Correction appended: May 13, 2016.

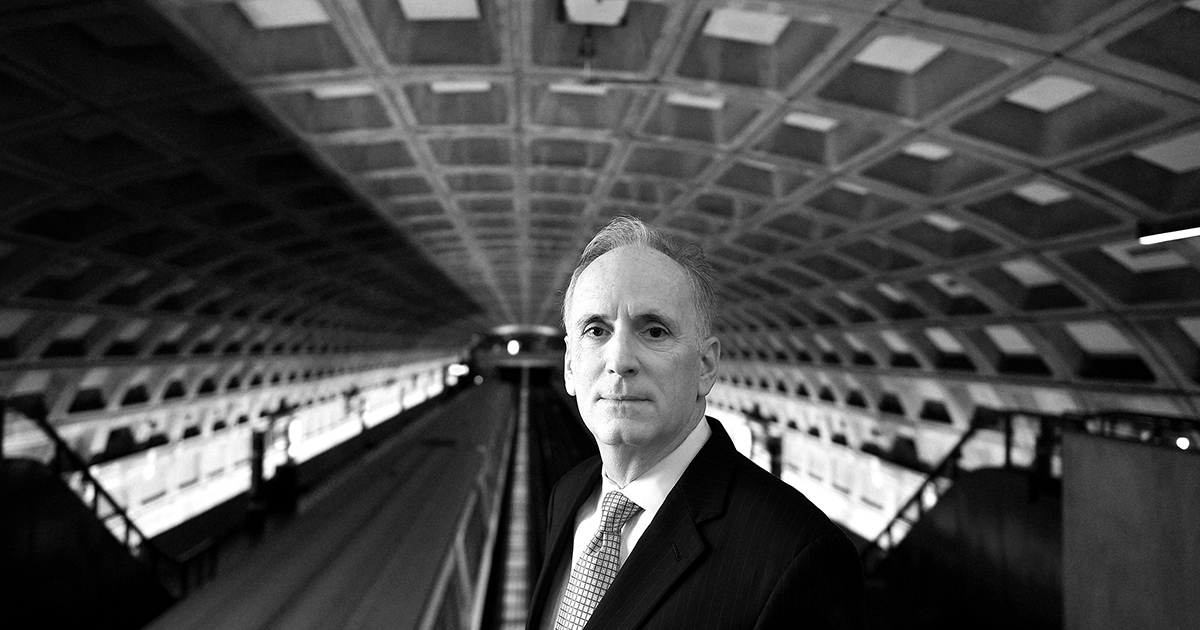

Paul Wiedefeld knew Metro was a mess before he agreed to become its CEO. But it wasn’t until about a month into the job that he grasped the scale of the problems at Washington’s troubled transit agency. One morning late last year, he ducked into D.C.’s Union Station for a short ride to work. Nothing catastrophic had happened: there were no plumes of smoke nor any fireballs, both of which have been known to mar Metro commutes.

But a minor railcar shortage had slowed the Red Line to a crawl, and the platforms were crammed–a sight so familiar that the station manager barely reacted. Wiedefeld, however, was stunned. “I blew a gasket,” he recalls, sitting in his downtown office at a conference table plastered with transit maps. “This organization has become numb.”

These days the capital’s 118-mile (190 km) rail system makes Capitol Hill look competent by comparison. Metro is beset by chronic delays and frequent breakdowns. Its finances are in tatters. Riders are fleeing in frustration. Everything from the tracks and the trains to the signals and the switches have slipped into disrepair, sparking increasingly frequent fires and threats from federal regulators to shutter the system. Ten riders have died in two incidents caused by mechanical problems since 2009.

For decades, leaders of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority sought to address these issues but instead merely managed the agency’s decline. Wiedefeld, 60, is bringing a bolder approach. When a tunnel fire broke out in March, the hard-charging boss ordered the entire system to close–on a Wednesday, with less than 24 hours’ notice–disrupting the movement of hundreds of thousands of daily customers, including much of the federal workforce. On May 6, he announced a massive yearlong maintenance overhaul that will cripple commutes, challenge employers and hobble businesses.

Wiedefeld knows he’s testing the region’s tolerance. But in a city that’s famous for dysfunction, he’s betting that customers and voters will accept a little bit more of it–at least for a while–if it begins to fix Metro’s problems. “We cannot go on the way we’ve been managing this system,” he explains. “That’s not what I came to do.”

The stakes are bigger than Metro’s survival. If he succeeds, Wiedefeld could chart a new path for officials who are struggling to overcome sluggish bureaucracies and improve the nation’s decaying infrastructure. Across the country, roads, bridges and dams are crumbling. In a 2013 report card, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave U.S. infrastructure a D+ grade and called for $3.6 trillion in investment by 2020. The consequences of delaying hard choices are evident from the pipes of Flint, Mich., to the levees of New Orleans to the fatal collapse of a Minneapolis bridge in 2007. Cash-strapped local governments have created long-term problems by dodging short-term challenges.

“What’s happened in the Washington Metro has happened, in one form or another, to most of the infrastructure in the U.S.,” says Richard Ravitch, who led the successful turnaround of the graffiti-scarred New York City subway in the 1980s. Which is why leaders are watching Wiedefeld’s Metro experiment with interest. If the new boss can fix the nation’s worst transit system, D.C. could find itself in an unlikely role: example to emulate.

When it opened in 1976, Metro was a symbol of Washington’s ambitions, a subterranean monument to match the marble temples on the National Mall. The trains were new and punctual. The stations were cool and clean, with striking architectural flourishes. Expansion proved to be an economic engine, revitalizing neighborhoods and linking the suburbs to the city’s downtown core. “It was a pretty happy system up through the late 1990s,” says Zachary Schrag, a history professor at George Mason University in Virginia and the author of a book about Metro.

Yet from the start, Metro was saddled with two structural flaws. First, each line runs on just two tracks–New York City’s subway generally has four–which makes it difficult to perform maintenance while still shuttling commuters. And though Metro needs $3 billion per year to operate, it is the only major U.S. transit system without its own dedicated revenue stream, like a specific tax.

As a result, Metro has to wheedle hundreds of millions of dollars each year out of a patchwork of jurisdictions–the District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia and the federal government–whose politicians have limited cash and competing priorities. “Metro is an institutional orphan,” says Richard White, acting CEO of the American Public Transportation Association, who ran Metro for a decade. “When it came time to take care of what needed to be done to keep things in order, everybody headed for cover.”

As far back as the early 1990s, Metro’s boss was warning that the organization would face future peril without the funding to embark on a major rebuilding project. That midlife upkeep never happened. By 2004, White declared that the system was falling into a “death spiral.”

Events proved him right. “The ideal thing would be to rebuild the entire system from scratch,” says Jack Evans, a D.C. city councilman and the chairman of Metro’s board of directors. Evans recently jolted the region’s residents by suggesting that entire lines could be closed for months. At a congressional hearing in April, he demanded that the feds pony up some $300 million a year to help forestall future safety calamities. “Next time something happens, I’m blaming you guys,” Evans said, wagging a finger. Florida Representative John Mica, a Republican, shot back that federal taxpayers wouldn’t bail out “the most screwed-up mess I’ve ever seen in business or government.”

Wiedefeld has forged ahead. His sprawling overhaul, which begins on June 4, will shut down sections of track and snarl huge swaths of the system to catch up on critical maintenance. There are tens of thousands of old wooden rail ties to swap out, fasteners to replace and aging insulators that keep sparking. Sleeves on power cables are missing or dangerously eroded by leaks in the tunnels. Some of the original 1976 trains are still in use; new ones are buggy.

There is also the problem of workplace culture, as seen in the impassive reaction of that Red Line station manager. At a May 3 hearing into a 2015 smoke incident that killed one rider and sickened dozens, a National Transportation Safety Board member studied a litany of equipment malfunctions and operator mistakes and declared that Metro has “a severe learning disability.” Ask Wiedefeld what keeps him up at night, and he replies, “What hour?”

A Baltimore native from a blue collar family, Wiedefeld now makes $397,500 running Metro. He’s “one of the most capable and effective leaders with whom I’ve ever worked,” says former Maryland governor Martin O’Malley, who hired him in 2007 to run the state’s transportation authority. Wiedefeld served two stints as the CEO of Baltimore Washington International Airport, where he boosted international traffic, built a new terminal that serves as a hub for Southwest Airlines and distinguished himself as a hands-on manager. “I am a bit of a taskmaster,” he says.

So far the new boss has won accolades for making decisive moves. But Wiedefeld is still in the grace period before the incoming executive can be blamed for not solving the problems he inherited. And Wiedefeld knows that goodwill can quickly evaporate once he starts disrupting the commutes of hundreds of thousands of people per day. “This is 30 years in the making,” he says. “People’s patience is gone.”

At the heart of the challenge is an equation that nobody has solved: how to balance complex variables like safety and convenience, and economics and efficiency, all while convincing politicians with more immediate priorities that they should forgo popular programs to invest in the unsexy realm of infrastructure. “They are always going to go back to their self-interest,” Wiedefeld says.

That goes for his employees as well. On a drizzly May morning, Wiedefeld summoned some 650 senior managers for a state-of-the-organization meeting at a concert hall in suburban Maryland. It was the first such gathering in Metro’s 40-year history, and one of the first orders of business was explaining to the staff why he had written a memo warning that they could all be fired. “I’m certain many of you thought, What a jerk,” Wiedefeld said. Which may be what Metro needs.

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the full name of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Alex Altman at alex_altman@timemagazine.com