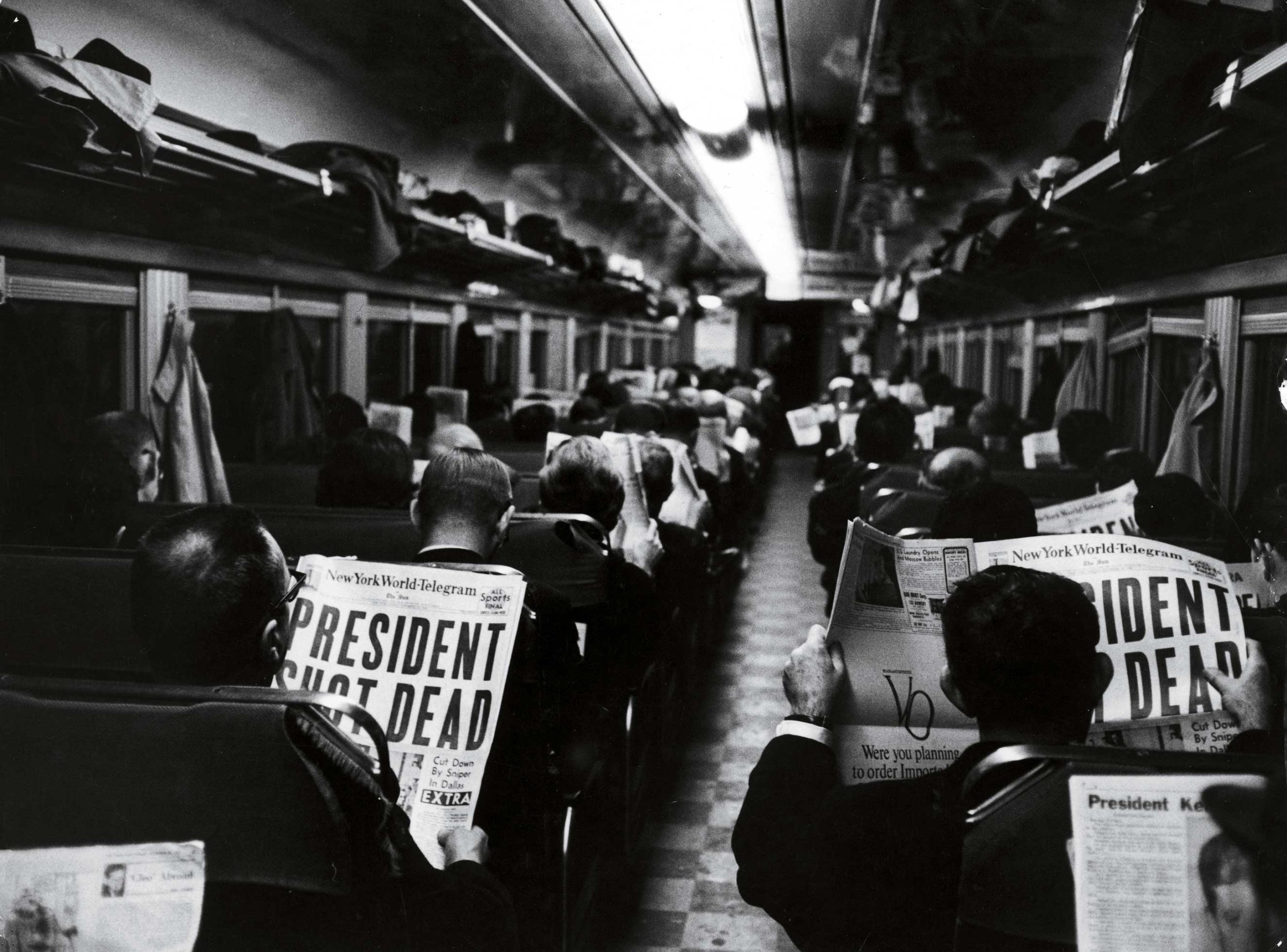

The tortured path that began with a left turn onto Dealey Plaza on Nov. 22, 1963, will find its unlikely end point this October in College Park, Md. At a National Archives annex, the last remaining documents related to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy are being processed, scanned and readied for release.

For those who believe that the clues to who killed JFK are hidden somewhere deep inside the government’s files, this may be the last chance to find the missing pieces. Under the terms of the 1992 JFK Records Act–a result of Oliver Stone’s 1991 movie JFK, which revived fascination with the idea of a cover-up–the government was given 25 years to make public all related files. The time is up on Oct. 26, 2017. About 3,000 never-before-seen documents, along with 34,000 previously redacted files, are scheduled for release.

The files–many of which trace back to the House Select Committee on Assassinations from the 1970s–promise to be less about second shooters and grassy knolls and more about what the government, particularly the CIA, might have known about assassin Lee Harvey Oswald before Kennedy’s death. (The CIA declined to comment for this story, and the FBI did not respond to a request.) Already, the law has helped fill out one of the most significant periods of the 20th century, revealing information on military plots to invade Cuba; Kennedy’s plans to execute a withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam; and the formation of the Warren Commission, which investigated the assassination.

According to the National Archives, the final batch includes information on the CIA’s station in Mexico City, where Oswald showed up weeks before JFK’s death; 400 pages on E. Howard Hunt, the Watergate burglary conspirator who said on his deathbed that he had prior knowledge of the assassination; and testimony from the CIA’s James Angleton, who oversaw intelligence on Oswald. The documents could also provide information on a CIA officer named George Joannides, who directed financial dealings with an anti-Castro group whose members had a public fight with Oswald on the streets of New Orleans in the summer of 1963.

“The records that are out there are going to fill out this picture,” says Jefferson Morley, an author who’s spent decades researching the assassination.

But Martha Murphy, who oversees the effort at the National Archives, warns that many of the documents may be of little value. She believes that any potentially revelatory information, like Oswald’s CIA file, has already been released–albeit with redactions (that text will be restored for the new release). Most of the trove was deemed “not believed relevant” by the independent Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB) in the 1990s. Still, John Tunheim, who chaired the ARRB, says “something that was completely irrelevant in 1998 may look more tantalizing today.”

For curious observers, even irrelevant documents are better than nothing–and nothing is still a possibility. The law says that if an agency doesn’t want certain files made public, it can appeal to the President, who could decide to hold them back after all. That has prompted almost two dozen authors, academics and former ARRB members to write to the White House counsel urging that all documents be released.

“We’re at the final chapter of JFK disclosure,” Morley says. “Sometimes I think we’re going to win. Sometimes I think it’s a fool’s errand. But we’re going to find out.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com