Thais head to the polls next week to vote in a referendum designed to breathe life into what has become a stagnant democratic process. An affirmative vote on Aug. 7 will see Thailand adopt a new constitution — its twentieth since 1932.

Junta leader Gen. Prayuth Chan-ocha, who seized power in 2014, has promised general elections next year — but not before a fresh constitution is adopted. But that next step is by no means a fait accompli for, once again, Thailand is polarized as many fear that Prayuth and his cadres are getting a little too comfortable in the government’s shoes.

While there are undoubtedly some who approve of the substance of the draft charter, which was painstakingly drawn up by a military-appointed committee, millions of disillusioned Thai citizens just want to see the wheels of democracy moving again.

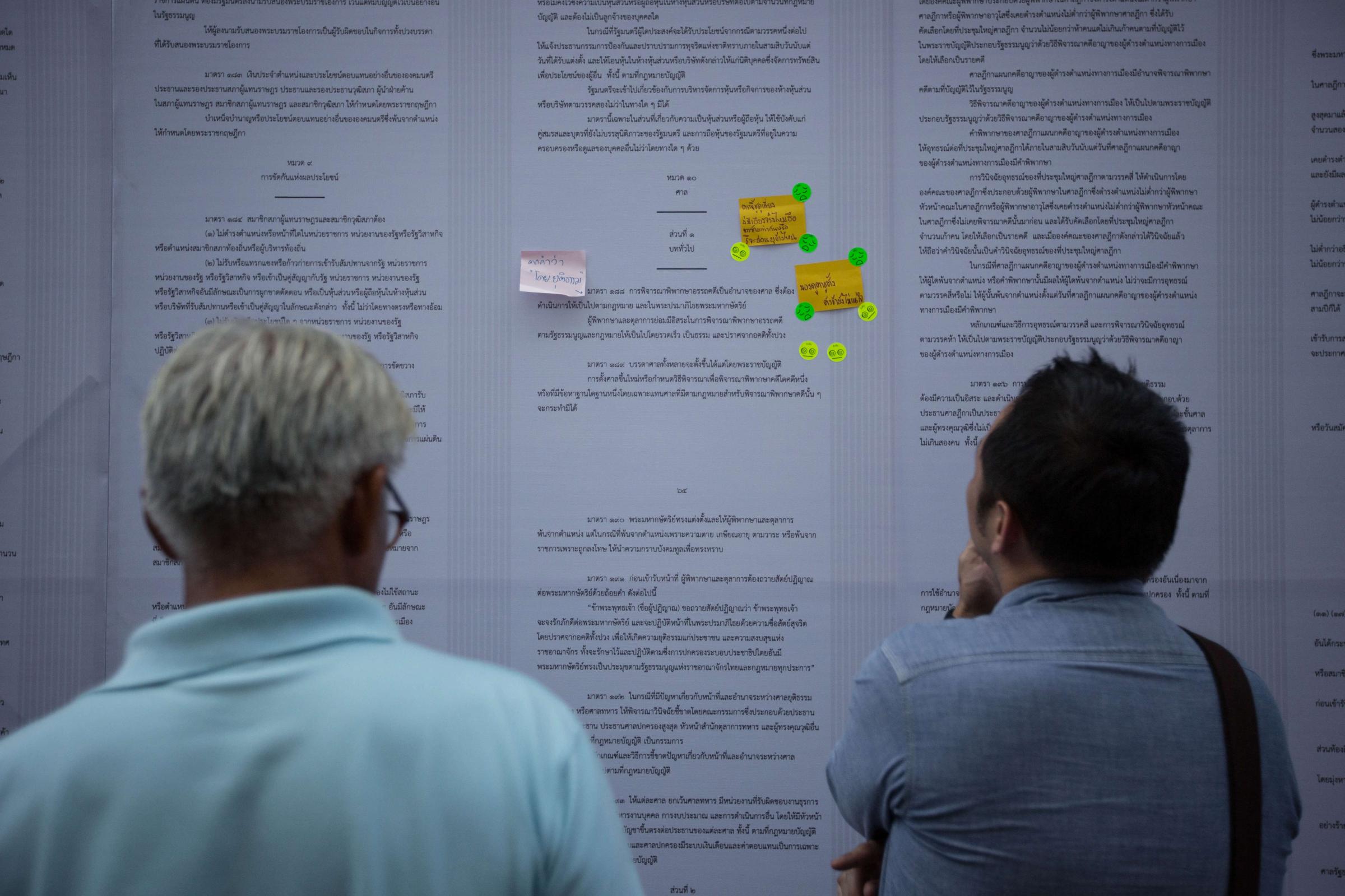

Released publicly in March, the revised constitution has been touted as an edict to finally combat the endemic culture of corruption that pervades the country’s politics. The word “corruption” is mentioned no less than 46 times in the draft charter, with robust promises of organic laws and mechanisms “to rigorously prevent and eradicate corruption and misconduct,” as well as sweeping powers bestowed upon a nine-member National Counter Corruption Commission, which will be appointed by the King. The 94-page document also contains strong provisions on healthcare and education.

But critics say approval of the charter would entrench the junta’s grip on power, allowing it a large say in government even after it has left office. The new constitution would allow the military the opportunity to advocate its own candidate for prime minister, and permit it to step in and dissolve parliament at whim.

Read More: Thai Junta Leader Warns Opposition Not to Monitor Upcoming Referendum

“I will vote ‘yes’,” says Nina, 48, a Bangkok businesswoman. “Because I believe it will solve the problem of government corruption.”

Father-of-two Komol, a furniture retailer in the southern city of Suratthani, says he will vote “yes” to the draft constitution because it includes 12 years of free public education for children.

In the northern city of Chiang Mai — a traditional stronghold of the opposition “Red Shirts” and their patriarch former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra (ousted in a 2006 military coup) and his sister Yingluck (ousted in the 2014 coup) — opinion is mostly unequivocal.

“I will definitely vote ‘no’,” says university lecturer Namwaan. “Yes is a vote for dictatorship. No is for democracy.”

Physician Dr. Voravit echoes the sentiment. “The message is clear: this process is simply an exercise in legitimizing an illegitimate dictatorship. The bottom line is that the vote is meaningless — the dictatorship will continue one way or another,” he says. (Some of the interviewees in this story did not want to give their full name for security reasons or fear of reprisals.)

In the lead-up to the referendum, a ban has been imposed on campaigning, or more specifically, campaigning for a “no” vote. Thai media have been threatened with closure under the guise of national security, and to date, no less than 113 individuals have been prosecuted for voicing opposition to or criticizing the roadmap.

“The government has tried to censure opinion on the draft constitution by arresting and charging opponents under its Referendum Act,” says Sor Rattanamanee Polkla, a human rights lawyer with the Community Resource Centre Foundation in Bangkok. “It does not allow dissenters to campaign,” she tells TIME, pointing to even the mildest of political activities, such as the distribution of leaflets, and in particular an incident a few weeks ago at a university campus when students were detained by police for releasing balloons into the air inscribed with the message: “Campaigning is not wrong.”

Official paranoia hit fever pitch in the central town of Kampaeng Phet last weekend when two eight-year-old girls were charged with “obstructing the referendum process, destroying official documents and destroying common public property.” The pair had simply torn a voter list from a notice board because they wanted to play with “the pretty pink paper.”

Press coverage of the referendum has been similarly discouraged. On July 22, a 30-day blackout was ordered on Peace TV, a station loyal to the opposition Red Shirts. The National Broadcasting and Telecommunication Commission accused it of “reporting information that caused confusion, provocation, incited conflict and caused divisiveness”.

Prayuth, who is now acting prime minister, has been the focus of much whispered derision. He endures a tumultuous relationship with the Thai media, frequently losing his temper and ridiculing members of the press. His behavior at press briefings has been, at times, bizarre. In November, he astounded onlookers by massaging the ear and ruffling the hair of a reporter; then, a few weeks later, he tossed a banana skin at a cameraman. Most famously, when asked what he would do with journalists who did not toe the government line, with a dead-pan expression he quipped, “Probably just execute them.”

Read More: The Draconian Legal Weapon Being Used to Silence Thai Dissent

In early July, another attempt at levity seemed to go over the heads of reporters when he said that if the draft constitution were rejected in the polls, he might just have to write a new one himself. He later claimed the remark was made tongue-in-cheek.

But not everyone’s laughing. International media watchdogs have come out strongly against the interim government in recent weeks. On July 12, Reporters Without Borders noted that Thailand has “seen drastic curbs placed on media freedom since the military staged a coup in May 2014.”

The Committee to Protect Journalists’ senior Southeast Asia representative Shawn Crispin tells TIME, “Nobody is sure where the line lies for permissible comment, so criticism of the draft and process has been significantly limited.”

Both watchdogs, alongside the Bangkok-based Foreign Correspondents’ Club and domestic press associations, have called for charges to be dropped against Taweesak Kerdpoka, a reporter for the news group Prachatai, who was arrested on July 9 in the western province of Ratchaburi along with four campaigners from an anti-coup student organization, accused of possessing materials urging a “no” vote. If convicted, the five each face a maximum prison sentence of 10 years under the junta’s Referendum Act — for publishing or distributing content about the draft constitution “which deviates from the facts.”

A similar crackdown took place in northern Thailand in early July, when the Election Commission announced it had intercepted more than 2,000 leaflets that carried false information, most notably that the new constitution would annul pensions, free education and healthcare.

So what then is the choice for Thailand’s 50 million voters a week on Sunday?

Question 1. on the ballot is simple: “Do you accept the 2016 draft of the constitution?” (Not that many citizens have read it). Question 2. is somewhat more nebulous: “Should the Senate be allowed to join the House of Representatives in the voting process to select a prime minister for a five-year period?”

Herein lies what critics claim is written proof that the military junta will likely resist giving up power overnight.

Both the Upper and Lower Houses of parliament were abolished after the 2014 coup. The Upper House, or Senate, consisted of 150 members. The new charter would enshrine a new Senate made up of 250 members, all of whom would be initially appointed by the ruling junta. Although the House of Representatives would continue to comprise 500 lawmakers under the 2016 constitution, the collective strength of a military-friendly Senate could tip the scales against any majority political party in a bicameral parliament, opening the doors to a non-elected prime minister — in effect, a constitution-backed military general or ally.

The few academics who are not too afraid to speak out say that the junta’s draft constitution is weighted heavily in favor of the current regime retaining a stranglehold on power.

Read More: Thai Junta Defends Itself From U.S. Criticism Over Its Decision to Give Police Powers to Soldiers

“By all accounts, the referendum will be approved because the law and the bureaucratic apparatus have been mobilized to ram it through. A rejection would be a huge blow to the military government and a bare exposure of its lack of legitimacy,” political scientist Thitinan Pongsudhirak of Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University tells TIME.

“Yet there is an outside chance of rejection because the two main […] parties — the Pheu Thai and Democrats, respectively — are against it.”

Though no polls or forecasts are permitted, indications are that younger voters, especially students, will vote “no.” The elderly, who maintain steadfast loyalty to the monarchy and are far less enthused by the new generation of politicians, will probably accept the military’s charter.

If the referendum fails to deliver a majority “yes” vote, some immediate questions arise: What criteria will be placed on a fresh constitution? Who will draw it up? How long will it take? Can elections be postponed indefinitely while this process drags on?

Kavi Chongkittavorn, a senior fellow at Bangkok’s Institute of Strategic and International Studies, believes that, whatever the result, Thailand’s economy will not be adversely affected.

“Thai private sectors are used to political uncertainties. In this case, the stock market will respond to the long-term potential of [the] Thai economy, not the short reactions,” he says.

And so, for Prayuth and his clique any result may be a winning hand: either they are given a seal of approval by the Thai populace, or they remain in power as caretakers for the foreseeable future while the country wrestles with a constitutional crisis.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com