Not long ago, Dr. Bill Sullivan, an emergency-room physician in rural Spring Valley, Ill., treated a type of patient that has become all too familiar in hospitals across the country. Complaining of abdominal pain, the man asked specifically for Dilaudid, a potentially habit-forming painkiller. Noticing that his record showed a long history of opioid prescriptions, Sullivan suggested a less potent option. The patient’s response, according to the doctor: “Morphine is sh-t.”

Sullivan refused to prescribe the patient’s drug of choice. By doing so, he may have put his hospital at financial risk. That might seem strange, since opioid addiction has become a national epidemic. But the potential economic hit is a direct, if unintended, result of reforms put in place under the Affordable Care Act.

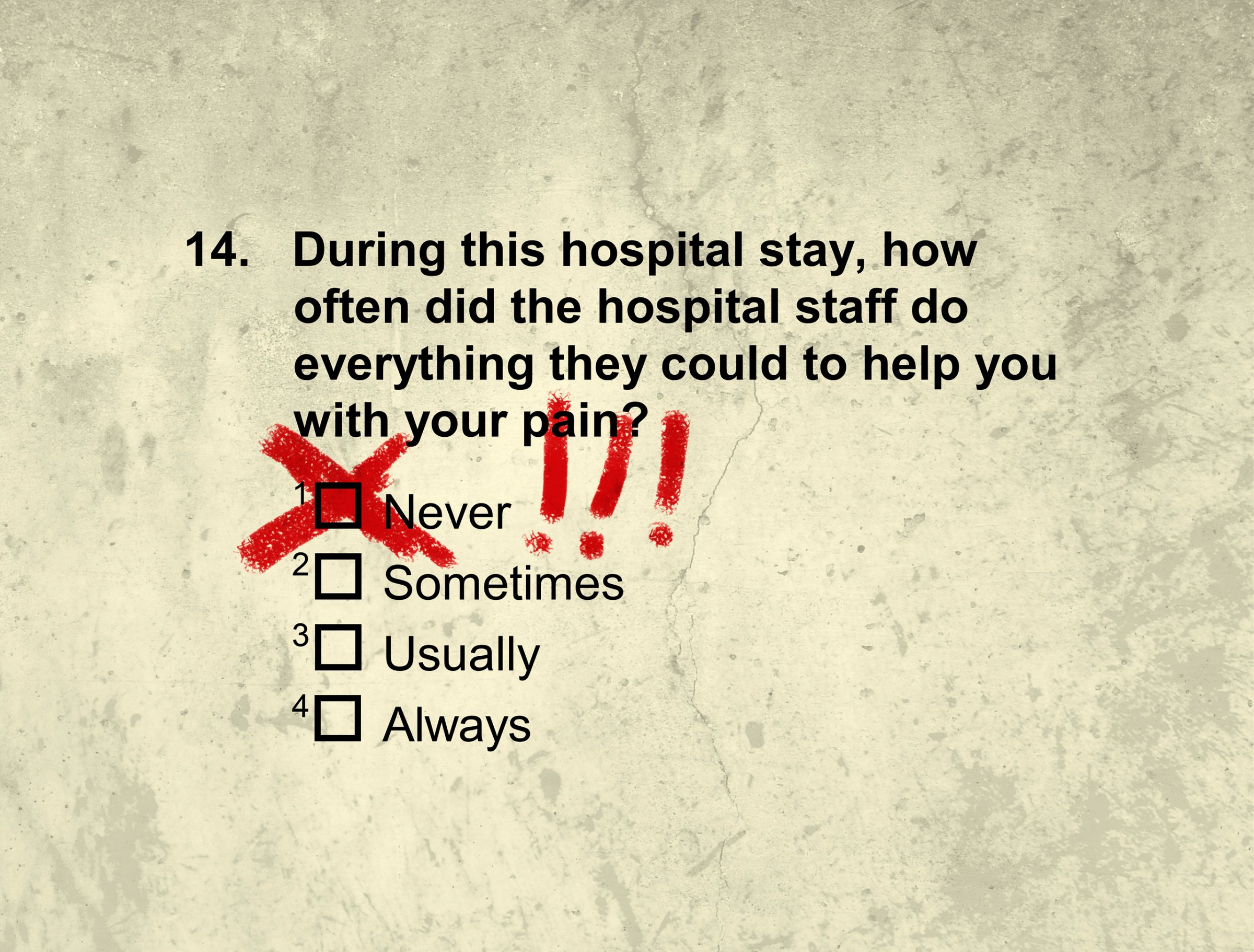

As part of an Obamacare initiative meant to reward quality care, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is allocating some $1.5 billion in Medicare payments to hospitals on the basis of criteria that include patient-satisfaction surveys. Among the questions: “During this hospital stay, how often did the hospital staff do everything they could to help you with your pain?” And: “How often was your pain well controlled?”

To many physicians and lawmakers struggling to contain the nation’s opioid crisis, tying a patient’s feelings about pain management to a hospital’s bottom line is deeply misguided—-if not downright dangerous. “The government is telling us we need to make sure a patient’s pain is under control,” says Dr. Nick Sawyer, a health-policy fellow at the UC Davis department of emergency medicine. “It’s hard to make them happy without a narcotic. This policy is leading to ongoing opioid abuse.”

That abuse has led to a full-blown crisis. Since 1999, fatal prescription-opioid overdoses in the U.S. have quadrupled. According to the CDC, more than 47,000 Americans died of a drug overdose in 2014, a record high, and more than 60% of those deaths involved an opioid. U.S. emergency rooms now treat more than 1,000 people every day for misusing prescription opioids.

Patient-satisfaction surveys are not the cause of this crisis, of course. But there is research to support some doctors’ contention that they’re making the problem worse. A 2012 study in the Archives of Internal Medicine found that the most satisfied patients are more likely to spend more on prescription drugs and have higher mortality rates. In a 2014 survey published in Patient Preference and Adherence, over 48% of doctors reported prescribing inappropriate narcotic pain medication because of patient-satisfaction questions. One doctor wrote that drug seekers “are well aware of the patient satisfaction scores and how they can use these threats and complaints to obtain narcotics.”

CMS, which is part of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), disputes any link between its surveys, a hospital’s reimbursement money and opioid abuse. In March, agency doctors wrote in JAMA that the patient-satisfaction survey accounted for 30% of a hospital’s total performance score in fiscal year 2015, with pain management one of eight equally weighted dimensions, along with factors like cleanliness and quietness and nurse communication. (CMS did not respond to interview requests.)

Still, lawmakers are concerned. Republican Senator Susan Collins, whose home state of Maine saw a 27.3% rise in its drug-overdose death rate from 2013 to 2014, has called for HHS to investigate the connection between the surveys and inappropriate prescriptions. “Health providers are telling me that these questions are written in a way that makes them fear a lower reimbursement if patients did not answer them in the affirmative,” says Collins. “For a small rural hospital in Maine to lose a certain percentage of their Medicare reimbursements is a big deal.” In April, four Senators–two from each party–sponsored a bill that would untie reimbursements from pain-management questions. An earlier measure attracted bipartisan support in the House. Says West Virginia Representative Alex Mooney, who introduced the bill: “It’s a simple fix that can have significant results.”

For more on these ideas, visit time.com/ideas

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Sean Gregory at sean.gregory@time.com