In 2003, I was part of the effort to find Saddam Hussein. I then became the first to debrief him after his capture that December. Prior to his incarceration, I heard over and over from counterparts in the military and the Bush administration that if we caught Saddam we would be able to nip the growing Iraqi insurgency in the bud. This presupposed that Saddam had an iron-like control over the Sunni insurgency (he didn’t) and that decapitating the Baathist regime would make Iraq a peaceful country (it didn’t). This was the underlying ethos of the Bush administration’s decision to launch Operation Iraqi Freedom in March 2003, to remove Saddam from power so that democracy and freedom could flourish in a post-911 Middle East.

When I interrogated Saddam, he told me: “You are going to fail. You are going to find that it is not so easy to govern Iraq.” When I told him I was curious why he felt that way, he replied: “You are going to fail in Iraq because you do not know the language, the history, and you do not understand the Arab mind.”

Unlike Barack Obama, who entered office with Iraq relatively peaceful following the the surge of U.S. troops and the Anbar Awakening, President-elect Donald Trump has monumental decisions to make regarding the Middle East. Iraq—and Syria, too—will be central to U.S. counter-terrorism efforts in the next administration. The new administration will have to compose a revised strategy for dealing with the menace of ISIS, one that comprises a military and a political track. While the Obama administration is making a concerted effort to destroy ISIS militarily, and Iraqi forces—with the help of the United States—have recently made some progress toward that end, we are still far from achieving this goal. However, if security and political stability cannot be achieved in the wake of military victory, the gains that will be made could be short-lived.

Today, a decade following Saddam’s execution, with ISIS’s black flags still unfurled over sections of Iraq, we need to ask ourselves some provocative questions. One of them is: What would have happened if we had just kept Saddam in his box or if the successor Iraqi government had shown mercy and commuted his death sentence to life imprisonment?

It is impossible to say with any certainty. But my own belief is that if Saddam had remained in power, Iraq would have eventually gotten out from under international sanctions—which had already been crumbling by 2001—and he would probably be in charge today, preparing one of his sons to take over after his death. I doubt that he would have had much to worry about from an event like the Arab Spring. Saddam’s leadership style and penchant for brutality were among the many faults of his regime, but he could be ruthlessly decisive when he felt his power base was threatened, and it is far from certain that his regime would have been overthrown by a movement of popular discontent.

Likewise, it is improbable that a group like ISIS would have been able to enjoy the kind of success under his repressive regime that they have had under the Shia-led Baghdad government. Saddam felt that Islamist extremist groups in Iraq posed the biggest threat to his rule and his security apparatus worked assiduously to root out such threats.

Although I found Saddam to be thoroughly unlikeable, I came away with a grudging respect for how he was able to maintain the Iraqi nation as a whole for as long as he did. He told me once, “Before me, there was only bickering and arguing. I ended all that and made people agree!” Saddam used every tool in his repertoire to maintain Iraq’s multi-ethnic state. Such tools included murder, blackmail, imprisonment, threats, and these were to be used to cow his enemies. For his friends, Saddam would dole out patronage to tribal leaders and supporters in the form of cash, elaborate gifts, land, and other largesse that was the lifeblood of an oil rich state. Today’s Iraq has been riven by deepening sectarianism that always seems to be only a step away from igniting again, as it did after Saddam’s overthrow.

Saddam also would have inevitably maintained a hostile stance toward Iran; he was very proud of his opposition to the Islamic Republic and reserved special contempt for the Shia in Iraq who would follow Iran’s guidance over his. Iraq is now very much the junior partner to a much emboldened Iranian regime that has expanded its military and security influence in the chaotic aftermath of Saddam’s overthrow and the aborted Arab Spring.

In December 1992, President-elect Bill Clinton was asked by a New York Times reporter what he intended to do about Saddam and Iraq. Clinton responded casually, “If he wants a different relationship with the United States and with the United Nations, all he has to do is change his behavior.” The ensuing criticism from the national security community reportedly spooked the new president, who had won by a thin margin in a three-way race and who was coming to the office with the thinnest of foreign policy credentials. Subsequently, Clinton never returned to this instinct and, instead, attacked Iraq militarily in 1993 and 1998. Moreover, although he did not know it at the time, Clinton also sealed Saddam’s death warrant when he signed the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998, which made regime change in Iraq the policy of the U.S. government. What might have happened if Clinton would have stuck to his initial instinct and tried to forge a new relationship with Iraq? What might we have avoided in terms of lives, treasure, and prestige wasted in our fruitless effort to re-order the region?

Our incoming president has the opportunity to play a very large role in shaping a new regional order in the Middle East. This will require making tough decisions and, ultimately, recognizing that we may have to deal with people and leaders that we abhor if we want to help bring stability back to the region and limit the scope of terrorism’s reach. Most of all, it will require placing diplomacy back into our foreign policy. President-elect Trump has shown with his election victory that he is a believer in “the art of the deal.” Maybe his administration can use this negotiating skill and end our involvement in the forever war.

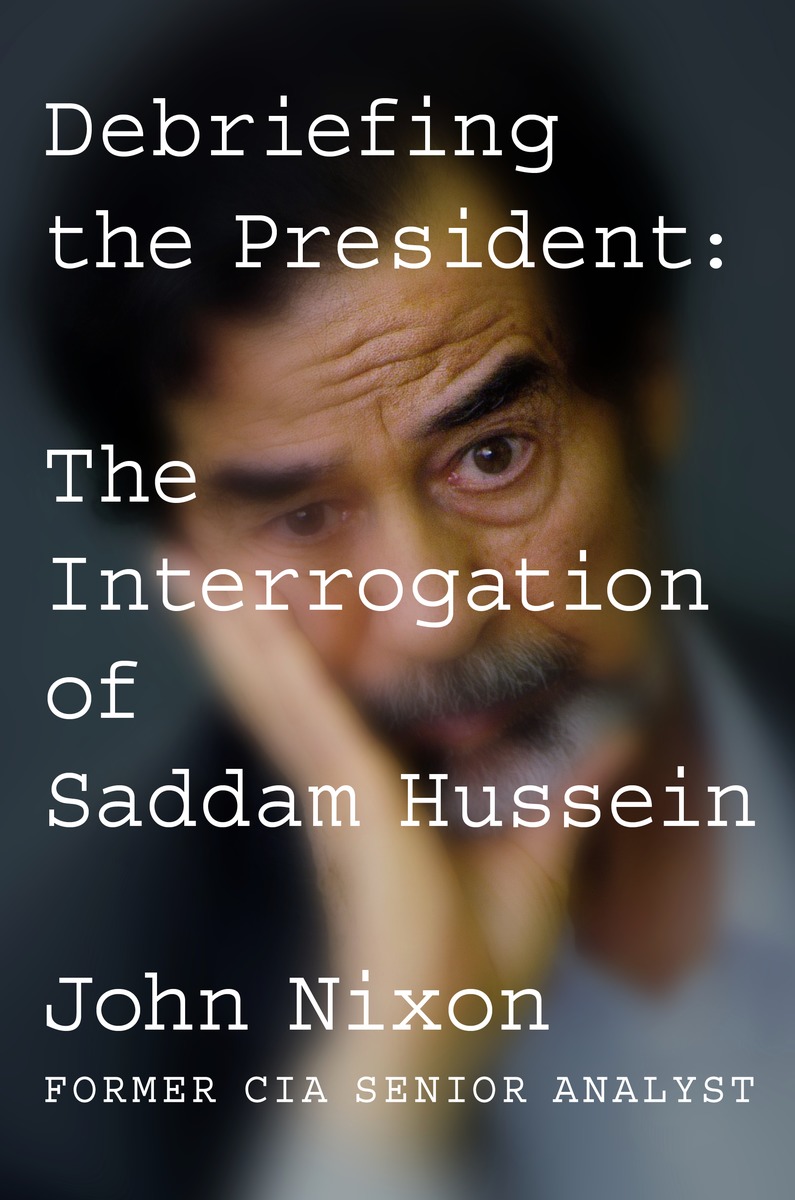

Adapted from Debriefing the President: The Interrogation of Saddam Hussein by John Nixon. Published by arrangement with Blue Rider Press, a member of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2016 by John Nixon.

Nixon was a CIA analyst from 1998 to 2011 and has taught leadership analysis for the agency at its Sherman Kent School; he is the author of the forthcoming book, Debriefing the President: The Interrogation of Saddam Hussein.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com