President-elect Donald Trump’s lawyers may have found a loophole in the so-called Bobby Kennedy law, Kellyanne Conway, who managed Trump’s campaign, said on Thursday. The federal antinepotism statute could limit the type of jobs he could give to his children, but Conway suggested that the Trump Administration might interpret it narrowly.

“The antinepotism law apparently has an exception if you want to work in the West Wing because the President is able to appoint his own staff,” Conway said on MSNBC’s Morning Joe. “Of course, this came about to stop maybe family members from serving on the Cabinet, but the President does have discretion to choose a staff of his liking.”

Already, his three children who work at the Trump Organization — Ivanka, Eric and Donald Jr. — are in an unusual position compared to many past presidential children, because they are integral to the President-elect’s career.

Now, as that business connection extends to sitting in on meetings with foreign leaders and being perceived as a valuable link to the Oval Office, they may join a select group of children and family members of Presidents who “worked” for their fathers in some way during their terms.

Experts say that so far the best parallel for the Trump children can be seen in Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s children. Since polio had rendered the President paraplegic, his children literally propped him up, and he leaned on his sons James and Elliott at important World War II–era conferences. Having the help of his children also meant that the President was not as dependent on his wife Eleanor as he otherwise would have been, which allowed her to have a public career of her own.

“Most people didn’t know he was a paraplegic, and as long as he could lean on strong arms, he could appear to be walking,” says Doris Kearns Goodwin, author of the Pulitzer Prize–winning biography No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II.

And when FDR’s daughter Anna moved into the White House in 1943, after her husband Clarence John Boettiger went into the Army, she essentially served as the First Lady during the last two years of her father’s time in office. Anna kept tabs on the President’s health and generally kept him company. “Roosevelt loved to gossip, and Anna was exactly the person to do that with,” says Goodwin, “which gave Eleanor the freedom to go away without feeling guilty.” That freedom allowed Eleanor to become “the most important First Lady probably in the history of the country” and transform the mostly ceremonial role into an activist one.

But Anna was doing more than just hosting state dinners. She was believed to be helping her father call the shots on matters of state.

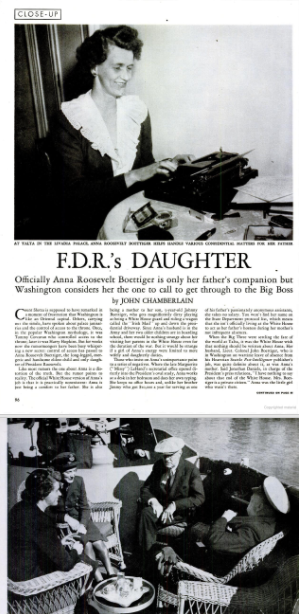

In early 1945, shortly before Roosevelt’s death, LIFE magazine declared that “Daddy’s girl has got her work cut out for her, running Daddy,” as a photo caption explained that “Anna Roosevelt Boettiger helps handle various confidential matters for her father.” The author of that profile, John Chamberlain, detailed the intense speculation as to what exactly Anna’s function was. He concluded she replaced Missy LeHand, FDR’s longtime private secretary, who had a stroke in 1941 and died a few years later. But there were still some aspects of her set-up that were mysterious:

The official White House version of Anna’s job is that it is practically nonexistent…Anna works at a desk in her bedroom and does her own typing. She keeps no office hours, and, unlike her brother Jimmy who got $10,000 a year for serving as one of his father’s passionately anonymous assistants, she takes no salary. You won’t find her name in the State Department protocol list, which means she isn’t officially living at the White House to act as her father’s hostess during her mother’s not infrequent absences…

She became the organizer of her father’s time. As her father’s “expediter,” which is the unlovely word used in Washington to describe her chief function, Anna sees to it that the right papers get to the right desks at the right moment. No official description of Anna’s day has ever been offered, but Democratic politicians discovered in early 1944 that Anna was the person to call if they ever wanted to get through to the Big Boss…

The feature went on to show photos of her by the President’s side while meeting with foreign leaders like U.K. Prime Minister Winston Churchill and France’s Charles de Gaulle. She even escorted her father to Yalta to meet with Churchill and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. While Chamberlain admitted that much of what was known about Anna’s role was hearsay, he noted that friends of Supreme Court Justice Bill Douglas said Anna “helped kill his chances” for the vice-presidential nomination, “which may mean that Truman is partly Anna’s creation.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

But Anna wasn’t alone. Sixteen children of Presidents worked in the White House with their fathers, by the count of Doug Wead, a former adviser to Presidents George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush and author of All the President’s Children, and even more had unofficial influence.

After Theodore Roosevelt’s daughter Alice became a media sensation, thanks to her pet snake Emily Spinach and her blue dresses that started a fashion trend of wearing “Alice Blue,” she was dispatched to represent the President on a 1905 voyage to Asia. Wead has a theory that “Teddy used her to divert attention, so his diplomats could sneak off the boat” and get their work done in peace. And it worked: in 1906 Roosevelt became the first statesman to win the Nobel Peace Prize for his role in negotiating the end of the Russo-Japanese War. Furthermore, the 21-year-old Webb Hayes became President Rutherford B. Hayes’ personal bodyguard and “right-hand man” — essentially filling the role we’d recognize today as Chief of Staff — according to the book A Son’s Dream by Meghan Wonderly. And Dwight Eisenhower’s son John worked as a White House assistant and frequent target of the President’s bad temper, says Joshua Kendall, author of First Dads: Parenting and Politics from George Washington to Barack Obama. (“He could let loose on [John] in a way he couldn’t with other aides,” Kendall explains.)

Some children even had offices in the White House. Wead claims Presidents would circumvent the antinepotism law by giving their kid an office in the White House and putting him or her on the party payroll, so they would get income from the Democratic or Republican National Committee rather than the government. (Neither the DNC nor the RNC responded to requests for comment about such a system.) “I argued strenuously in favor of George W. Bush going into the White House [during the first Bush administration] under that arrangement because I didn’t know how H.W. would run the government without W,” he tells TIME. “[People] thought they could say things to him that they couldn’t dare say to the father.” Wead says that not only was his advice unheeded, but that the first President Bush “laid down the law” that he would not allow nepotism (though he says a more distant Bush relative did end up working there).

Yet presidential children’s lives haven’t always been as glamorous as they seemed.

Shortly after George H.W. Bush was elected in 1988, Wead wrote a 44-page memo for his son and future President George W. Bush on where the kids of Presidents ended up — and it was dark. So dark, in fact, that TIME later commented that it could have been called “the Curse”: “The report detailed how Presidents’ kids had a tendency to become drunks or get sick, have an accident or die young,” according to the magazine. “Some quit their jobs or couldn’t hold them; some couldn’t get it together at all. George Washington Adams, the son of John Quincy Adams, is thought to have committed suicide at 28. Others walked away from colleges and universities, or they wrote bad papers and gave lectures about why Martin van Buren was right to oppose annexing Texas.”

So far, Trump’s older children appear unlikely to fall into that particular trap, as they seem loyal to him and established in their careers — though it remains to be seen what will happen after the inauguration.

“One of the worst things in the world is being the child of a President,” FDR once said. “It’s a terrible life they lead.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com