A curtain fell on western Burma on Oct. 9, the moment after police said Islamic militants attacked three security outposts along the border with Bangladesh, killing nine officers. Since that announcement six weeks ago, more than 100 people have been killed, hundreds have been detained by the military, more than 150,000 aid-reliant people have been left without food and medical care, dozens of women claim to have been sexually assaulted, more than 1,200 buildings appear to have been razed and at least 30,000 people have fled for their lives.

Humanitarian workers and independent journalists have been banned from affected areas as the Burmese army, known locally as the Tatmadaw, carries out what it calls “clearance operations.” The government, which is headed by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, said that those killed were jihadists — information that was gleaned, it said, through interrogations. The government said the rape allegations were false. It said that Muslim terrorists burned down the buildings themselves in an attempt to frame the army for abuse and claim international assistance.

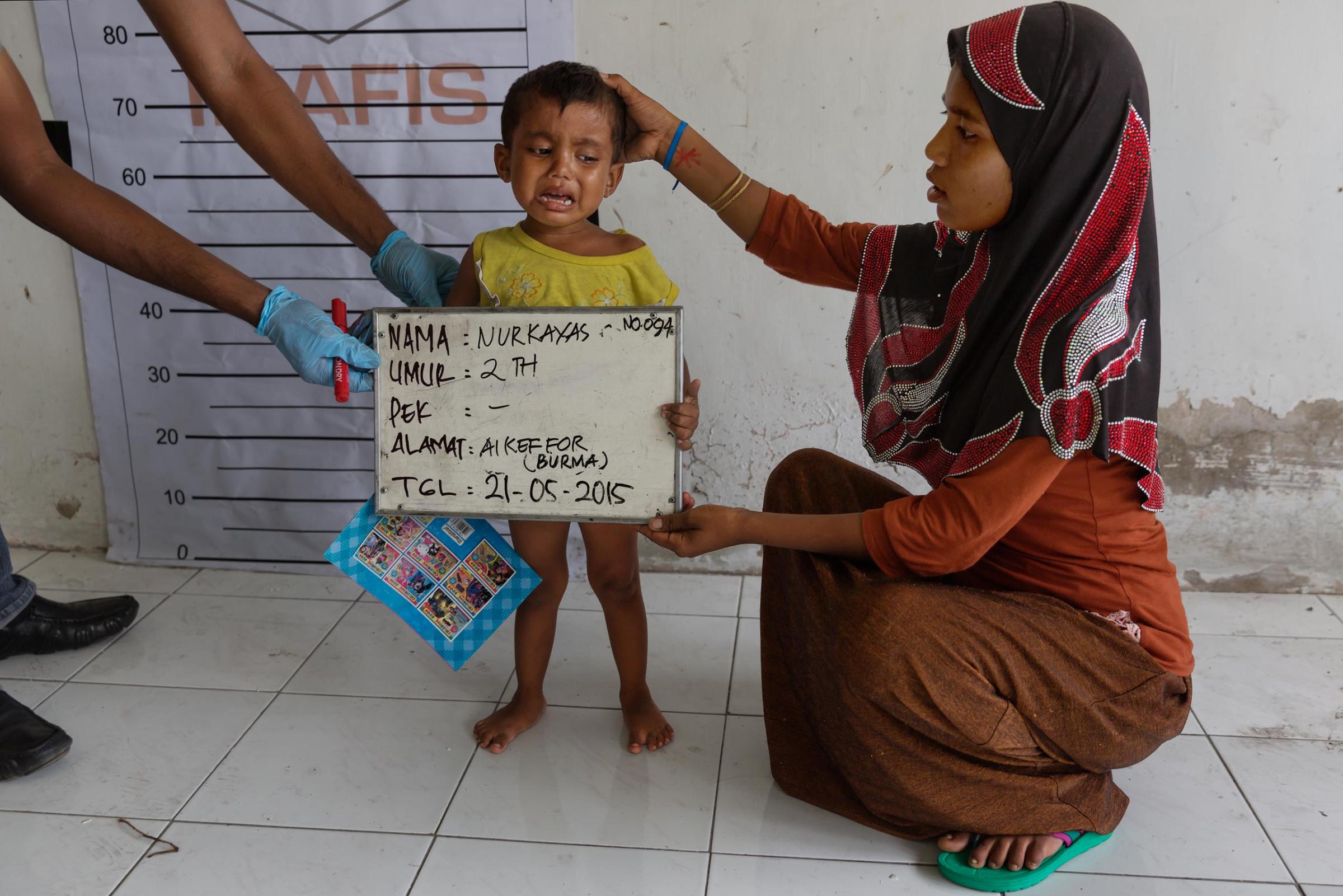

Counterterrorism operations are still under way in Maungdaw, the northernmost township of Arakan state, also known as Rakhine. The township is mostly populated by Rohingya Muslims, a minority that is denied citizenship and is viewed as one of the world’s most persecuted peoples. Elsewhere in the state, as in much of Burma, Buddhists are the majority. There are an estimated 1.1 million Rohingya in Burma. They are systematically denied political representation. They are demonized in the national media. They are so geographically and economically isolated that tens of thousands have fled on dangerous boat voyages, attempting to reach Malaysia.

Read More: Rohingya Women ‘Raped at Gunpoint’ in Burma Army Sweep for Suspected Jihadists, Report Says

Suu Kyi, whose party secured a landslide win in elections in Nov. 2015, has made few public remarks on the conflict simmering along the country’s western coast. While human-rights advocates have criticized her silence, some political analysts say the issue has exposed the limits of her power; the military still controls the key Ministries of Home Affairs, Border Affairs and Defense.

Events since Oct. 9 have been bleak. It is difficult to envision a positive outcome for the Rohingya, who have been subjected to what Human Rights Watch has called ethnic cleansing. Others have claimed that the Burmese government has laid the groundwork for genocide. There are also allegations that some among this marginalized community may have turned to violent extremism. This unknown number of suspected militants, armed with sticks, spears, slingshots and a few hundred stolen firearms, has summoned the force of one of Asia’s most formidable national armies against an entire community of poor and disenfranchised villagers.

This is how the events in Arakan unfolded:

Oct. 9: Police said three border-guard posts were attacked by hundreds of Islamic militants, killing nine policemen. Eight assailants were reportedly killed by security personnel immediately following the attacks. Police initially claimed the attackers had links to a group called the Rohingya Solidarity Organization, a militant group that is largely believed to have been defunct for decades. The area was put on military lockdown and declared a counterterrorism “operation zone.”

Read More: The Military Continues to Search for Suspected Jihadists in Western Burma

Oct. 10: Humanitarian aid was completely suspended. Troops were deployed to the areas surrounding Maungdaw, Buthidaung and Rathedaung towns in northern Arakan state. An estimated 162,000 people in the area normally receive life-saving assistance from the World Food Programme and other U.N. agencies.

Within days of the lockdown, more than 800 Arakanese Buddhists arrived in the state capital Sittwe. More than 1,200 Muslims fled their villages and sought shelter in Buthidaung town. State media reported that Buddhists were being evacuated by helicopter citing safety concerns; Buddhists reportedly feared that their villages would be ambushed by mobs of armed Muslims.

The New York Times reported that a dozen people may have been extrajudicially killed since the initial attacks.

The Plight of the Rohingya by James Nachtwey

Oct. 14: The government said the assailants were members of a jihadist group, Aqa Mul Mujahidin, which authorities claimed was led by a man who was trained by the Taliban in Pakistan and financially supported by foreign terrorist groups. A few days later, while on a trip to India, Suu Kyi told the Hindustan Times, “That is just information from just one source, we can’t take it for granted that it’s absolutely correct.”

Oct. 27: Fiona MacGregor, a Scottish investigative journalist for the Myanmar Times, reported that rights groups had documented dozens of sexual-assault cases allegedly committed by Burmese security forces against Rohingya women in the operation zone. The following day, Reuters reported the same allegations. The editorial staff of the Myanmar Times, which is the country’s paper of record and its only private English-language daily, was instructed not to report on the situation in Arakan until further notice. (Coverage resumed on Nov. 18 under a new policy.)

MacGregor was targeted by the former Information Minister Ye Htut and presidential spokesperson Zaw Htay on social media. Online harassment ensued.

Read More: Burmese Police Say They Will Arm and Train Non-Muslims to Counter Suspected Jihadists

Oct. 31: MacGregor was fired for “damaging the good name of the paper.” She had worked there for more than three years, and wrote a popular column focused on women’s issues. She routinely covered issues such as sexual assault and women’s health, particularly in conflict zones.

“It is profoundly concerning for women’s rights, media freedom and democracy as a whole in Myanmar, that the civilian government is using bullyboy tactics to intimidate journalists and attempt to silence allegations of rape by the military,” MacGregor tells TIME. “We should not forget that at the center of this propaganda war are real people who are allegedly the victims of the most horrible and brutal crimes.”

Her editor, Douglas Long, was also fired two weeks later for “undermining the mission of the paper” shortly after he spoke about the incident with international media and a representative of the Committee to Protect Journalists.

“With each passing day,” Long told TIME just days after MacGregor lost her job and a week before he lost his, “the current government is starting to look more and more like the pre-2010 government.”

Nov. 1: State-controlled media began publishing op-eds refuting journalism that contradicted the official narrative — hearkening back to the prereform era of censorship and heavy-handed propaganda. These columns claimed that Islamic militants had gone too far by attacking security forces, and should be purged. State media also accused international media of working “in collusion with terrorist groups” to spread fabricated news.

Nov. 2: A delegation of nine diplomats and one U.N. official visited parts of Maungdaw for the first time since Oct. 9. The highly chaperoned trip lasted two days, during which they visited four villages selected by the government. While members of the convoy — which included U.S. Ambassador to Burma Scot Marciel and U.N. resident coordinator Renata Dessallien — were allowed to speak with some villagers, the visit was tightly controlled. Authorities detained at least two Rohingya men while they were speaking with members of the delegation. Ambassador Marciel insisted that they be freed immediately. Reports surfaced that some people who had spoken with the delegation were later detained and beaten.

Members of the delegation declined to comment directly on their observations, stressing that theirs was not a fact-finding mission, and urging the government to allow access to humanitarian workers, technical experts and journalists. The government has yet to adhere.

The Rohingya, Burma's Forgotten Muslims by James Nachtwey

Nov. 3: Arakan state police chief Colonel Sein Lwin said that local police would begin arming and training a civilian security force of non-Muslim residents. The training scheme, which the International Commission of Jurists has referred to as “a recipe for disaster,” was meant to begin on Nov. 7 for about 100 recruits. Reuters reports that the plan is already under way in the state capital Sittwe.

Nov. 12: The Burmese army opened fire with helicopters near villages in Maungdaw. The state-controlled newspaper Global New Light of Myanmar reported that some 60 assailants armed with “guns, sticks and spears” had attacked soldiers, killing one. The military responded by firing into the fields from two helicopters. The two days of ensuing violence alone displaced an estimated 15,000 people, and videos that have reached international aid workers appear to show dead bodies lying in the fields. The government said 69 “violent attackers” were killed and 234 were arrested. These numbers are increasing by the day.

Some observers have called the army’s response to the alleged terrorist threat “heavy-handed,” others have compared it to the so-called “four cuts” strategy used throughout the decades to isolate the country’s myriad armed ethnic insurgent groups. But according to Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch, operations against these “ragtag Rohingya militants with a few guns, some sticks and spears” are different.

“The real comparison is the Tatmadaw’s penchant for scorched earth tactics when they feel like they are challenged in any way, and that’s why some of the Rohingya villages where the authorities suspect militants may have hidden are being targeted for looting and burning, and sweeps have taken away so many men and boys,” Robertson tells TIME.

Nov. 15: Burma’s state media introduced the True News Information Team of Defense Services, which singled out local and regional media outlets for publishing “fabrications” about casualties and damaged property. At least one local Muslim journalist has since been subjected to extreme online harassment, including death threats.

Nov. 18: Humanitarian access has not been restored in Maungdaw. Following the diplomatic visit in early November, the U.N. was allowed to deliver limited food assistance to about 7,200 people in four villages. This meager delivery was only expected to last about two weeks, and will expire at a time of year when food scarcity is at its height. Supplies are expected to dwindle sometime this week.

Regular food, cash and nutritional assistance to more than 150,000 people have been suspended since Oct. 9, according to Pierre Peron, a spokesman for the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Burma. During this period, more than 3,000 children under 5 have not received their treatment for severe acute malnutrition, leaving up to 50% of them seriously at risk of dying. Primary health care to about 24,000 people per month has stopped, which Peron says is “very worrying, considering that infant and maternal mortality rates in Maungdaw are historically up to four times the national average.”

The U.N. special rapporteur on human rights in Burma, Yanghee Lee, called on the government Friday to take immediate action. “The security forces must not be given carte blanche to step up their operations under the smoke screen of having allowed access to an international delegation,” Lee said.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com