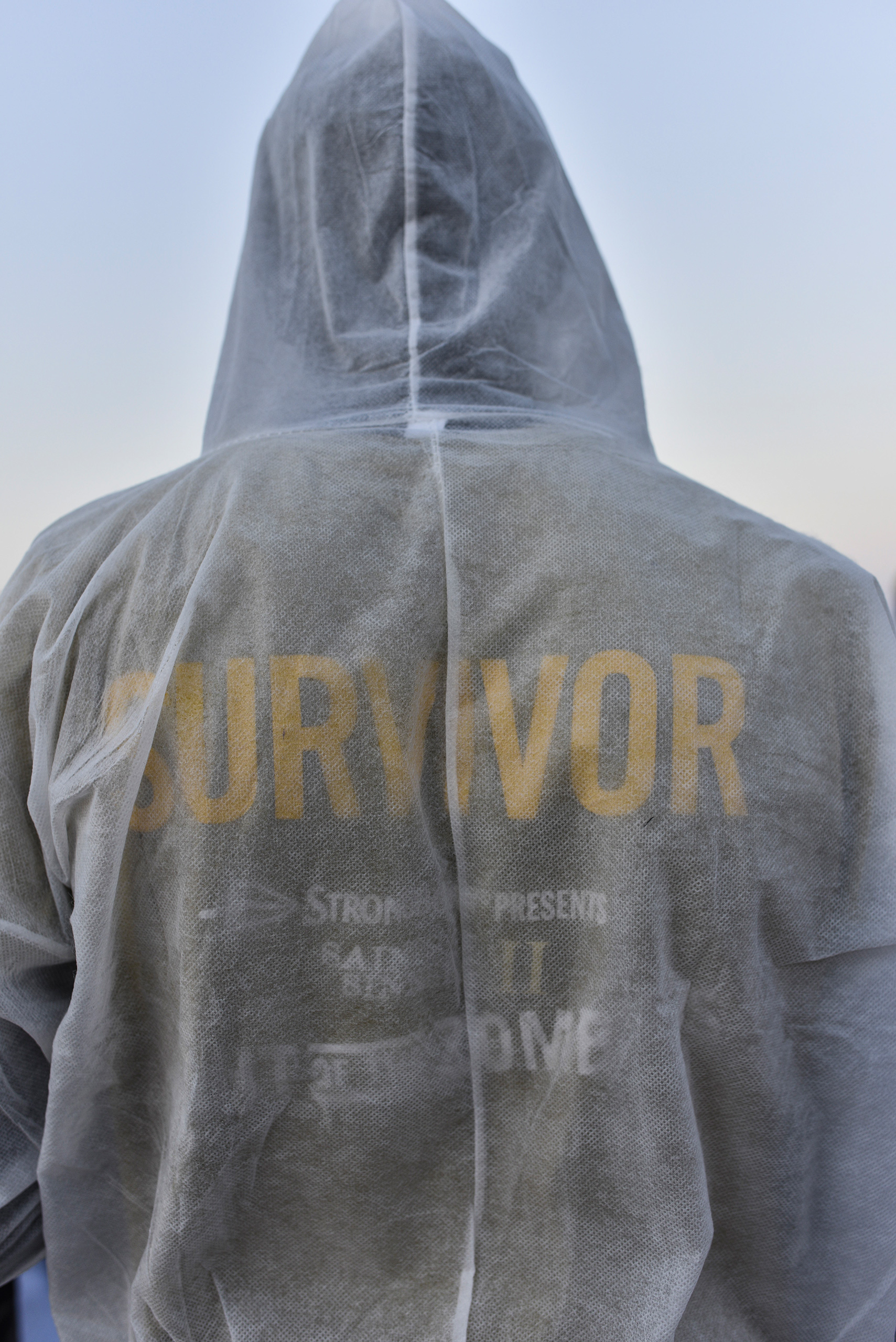

The two Somali boys had trekked for months together on their hair-raising journey to Europe, sleeping side by side in Sudan, Libya, on a packed boat on the Mediterranean and in camps in Italy and France. Then earlier this week, government officials plucked one of the two teenagers from the ramshackle refugee camp in Calais known as the “Jungle” in northern France and bused him across the English Channel. He was taken to what had long been the boys’ Promised Land: Britain. His friend was left behind in France, left to grapple alone with his uncertain future.

Read More: What to Know About the Controversy Over Child Refugees Arriving in the U.K.

These so-called “left-behinds,” as the relief workers in Calais’ refugee camp call the youth still hunkered down in tents in the Jungle, have deepened the anxiety and tension roiling the camp, according to aid volunteers speaking to TIME on Friday, as French officials prepare to demolish the settlement forever, perhaps as soon as Monday.

After months of squabbling between the British and French officials over which country holds responsibility for the refugees hunkered down in Calais, both governments are now scrambling to shut the Jungle, leaving the fate of the camp’s 1,000 or so youth younger than 18—children under the law—in legal limbo. French officials say police will begin clearing the camp on Monday morning, first registering all 3,000 or so residents, before transferring the adults to small refugee centers across France, while housing the unaccompanied minors in temporary containers in Calais. After that, their asylum claims will wind their way through the bureaucratic labyrinth that could take years to navigate.

Read More: Hungary’s Mistreatment of Refugees Today Ignores History

So far about 50 children have landed in Britain from Calais over the past week, after officials concluded they were eligible for settlement in the U.K. under the E.U.’s immigration laws because they have a sibling, parent or an aunt or uncle in the U.K. Their arrival in Britain has been met with relief from refugee organizations, but also fury from some Britons who accuse the youth of gaming the system, by pretending to be younger than they really are. It can be hard to tell—the great majority of unaccompanied minors, who hail largely from Eritrea, Sudan, Afghanistan and Somalia, have arrived in Europe without a single identity document.

About 400 of the children camped in the Calais Jungle claim that they too have close relatives in Britain, but have not yet been able to prove their case. Left behind without the tenuous support system of friends that has been built in the Jungle, they have grown deeply anxious over where they will end up—and increasingly so, as the camp’s residents have begun scattering in advance of the demolition.

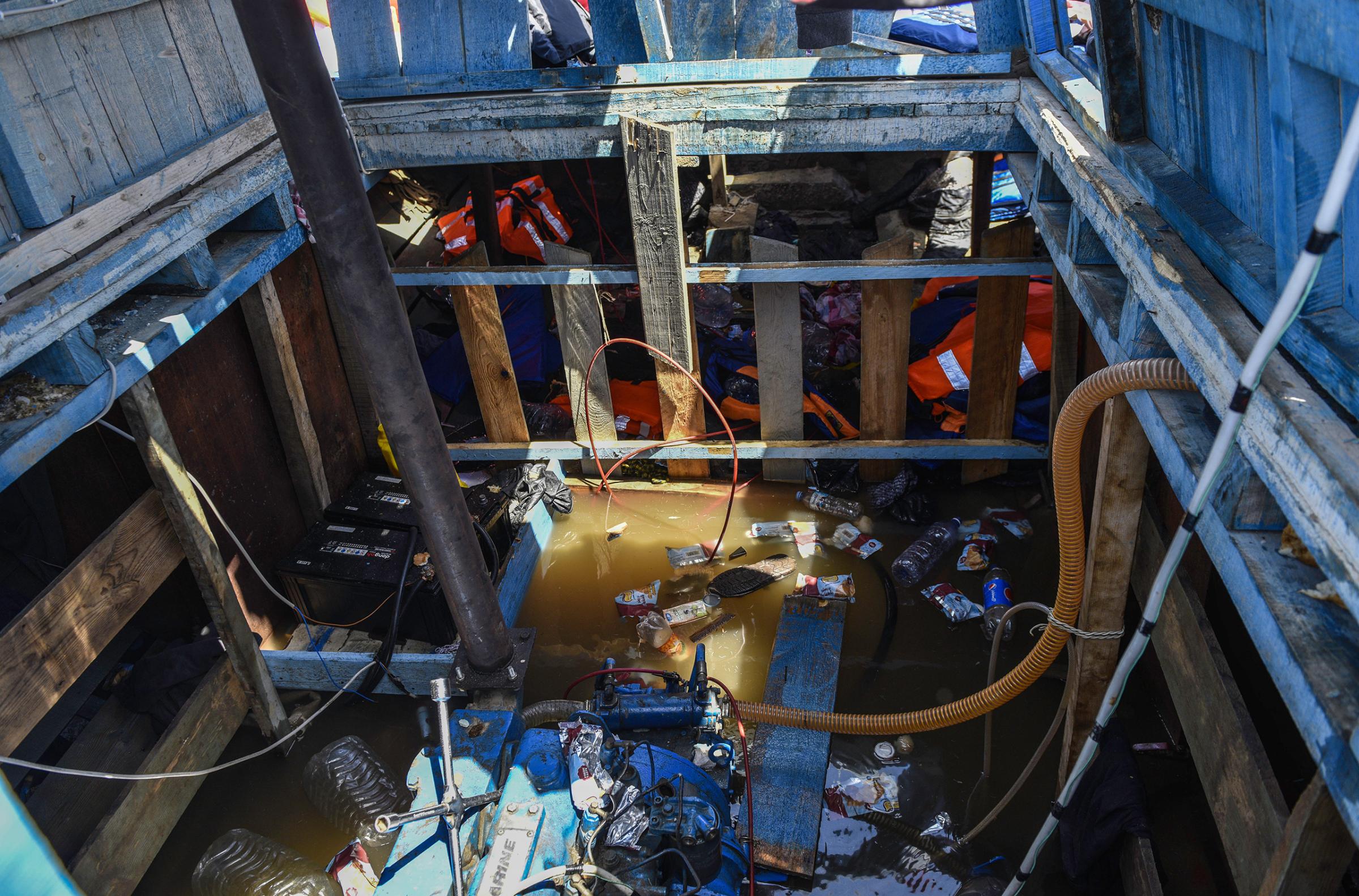

Migrants’ Last Hope: A Rescue on the Mediterranean Sea

“There is a massive increase of people going off, leaving the camp,” says Malcolm Astell, a British educator who has worked as a volunteer teacher in the Jungle since early September, and who recounted the story of the two Somali boys. (TIME could not independently verify their tale.) “The big problem now is the ‘left-behinds,'” he says. “They all hope they will be the next ones on the next bus.”

As Britain has opened the door to some child refugees, however, others find themselves separated from the closest people in their lives. To the Somali teenager in Calais, he says, his friend’s departure brought overwhelming sadness. “This lad was his only friend, then he’s suddenly whisked off to England, and he is left here alone,” Astell says. “I cannot imagine it.”

Making matters worse, volunteers have in recent days shut many of their activities in the Jungle, including the English and French lessons in Astell’s makeshift Jungle Books classrooms on the edge of the tent camp. These services have provided a crucial sense of normality amid the chaos, but have become difficult to maintain while residents and volunteers are preparing for a mass demolition. “We decided it was more urgent to get basic supplies to people, so that when they move form here, they have got winter clothes, boots, coats,” says Astell, who spoke from an aid organization’s warehouse, where he was collecting items for refugees.

With the end of the Jungle drawing near, the atmosphere in the camp is one of near panic, according to volunteers, with refugees scheming secretly how to escape the French authorities, or where to find alternative routes to Britain—many of them dangerous. “Tensions are running really high,” Alexandra Simmons, a field worker volunteering with the French refugee organization l’Auberge des Migrants, said on Friday. “There are fewer people in the camp, and no one is sharing information about where they are going.”

The fear among many refugees is that once French officials fingerprint them and register their names, they could be rejected for transfer to the U.K. if they cannot prove they have relatives there, and might also be rejected for asylum in France, if they cannot show a rightful claim. In addition, officials might conclude that some of those who claim to be under 18 are really adults, and so are not automatically entitled to government care.

In fact, although both France and Britain have vowed to shut the Jungle permanently, many working with the refugees in Calais say that is unrealistic, especially since people have camped around the port city for at least 15 years, well before the refugee crisis gathered strength, in an attempt to sneak across the Channel.

After months of political wrangling over the Calais refugees, many youth had simply given up all hope in the legal asylum process, as TIME reported last month. One 15-year-old Eritrean in that story, who we named Aron, had tried sneaking across the Channel hundreds of times during his 11-month stay in the Jungle—and finally made it across to Britain, smuggling aboard a truck earlier this month. So long as success stories like that filter back to the “left-behinds” in the Jungle, Calais will draw those attempting to reach Britain.

Aid groups expect that many of the refugees will resist being transferred to centers around France, since they are determined to go to Britain. So while the French government—which faces a tough reelection battle next Spring—has said it is determined to permanently shut the refugee camp. “No one imagines that this is going to change the geography of this area,” says Norbert Clement, a lawyer in Calais working on refugee claims. “To imagine that no refugees will come to Calais again is a fairy tale.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com