For all of its staggering construction statistics—90 million pounds of steel, a million square feet of glass, enough concrete to build a sidewalk from New York to Chicago—One World Trade Center’s most fundamental building blocks are intangible. It is made up of stories, no more or less than words, of those who built it, those who use it and those who will never see it.

Many of the stories are about those who lost their lives. Millions of other, intangible, losses, hover in solidarity around the souls of the 2,983 people who died at Ground Zero in 2001 and 1993. Many survivors, including those who were not downtown or even in New York City on 9/11, continue to suffer from an emptiness that they cannot quite define. Over the course of speaking to dozens of people about the new World Trade Center, I relived those losses. The first story shared was always about 9/11—where they were, how they escaped, and why they were compelled to rebuild. It was a holy ritual.

Each conversation revealed the interconnectedness of the past and present. These stories provided the psychological means, critical to the mourning and rebuilding process, of reconciling loss. With every retelling, the past comes alive and grief recedes a little bit more. It is the way we rebuild our lives—and our buildings. Now, with most of the Trade Center completed, we can begin a new chapter.

On this 15th anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks, I am more keenly aware than ever of the recovery that has taken place downtown. The more I examine the seven structures that have emerged in the intervening years, the more clearly I see that they are part of the continuum of healing that began inside the Twin Towers even before they fell. The stories, too, began immediately.

Many who built the new towers either worked on the original towers or had family members who did. The fathers of ironworkers Tom Hickey and Mike O’Reilly placed the Twin Towers’ steel. Later, in 1985, while working on 7 World Trade Center, O’Reilly’s father fell and was paralyzed from the waist down. September 11 called O’Reilly to the profession and, eventually, he signed a beam at One World Trade Center: “This one’s for you, Pop.” Hickey, a fourth-generation ironworker, was driven by family pride and also the need to restore One World Trade Center on behalf of those who were lost. Each was after the wholeness that comes with completion, especially here where completion demanded everything they had to give. Along with thousands of others, the ironworkers showed their reverence for the dead by rebuilding Ground Zero.

Rudy King, an Information Officer for the Port Authority, accompanied me on interviews with those who built the Trade Center because of the fact that they, like me, were working under strict nondisclosure agreements to protect the safety of this most vulnerable of places. He said little during these meetings, only indicating with a slight frown or a raised eyebrow when an interviewee was getting dangerously close to mentioning a security feature that could not be discussed. Although Rudy intimated that he had been at the Trade Center on 9/11, it wasn’t until after the book was published, and he wrote about working on it, that I learned that he had been there in the clouds of debris, one of tens of thousands who have suffered post-traumatic stress ever since. Our working together, he said, “freed something in me that had been caged since 9/11,” a testimony to the healing power of stories.

Others say that the towers themselves were the givers. Steven Segarra, a guard at One World Trade Center, told me that the tower had given him back his life. After helping with Ground Zero’s cleanup in 2001, he was traumatized, lost his job and home, and struggled with alcohol. Still, he says, “9/11 changed me for the better. I used to be a narcissist, but not anymore.” Before landing a job on One’s security detail, he had been doing odd jobs and living at the Salvation Army. Pride that he had been entrusted with the safety of this tower and its occupants poured out of him like a benediction. Some days, it’s hard to know whether we were watching over the towers or if they were watching over us.

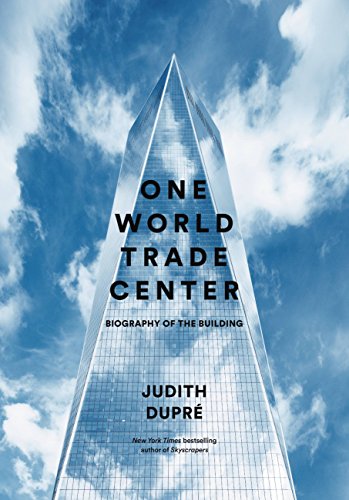

Together, we have witnessed the World Trade Center’s determined rise. Three, soon to be four, skyscrapers encircle the voids of the memorial pools. Their foursquare appearance and palpable strength are a comfort, given those last terrible images of collapse we hold in memory. Works of art that transmute grief to beauty, the new towers were designed to appear timeless, and they do. At the same time, they insist on the present moment, as their glass facades change with every passing cloud, every nuance of blue sky, every face of the passersby who appear fleetingly in their story. Girded with steel and hope, they are taller than tall. They stand as a promise of healing and wholeness, perhaps not yet for some, and not ever for many, but their skyline pledge endures: Life, however unfathomably diminished, continues.

One World Trade Center and every other structure on the site hold our impossible wish: to have back everyone who was lost on September 11. We will never forget those who died. But, like those who rebuilt the Trade Center, we will honor their memories by supporting each other—friends, strangers, our city, our nation—with kindness, strength and stories. We will rebuild each other.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com