On Feb. 11, Kanye West threw himself a party at Madison Square Garden, partly to hype the new season of his Yeezy clothing line but also to unveil The Life of Pablo, the album he’d been dangling in front of fans since 2014. While models stood still in the center of the arena, dressed in clothes that looked ripped from a postapocalyptic thriller, West played new songs off a laptop like he was deejaying New York’s biggest house party.

West had long been tinkering with his new music, changing the title from So Help Me God to Swish and then Waves. He’d also been amending the track list, which began with 10 songs, and sharing it on social media. When he debuted the music in front of thousands at the Garden–plus 20 million or so watching the live stream–fans thought they had finally heard what The Life of Pablo was all about.

Kanye had other ideas.

One day later, he tweeted that he was adding more songs. Two days later, he performed on Saturday Night Live. On the third day, Pablo rose again, appearing in the wee hours on the streaming service Tidal, which West co-owns. Now it had 18 tracks, and in the next 10 days it would be played 250 million times, Tidal said.

But Kanye wasn’t done yet.

That afternoon, he tweeted, “Ima fix wolves” and over the next few weeks he proceeded to change mixes, lyrics and even the guest list. When he first premiered the track in 2015, “Wolves” showcased pop diva Sia and the rapper Vic Mensa; at the Garden, “Wolves” featured R&B singer Frank Ocean; now the first version had been restored.

Some might call this rollout a mess; West calls it innovation. On April 1, his label announced that The Life of Pablo–now at 19 tracks–is a “living” album with “new iterations” due in coming months. It was added to Spotify and Apple Music, and as a result it is now the first album to reach No. 1 on the Billboard 200 from streaming–70% of its “sales” units were actually streams.

Industry pundits have long foretold the death of the album as file sharing and the digital-music revolution drove a 57% drop in sales and licensing revenue from 1999 to 2009. (Adele, who sold 3.38 million copies of her album 25 in its first week, knows those proclamations are slightly premature.) But West isn’t alone in dismantling conventions about how a major artist releases an album–or what makes an album in the first place. While his peers explore the opportunities allowed by digital distribution, West has zeroed in on what streaming offers that other formats can’t: that the album you love today won’t be the same tomorrow.

The album as we know it is old enough to retire. Back in 1948, Columbia Records released the first successful 12-in., 331/3-r.p.m. vinyl record, nearly quintupling the amount of audio per side to around 22 minutes. (Before that, an “album” referred to a bundle of 10-in., 78-r.p.m. discs packaged together in paper sleeves.) Over the next few decades, the industry shifted focus from singles to albums, with artists following a rigorous pattern: record an album, promote it with a single, tour after release, repeat.

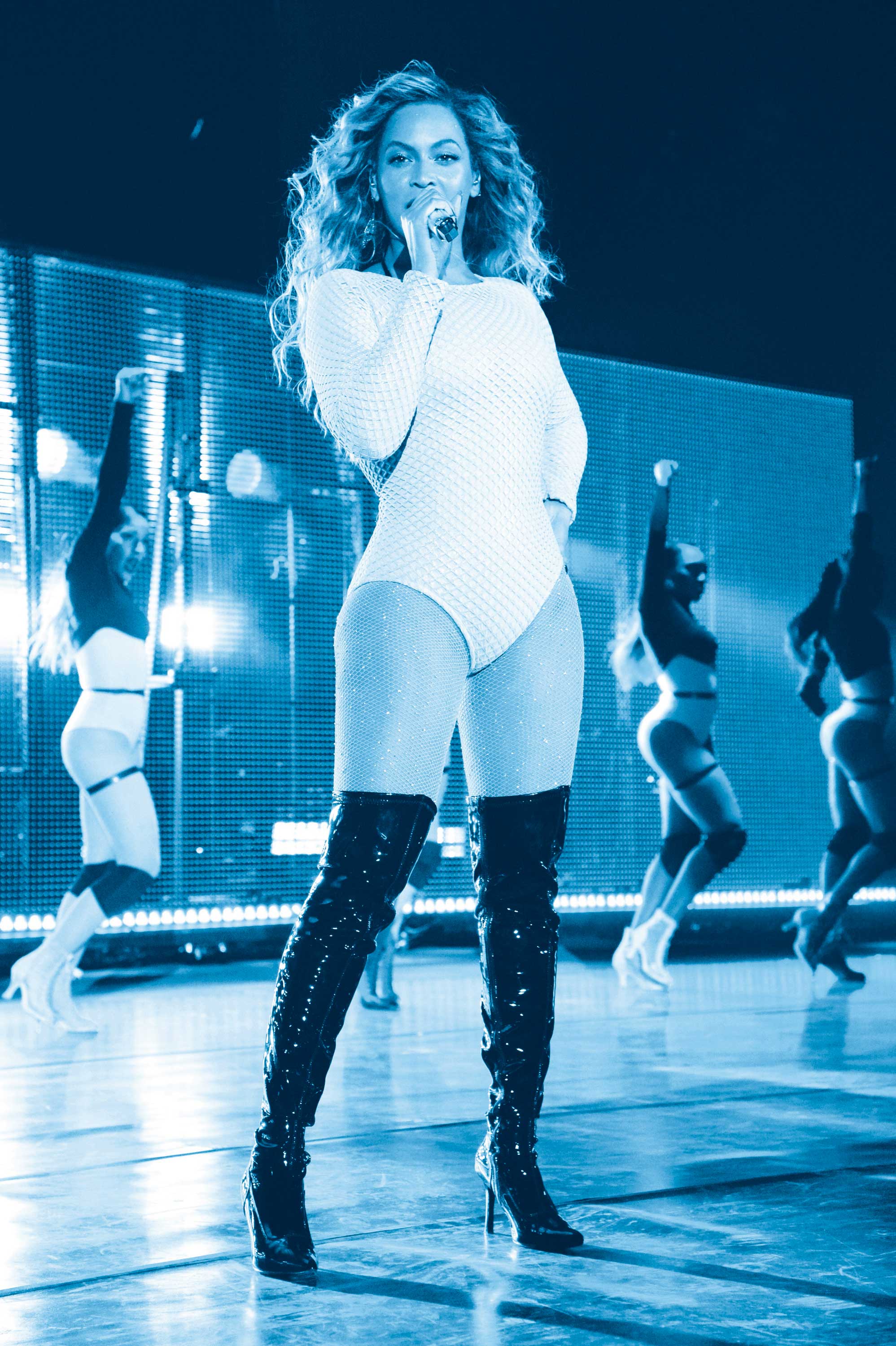

In recent years, a few high-profile artists have tried to break that cycle. Radiohead announced its 2007 album In Rainbows 10 days ahead of its release and let fans pay what they wanted. In 2010, Swedish pop star Robyn put out three minialbums so she could record and tour simultaneously before compiling the best tracks for her album Body Talk. Then Beyoncé unwound everything when she chucked 14 songs with matching music videos onto iTunes with no warning in December 2013.

“Pulling a Beyoncé” quickly became the term for any album rollout with a surprise element. One of the most successful artists to borrow from her playbook is the rapper Drake, who released If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late with little fanfare in February 2015–only to watch it become the first million-selling album released that year.

Not every surprise is about converting Internet buzz into dollars. Last year Miley Cyrus & Her Dead Petz, a set of home recordings, was posted to the singer’s website; she announced it in the final seconds of her hosting duties at the MTV Video Music Awards. Rihanna released Anti in late January, partly to cut her losses amid mounting expectations and bad press following three scrapped singles. Rapper Kendrick Lamar used the tactic to issue material that may not have otherwise been commercially viable: last month’s untitled unmastered. features rough outtakes from his Grammy-winning To Pimp a Butterfly. (It managed to top the Billboard 200 albums chart anyway.)

Some critics predict that fans and artists will–if they haven’t already–tire of the surprise strategy. But the woman who inspired the trend offers clues about its future.

The week before West unveiled The Life of Pablo, Beyoncé surprise-released the politically charged single “Formation,” with a music video referencing Hurricane Katrina and police brutality. She performed the song at the Super Bowl and used the next commercial break to announce a world tour that sold $100 million in tickets in two weeks–all without a new album, which would be less lucrative. (She is, however, rumored to be working on one.) It was a smart move, using the country’s biggest TV event as free advertising. But it was also a glimpse at what the future might hold. Perhaps the next big change to the album isn’t how much notice artists give us or how much they tinker–it’s whether they release one at all.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Nolan Feeney at nolan.feeney@time.com