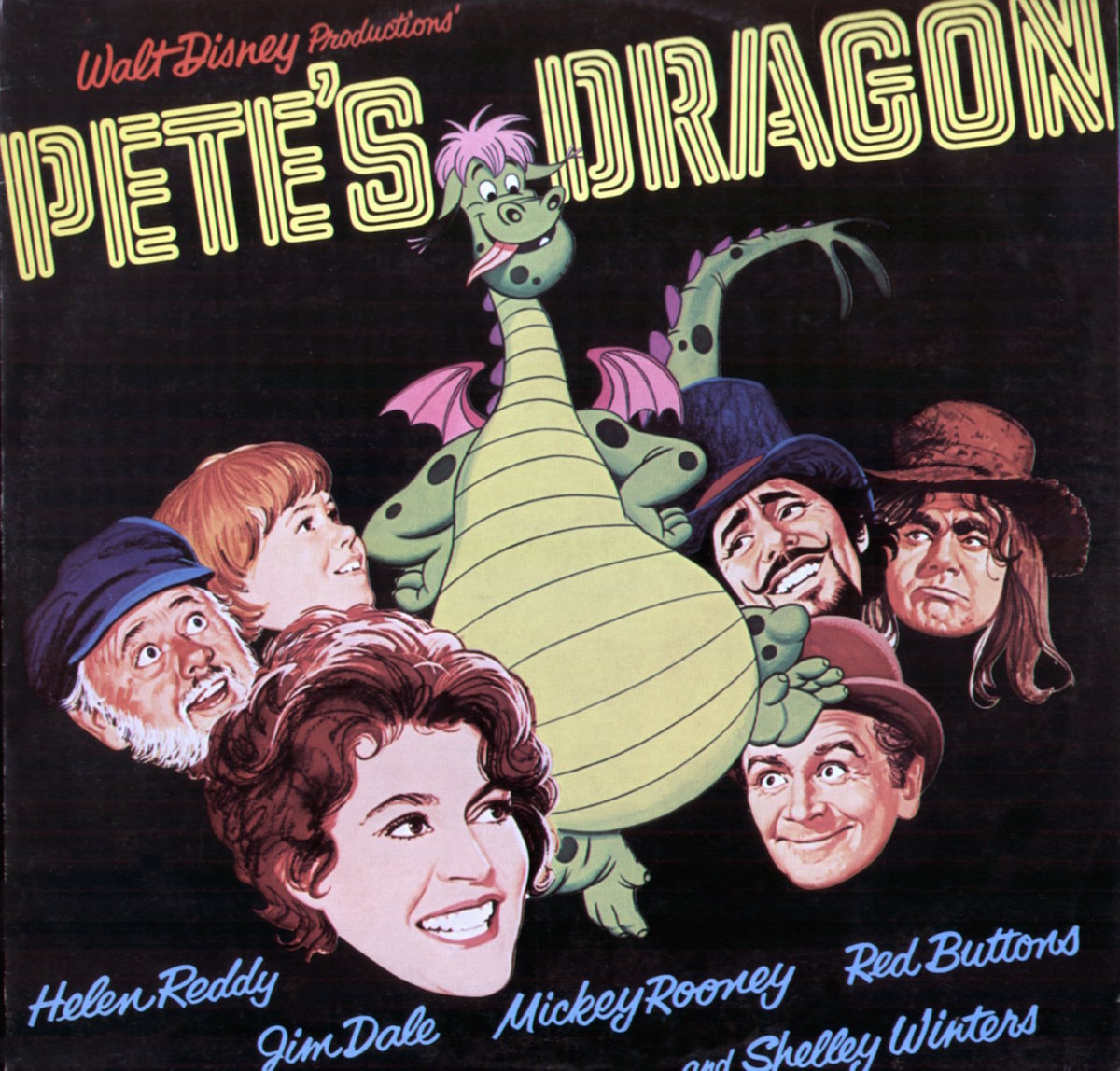

The new Disney version of Pete’s Dragon is hardly a remake of the plot of the 1977 film with which it shares its name: it still has a dragon and a kid named Pete, but the live-action-plus-CGI drama promises fewer goofy pratfalls and songs, and more modern angst and sweeping orchestral scoring.

The ’70s version was, as TIME described upon its release, the story of an orphan boy “so appealing that you want to strangle him” and his dragon friend, as they make an impression on the denizens of a 19th-century Maine town. And, though its songs were dismissed as “a good opportunity to line up for more popcorn,” the overall impression was charming enough that perhaps it should be no surprise the title is being reused.

As TIME critic John Skow wrote, the live-with-cartoons romp was fun, largely due to the help of said dragon:

He’s gorgeous, in a ghastly sort of way: the fine-featured, thoughtful face of a moose, though greener than your normal moose; little scrambly front legs and big thumping back legs; a great, green, swaying belly and a proper thrashing tail; all supported by demure pink wings set too far forward for really good aerodynamics, so that he flies with a waddle. He fulminates fire, of course, if he has remembered to change his flint, and, all in all, it’s just as well that he is invisible most of the time. His name is Elliott.

Elliott has an active sense of humor, and thereby hangs a scaly tale, amiably told and only slightly overproduced by the Disney organization in time for the Christmas trade. There is an orphan boy, of course, played by a cute, smudge-cheeked red-haired kid named Sean Marshall. An urchin of this description appears in every Disney movie, and the viewer is half convinced that Disney grows them on its own Devils Island, using the cute ones for films and chaining the ugly ones to drafting tables to paint animated green dragons, frame by agonizing frame.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

And, Skow noted, it arrived at an apt moment. Speaking of the “in the nick of time” nature of a major plot point, he noted that “nicks are another reason that the 1890s are good for story writing; modern times don’t seem to have nicks, only a lot of existential despair” and that some adult viewers of the film would likely feel a wistful yen for a dragon of their own, to “scare a little appreciation and respect from an uncaring world.”

Nearly 40 years later, surely plenty of adults could still appreciate that desire.

Read the full review, here in the TIME Vault: Scaly Tale

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com