Brittney Cooper is a black feminist theorist who teaches at Rutgers University and writes a weekly column for Salon.com

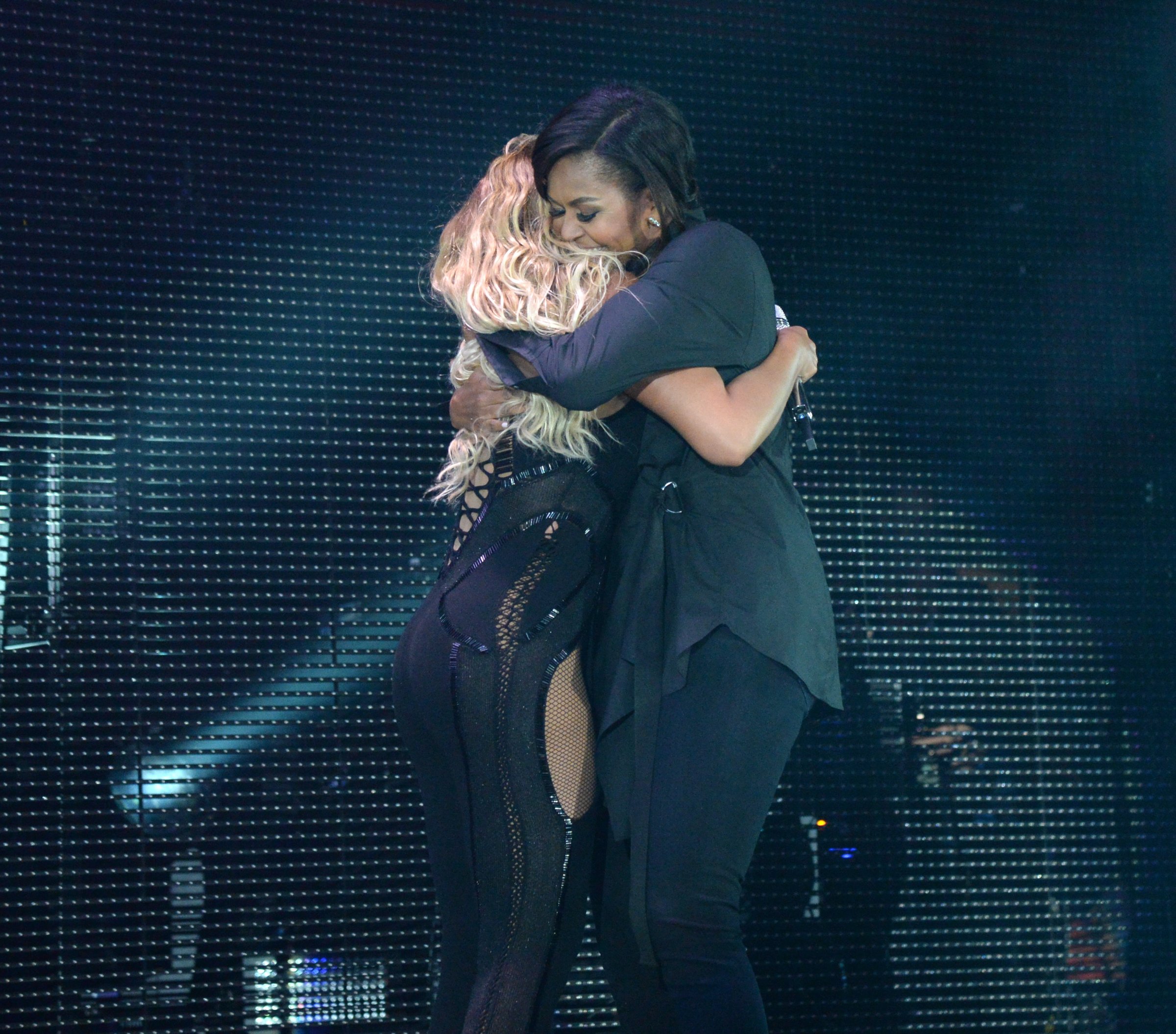

The mutual girl crush that Michelle Obama and Beyoncé share is a serendipitous study in twenty-first-century Black girlhood, womanhood and ladyhood. In 2009, Beyoncé performed Etta James’s classic song “At Last” at one of the inauguration balls for President Obama. Coupled with the President’s professed admiration for Beyoncé’s husband, Jay-Z, it seemed that the Obamas were kind of like the well-heeled, older brother and sister doppelgangers of Hip Hop’s First Couple. Through the President’s two terms, the romance has continued. In 2011, the First Lady partnered with Beyoncé as part of her Let’s Move! campaign to combat childhood obesity. By this point in the President’s first term, Mrs. Obama had made her mark as mom-in-chief, as fashion icon, and as a loving, playful, dancing advocate for the health of the nation’s children.

In many respects, Mrs. Obama epitomizes the triumph of the project of respectability that consumed Black women organizers at the turn of the twentieth century. Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century “race women” had hoped in the words of Harvard historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham that an “emphasis on respectable behavior [would contest] the plethora of negative stereotypes by introducing alternative images of black women.”1 With her Ivy League education, two-parent upbringing, traditional marriage to an Ivy League–educated brother, and two beautiful, well-behaved daughters, Michelle Obama represents more than the race women who occupied the public sphere before her could ever have dreamed. When she declared herself mom-in-chief to the chagrin of many white feminists who felt that she should “lean in,” many Black women celebrated. For once, African American motherhood would be center stage in American politics in a celebratory manner. As mom-in-chief, Michelle Obama could correct decades-long stereotypes of Black women as neglectful parents and money-grubbing welfare queens. Even as these stereotypes persist as an animating force in right-wing policies in the form of ugly dog whistles about “handouts” and “personal responsibility,” a visible and credible counter narrative now exists. In a world in which Black women were always treated as women but never as ladies, a Black woman becoming the icon of American ladyhood is a triumph of the hopes and dreams of all those race ladies of old.

Thus, Michelle Obama’s vocal admiration for pop superstar Beyoncé is nothing if not curious. I’d venture to say that most grown Black women and the girls who will become them someday have an inner Beyoncé. Inner Beyoncé is a sexy chanteuse, whose milkshake brings all the boys to the yard. Inner Beyoncé might have Michelle Obama reminding her hubby Barack that she upgraded him, not the other way around. The curiosity is not that Michelle Obama has an inner Beyoncé; it is rather that this quintessence of twenty-first-century Black ladyhood admits to it.

Once asked who she would be if she could be anyone other than herself, Michelle Obama replied, “Beyoncé.” And Beyoncé has embraced this relationship with mutual admiration and affection. It is Beyoncé who grew up in an upper-middle-class family in Houston, while Michelle Obama grew up a generation earlier in a working-class family on Chicago’s South Side. It is Michelle Obama who took a chance on a lawyer with little money and less professional rank than her, while Beyoncé married the former drug dealer turned rap music mogul Jay-Z. Still, because Beyoncé makes her money through not only her considerable vocal talent but also her consummate beauty and sex appeal, she invokes a different social genealogy of Black womanhood than the one from which Michelle Obama issues. Beyoncé is classed among the Josephine Bakers, the Millie Jacksons, the Ma Raineys and Bessie Smiths. Her connection to these bawdy traditions of blues and soul are remixed in a contemporary R&B and Hip Hop package that frequently makes Black feminists lose their minds, some out of unparalleled pleasure, others out of unparalleled dismay.

Bey knows others objectify her body, and it seems she kind of likes it. In the “Partition” video for her 2013 visual and self-titled album Beyoncé, her actual, unretouched ass is a character in many of the video’s scenes. This kind of self- objectification feels celebratory for some feminists and retrograde and dangerous to others.

Thus, there are risks to Michelle Obama’s choice to align herself with Beyoncé socially. On the one hand, she gets cool points from younger crowds. On the other hand, many Black women might clutch their pearls at Michelle Obama’s embrace of a Black woman who is frequently understood within the mythos of unbridled Black female sexuality. Whereas Beyoncé’s unapologetic focus on her body and sex appeal frequently causes her to be perceived as a threat to children by soccer-mom types who wish she would simply cover up and stop gyrating, many moms love the idea of their children doing a more chaste form of gyration with Michelle Obama for her Let’s Move! campaign.

During the launch of that campaign, Beyoncé remixed her 2006 song and video, “Get Me Bodied,” a bass-driven club anthem, into the child and family-friendly “Move Your Body,” a savvy marketing decision which helped make the campaign seem fun and exciting for children. In this regard, Michelle Obama’s engagement with a pop icon created a context to make her campaign socially relevant and impactful.

But the First Lady has also chosen more risky allegiances with Beyoncé, particularly in her husband’s final term. When Beyoncé performed with Coldplay at the 2016 Super Bowl, the Obamas sat down with Gayle King to discuss their Super Bowl–watching plans. Michelle told Gayle, “I care deeply about the Halftime Show. Deeply. I got dressed for the Halftime Show. I hope Beyoncé likes what I have on.” The First Lady was dressed in a black blouse with black slacks. Several hours later, Beyoncé performed her new hit “Formation,” a song whose video offered an overt critique of anti-Black state violence, while wearing an all-black leather outfit and a makeshift breastplate made of bullets. A salute to the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Black Panther Party, the clear celebration of the Black Power Movement unsettled many white Americans who claimed that Beyoncé and her dancers were anti-police.

But Mrs. Obama’s coy overture in all Black to the impending performance offers perhaps a slight window into her love affair with Beyoncé. During the President’s 2008 campaign, in an infamous cover called “The Politics of Fear,” the New Yorker satirized an iconic campaign fist bump that Michelle gave Barack prior to one of his speeches, by ginning her up in a Black Power–era Afro, and slinging a machine gun around her body, with a strap across her chest made of bullets.

Eight years later, Beyoncé’s Superbowl costume, a clear tribute to the sartorial choices of the Black Panther Party, perhaps unwittingly, invoked this image as well. It was backlash over the image coupled with hand-wringing and vitriol toward Mrs. Obama during the President’s first campaign that caused her to retreat to the safer position of mom-in-chief. Eight years earlier, in February 2008, Michelle Obama said on the campaign trail, “For the first time in my adult lifetime, I’m really proud of my country,” a remark that celebrated Barack’s success in the primaries and America’s ostensible desire to overcome its long history of racial discrimination. Before we knew Michelle Obama as mom-in-chief, we knew her as the well-educated, politically thoughtful, and appropriately critical wife of a young politician with a rising star.

Her unassuming honesty about the ways that racism had challenged her faith in American democracy also betrayed something of the political discontent that many sisters feel with the American political system. Her candor unfortunately situated her within the rhetorical realm of the Angry Black Woman, a shift that is a surefire way to discredit the legitimate claims Black women make about the limitations of American democracy.

In Beyoncé then Michelle Obama has found someone who is not bound by the same expectations of respectability, or rhetorical reticence, or the performance of chaste sexuality that shapes the lives of public Black women. To the extent that people try to police and regulate Beyoncé’s choices in this manner, she takes great pleasure in flouting the rules of social propriety.

Where Michelle Obama’s fist bump and the subsequent satirizing of it fueled the racial panic of white Americans and might conceivably have cost her husband the presidency, Beyoncé could forthrightly invoke this history. Beyoncé’s Super Bowl performance demanded some level of social reckoning with the truth of the Black Power Movement, and its descendant, the current Movement for Black Lives, in ways that Michelle Obama could never do. But Michelle’s quip to Gayle that she hoped “Beyoncé likes what I have on” suggests not only some level of Black girl solidarity, but also the sense that the song “Formation” gave voice to matters that would otherwise go unvoiced for the First Lady.

More than two decades ago, Darlene Clark Hine, a historian of Black women at Northwestern University, wrote about the ways that race women had perfected a culture of dissemblance, a strategy of moving through social space in which Black women gave the appearance of openness, while holding their most private, innermost thoughts, desires and lives in abeyance from public consumption. Michelle Obama’s path to dissemblance has been fraught with struggle. Her candor in the early days of her husband’s campaign was a study in her failure to dissemble.

That time she was caught on camera rolling her eyes at John Boehner after he made a terrible joke is another example. While it is rare for any Black woman in the public eye not to hold her cards tight to her chest—Oprah is the exception—Michelle Obama has not seemed interested in gripping her cards as tightly as she has ultimately been forced to do.

In her love and admiration for Beyoncé, she tips her hand a bit. That relationship challenges a myriad of historical narratives that shape American public perception about Black women’s lives. Excepting Oprah and Gayle, we have rarely been treated to seeing unabashed admiration between two sisters at the top of their game. The other exception would be the Williams sisters, but then, they are actual blood kin.

Black women know full well that our lives are nothing without the sisters who inspire us, pull our cards, make us laugh uproariously, and show up for every manner of celebration or rescue mission, depending on what is required. We are our sisters’ keepers. So at one level, Michelle and Beyoncé’s relationship is not qualitatively different from any number of other powerful encounters Black women have, when we walk into a room, see that other sister winning, and catch the twinkle in her eye because the feeling— the pride—is mutual.

But we should not act like such Black women’s friendships are forged on easy terrain. We have to travel through a landmine of shame, stereotypes, distrust, and pain to get to each other. We have to pull off the shades and stop the dissimulation for just a moment sometimes to see and reciprocate that twinkle in the eyes—that look of recognition.

Michelle Obama and Beyoncé Knowles-Carter don’t travel across easy terrain to embrace one another. They travel through histories that would deny the visceral pleasure of sexiness to a First Lady like Michelle, and one that would deny the privileges of respectability to an otherwise traditional, privileged upper-middle-class Black girl like Beyoncé.

Both Michelle and Beyoncé are actively remixing the terms upon which Black womanhood has been cast. The denial of the right to ladyhood that has shaped Black women’s lives since the advent of slavery can no longer proceed un- checked into the twenty-first century. For Michelle Obama has been a consummate lady, despite her haters’ claims to the contrary. Like Bey said, “Y’all haters corny with that . . . mess.”

The thing is, though: maybe it was never Michelle’s goal to be the consummate Black lady. Maybe like many high-achieving Black girls, she wanted her ladyhood to be a strategy, a tool, a performance she could pull out of the briefcase when necessary, and store it away again when no longer required. On more than a few occasions, I’m sure the First Lady has wanted to tell some of her haters to bow down. For instance, her official White House portrait caused a minor controversy, when the First Lady opted for a sleeve-less dress for the photo. Two years later, Representative Jim Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin remarked that Michelle Obama had a “big butt,” and thus no business leading the Let’s Move! campaign. Surely she wanted to tell his ass to bow down. Sometimes ratchet is a more appropriate register in which to check your haters than respectability will ever be. But overtly ratchet Mrs. Obama simply cannot be. Beyoncé can be as ratchet as she wants to be though, and in this, I think the First Lady finds a place to let her hair down and put her middle fingers up.

In those moments, I can imagine Michelle reading the words of her critics, and responding like Beyoncé might: “You know you that bitch when you cause all this conversation.” Her husband has certainly followed Beyoncé’s husband’s lead in dealing with his haters, once famously “brushing that dirt off [his] shoulders,” in a speech, like Jay-Z told us all to do in response to our haters. The Knowles-Carters routinely provide anthems that the Obamas can live by.

The U.S. is no nation for Black women. It is too limited a container for the magic we bring. And because the American national imaginary is built on the most limited and stingy ideas about who Black women get to be, when we are called to navigate the terrain of racial representation as public figures, many sisters return to the most basic truth we have—we need each other to survive. Michelle Obama needs Beyoncé. I say need, not in the way that you need a drink of water. But rather in the way that you need to be able to see and love yourself—not only in your own eyes but in the eyes of another sister. Every sister who spends a fair amount of time navigating predominantly white professional environments knows that you need some kind of anthem to help you decompress after you twerk, wine, and two-step your way through racial micro-aggressions, while making that shit look like you waltzed.

For many, many of us, our anthems of choice come from Bey. She is our friend in our head, that girl that says the stuff that you wish you could say, but can’t.

In many ways, the friendship between Lady O and the King Bey is remarkable. But when you get right down to it, that kind of Black girl friendship is as regular as rain. Or maybe as regular as reign is more precise. When Black girls win, we all win. These two Black girls win on the regular, and long after they have departed their respective thrones, Black girls will win more easily because they were here—together.

From “Lady O and King Bey” by Brittney Cooper as published in The Meaning of Michelle edited by Veronica Chambers. Copyright © 2017 by the authors and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press LLC.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com