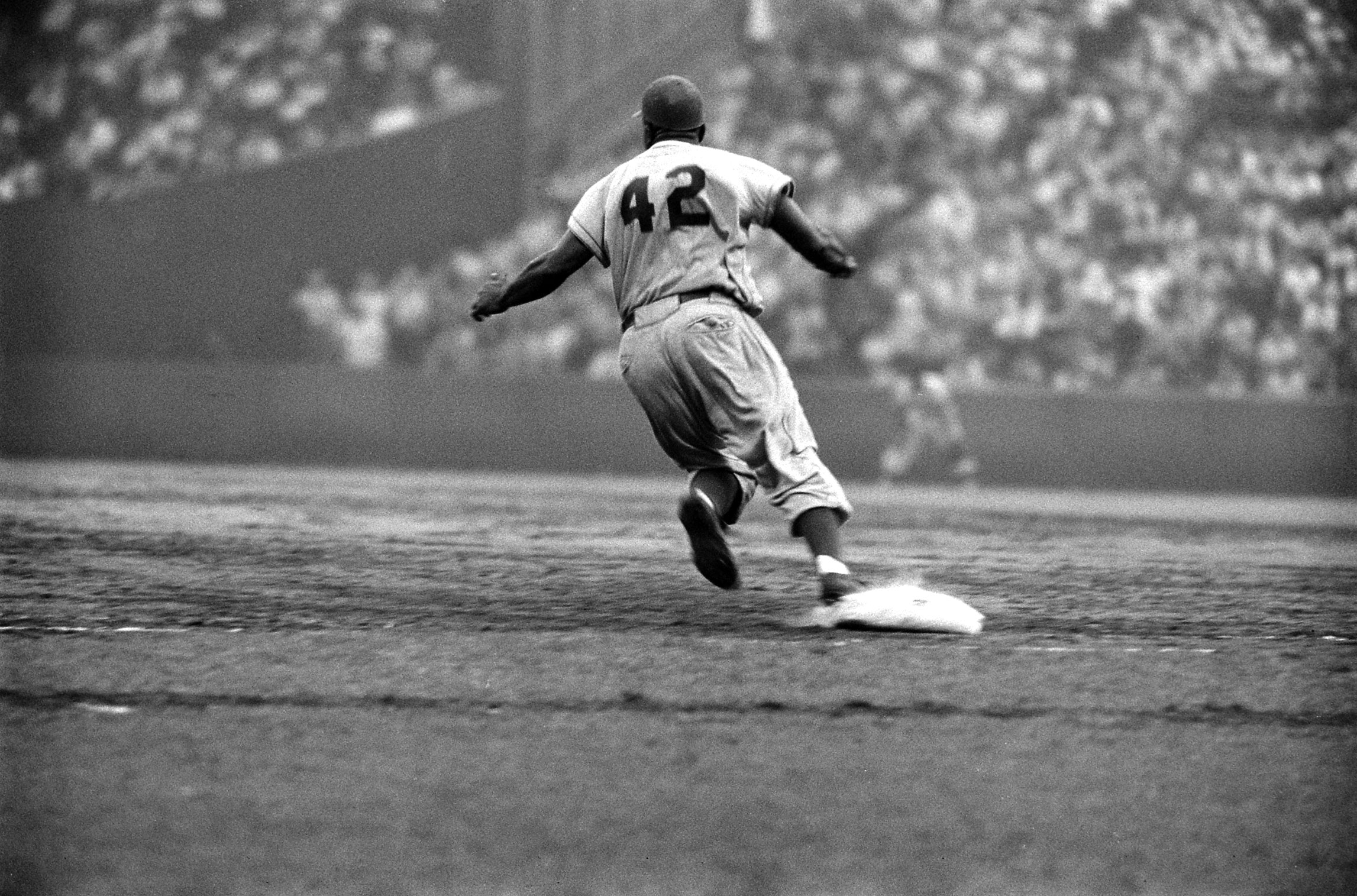

This April 15 will mark the 69th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s barrier-breaking first game in major league baseball. Over that transformational first summer, Robinson dazzled fans with his graceful blend of speed and power, while responding with quiet restraint to the withering barrage of hate he faced on and off the field. His success made him the most famous black man in America and paved the way for other talented black players to join him in the integrated big leagues. It’s a well-told story, but it’s incomplete.

In reality, Robinson was a stubborn, highly intelligent man of deeply held convictions, who, over his 53 years, rarely missed an opportunity to speak out against prejudice and injustice, and who worked tirelessly for equality and opportunity for all. In focusing almost exclusively on the Robinson who “turned the other cheek,” we’ve denied him his voice and shaped a safer and simpler narrative that reveals our greater comfort with an unthreatening, muzzled pioneer who needed the helping hand of well-meaning whites. The full story is far more complicated and compelling, and has more to teach us today—if we’re willing to listen.

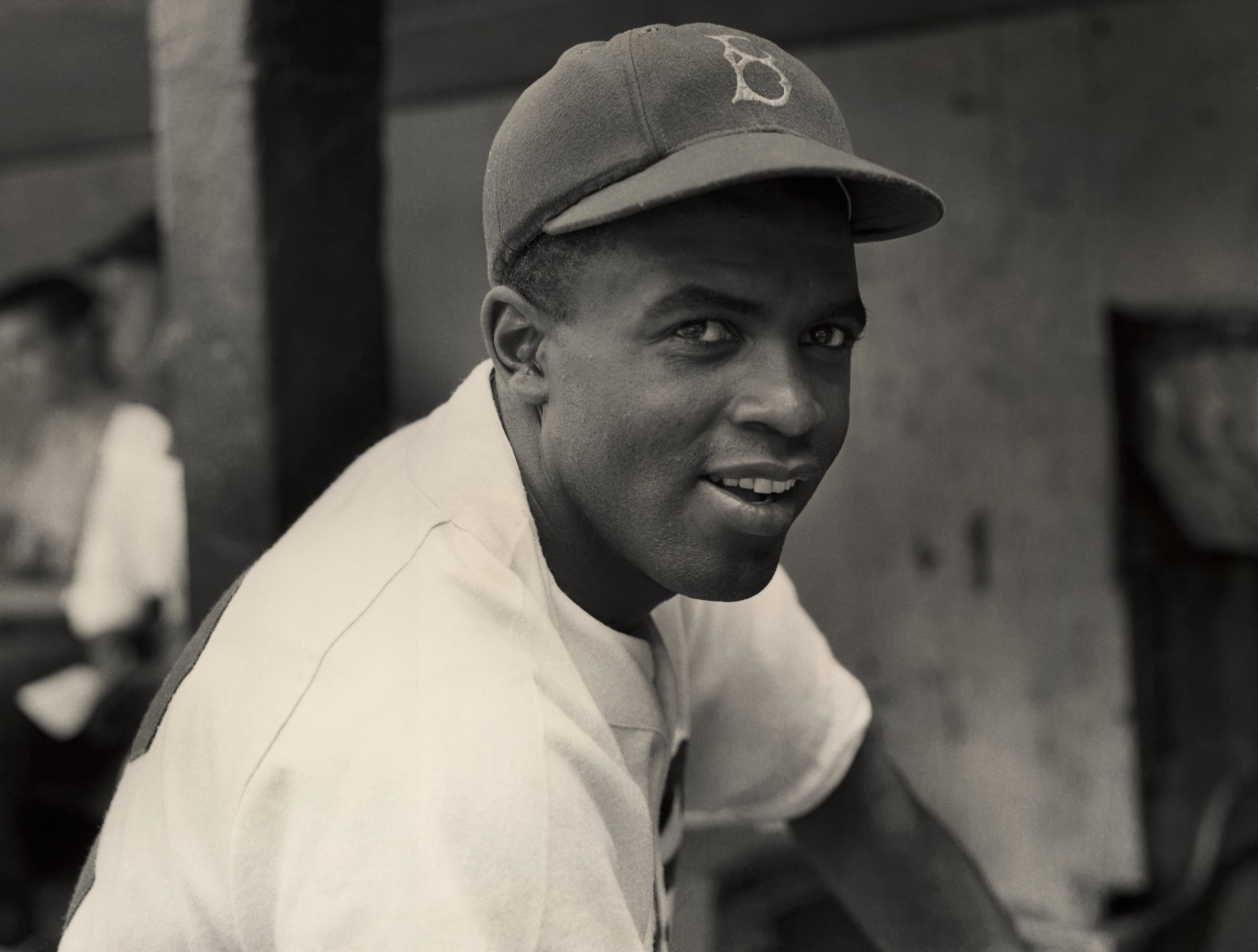

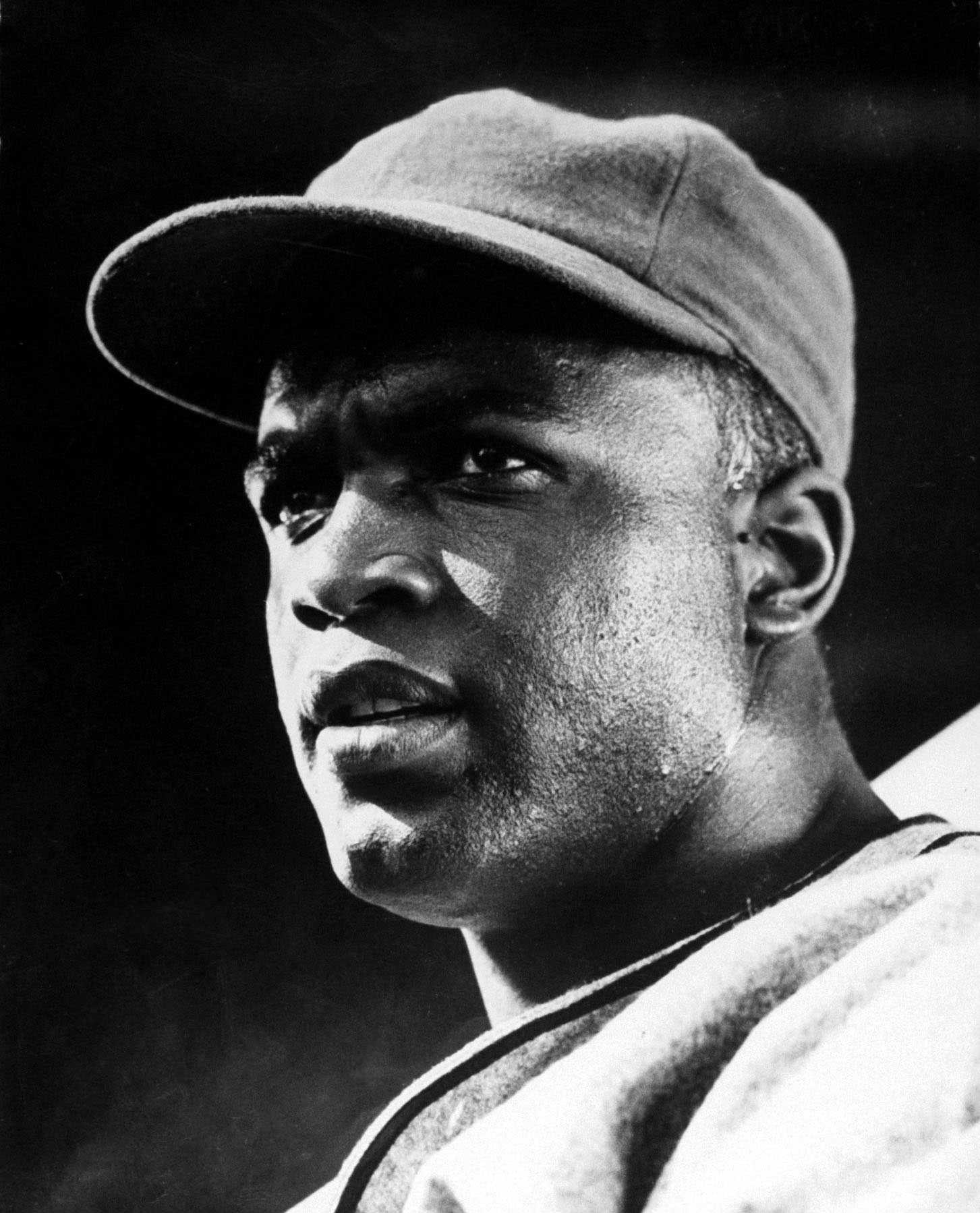

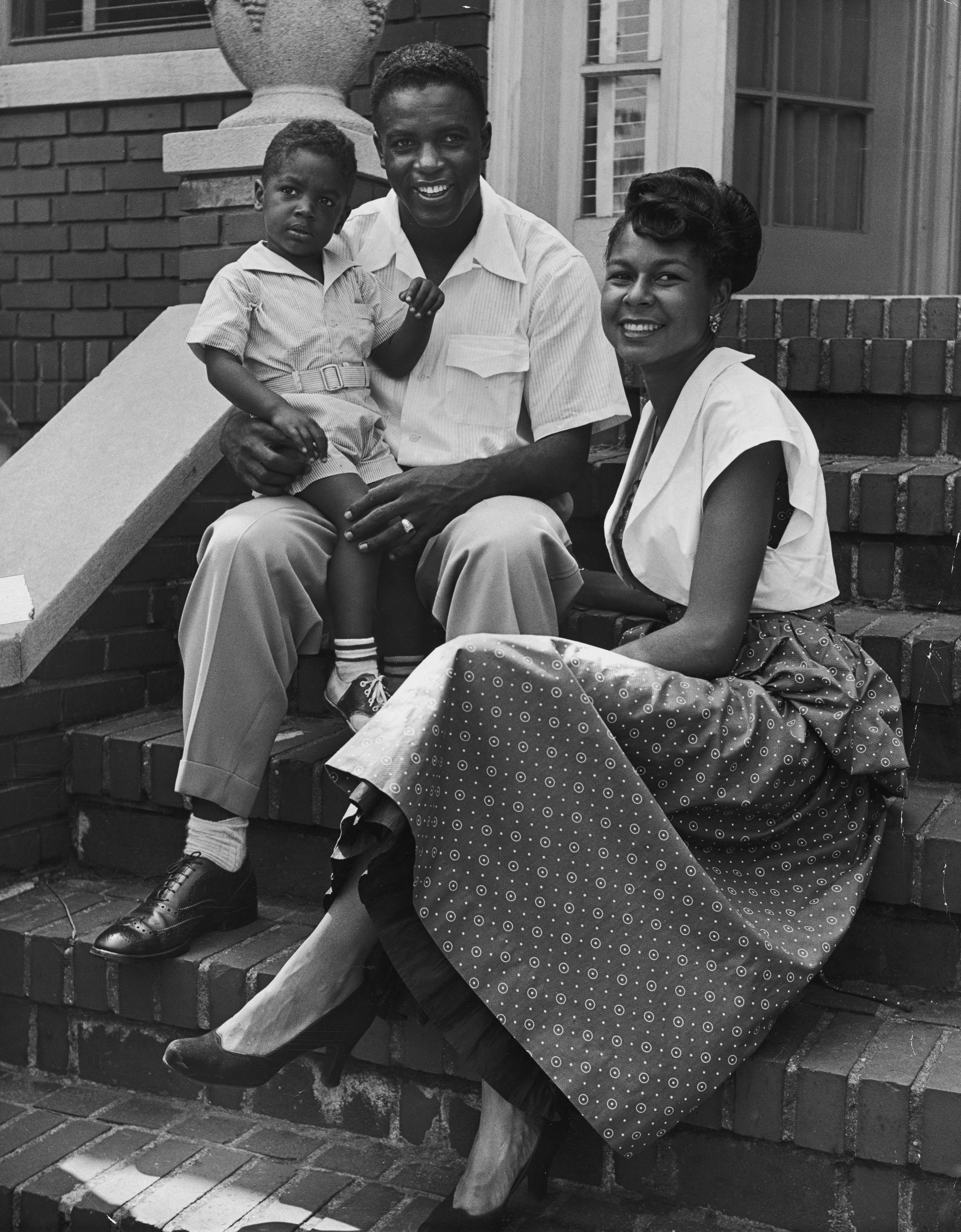

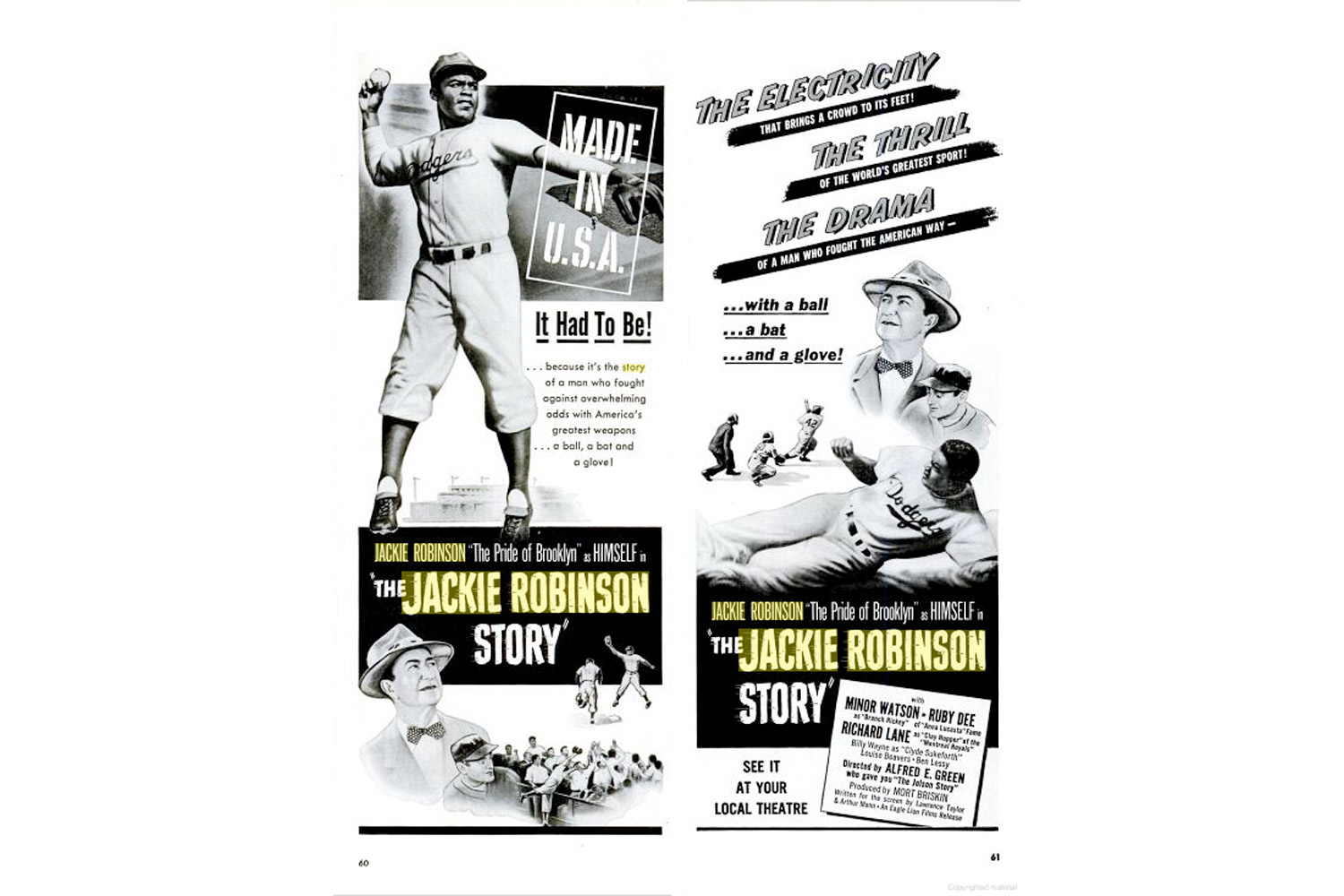

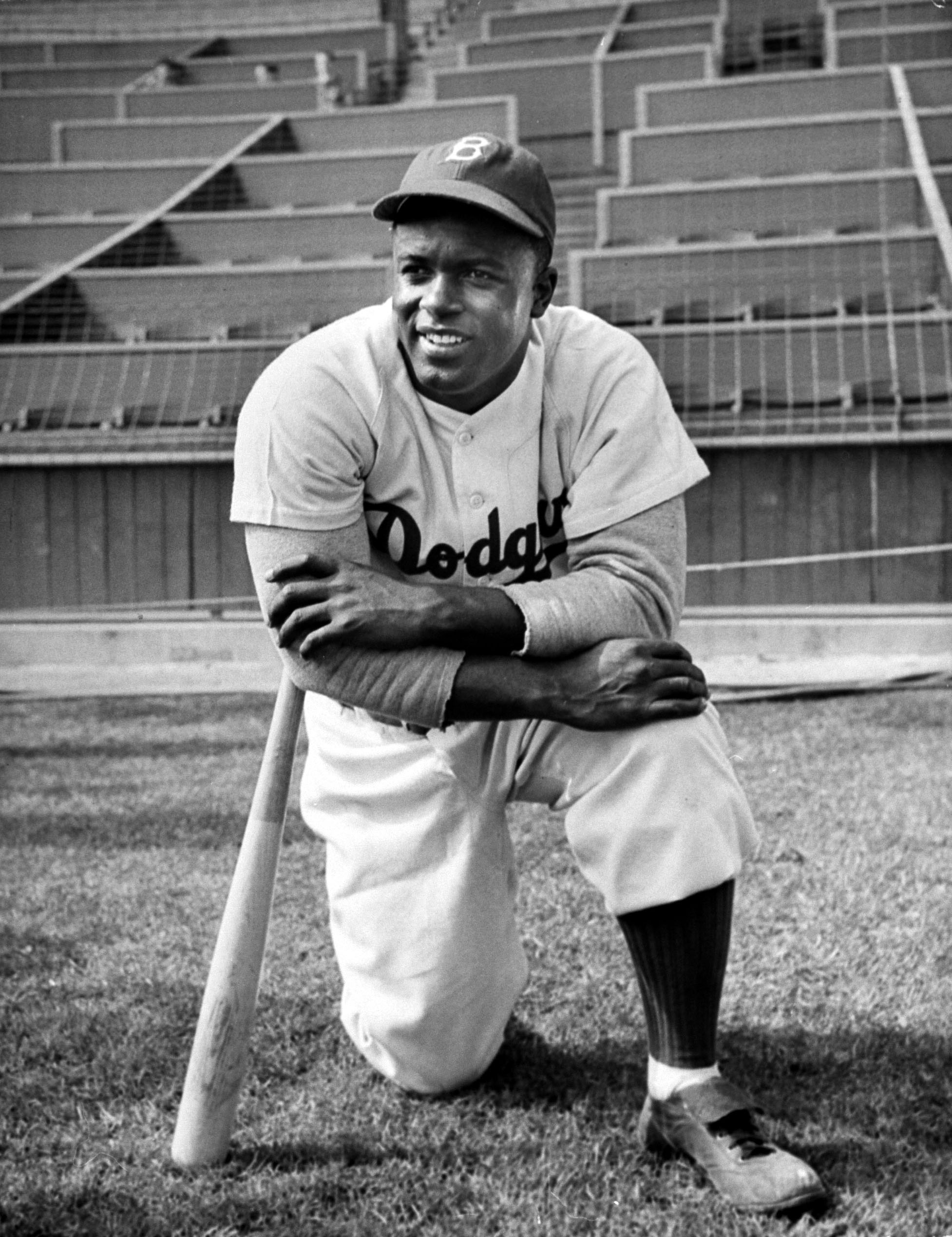

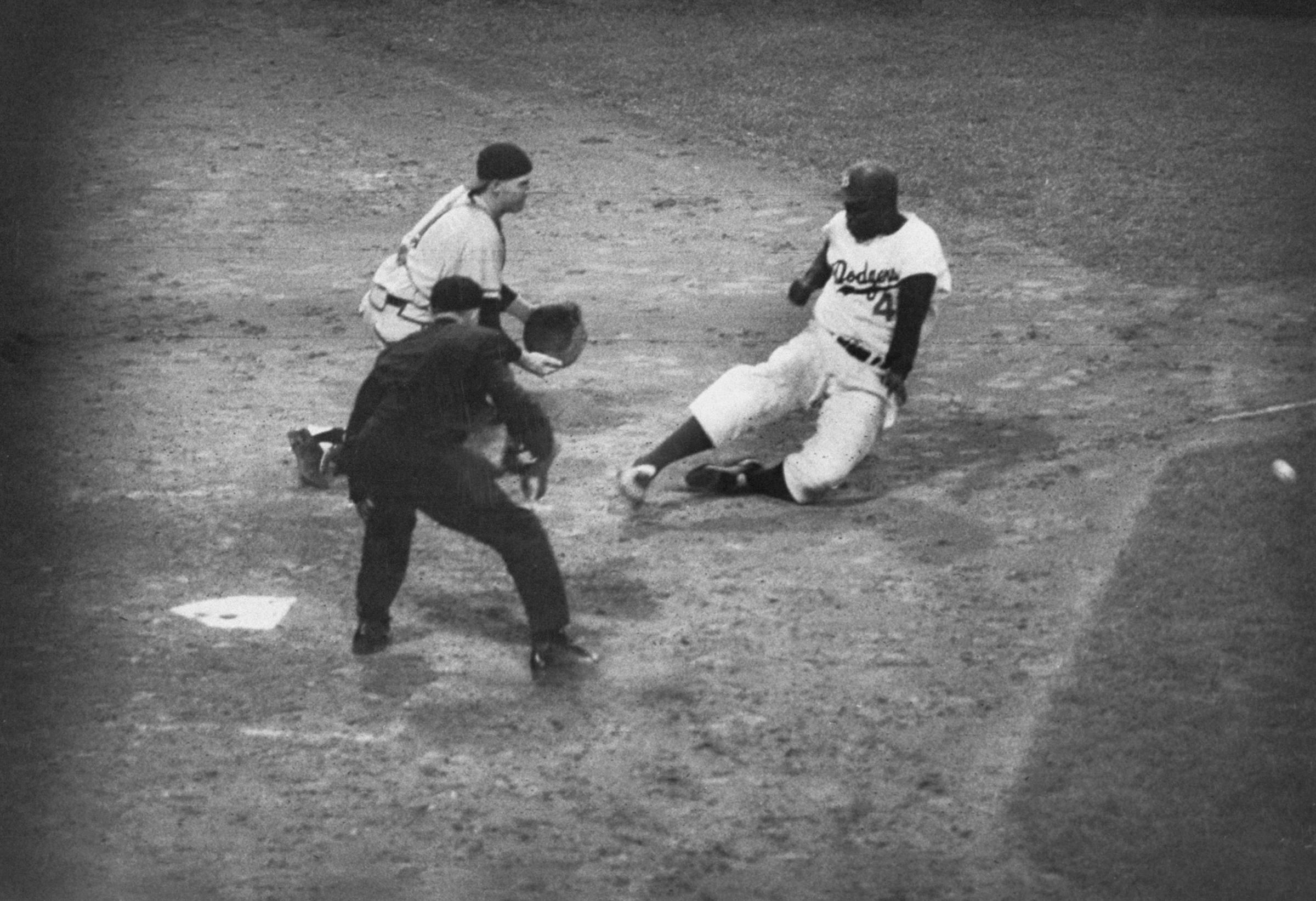

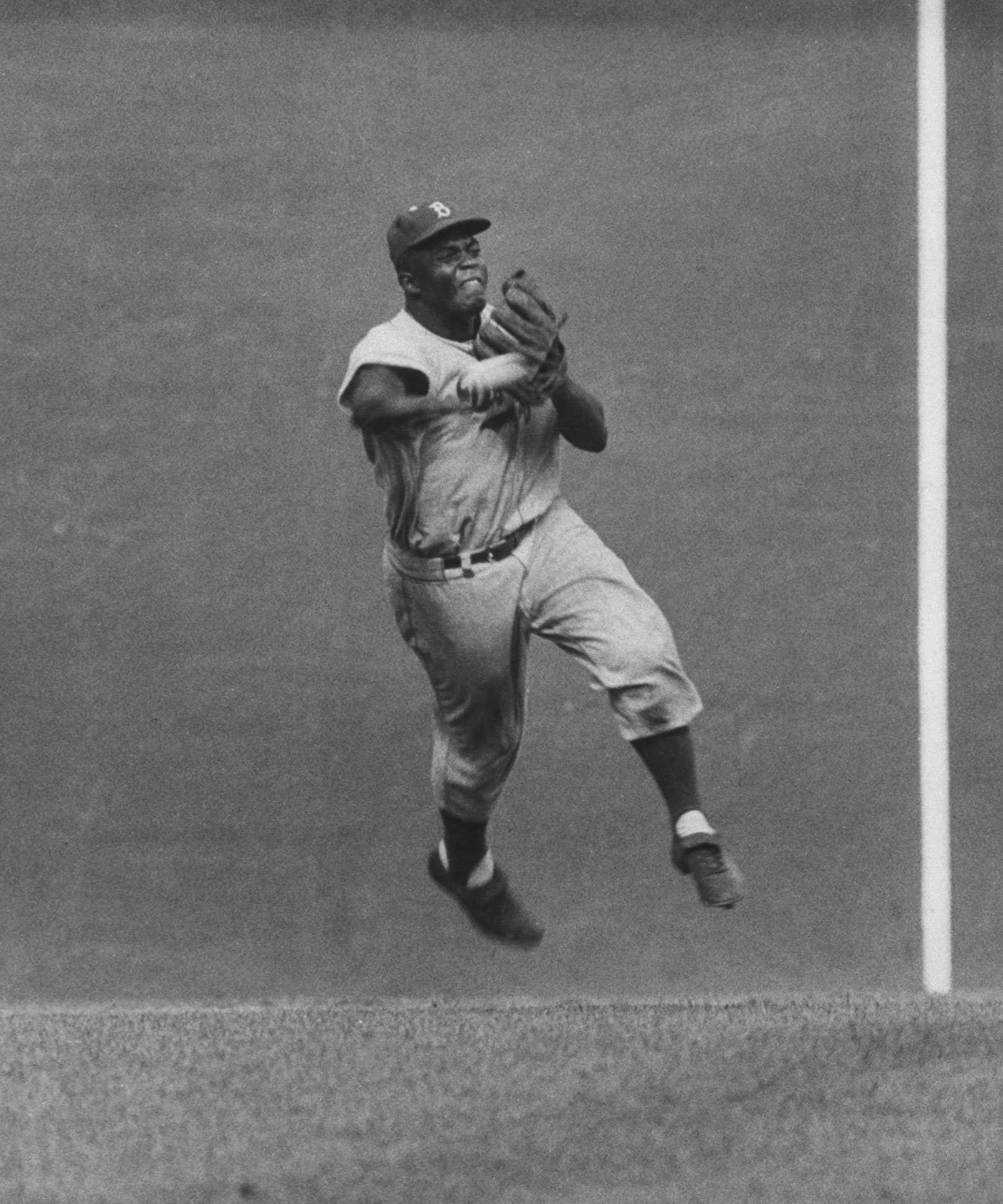

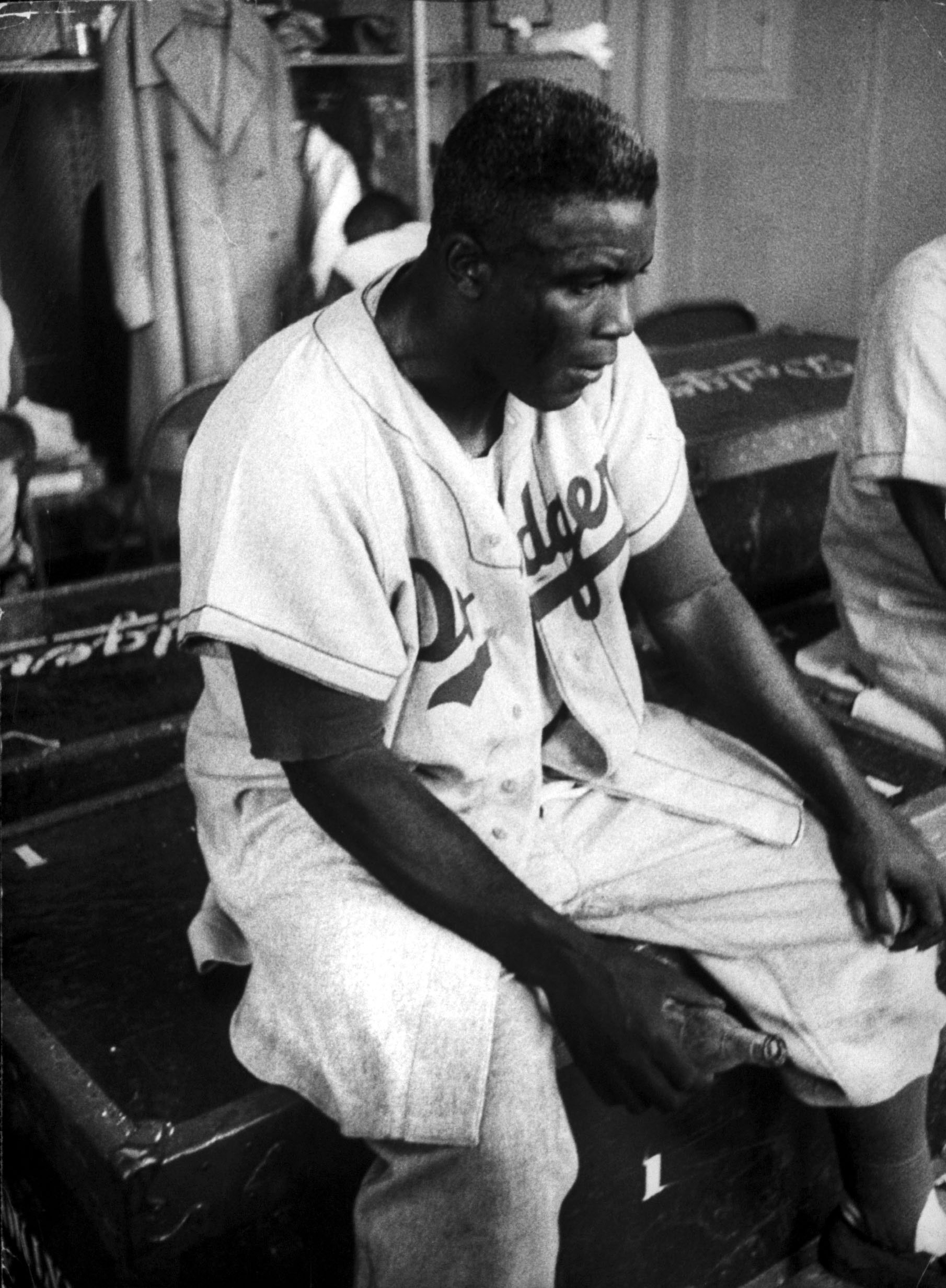

LIFE With Jackie Robinson: Rare and Classic Photos of an American Icon

The silent stoicism that marked Robinson’s early days with the Brooklyn Dodgers was contrary to his character. Growing up in depression-era Pasadena, Calif., Robinson spoke out against the injustice he saw nearly everywhere. He stood up to racist neighbors and Jim Crow customs, refusing to sit in the segregated section at the movie theater or leave a Woolworths lunch counter until he was served. Once, he was arrested for singing a song that a policeman found offensive. Another time, an officer, rushing to the scene of an argument to which Robinson was a bystander, pulled a gun on him before knowing who was to blame. As a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army during the Second World War, Robinson faced a court martial after refusing an order from a white civilian bus driver to move to the back of a military bus at Fort Hood, Texas—this was 10 years before Rosa Parks’s own bold act of defiance on a Montgomery, Ala., bus.

Brooklyn’s general manager, Branch Rickey, a high-minded opportunist, knew of Robinson’s scrapes with the law and his early discharge from the U.S. Army before signing him to the Dodgers. In these incidents, Rickey saw a man of considerable character who, though strong-willed and defiant, would care enough about succeeding that he would, for a time, suppress his natural impulse to fight back—and during his first few seasons, Robinson mostly did. But once the place of blacks in the game was secure, it was no longer necessary for Robinson to keep quiet. And, as President Barack Obama told us, Jackie Robinson “had purchased the right to speak his mind many times over.”

Throughout his remaining playing days, Robinson used his enormous fame to bring attention to the countless ways in which his world was patently unjust. He criticized umpires whom he believed were treating him unfairly, demanded that hotels provide equal access to him and his black teammates, and accused the New York Yankees of prejudice for failing to promote any black players to their team. When, during a mid-game birthday celebration for a popular southern-born player, the grounds crew raised a Confederate flag over Ebbets Field, Robinson fumed. “Who would ever let Jim Crow back in the ballpark?” he asked resentful teammates, who were enjoying the festivities. The press, many of whom had once praised him for turning the other cheek, took exception to his outspokenness, calling him ungrateful and urging him to be a baseball player, not a crusader. Bill Keefe, sports editor of the New Orleans Times-Picayune, declared that “no ten of the most rabid segregationists accomplished as much as Robinson did in widening the breach between the white people and Negroes.”

While Robinson appeared to be on his own—Jimmy Cannon once called him “the loneliest man I have ever seen in sports”—he wasn’t. But too often we’ve given all the credit to “white saviors” for coming to his rescue. Yes, Branch Rickey, aided by social forces that ripened the climate for integration, ably set it all in motion. And yes, Pee Wee Reese was a reliable and respectful double play partner for years. But it was Rachel Robinson, his wife, who consistently provided sage counsel and wrapped a comforting arm around him when the burden of his task became almost unbearable.

After baseball, Robinson wrote hundreds of newspaper columns about inequality and injustice and raised money for the NAACP and SCLC. When Martin Luther King, Jr. asked Robinson to help boost morale among civil rights workers in Georgia or Alabama, Jackie took the next available flight. He also sparred with Malcolm X over the direction of the civil rights movement, and later seemed out of touch in forcefully dismissing the arguments of younger, more militant activists who had grown frustrated with the slow pace of change, including Muhammad Ali. But Robinson continued to make his voice heard.

He stumped for politicians whom he believed would best support the interests of African Americans, including Richard Nixon, a decision he later regretted. At the 1964 Republican National Convention, Robinson served as a special delegate, rallying a tiny band of African Americans who were forsaken when the party lurched sharply to the right. The eventual nominee was Barry Goldwater, who had voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and whose supporters included the John Birch Society and the Ku Klux Klan. At a rally outside the convention, Robinson thundered his disapproval. “I am an American Negro first, before I am a member of any party,” he told the audience. “We will not stand silently for any major party nominating a man who in my opinion is a bigot and a man who will attempt to prevent us from moving forward.” That November, Robinson voted for Lyndon Johnson, who beat Goldwater in a landslide.

It will always be important to honor Jackie Robinson’s courageous restraint, but now, more than ever, we should remember him in full, celebrate his outspokenness, even when misguided, and let his life serve as a reminder that stamping out racism and injustice is a full-time job that requires constant vigilance and unyielding activism.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com