In recent weeks, some members of Congress have expressed alarm that the U.S. Merchant Marine is shrinking to a point that America would not be able to find enough cargo ships and merchant mariners to supply American troops in a distant war zone for longer than a few months. “We are very close to not having enough mariners,” Administrator Paul N. Jaenichen of the U.S. Maritime Administration told a House subcommittee during a hearing in March. In response, Rep. Rob Wittman of Virginia acknowledged that the situation is “a strategic disaster in the making.”

Exactly how to maintain a healthy Merchant Marine for international trade is a complex question. U.S. flagged ships are more expensive to operate than ships from many foreign countries, which pay lower wages and are subject to fewer regulatory and legal requirements. In order to be competitive, U.S. flagged merchant ships need government subsidies and a steady flow of guaranteed cargo. As a result, the U.S. Merchant Marine is a relatively small player in global trade. But the need for a viable U.S. merchant fleet — a force of civilian mariners to haul vital military cargo overseas in a national emergency — is not really in doubt.

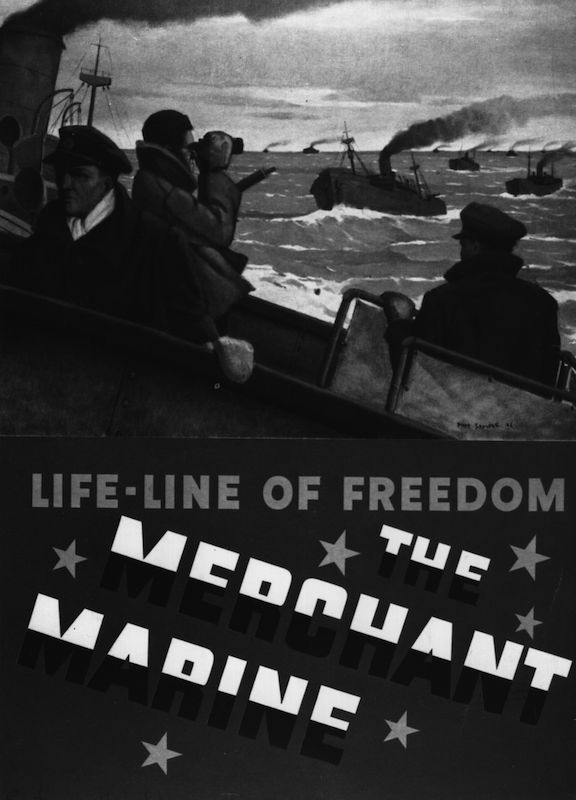

The Merchant Marine has played a critical role in every major American military conflict since the Revolution. Never did it play a greater role than in World War II, and a glance back at what happened then offers some perspective for the debate today.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Even before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, American merchant mariners on freighters and tankers flying the U.S. flag were risking their lives to carry arms, ammunition and food to keep the British in the fight. When America formally entered the war, German U-boats invaded U.S. waters to cut off the supply line at its source. They sank American cargo ships within sight of tourist beaches in Virginia and Florida, and at the mouth of the Mississippi River. They torpedoed ships and killed mariners in the Arctic, the South Atlantic, the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico and the Mediterranean. They sank hundreds of vessels, killed more than 9,000 American merchant mariners, and sent tons of vital supplies to the sea bottom.

The U.S. military was unprepared for the U-boat onslaught, and for much of 1942 it lacked the ships, planes and, sadly, the inclination to protect the cargo ships. Again and again merchant mariners were sent on hazardous voyages with no protection, in the hope they would be lucky enough not to encounter a U-boat. The result was a slaughter that the government did its best to downplay and conceal from the public.

But there was no concealing it from communities such as Mathews County, Va., a tiny outpost of seafarers on the Chesapeake Bay. Twenty-three Mathews mariners were killed, and several times as many narrowly survived torpedo explosions, fires, icy water, shark attacks, flaming oil slicks and harrowing odysseys in lifeboats and on rafts. Many survived sinkings and then went right back to sea to run the same perilous gauntlet. One Mathews sea captain survived two torpedo attacks only to be killed in a third while riding home to Mathews as a passenger on another ship. Another torpedoed Mathews captain’s remains were found in the belly of a shark caught by fishermen not far from where his ship sank.

MORE: Tuskegee Airman Reflects on Service Ahead of Iconic Fighter Plane’s Restoration

The Mathews men and their fellow merchant mariners, who were exempted from the draft as long as they kept sailing, might have just said, “To hell with this,” and taken draft-exempt jobs in shipyards, but they stayed on ships. One Mathews mariner whose legs were horribly mangled by a torpedo explosion browbeat his union reps and his shipping company to let him go back to sea before the war ended. Merchant mariners continued to carry the goods while the tide of the war finally turned, the Navy set up convoys to protect the merchant ships, and the Allies figured out how to defeat the U-boats. Then the Merchant Marine, reinforced with thousands of new vessels churned out by American shipyards, delivered the troops and supplies for the great invasions that liberated Europe from the Nazis. No Allied army was ever driven back from a hard-won beachhead for lack of supplies.

After peace was declared, the mariners continued to sail, bringing home the victorious troops and, on the return trips, carrying material to Europe to rebuild the nations shattered by the war. The mariners even brought home the American dead whose families wanted them reburied in U.S. soil.

But after the war, the mariners were pretty much forgotten. Their vocal supporter, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, died before the war ended, and Congress did not heed his request that they be provided for. Merchant mariners were left out of the G.I. Bill and other government benefits. They were also largely left out of the history books, omitted from the American narrative of How We Won the War.

Efforts in Congress to belatedly honor them— by granting them veterans status or writing checks to the relative few of the old mariners who are still alive—never seem to gain any political traction. One frequent argument against further compensating them is that they made plenty of money through bonuses for sailing in war zones and hauling hazardous cargo. But detailed studies have shown that merchant mariners were paid no better than their counterparts in the armed forces. All those arguments soon will be moot; the World War II mariners are in their late 80s and 90s.

But their contributions to the Allied victory in World War II stand. And that history might be worth considering at some point in the debate over what is to become of the Merchant Marine in the 21st century.

William Geroux is the author of The Mathews Men: Seven Brothers and the War Against Hitler’s U-boats, published April 19 by Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com