A good way to become very popular is to be on your deathbed. Everyone wants to stop by, drop off a casserole (I’m in the Midwest), say the deep and meaningful things they always meant to say, have a poignant moment, a cinematic hand squeeze.

A deathbed is really not the time for that, though. If you’re worried about making sure people know how you feel, go ahead and do that right now. This can wait. But once Aaron was admitted to hospice care at age 35 our phones kept dinging and buzzing and lighting up with messages from long-absent friends and long-lost family near and far who suddenly and urgently needed to be a part of my husband’s death.

At first, I tried to be a good messenger.

“Aaron,” I whispered to him after my phone lit up with an offer for a casserole from a couple we’d last seen 18 months before, “the so-and-so’s want to stop by to see you. What do you think?”

Aaron lolled his head from side to side, his eyes struggling to find focus, like a broken doll.

“No.” he finally sighed, and slipped back into the gray space between this world and the next.

Aaron was always popular. And not because he was a cookie-cutter Popular Person. In high school, he was a skater punk with pierced ears who ended up as Prom King. He was a well-loved fixture in the Minneapolis ad community, and known for standing in the back of company photos and taking off his shirt. He was also just a genuinely really nice human. For the first year we dated, there wasn’t a place in Minneapolis we could go without him running into a friend. A friend, to Aaron, was anyone he’d ever met. Old classmates from grammar school, one-time colleagues from many jobs ago, people he’d met through friends of friends of friends at Karaoke night. Once he was diagnosed with brain cancer, the circle widened: hospital administrators and nurses would stop us at brunch or on runs around Minneapolis to say hello.

That was Aaron’s nature: to make people feel loved and accepted, no matter how small a part they played in his life.

A blog I started during his sickness extended that circle to thousands of strangers around the world, who followed our little family through two brain surgeries, more chemo than I can count, one beautiful baby born and one lost.

Our email and Facebook inboxes were filled with strangers around the world who were going through some version of what we were going through, or who weren’t, but appreciated the opportunity to try on some hard feelings before they had gone through any life disasters.

But as that virtual circle got bigger, the real-life circle grew smaller. Like Jay Gatsby, we had plenty of people show up for the flashy stuff: a wedding that was crashed by dozens of acquaintances and watched virtually by hundreds of people around the world, a funeral/party for Aaron in a cavernous art gallery that was packed with people I hadn’t seen since that wedding, some of whom had stood up beside us as our wedding party.

I am from a generation (not quite a Millennial, not a gen-xer), that is prepared for anything: we have steadfastly contributed to our 401(k)s, gone to therapy to correct the damage our parents inflicted on us in the 80s, read Lean In. But we’re still completely disarmed in the face of actual hardship. And that includes me, too. This is the part where I tell you I’ve posted a very heartfelt tribute about my friend’s dead son on Facebook, but I’ve yet to go see her in person.

Watching someone’s life and death from the safe distance of your phone screen is one thing. Stopping by to see a dying person is quite another. Hard things are hard to see, and many people who had loved Aaron chose not to see us, not really. Where we’d expected that big group of friends to keep us company, we had a very small group of friends who showed up for Game of Thrones on the couch and dinner in the hospital. We had a few people who weren’t afraid to hear the real answer when they asked “how are you?” And everyone else drifted away, appearing in the form of Instagram likes and Facebook shares, texted well wishes that could be delivered without awkward silence or eye contact, without the messy exchange of emotions. And I didn’t notice their absence until they were there trying to elbow their way back in to the most personal moment in our lives.

Dying is private, intimate. There is no such thing as a peaceful death, or a natural one. We are drugged from this world to the next, and our bodies fight violently to live, even when it is a lost cause. I could see Aaron’s heart beat through his chest. His body jerked with breath, long after he’d lost consciousness.

Dying is not an occasion for you to stop by to unburden yourself of things unsaid and things undone. The dying person does not care. They have more pressing matter to attend to. Aaron spent nine days between this world and the next. His big green eyes, once so lively, were unfocused and wet. The brain tumor had clipped his speech and paralyzed the left side of his body, his olive skin had turned gray, his limbs were little more than bone and skin, like the elderly men we’d seen wasting away in their hospital beds on the oncology floor, who looked as though their beds were about to swallow them up. I went, in four short years, from Aaron’s Internet crush to his girlfriend to his wife to his caretaker, the last one being my greatest horror and my greatest honor, the one with secrets I’ll keep forever.

That is not an easy thing to explain to people who have suddenly decided it is time to grace your threshold with their presence. It is not Instagram-friendly to post about how your lively, jovial husband can no longer swallow pain medication, so you carefully squeeze a dropper of methadone into the corners of his mouth every few hours. You do not feel like Tweeting about how his breath is ragged and rattly, a death rattle. You know that from the movies. And Facebook is not the place to let people know that your house smells like death and you don’t give a shit about dinner.

“Why did you wait until now?” I wanted to reply, “You should have had FOMO when he was sitting on the couch in a chemo haze, looking at Instagram photos of you all out at parties you hadn’t invited him to!”

But I know that they waited because they didn’t know how to do show up, outside of double-tapping their phone screens. They didn’t know how to cross the line between the public documenting of our lives on Facebook and Twitter and Tumblr and Instagram, and the private hell we’d been wading through.

It doesn’t matter, though, who showed up and who didn’t. It wouldn’t have changed the inevitable outcome.

Aaron’s and my experience hadn’t felt lonely, because it wasn’t. We were the center of one another’s worlds, and we had each other. Our online personas were not a lie, but like everything in social media, they weren’t the whole truth, either. It was our lives cropped into a series of square photographs, condensed into 140 characters, summarized in neat blog entries and Facebook posts. It was an attempt to organize the frenetic horror of illness and death, to manage all of the noise inside and around us into something palatable for everyone else.

Aaron died in my arms on November 25, alone in the house we’d shared. I’d told our family and friends, who had been keeping us company and wiping my kitchen counters and getting me drunk enough to sleep at night, that they needed to leave. Our family needed to be alone again, to go through this last phase together. That is the natural order of things, for your circle to get smaller and smaller. Our son, not yet two, climbed into bed alongside his father and kissed him. “Guh-bye!” he said, “I luh you!” and climbed down to the floor to toddle out of the room. It was me and Aaron, alone in bed, the way it was each night and every morning. Outside, the world moved along in its usual way. Inside our house, the only sound was Aaron’s breathing. And then it was quiet.

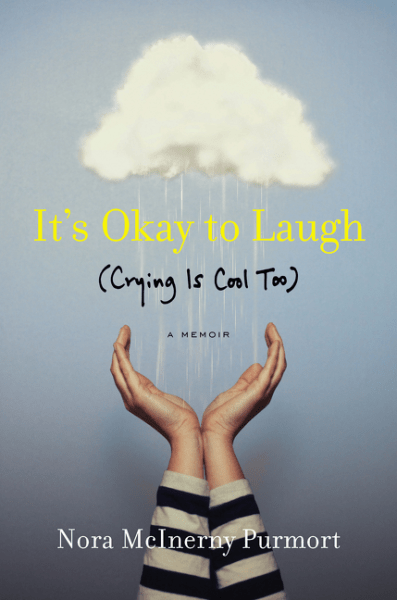

Nora McInerny Purmort is the mother of Ralphie, the author of It’s Okay to Laugh (Crying Is Cool, Too), and the host of the forthcoming American Public Media podcast Terrible, Thanks for Asking, which launches November 2016.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com