Ever since she was a schoolgirl in the small Punjabi town of Bhatinda, some 320 km west of New Delhi, Shivali Goel has been the kind of person Indian policymakers dream about. Goel was born in the 1990s, as India began to open up to the world by embracing market-friendly reforms. Now 21, she is one of the more than 50% of Indians who are under the age of 25 and part of the two-thirds of the country’s 1.3 billion people under 35. That makes Goel a member of the fabled “demographic dividend” that the country’s leaders believe will power India’s economic ascent as the world’s other major economies age.

By 2020, the average Indian will be 29 years old, according to a recent Indian government report. The average American and Chinese, on the other hand, are forecast to be 37. The figure for Western Europe is comparatively ancient: 45. Over the next 20 years, as the labor force in the industrialized world shrinks by 4%, India’s is expected to swell by nearly a third.

For India’s boosters, the conclusion is clear—the country’s youthful working-age masses, coupled with its vast domestic market for goods and services, will give it an unrivaled competitive edge over other economies. Ten years ago, India’s then Commerce Minister Kamal Nath spoke of how “at a time when much of the developed world is aging,” India’s young people were “raring to go.” Today, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi makes a similar pitch. “We have the three D’s. It is our unique strength. Demographic dividend, democracy and we have the demand,” he said during a visit to Facebook’s headquarters in Menlo Park, Calif., in 2015.

Goel’s story sits well with such optimistic proclamations. After high school, she enrolled at the Delhi branch of the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), the country’s leading engineering college. The first member of her family to make it to one of the country’s top schools, Goel, who is now in her final year, has already been hired by a global consulting firm, one of an array of major Indian and international companies that return every year to IIT campuses across the country to find new recruits. “There’s a whole infrastructure here to help us find jobs, and because this is an IIT, there are many that only want to hire graduates from institutes like this,” says Goel. A group of her fellow final-year students all nod in agreement.

But Goel is the exception in India. Though as many as 12 million Indians enter the workforce every year, only 2.7 million new jobs were created in the five years to 2010. And that came during a period of strong economic growth, with GDP expanding by an average of 8% between 2003 and 2011. The reason: unlike China, which relied on labor-intensive factories to drive up its decades-long boom, India’s economic advance has been fueled by IT and other services that employ far fewer people than manufacturing businesses. And of the country’s total labor cohort of nearly 500 million people, 93% find work in what is called the informal sector, doing low-skilled jobs without contracts and benefits. Of the 10.5 million new jobs created by the manufacturing sector between 1989 and 2010, nearly two-thirds were informal jobs.

For India’s young people, these imbalances translate into a desperate struggle to find secure employment. An illustration occurred last year when the government of Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, invited applications for 368 jobs in the local administration. The government was looking for “peons” or office boys—low-ranking positions in the state machinery that involve running errands for senior officials, from fetching files to serving tea. Qualifications included an elementary-school education and the ability to ride a bicycle. Successful applicants could look forward to a monthly pay package worth less than $250 per month.

The job advertisement set off a frenzy, with the government receiving 2.3 million applications. Among those vying for the low-ranking posts were over 250 people with doctorates. More than 100,000 applicants were college graduates. “We were absolutely shocked to see the response,” Prabhat Mittal, an Uttar Pradesh official, told the Hindu newspaper. That wasn’t the first such story to hit the headlines. In 1999 the BBC reported that nearly 1 million people applied for under 300 vacant posts in the West Bengal state government. More recently, in 2010, the hope of securing a job turned fatal for one young man when the rush to join the queue for a police recruitment drive in Mumbai led to a stampede.

But if there aren’t enough jobs for India’s young people, those young people aren’t right for the jobs that exist. On paper, India’s higher-education sector is among the world’s biggest, with some 37,000 universities and colleges. But quantity doesn’t mean quality. Nearly 47% of graduates are “not employable” in any industry role, according to a 2013 survey by Aspiring Minds, a human-resources firm. Employers say they can’t find recruits with the right skills. “The understanding and the applicability of [the theoretical] knowledge is missing,” says Amitabh Akhauri, who oversees company-wide hiring at Jindal Stainless, the country’s biggest manufacturer of stainless steel. “We see it when we go to the [colleges] to interview people. Like many major employers, we invest a lot in training our young recruits when they come to us. We have to.”

The problems begin before higher education. According to the most recent annual education survey by Indian NGO Pratham, learning outcomes are low even as school enrollment in rural India has climbed to nearly 97% for children ages 6 to 14. Only about 24% of children in year three of school could read at levels normally expected of children in year two; in year five, the figure was under 50%. “There is definitely an opportunity with the demographic dividend,” says Narayanan Ramaswamy, who heads the education practice at the Indian arm of KPMG, the accounting and consulting firm. “But there is also a huge challenge in providing the right skills and supplying the opportunities.”

One consequence of the mismatch between the supply of jobs, the quality of education and the demand from India’s young people has been a nationwide scramble for places at top colleges like IIT, where leading employers hunt for new recruits. To qualify, aspirants must sit for an annual standardized test that last year was taken by about 1.3 million students. Similar standardized tests are used by numerous smaller colleges to recruit students. The competition for places is fierce; the country’s 16 IITs, for example, admit only around 10,000 students every year.

The result is an entire industry devoted to prepping students for standardized tests like the one used by the IITs, with private-tutoring centers mushrooming across Indian towns and cities. Roughly 1 out of 4 students turn to some form of private tutoring. A 2013 report from the Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India put the value of the nationwide coaching industry at just under $24 billion. In the country’s cities, the report estimated that as many as 87% of primary-school students and up to 95% of high school students made use of private tutoring. “It’s a big investment,” says Goel, the soon-to-be IIT graduate. “But we have to do it if we want to succeed.” Today, even as Goel moves into the world of work, her younger brother is cramming for the IIT entrance exam at a tutoring center in Delhi.

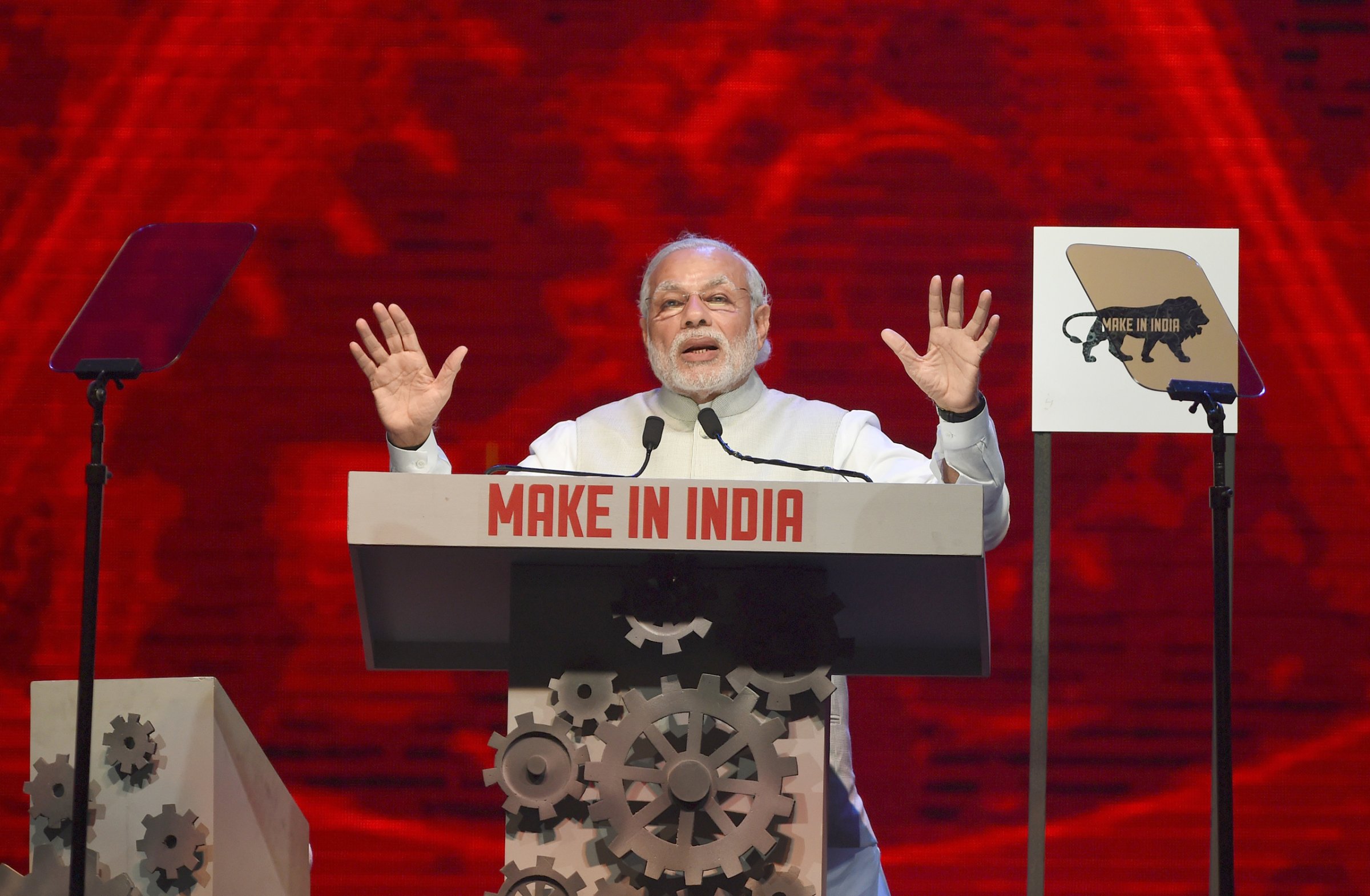

To boost jobs beyond those for the elite, however, India needs to tackle structural obstacles like the many legal hurdles to employment, including restrictive labor laws that force companies with more than 100 employees to seek government approval for layoffs. Companies find it hard to buy land for investment and expansion, and have to navigate a maze of local taxes and tariffs to trade across state lines. It was hope for these and other reforms that powered the optimism felt by Indian industry when Prime Minister Modi came to power in 2014. In the nearly two years since, his government has launched a high-profile initiative, Make In India, to boost manufacturing, with promises to make it easier to operate in the country. “We are committed to make India an easy place to do business,” Modi said at the launch of a weeklong series of events in February to promote his manufacturing drive.

But amid stubborn opposition in Parliament, the Indian leader has struggled to implement his biggest initiatives, including introducing a national goods-and-service tax to replace the local levies and making the acquisition of land for development easier. Critics also argue Modi’s recent budget lacked fresh ideas. The focus was on the welfare of farmers, as Modi prepares for a series of state-level elections in the coming year when rural votes will be crucial. Rajiv Kumar, a senior fellow at the New Delhi–based Center for Policy Research and former secretary general of the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, says he is encouraged by plans by New Delhi to expand education for skilled jobs and to push states to make changes that can generate employment—like land and labor reforms. But at the national level, says Kumar, the Modi government isn’t doing enough to prioritize jobs: “That is the one and only objective. Everything else will follow from that.”

The hope for a secure, well-paying job is what motivates Vipul Sharma, an 18-year-old high school graduate currently enrolled at a private-tutoring center in Kalu Sarai, a south Delhi neighborhood near the IIT campus, which has grown into a mini-tutoring hub. After completing his schooling in Uttar Pradesh’s capital, Lucknow, Sharma moved to Delhi to spend a year studying for the IIT exam. To fund his tutoring, his father, a post-office worker in Lucknow, took out a bank loan. “It’s costly because, in addition to the fees, I have to pay for rent and food,” he says, picking up a coffee in between classes on a bright January afternoon. “I want a good career in a place like Delhi or Mumbai. This is the best way to do it.” What if he doesn’t make it? “I’m not thinking about that. That’s not an option.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com