bugs were eventually ironed out, as far as the experts knew, after arduous testing under every conceivable circumstance. Last week’s test was billed as the ship’s first full “plugs-out” operation—meaning that the craft was to rely solely on its own power system instead of using an exterior source. The trio climbed inside the ship, hooked up their silver suits to the environmental control system (which feeds oxygen to the suits and purifies the air in the cabin), snapped their faceplates shut and waited while the suits became pressurized. At 2:50 p.m., the airtight double hatch plates were sealed. And the familiar routine began, an infinitely detailed run-through that was scheduled to last slightly more than five hours.

Things progressed smoothly enough; a few “glitches” (minor problems) stalled the operation. At countdown-minus-10-minutes, the procedure was stopped again because of static in the communications channels between the spacecraft and technicians at the operations center. It took 15 minutes to correct the problem, and the simulated count was ready to begin again. Then, at 6:31 p.m., a voice cried from inside the capsule: “Fire aboard the space-craft!”

At the same instant, a couple of technicians standing on a level with the craft windows saw a blinding flash inside the ship. Heavy smoke began to seep from the capsule, filling the white room. A workman sprinted across the catwalk leading to the craft, tried desperately to loosen the hatch cover. He was driven back by the intense heat and smoke, but half a dozen other technicians, some wearing face masks and asbestos gloves, raced to help. One or two would try to wrench open the hatch, then fall back from the scorching heat while others struggled with it. Six minutes after the cry of alarm, the hatch sprang open. A blast of hot air shot out, followed by suffocating clouds of smoke.

The rest was silence. The flames were apparently sucked into the astronauts’ space suits, killing them as soon as they noticed the fire. The three charred bodies were left strapped to their couches for more than seven hours while anguished experts sought to piece together the reasons for the accident.

By April, it had been determined that, though it was unlikely that technicians could ever figure out with 100% certainty what had happened, the fire was probably started by a conductor that malfunctioned and “spurted” its electrical current.

Although the routine nature of the test that killed those men could have potentially detracted from their sacrifice, it did just the opposite: they were all-too-human reminders of the danger of space, and of the level of technical ability required of all astronauts. And as such, though some feared that the accident would cause the U.S. to pull back on the effort to make it to the moon, NASA continued to move steadily ahead, confident in the knowledge that Grissom, White and Chaffee, professionals till the end, would have wanted it that way.

“New as it is in the history of mankind’s progress, the conquest of space symbolizes one of man’s oldest, most basic drives: the hunger for knowledge, the lure of every new frontier, the challenge of the impossible,” as TIME noted. “And that is the legacy left behind by Virgil Grissom, Edward White and Roger Chaffee— just as it was by men like Marco Polo, Magellan, Charles A. Lindbergh and Explorer Robert Falcon Scott, whose Antarctic memorial bears an inscription from Tennyson’s Ulysses: ‘To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.’”

And NASA soon took another step forward, too: announcing that the mission for which the three men had been preparing would be known as Apollo 1.

See the full issue, here in the TIME Vault: “To Strive, To Seek, To Find, And Not To Yield…”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com