The doorbell rang at 4.30 a.m., politely at first and then more insistently. When Drisia, a French Muslim citizen, finally staggered out of bed and opened the door, she faced 10 armed police officers in riot helmets. They stormed into her apartment in a town in the French Alps, rifling through her drawers while her seven-year-old daughter cowered nearby. Days after that police raid on Dec. 3 last year, her employers fired her—after 10 years of service—from her administrative job with the company that manages the Mont Blanc Tunnel connecting France to Italy, on the suspicion of links with potential Islamist terrorists. “I asked what had happened, but they said the decision was made at a level far above them,” Drisia told TIME on Thursday, adding that she was still too shaken to have her full name in print. “There was no explanation,” she says. “They marched me out like a suspect.”

Read More: Putin Cancels France Trip After President Hollande Accuses Russia of War Crimes in Syria

Drisia is hardly alone. France has been under a state of emergency since ISIS sympathizers mounted the deadly Paris attacks last November 13, massacring 130 people in the bloodiest terror attack in years. President François Hollande imposed the raft of supposedly temporary security measures within hours of the attacks, while the country was reeling from the bloodbath. The new rules allowed police to raid houses across the country for the first time during nighttime hours, and with little judicial oversight; place suspects under house arrest for months; ban street demonstrations; and monitor millions of people’s communications. Since then pieces of these supposedly temporary measures have migrated into French law, including a broad expansion of surveillance powers for police and intelligence agencies. “We are in a changed time, and in many ways, we also have a changed people,” French Interior Minister Bernard Cazeneuve, the architect and overseer of the new tactics, told local magistrates and police chiefs at a gathering in Paris on November 7.

This Sunday, France marks the first anniversary of the Paris attacks with solemn ceremonies to honor the dead and finally move beyond grief and unease. And yet, one year on, it is far from clear whether the government’s anti-terrorism strategy is working. In interviews with regular French people over the months, almost all say they are resigned to the fact that another terror attack is inevitable, somewhere, sometime. Desperate to avoid a repeat of the Paris massacre, the government has reassured few people that they are capable of averting assaults especially from lone-wolf attackers—and indeed some believe its anti-terrorism campaign might even have inflamed the situation.

Read More: Dismantling the Calais ‘Jungle’ Camp Won’t Be Enough

In a report released last week, the Paris-based International Federation of Human Rights, or FIDH, says France’s anti-terror tactics have been “a serious setback to the rule of law,” but asserts that the country is no safer from jihadist attacks. Describing dozens of police raids on seemingly innocent people, the report notes, “There is little evidence that this approach is working and it comes at a cost to fundamental rights.”

Lawyers tackling cases under the state of emergency say police have largely targeted Muslims who look conservative—men with long beards or women in long dresses and headscarfs. Many, they say, are regarded in the streets and at work as potential jihadists—a feeling they believe the state of emergency has only helped to cement. “The government created a theory that when you are becoming more and more religious, in an orthodox way, you can become a terrorist, or make an allegiance to terrorism,” says Arié Alimi, a Paris lawyer, who is suing the government in about 15 different cases of wrongful arrest or police abuse under the state of emergency. “These people have nothing to do with terrorism,” says Alimi, himself an observant Jew. “They are just Muslims.”

Read More: The ‘Left Behind’ Refugees of the Jungle in Calais

Indeed, the state of emergency has targeted almost entirely the 5 million or so French Muslims—the biggest Muslim population in Europe. That is hardly surprising, since the jihadist attackers have all been Muslim, and have acted in the name of aAl-Qaeda or ISIS. “There is this kind of witch hunt where you are looking for anybody related to conservative Muslim movements,” says Marwan Mohammad, executive director of the French Collective against Islamophobia, or CCIF. He his group has received 320 reports of police abuse since the Paris attacks. “The vast majority involved are innocent families with no reason to suspect them.”

Alimi says several of the clients suing for police abuses or wrongful arrests under the state of emergency are French converts to Islam. Those converts are frequently more religious than Muslim-born French people. The converts Alimi represents include Willy Benali, a 30-year-old , a sniper for the French military who has fought in Gabon, Central African Republic and Kosovo, and whom police raided shortly after the Paris attacks. Another is a man in the Val D d‘Oise region northwest of Paris, who runs an import-export business, and who did not want to be named in print; he too is a convert to Islam, whose Jewish grandparents were killed in Nazi concentration camps during the Second World War. Shortly after the Paris attacks local authorities, and placed him under house arrest for four months, eventually clearing him after Alimi sued the government. In the court findings, the magistrate describes what led authorities to suspect the businessman, saying that ISIS has instructed French Muslims to adopt “techniques of dissimulation,” in order to hide their jihadist allegiances. “When you read the conclusions of the administrators, there are very racist, disciminatory remarks,” Alimi says.

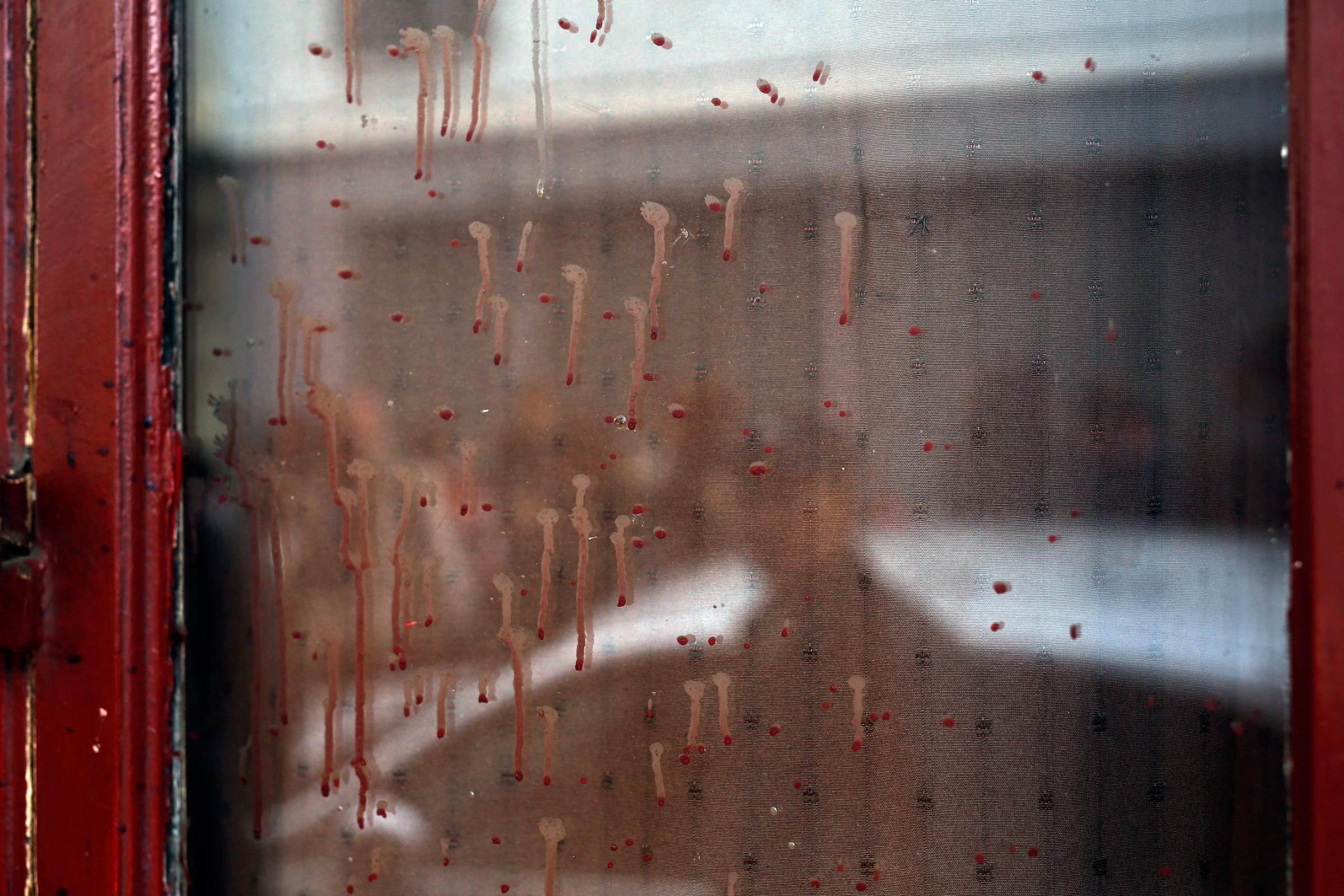

Photographing the Aftermath of Paris’ Terror Attacks

At the heart of these accusations are the police themselves—and they aren’t happy either. Heavily criticized for failing to stop a series of terror attacks, they are on a constant lookout for the next eruption of jihadist violence—a terrifying prospect that is always in the back of many French people’s minds. “We have the means now, but it is not sure that they won’t be further attacks,” says Christophe Crépin, spokesman for the national police trade union, UNSA. “There is a savagery that is very, very strong now.”

Crépin says police feel deeply rattled, even burned out, in the face of a cryptic and nimble enemy that has outmaneuvered them. “The state of emergency has helped us in terms of raids,” he says. “But it mobilizes a lot of police. And if you never have a vacation, and you are always under stress, you cannot function.”

The limitations of the police tactics were starkly clear last July 14—Bastille Day. That day President François Hollande trumpeted his anti-terrorism success in a televised holiday address and said he would soon end the state of emergency. Hours later, however, a Tunisian immigrant delivery man, Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel, rammed a giant truck into a holiday crowd on the Nice promenade, killing 87 people—France’s second-biggest terror attack, after Paris.

After the Charlie Hebdo attacks in January 2015, which killed 17 people in separate incidents over a few days, the Nice attack was the third jihadist assault in 18 months. Worse, it appeared to emerge from nowhere. Despite months of police raids, intelligence monitoring, and hundreds of arrests, Bouhlel, 31, had no police record and no known jihadist connections or sympathies. While ISIS claimed him as its “soldier,” that was news to the police, and his friends. “He didn’t do Ramadan, he didn’t pray,” one acquaintance told TIME in Nice. Within hours of the Nice massacre, Hollande immediately reversed himself, reimposing the emergency measures; days later, the French parliament made some of those measures law.

Now it is left to lawyers like Alimi to sort out the consequences—and to those targeted to prove their innocence. Drisia, the woman fired from her job at the Mont Blanc Tunnel in the French Alps, has yet to find new employment. With the help of the organization CCIF, she won a six-figure compensation package in court from the company—the exact figure remains secret under the settlement—and a small sum from the regional authorities. While that has helped, she says she has struggled to find new work, especially since local newspapers widely publicized her firing, saying she was “on the path to radicalization.” Drisia, who is a single mother of a girl recovering from a brain tumor, believes police targeted her as a suspected jihadist, because “I was someone who adhered to religion even though my daughter had cancer,” she says. “It has affected me a lot. This has been a very difficult year.”

For France, there are likely to be more tough times to come.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com