Few photographers can claim the kind of legacy left behind by Charles “Teenie” Harris. Over a 70-year career that spanned photojournalism for the Pittsburgh Courier, studio portraiture, and snapshots, the African American shooter (who died in 1998) captured nearly 80,000 images — mostly of Pittsburgh, specifically the Hill District — that form a dynamic, unparalleled record of 20th century black urban life. Civil rights leaders, superstar athletes, and celebrities sit alongside everyday people celebrating birthdays, mourning losses, and protesting discrimination amid the tumult of urban renewal.

The Carnegie Museum of Art, which controls Harris’ archive, has done a superb job of mining it for hyper-focused exhibitions that speak to our present circumstances as much as provide a window on the past. The latest show, Teenie Harris Photographs: Great Performances, guest curated by actor Bill Nunn and on view through July 17, features 75 images from 1938 to 1978 centered on performance in the black community — an especially potent topic in the wake of the #OscarsSoWhite controversy.

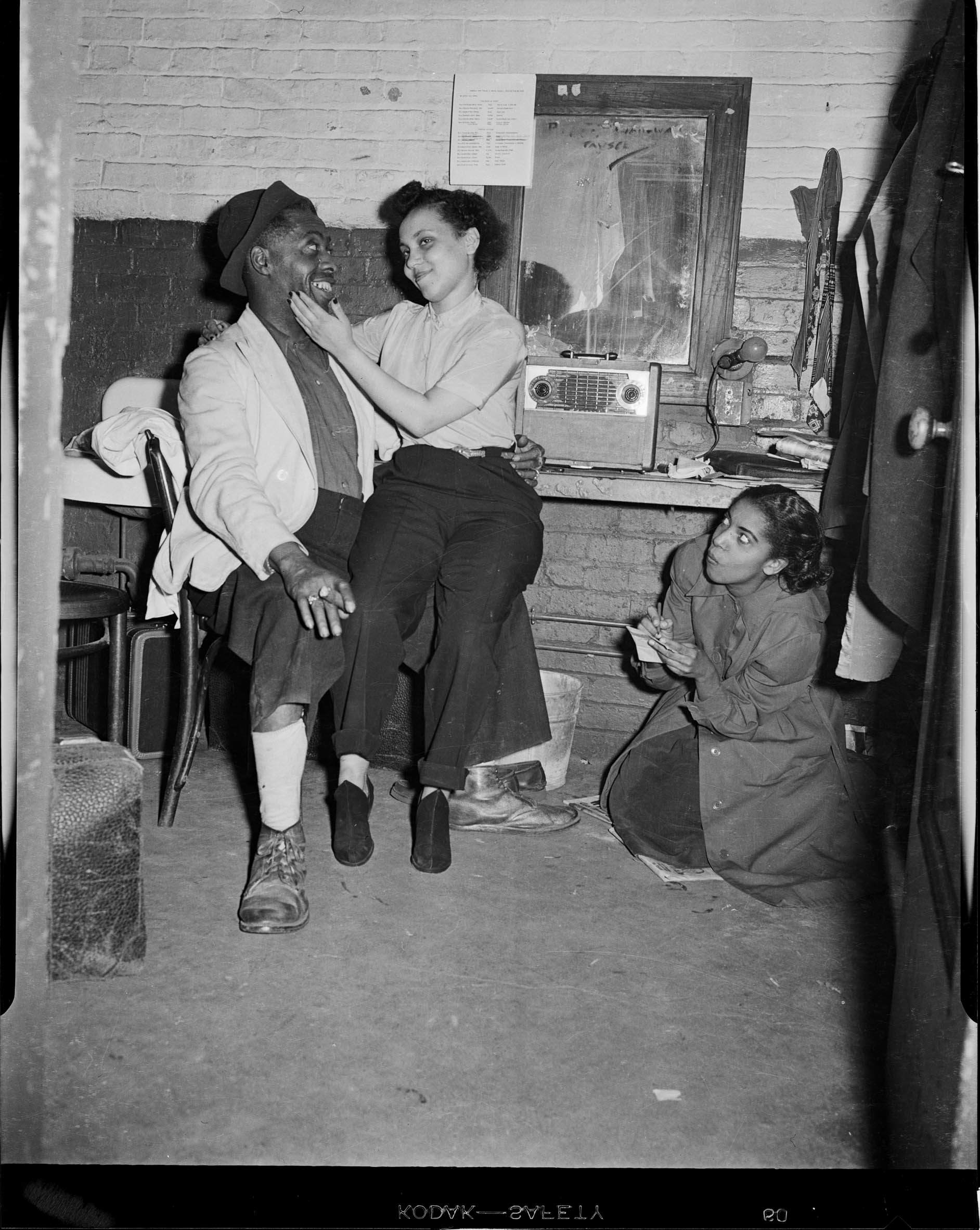

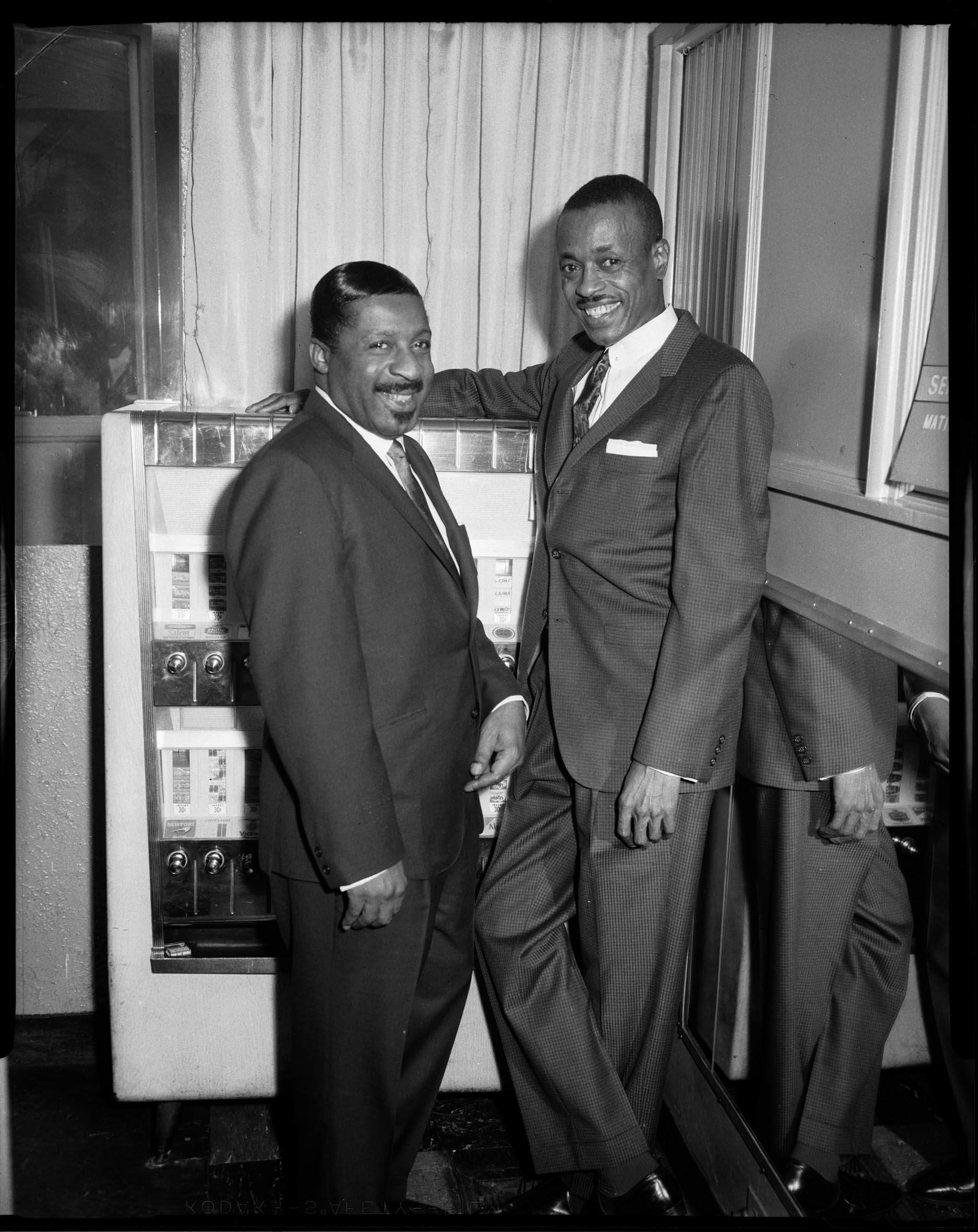

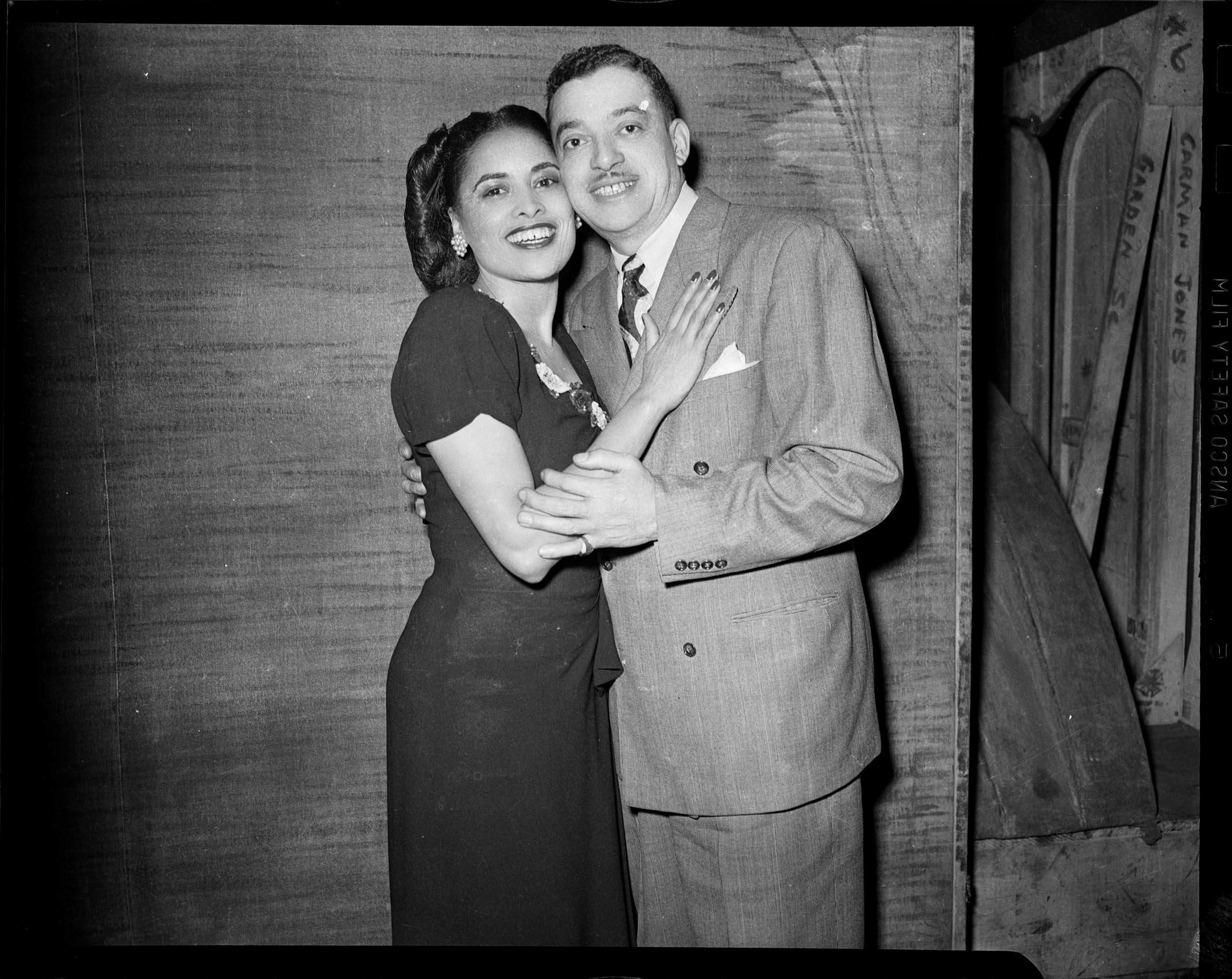

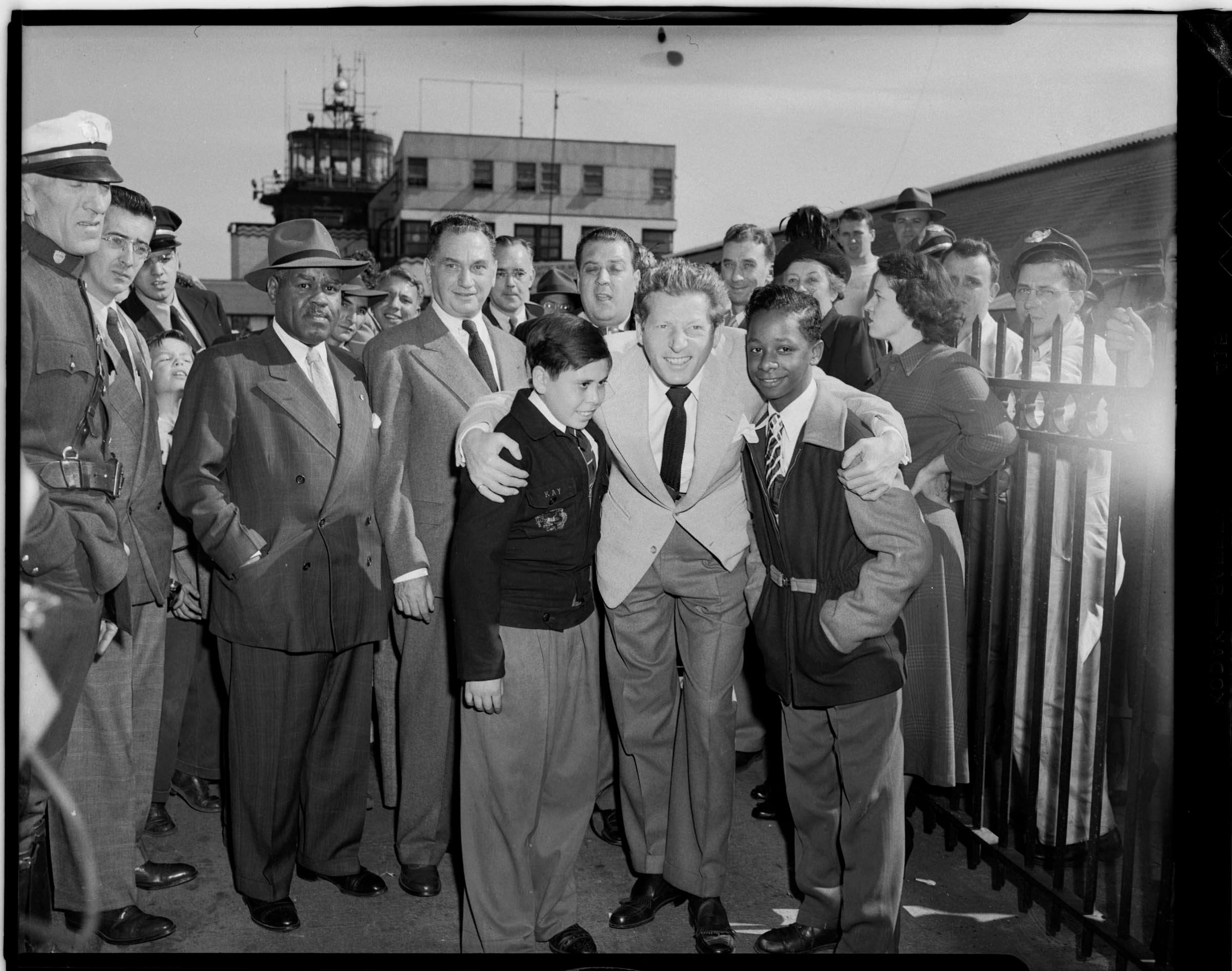

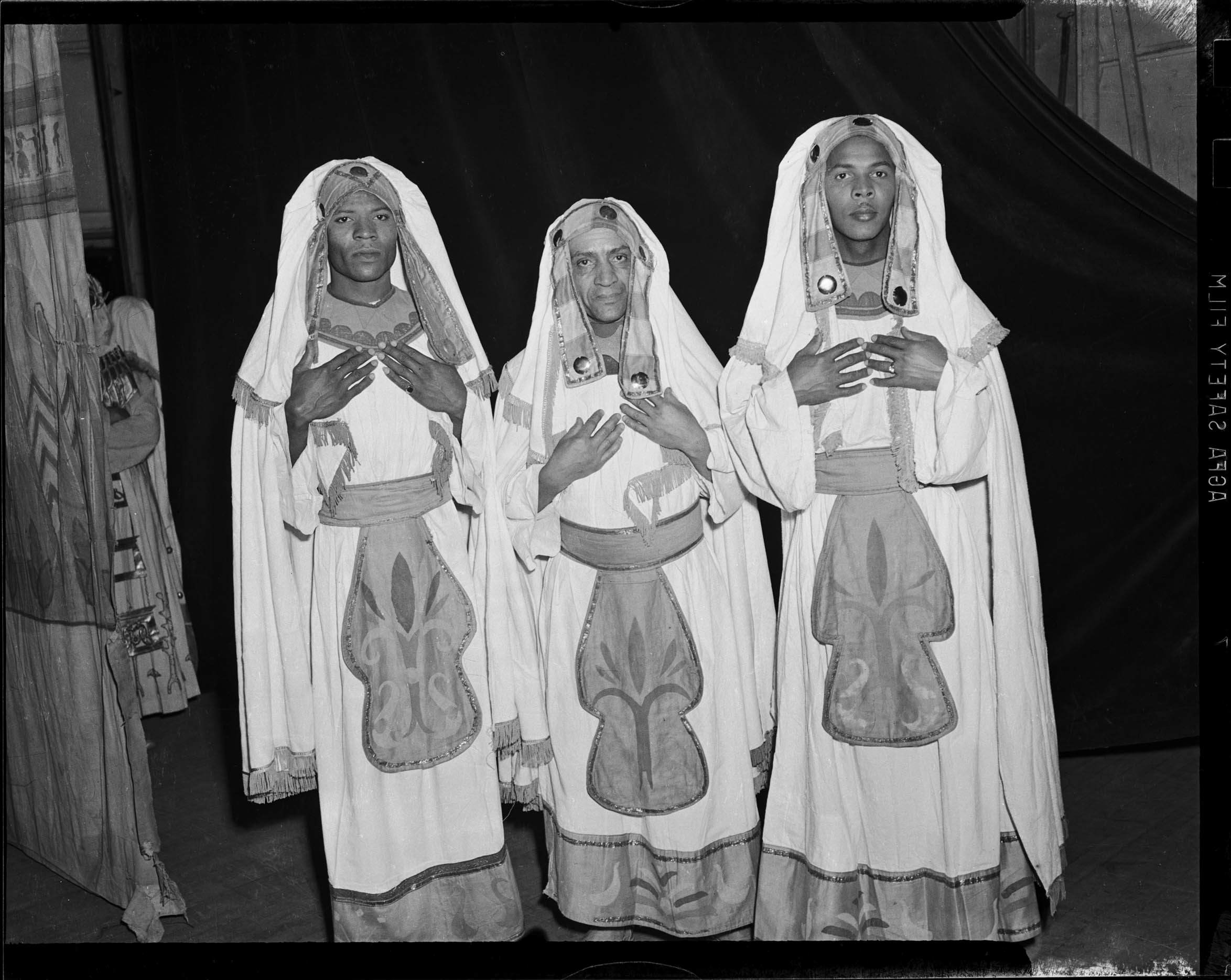

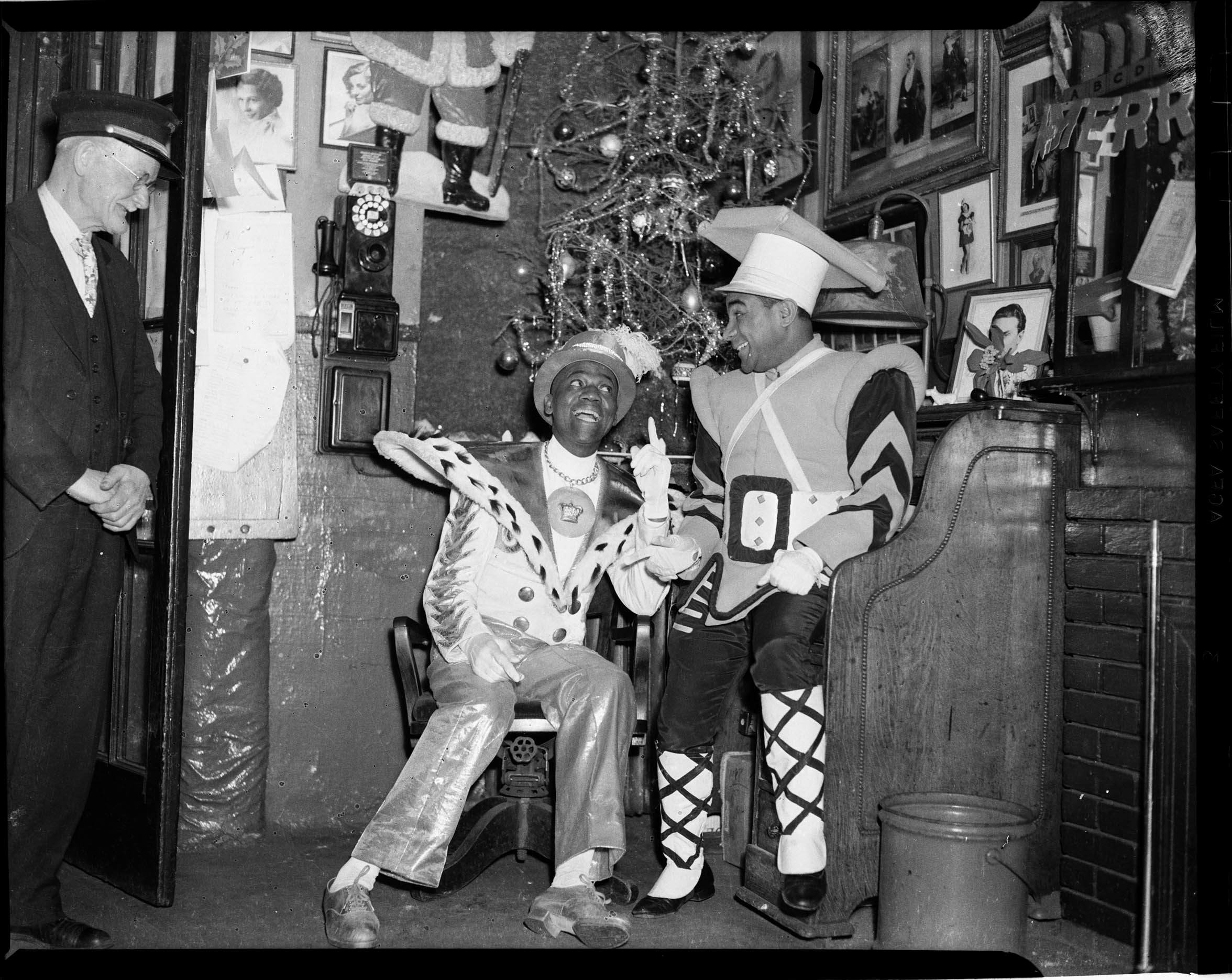

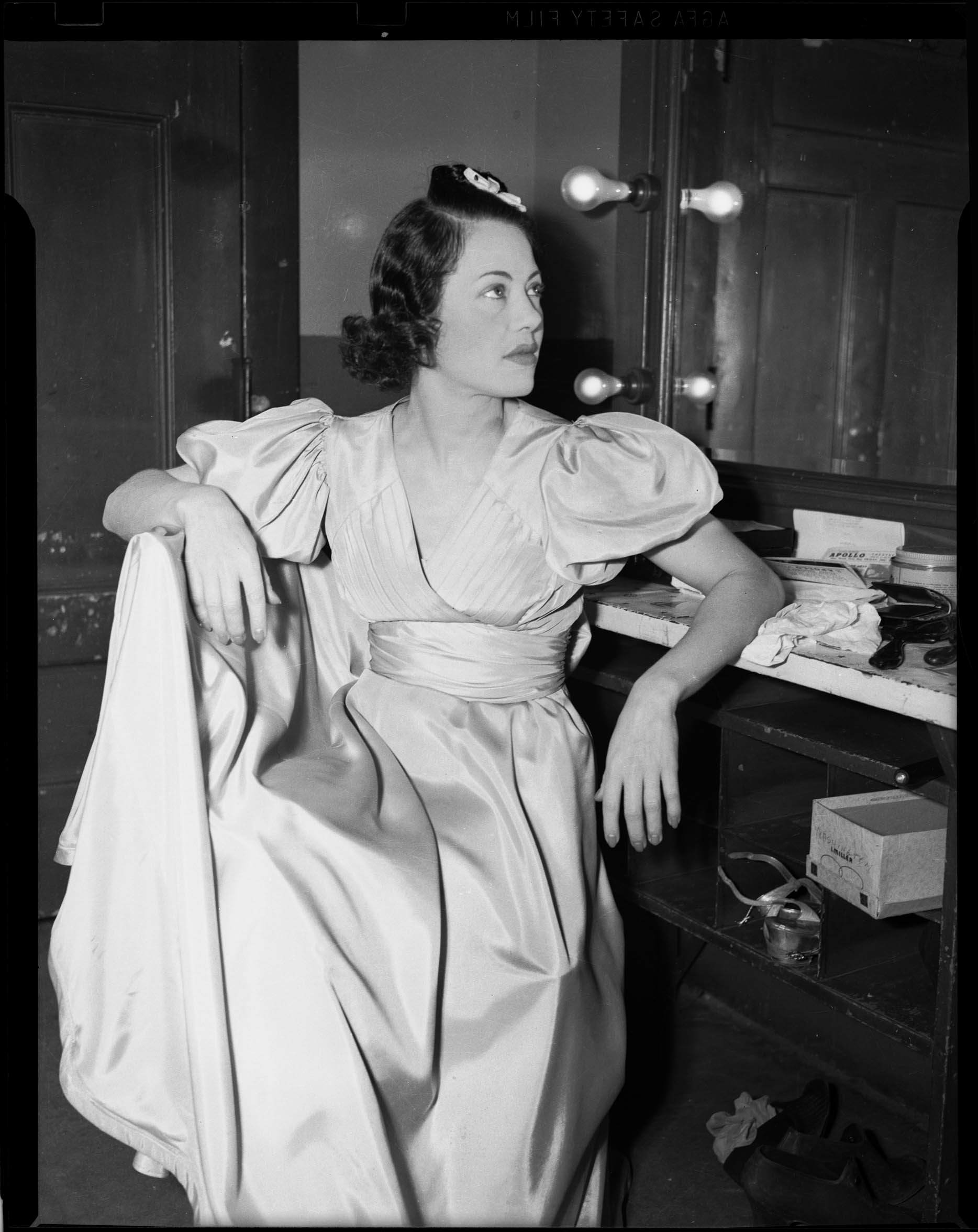

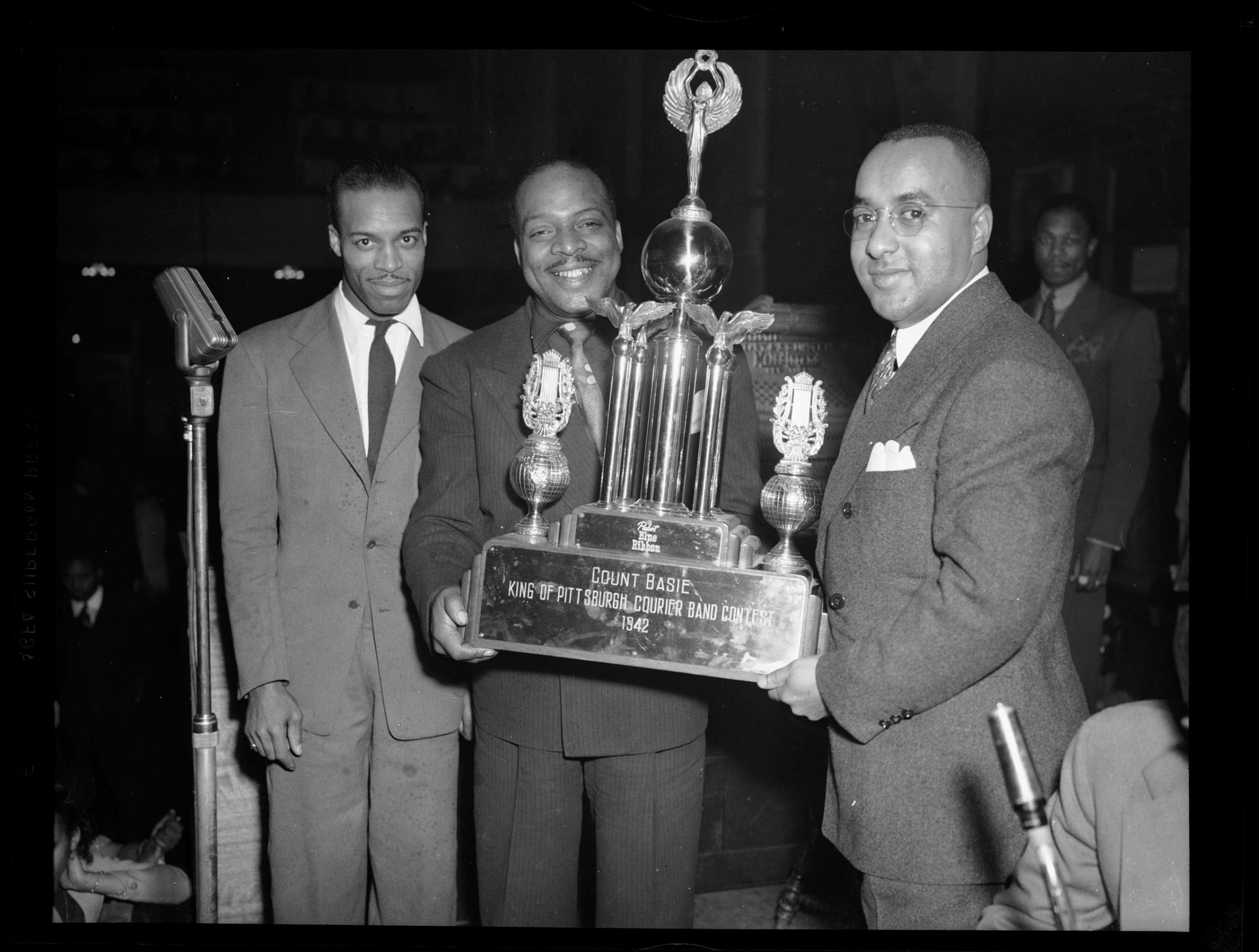

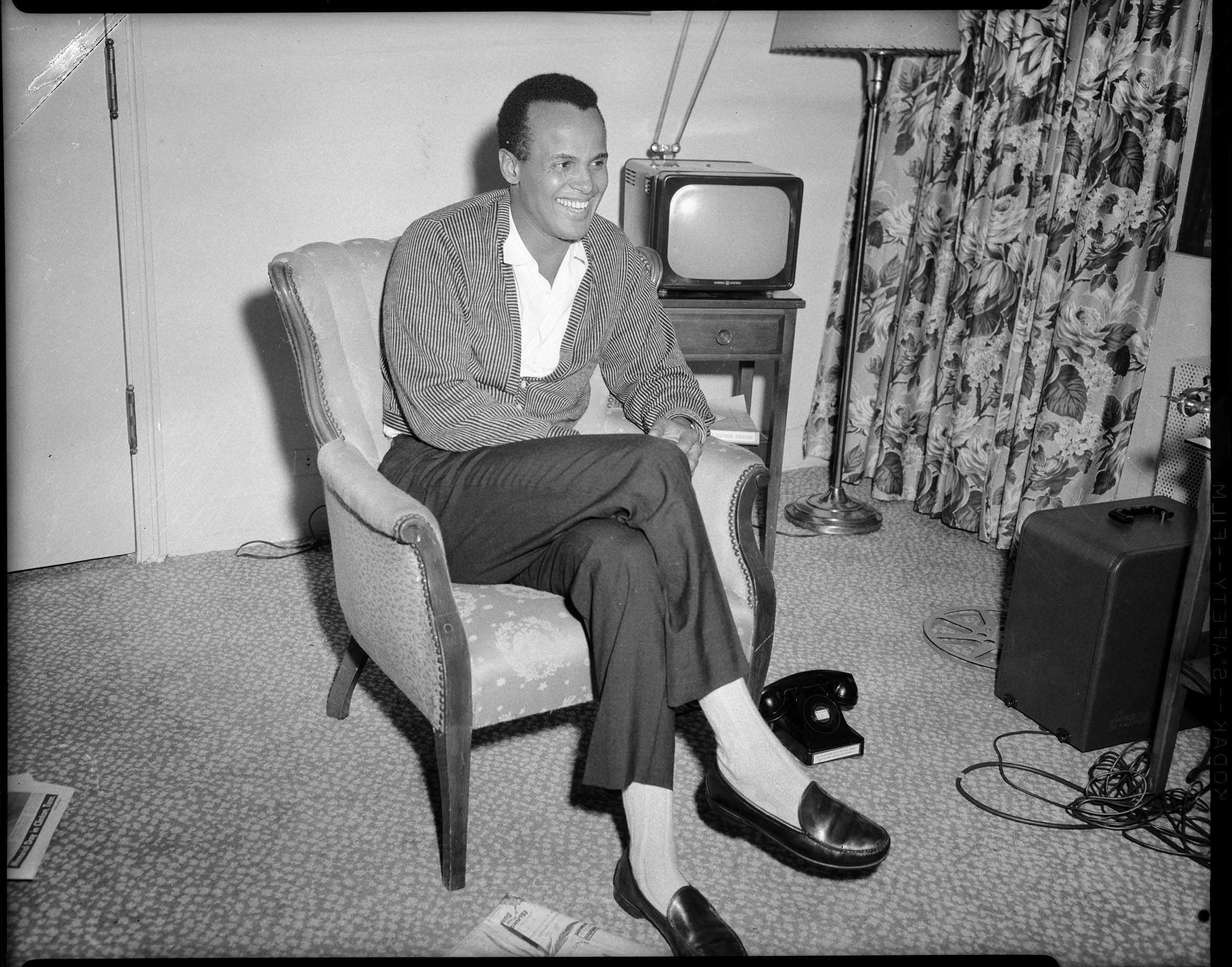

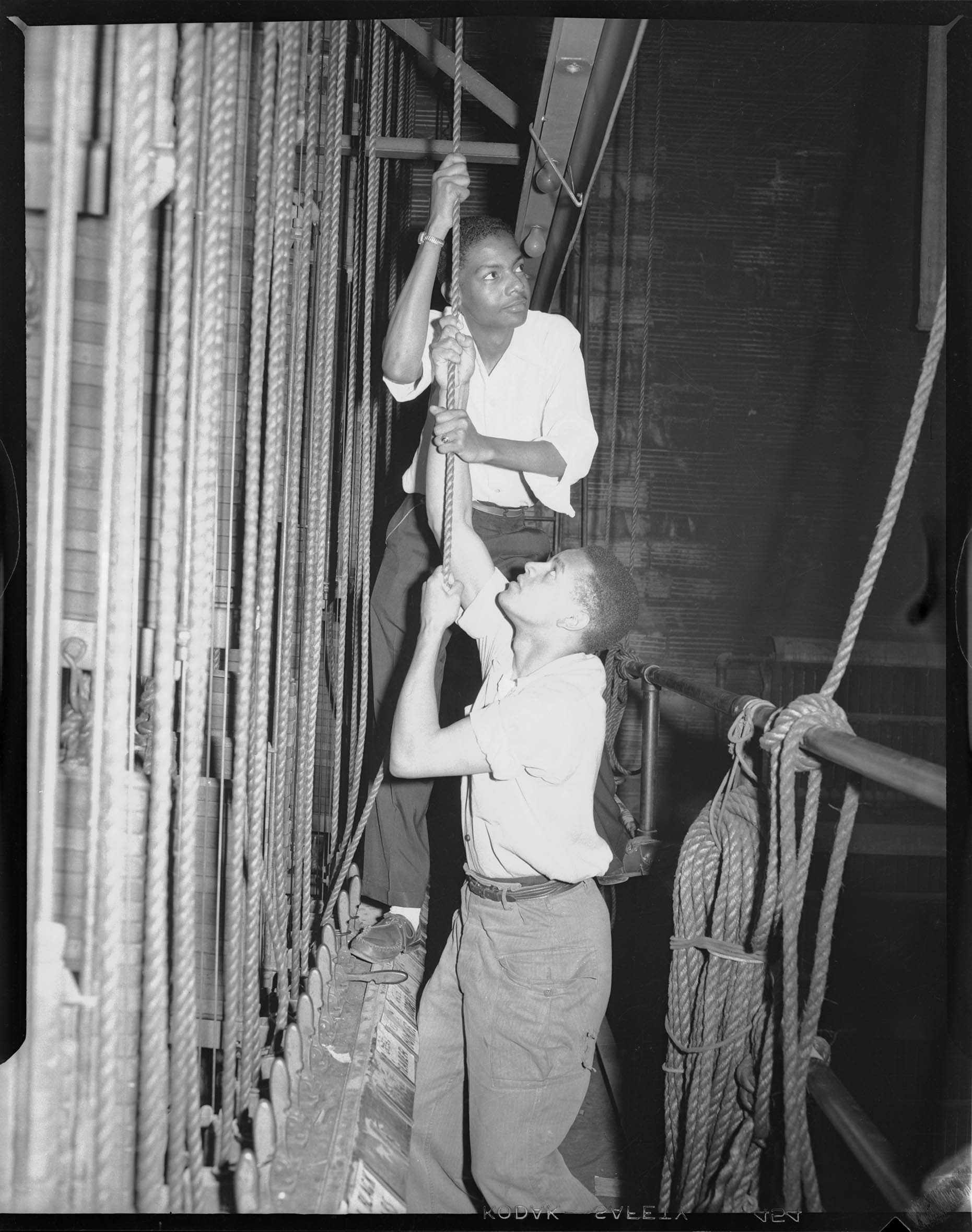

Spread across two galleries, one at the Carnegie and the other at the August Wilson for African American Culture, Great Performances is bursting at the seams with famous faces: intimate shots of Lena Horne lounging backstage and Harry Belafonte relaxing in a domestic scene; a fly-on-the-wall image of Billy Eckstine conducting an orchestra that includes Sarah Vaughan, Charlie Parker, Dizzie Gillespie, and Art Blakey; a brilliant double exposure of Nina Simone in concert. But where the exhibition soars is in the photographs of local performers — enthusiastic hoofers, singers, actors, even a magician — who were never famous beyond their living room, their family, their neighborhood, but whose joy and enthusiasm in performing is preserved in moments that, as Cheryl Finley, Associate Professor of History of Art and Visual Studies at Cornell University, writes, epitomize “an undeniable aesthetics of aspiration.”

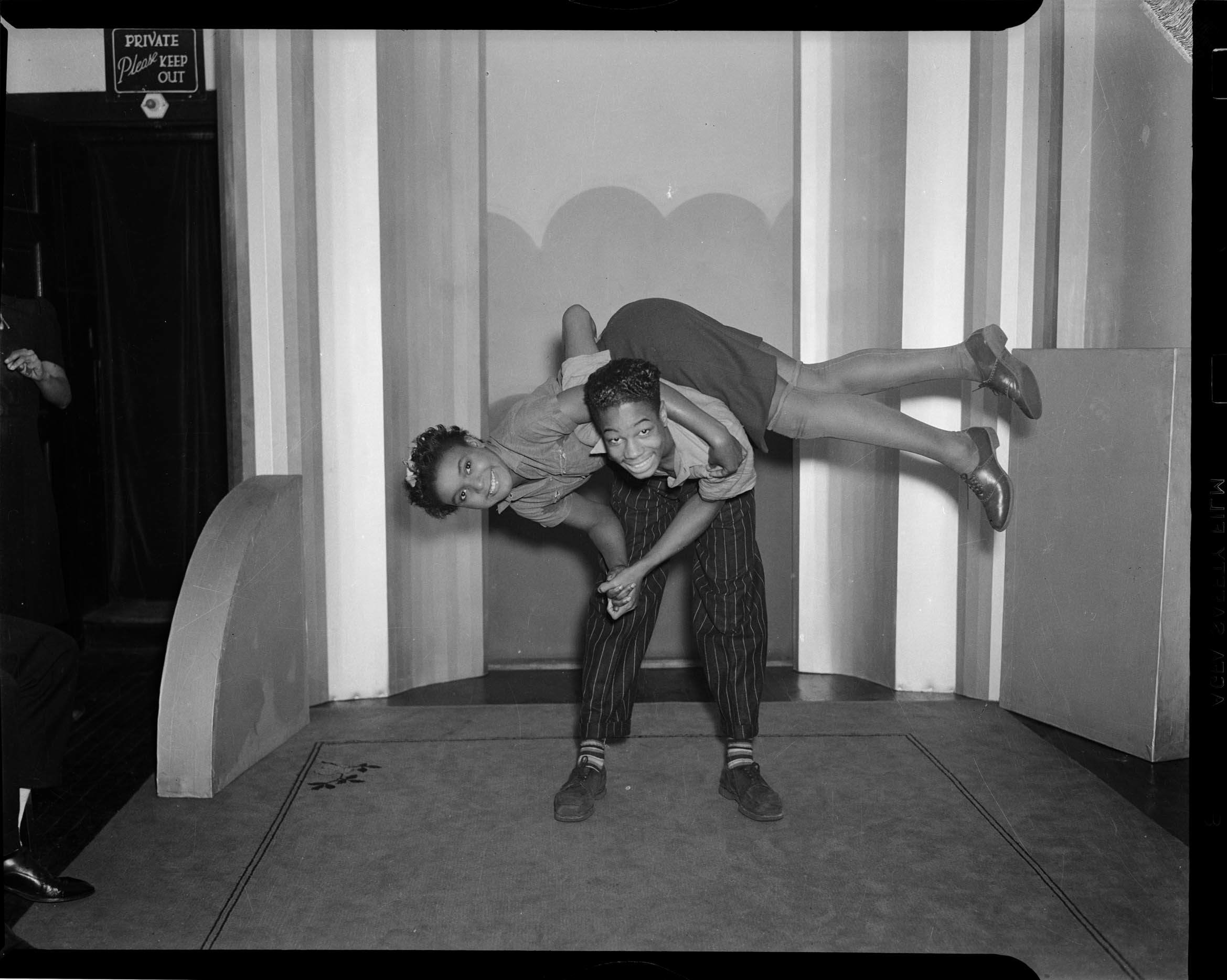

In one studio shot from 1945, a young man is hunched over, his dance partner splayed perpendicular on his back demonstrating a dance move. A staged caught-in-the-act shot, it leaps off the wall thanks to the wattage of the young dancers’ exuberant smiles. Similarly, a portrait of a young girl at her living room piano, fingers on the keys and face full of excited anticipation, is a testament to a love of music and the optimism and middle-class prosperity that was part of the postwar black community — a reality mostly ignored by white media at the time.

“Harris’s photographs provide an intimate view of twentieth-century black life, not generally known or recognized,” writes University of Pittsburgh history professor Laurence Glasco. “They show that black life encompassed more than misery and protest, and provide vivid examples of black life as a larger American story.”

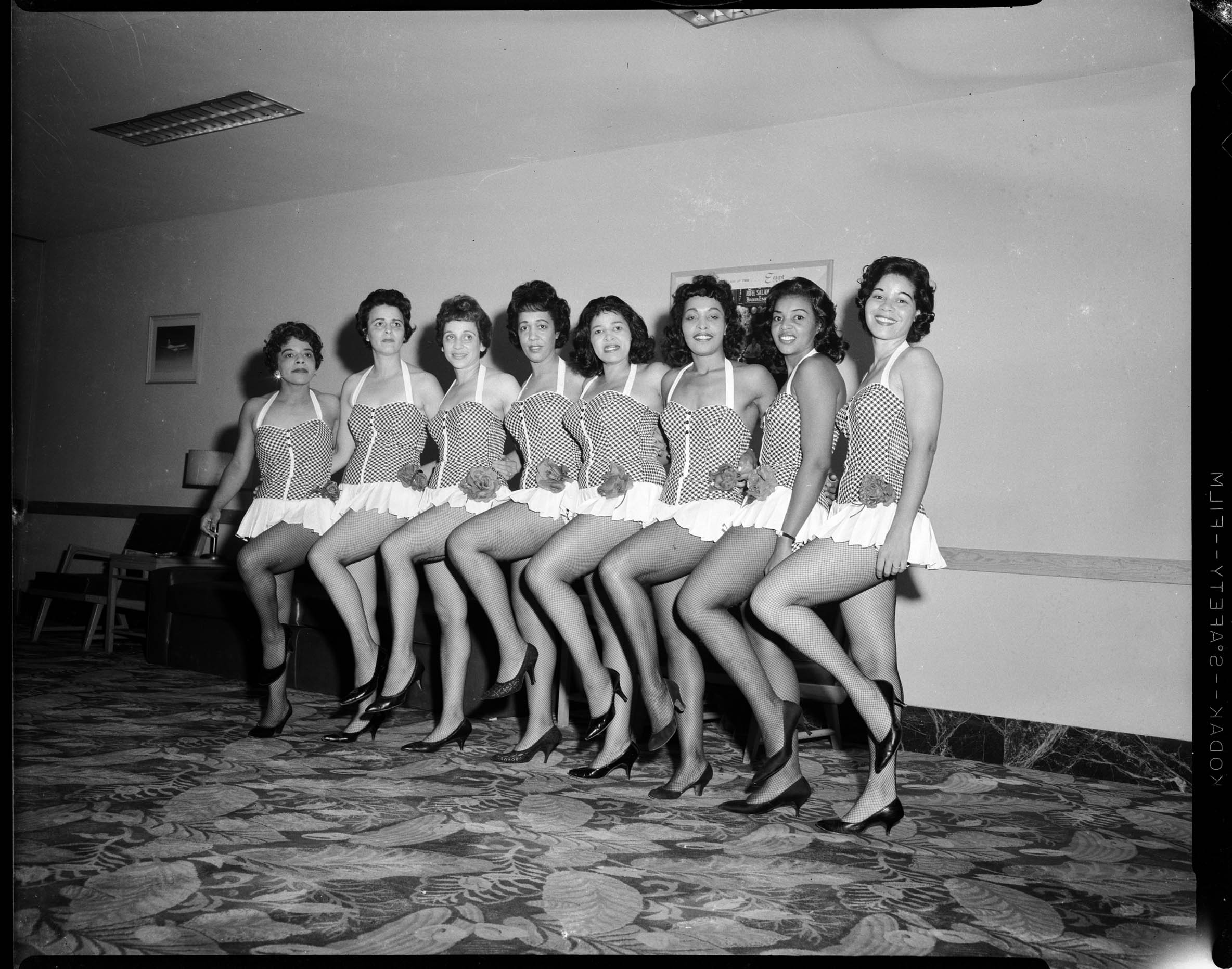

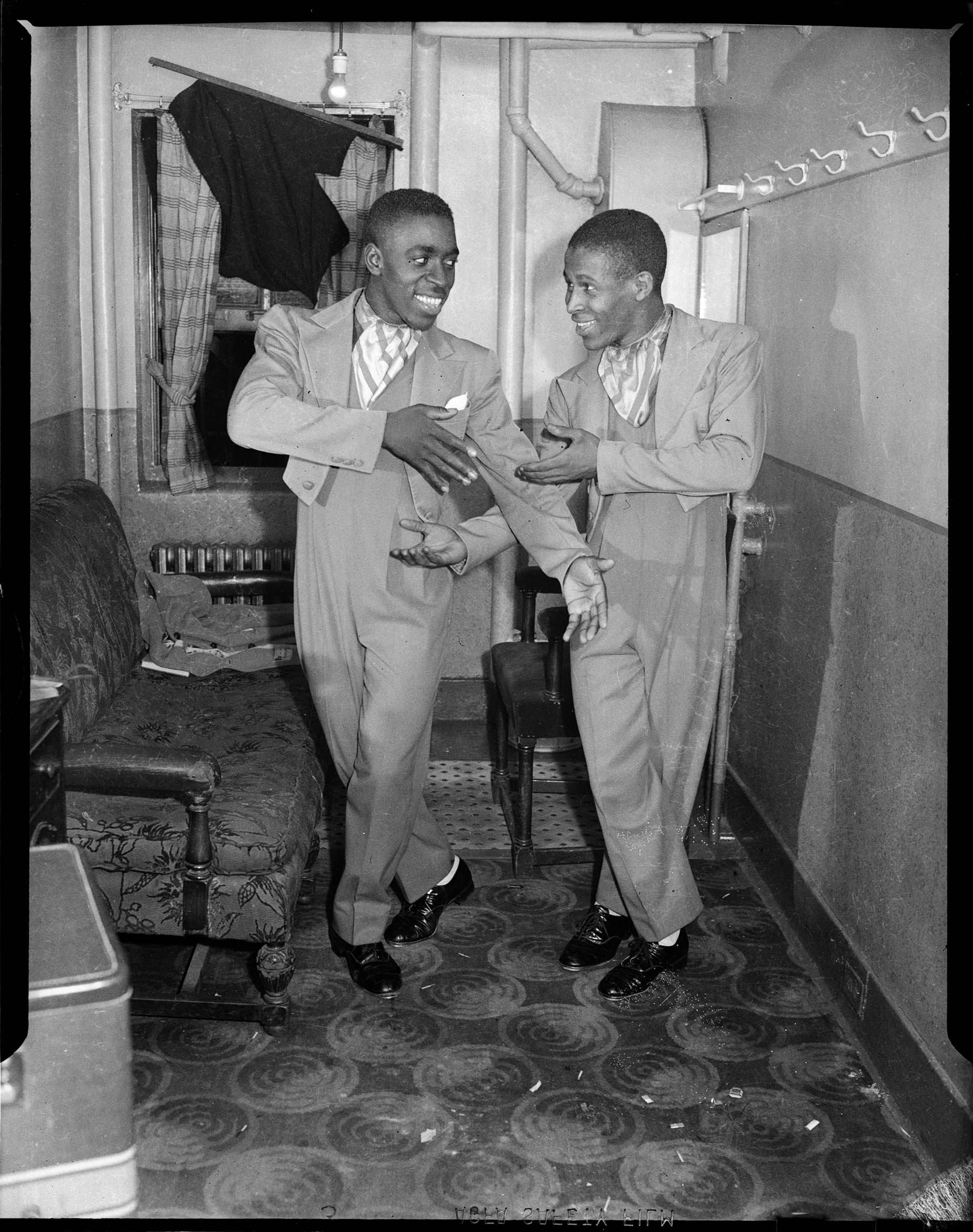

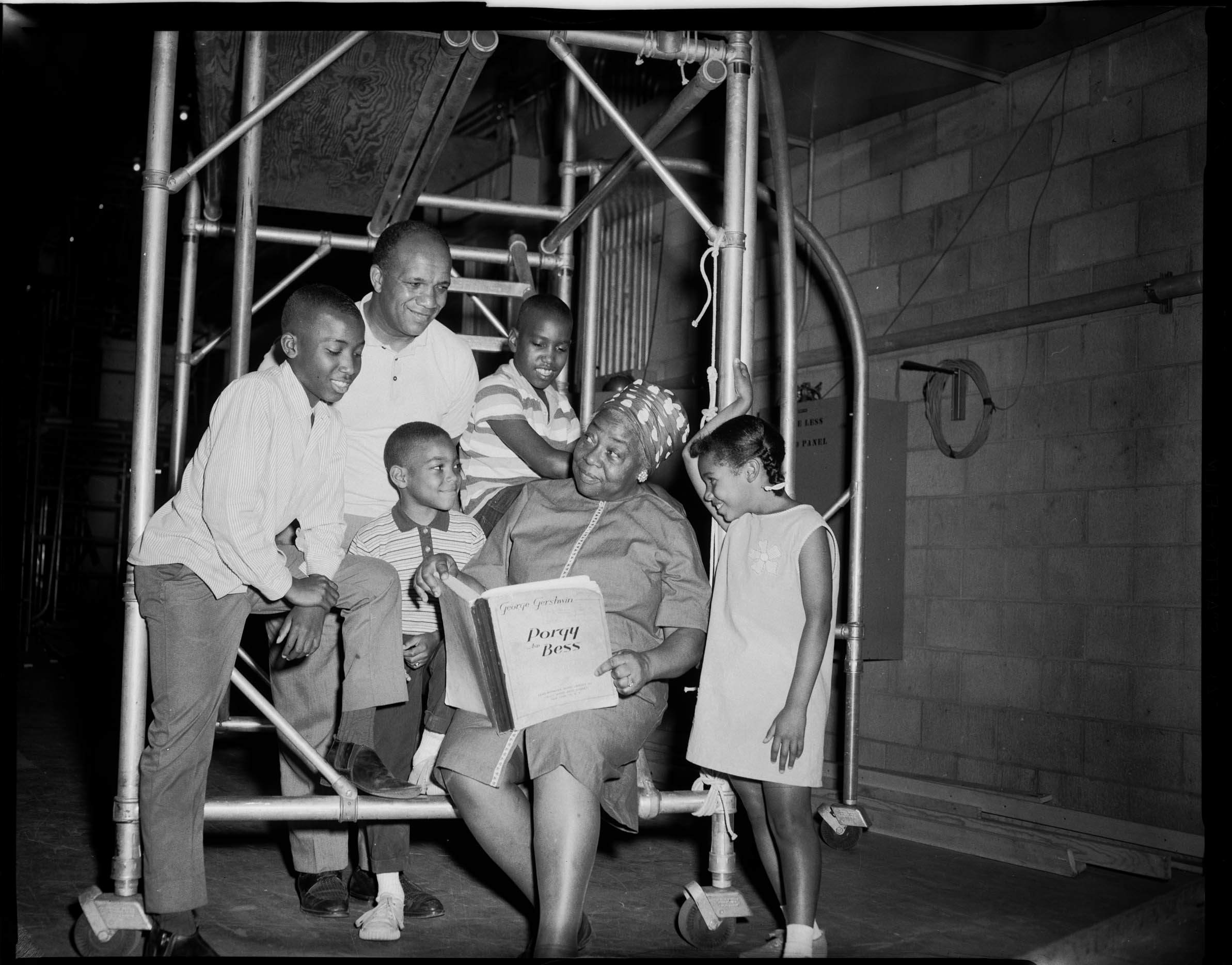

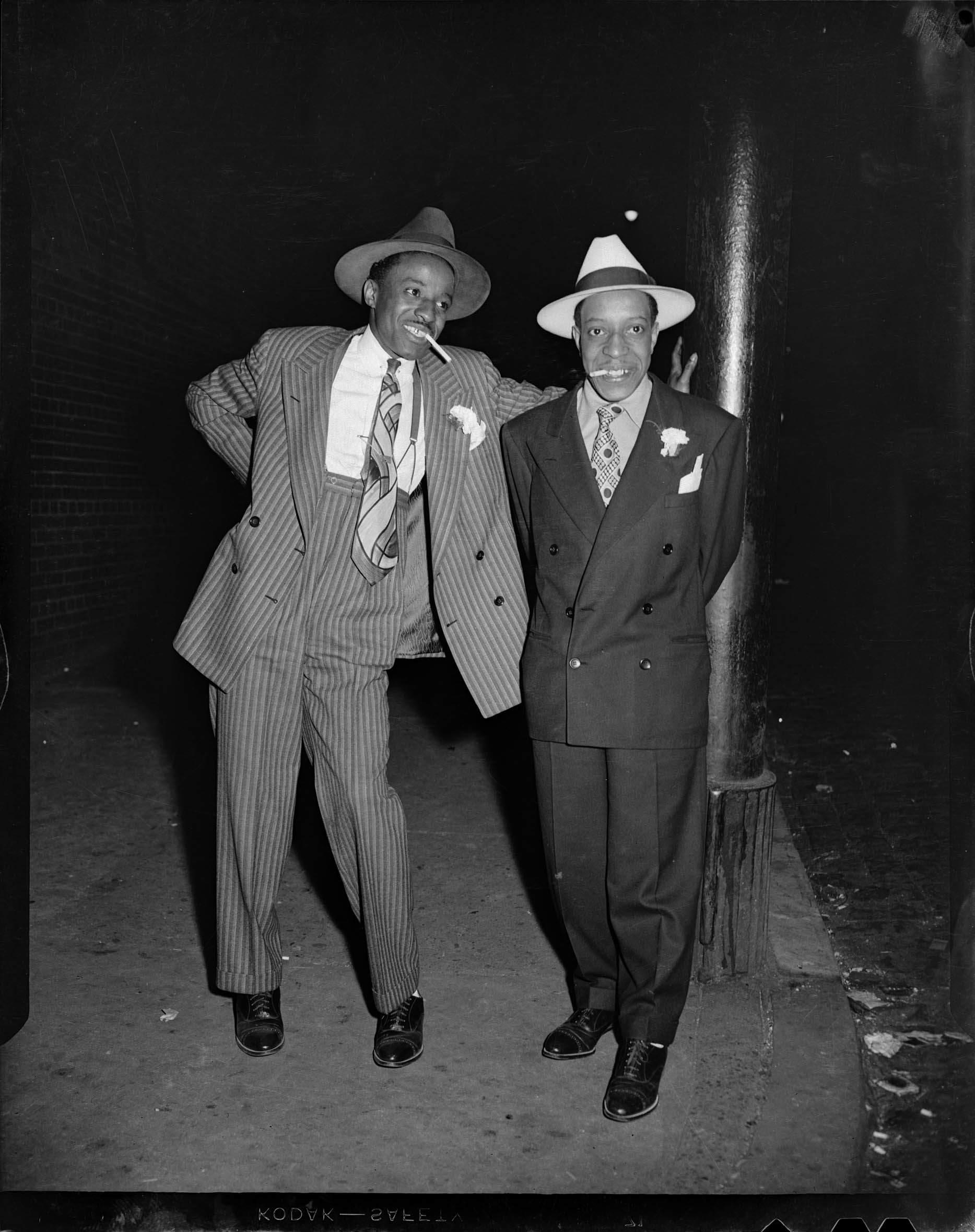

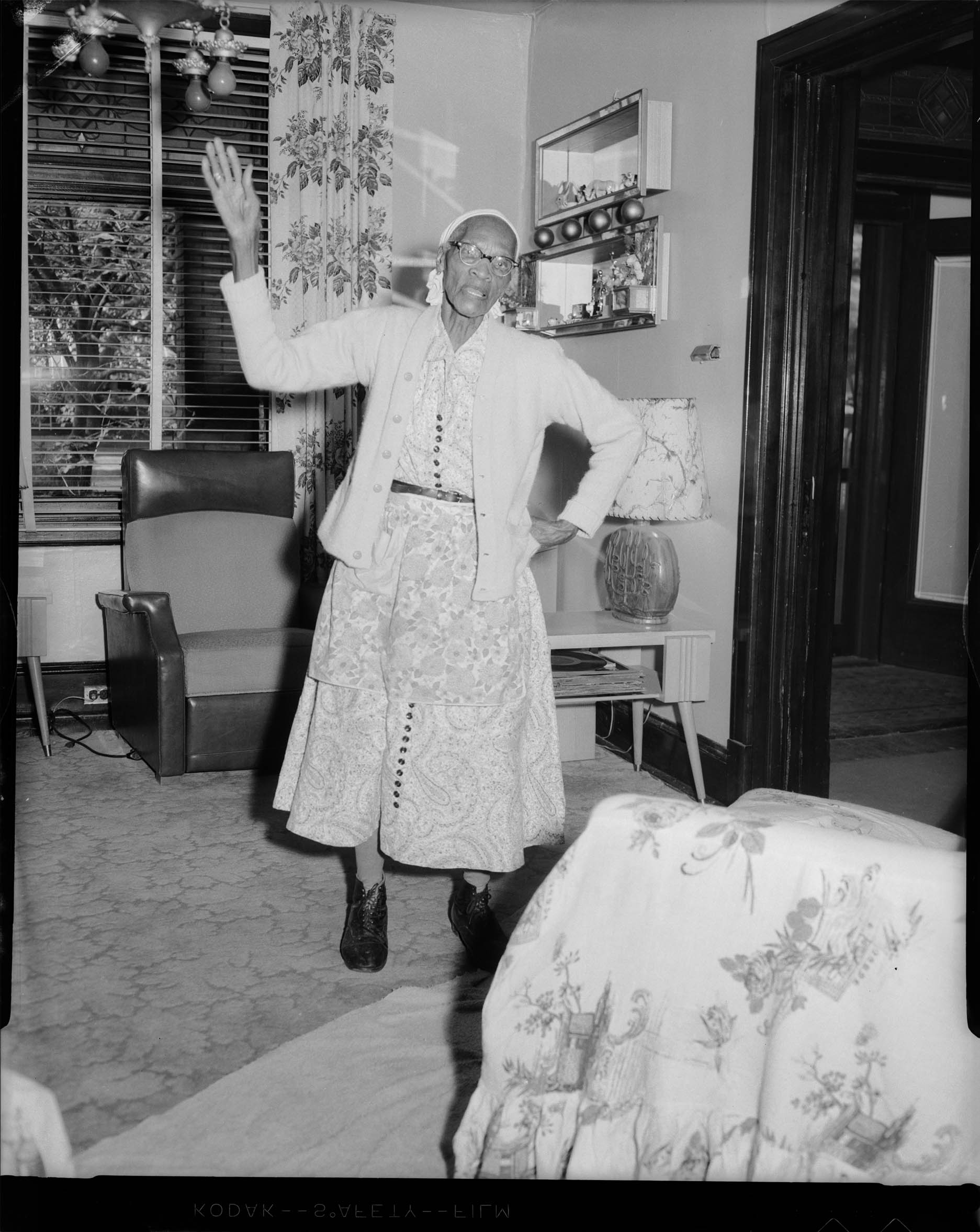

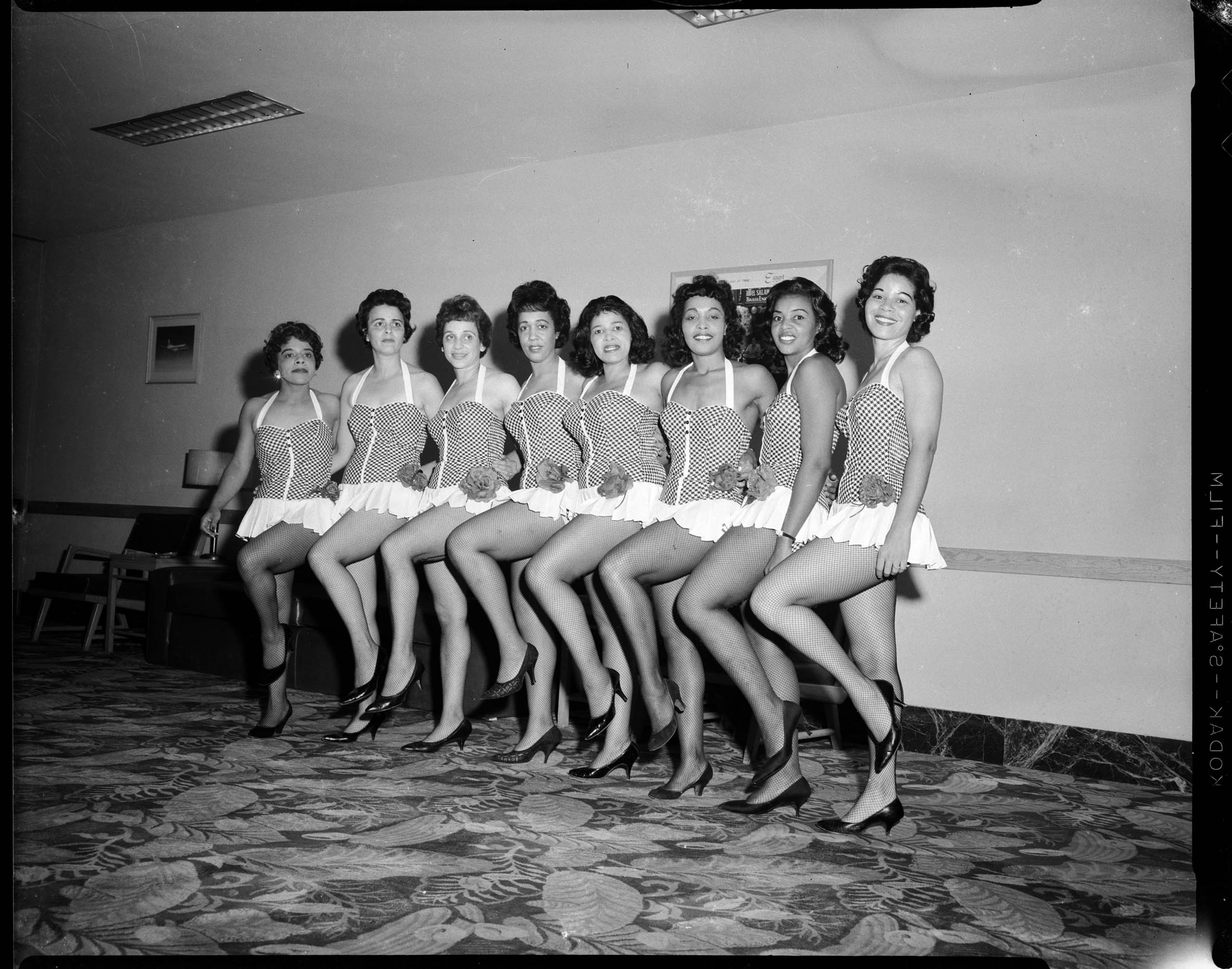

Indeed, Harris has a wide-angle view of his community. He photographed a backstage generational transmission of experience at a performance of Porgy and Bess, a “nonagenarian” dancing “the twist” alone in her living room, hep cats in zoot suits, even a kickline of young mothers in sexy dance costumes. And then there’s the charged shot of the VFW Post 46 band — all black — that celebrates the men serving their country in World War II while protesting the segregation they face despite the uniform.

But more importantly, he documented — honestly — culture that would be considered transgressive by any community at the time. One of the most arresting images in the show is of four cross-dressers performing in 1952. In the conformist 1950s, no one would dare publish a photograph of four men in drag, faces caked in makeup and muscular arms and legs proudly bared — especially not when transmitting the wrong skin color was dangerous enough on its own. And, indeed, it seems to have been taken for posterity or otherwise consigned to the archive. But Harris got the shot. Multiple, actually; he took at least a dozen similar photos in this period. This is confirmation not only of the unflinching trust his subjects had in him as a neighborhood insider disinterested in exploitation, but also the scope of Harris’ vision in creating a vibrant, complete record of a community and people that resonated beyond the local black experience.

“Harris’s photographs have that special local-global yin and yang,” Finley writes. “That is, their focus is black Pittsburgh, but the stories that they tell and the lessons that they teach have universal appeal for African Americans, and perhaps all Americans.”

These are monuments of love and creation, not crime and destruction, and so were mostly hidden from white audiences. That’s a cultural tragedy. The everyday people immortalized in Harris’ work are a tribute to the power of performance to instill pride and self-worth even in the face of crushing discrimination. And the photos themselves exist as a parallel history of popular American entertainment — how much was accomplished and far we still need to go, not only to diversify representation in media but to simply acknowledge the legacy long kept of view.

Teenie Harris Photographs: Great Performances, guest curated by actor Bill Nunn, is on at the Carnegie Museum of Art is on until July 17.

Dante A. Ciampaglia is a writer and a senior digital editor at Sports Illustrated Kids. Follow on him Twitter @daciampaglia.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com