Theatrics are an integral part of the American presidential inauguration. A well-located stage, many actors, a few scripted roles, costumes, crowds and waving flags all culminating in the oath of office. After the deed was done this time, artillery pieces fired and the new President spoke; cameras whirred and the audience roared.

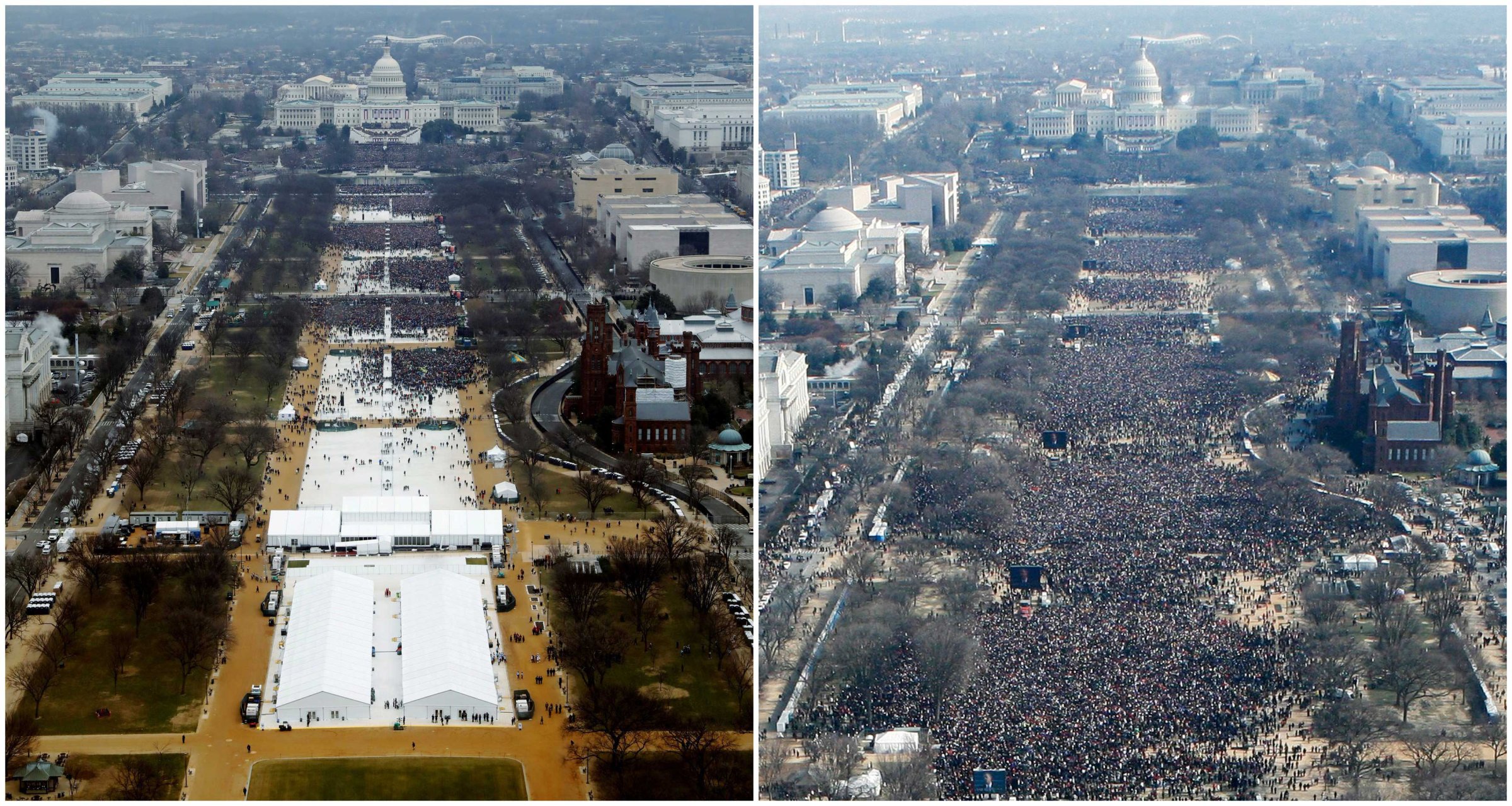

But it was the crowd that soon drew attention. How many people had been there to watch? An image, shot by a Reuters photographer from the top of the Washington Monument, of the crowd in attendance, showed significantly fewer people than at Barack Obama’s inauguration in 2009.

A new White House Press Secretary emerged the next day to vehemently assault the facts about crowd size, his demonstrable falsehoods disproven by those images. Another senior official later said he was deploying “alternative facts” and that we should believe him, despite the photographic proof to the contrary. And yet another official added today that the media should “keep its mouth shut.”

It’s reminiscent of George Orwell’s 1984, when the main character, working in the Ministry of Truth, destroys a politically inconvenient image: “He dropped the photograph into the memory hole, along with some other waste papers. Within another minute, perhaps, it would have crumbled into ashes.”

So, what role is photography to play in this “post-truth” era, when even documentary evidence is denied or disputed by those in power, where access is controlled, where we suffer from an information overload and the battle for the information space is chaotic and fought on a thousand fronts?

Once upon a time we were told that “a photograph never lies” and that we should trust in the still image. Nowadays, drenched in information, much of it visual, we struggle to make sense of the personal and professional views on our world.

From the general public and our friends, we receive (and often redistribute) a stream of family photos, selfies, cute animal pics and sometimes, eyewitness videos of dramatic events. From the professional media, we get (and redistribute) high-quality news, sports, entertainment and feature photography, stories, and videos. And from a host of outlets disguised as news organizations we receive doctored images, conspiracy theories and fake news produced to further an agenda or simply to make money from advertising should it go viral.

Regardless of source, images are plucked out of the traditional and social media streams, quickly screen-grabbed, sometimes altered, posted and reposted extensively online, usually without payment or acknowledgement and often lacking the original contextual information that might help us identify the source, frame our interpretation and add to our understanding.

In addition, as media outlets struggle to survive in the online revolution, they are increasingly catering to the storytelling they believe their audiences want (and might even pay for), perpetuating partisan viewpoints and further confusing those in search of some sort of truth.

Who, then, can we trust? Respected news agencies like the Associated Press and Reuters, among others, go to great lengths to ensure the accuracy of the content they distribute and while mistakes are sometimes made, what they report and show is generally trustworthy.

Regardless, the swollen and treacherous river of content now requires us to question the source of everything we see and read; but for many of us this questioning process is too often absent, or underdeveloped.

Even the notion of the image as an icon, with gravitas and importance, is now precarious. Such pictures occasionally surface (like the drowned Syrian toddler on a Turkish beach) but are quickly swept away and mainly forgotten. Instead we measure an image’s importance not by how long it lasts in our collective memory but rather by how quickly it is disseminated and how many people see it. Did it go viral? One virus leaves us, to be replaced next day by another.

The way photographs are consumed has also changed. Gone, for most people, is the habit of reading an image carefully and absorbing its nuance and detail. Now with so many images, there is little time to absorb each one – or any. Glance, swipe, glance, swipe, often on a tiny smartphone screen. Today’s teenagers consume information on one, two or even three screens simultaneously.

In the midst of this, photojournalism somehow survives, despite having been declared dead by its practitioners several times over recent decades – usually because of assignment cutbacks. While the economics of the news business remain complicated and troubling, all over the world there are still brave and dedicated photojournalists producing amazing and varied imagery.

Photography will continue to be well used in our increasingly visual world, not just by media outlets, but by many non-media actors in order to further their agendas. Of course, those same players will continue to try and control independent journalism, to limit its awkward questions and investigations.

Access for photojournalists to the White House, for example, has long been a contentious topic, with the Obama administration increasingly shutting out the media and releasing sanitized official photographs. With the departure of the photogenic Obama family, the best of those official images – some of them quite compelling – were widely shared and celebrated in the media, with many news outlets choosing to play down their provenance as government hand-outs. That stance does independent journalism a terrible disservice in the long term, normalizing our acceptance of what is essentially propaganda.

The “post-truth” environment we live in seems, at least in part, to be a function of the current confusing information flow and how politicians, governments and others use it towards their own ends. It remains to be seen what longer term effects this will have on journalism generally and photojournalism in particular but the power of the still image remains undeniable, even if some choose to ignore inconvenient truths.

Santiago Lyon, a longtime photojournalist, was, most recently, vice president for photography at the Associated Press.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com