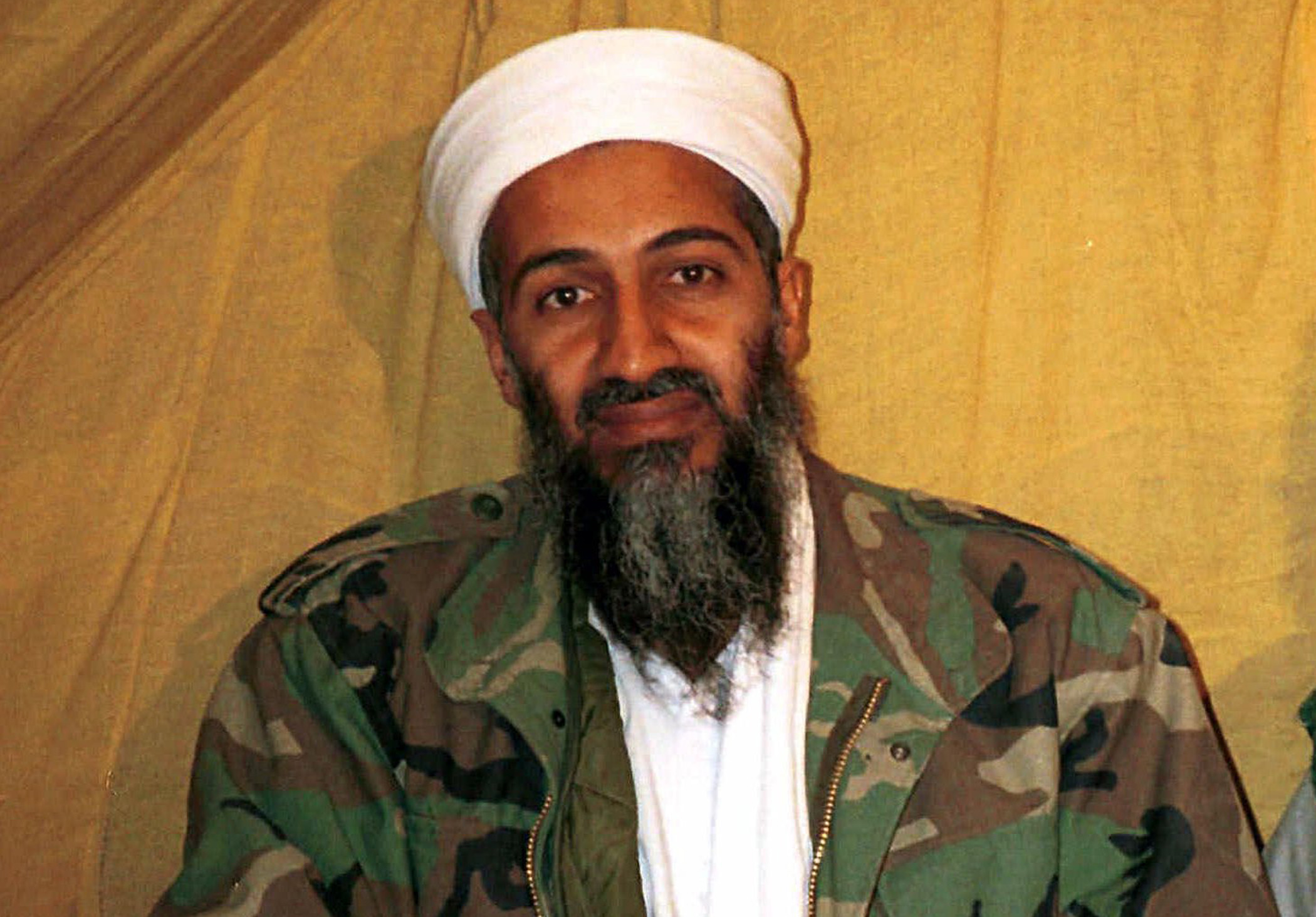

It’s been a tough few days for jihad’s old guard. On March 1, Osama bin Laden’s last will and testament were published, in a trove of documents that had the aging terrorist lamenting the brutality of those who had come after him. And March 5 brought the death of Hassan al-Turabi, the man who first gave al-Qaeda a place in the world by inviting bin Laden to bring his fledgling terror organization to Sudan, the East African country Turabi’s party had taken over.

This was the early 1990s, the salad days of a particular type of political Islam, as militancy was giving way into terror. Shi’ite clerics had taken over Iran in 1979, and the National Islamic Front took power in Khartoum 10 years later. Turabi, with his Ph.D. from the Sorbonne and cheerful, nattering oratory, set out to make to make the African nation the incubator for a new Islamic order. Each year, he brought to Khartoum groups ranging from the militant Palestinian party Hamas to Egyptian Islamic Jihad for annual confabs. Those summits had the full attention of the few counter-terrorism experts then focused on the issue that would reshape the post-Cold War world—but few others even knew they were going on.

It’s a world either man might claim to have made: Turabi by having embraced the Saudi exile, and bin Laden, of course, for mounting the 9/11 attacks that cascaded into events that have kept the entire Arab world in turmoil, and the West perpetually on edge. But they turned out to be yesterday’s men, overtaken even before their deaths by events more brutal than either of them claimed to be comfortable with.

Turabi was the first to separate himself from violent extremism, first of all by separating himself from bin Laden. “All Osama could say was jihad, jihad, jihad,” Turabi later complained about his onetime guest, who on May 18, 1996 the Khartoum government abruptly kicked out of Sudan, at the insistence of the U.S. government. The Saudi extremist boarded a charter flight to Afghanistan, from which he plotted the embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania, the attack on the USS Cole, and, of course, the catastrophe of 9/11. Left behind in Sudan were bin Laden’s houses, businesses, racehorses—and almost all of his cash.

Read More: How Bashar Assad Is Trying to Win the Peace in Syria

It was never nearly as much as widely believed. After 9/11, when it seemed al-Qaeda could do anything, estimates of its founder’s personal fortune routinely ran to $300 million. But the Saudi government had locked up most of his inheritance shortly after he began advocating their overthrow, for allowing U.S. troops to remain in the Kingdom after the First Gulf War. When I talked in November 2001 with businessmen in Sudan, where bin Laden had spent five years, they figured from how excited his business guys would get over a deal that might clear a couple of hundred grand that his actual worth was more like $30 million. And, sure enough, in the last will and testament made public by the U.S. government, bin Laden himself puts the figure at “about $29 million.”*

Almost all the money, he noted, remained in Khartoum. The Sudanese government had refused to hand it over, or to fork over millions it owed him for building a major highway. Bin Laden’s will named the executor who had been charged with getting the money back from the Sudanese (who in the past he had likened to thieves). The chore earned the executor a one-percent finder’s fee. Except for a few meager bequests to kin—two pounds of gold for each male, one for each female, worth about $40,000 and $20,000 respectively at today’s prices—bin Laden directed that most of might be recovered from Sudan be spent “on Jihad.”

But not just any jihad. The emir of al-Qaeda had very specific, even delicate views, on holy war.

“11. Avoid publishing pictures of prisoners after they were beheaded,” bin Laden writes in a letter to a subordinate in Pakistan’s tribal region. Also: “Do not publish pictures of the martyrs who were badly injured, which may terrify the younger generation and the Muslim youth who want to join jihad.”

The letter is undated, but it’s fair to say it’s from a different time, before ISIS.

“12. Avoid displaying some prisoners wearing inappropriate clothes.”

“You know too well that Islam forbids Muslims from killing one another,” he wrote in another letter. “God has repeatedly warned those who kill without a just cause.”

High in his redoubt in Abbotabad, Pakistan, unwilling to trust the Internet—the porn that months ago was reported found in the house was on discs or flash drives—the world’s most famous terrorist became, of necessity, a man of letters. In visits to Sudan after he left, it was possible to get a sense of bin Laden’s life when he lived freely in Khartoum. Those who knew him, including Turabi’s sons, said he swam laps across the Nile, played soccer with neighborhood kids, and, on Friday, went to see his horses race at the track (plugging his fingers in his ears when the fanfare played, believing as he did that the Koran forbade the enjoyment of music).

The 113 documents posted on Bin Laden’s Bookshelf, as the Director of National Intelligence dubbed the repository, also offer something like intimacy. “I also ask you to send me Fatima’s luggage, whatever my daughter was wearing, even her wristwatch, where I can smell her aroma,” reads one passage from the latest digital tranche, referring to a dead relative either of bin Laden or the person writing to him.

Read More: Syria’s Lost Cause

Turabi, who lived to 84, never quite renounced his earlier militancy, but as a politician first he was tethered to a different world. He spent time in prison, as the ruling coalition in Khartoum splintered, and made news for supporting the International Criminal Court’s 2008 indictment of his old ally, President Omar Bashir, for war crimes in Darfur. Turabi himself championed the imposition of Shari’a law that aggravated the horrific civil war with what is now the nation of South Sudan, but his sons insisted their father sought a governing Islam that was both political and ecumenical, urging activists to avoid the sectarianism into which much of the Mideast has devolved.

Bin Laden may never have mellowed. But the extremism he articulated so carefully at his keyboard comes off as less extreme in the brutal world that he made possible. A micro-manger with time on his hands, he dispensed bonuses and offered pointed advice to “brothers” in Pakistan’s tribal regions to stay indoors “except on a cloudy overcast day” in order to avoid U.S. Predator drones. His precise instructions for the delivery of a ransom payment involve “exchanging vehicles in the tunnel between Kohat and Peshawar,” and getting rid of the suitcase the money came in “due the possibility of it having a tracking chip in it.” (The courier who faces the risk of the exchange, he adds, “should not be from the leadership.”)

“In reference to al-Jufi,” he wrote one day in 2008, referring to an individual who apparently has run afoul of the rules, Bin Laden counsels mercy, “a reconciliation council” as opposed to the more ominous option: “an investigation. We do not want to appoint the devil in charge of him in these circumstances.”

As ISIS would make clear enough in a couple of years, everything is relative, even terror. Or, as Osama bin Laden himself put it, “Some harm is less than other harm.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com