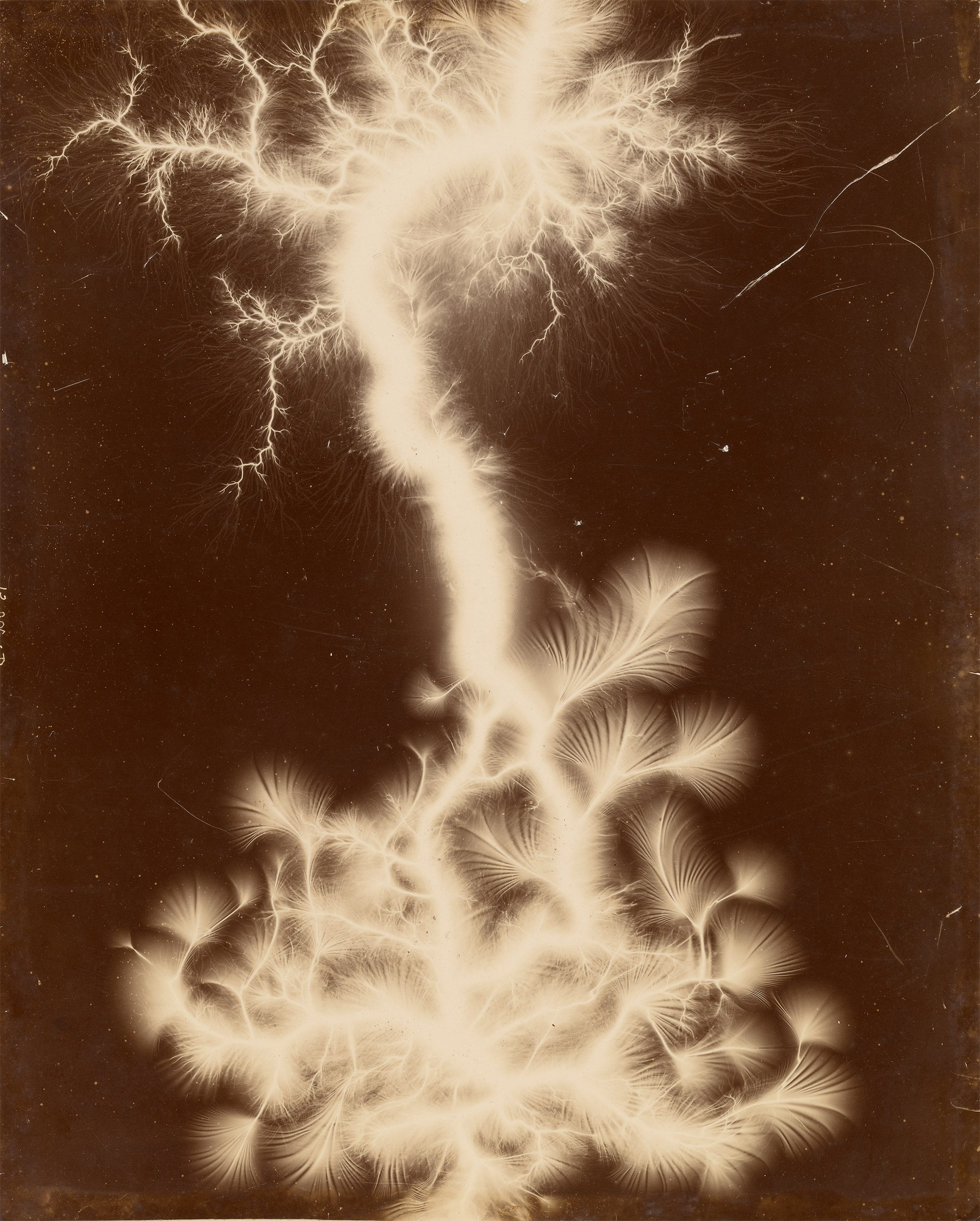

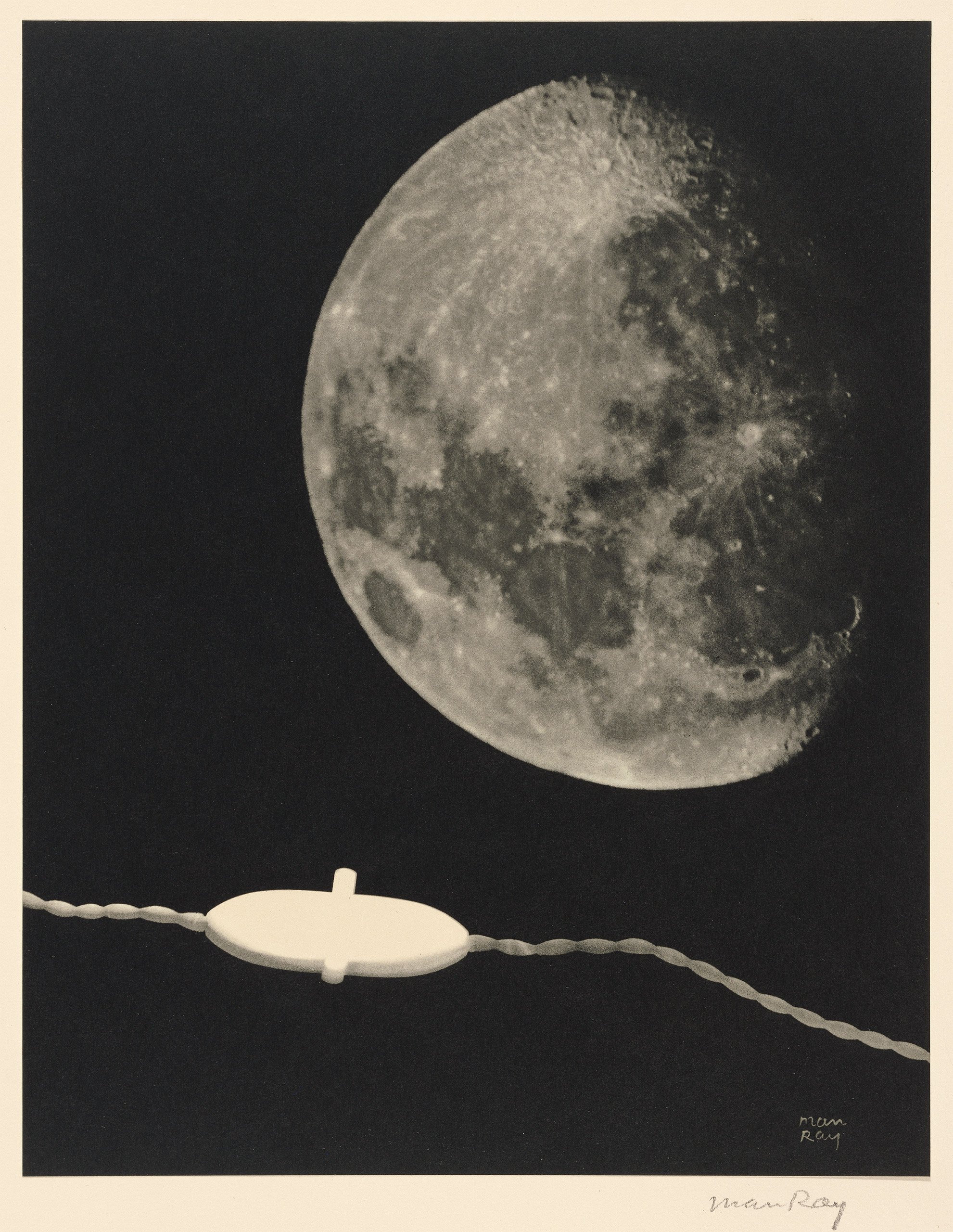

Has a photograph ever shocked you? Maybe not like a painful jolt of electricity but by expanding an understanding or shaking a long held one. The powers of electricity altered the course of civilization in dazzling ways and had an especially profound impact on photography. This early and intertwined relationship is the subject of In Focus: Electric!, an exhibit of photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum‘s permanent collection, that includes Robert Adams, Andre Kertesz, Andreas Feininger and Danwen Xing.

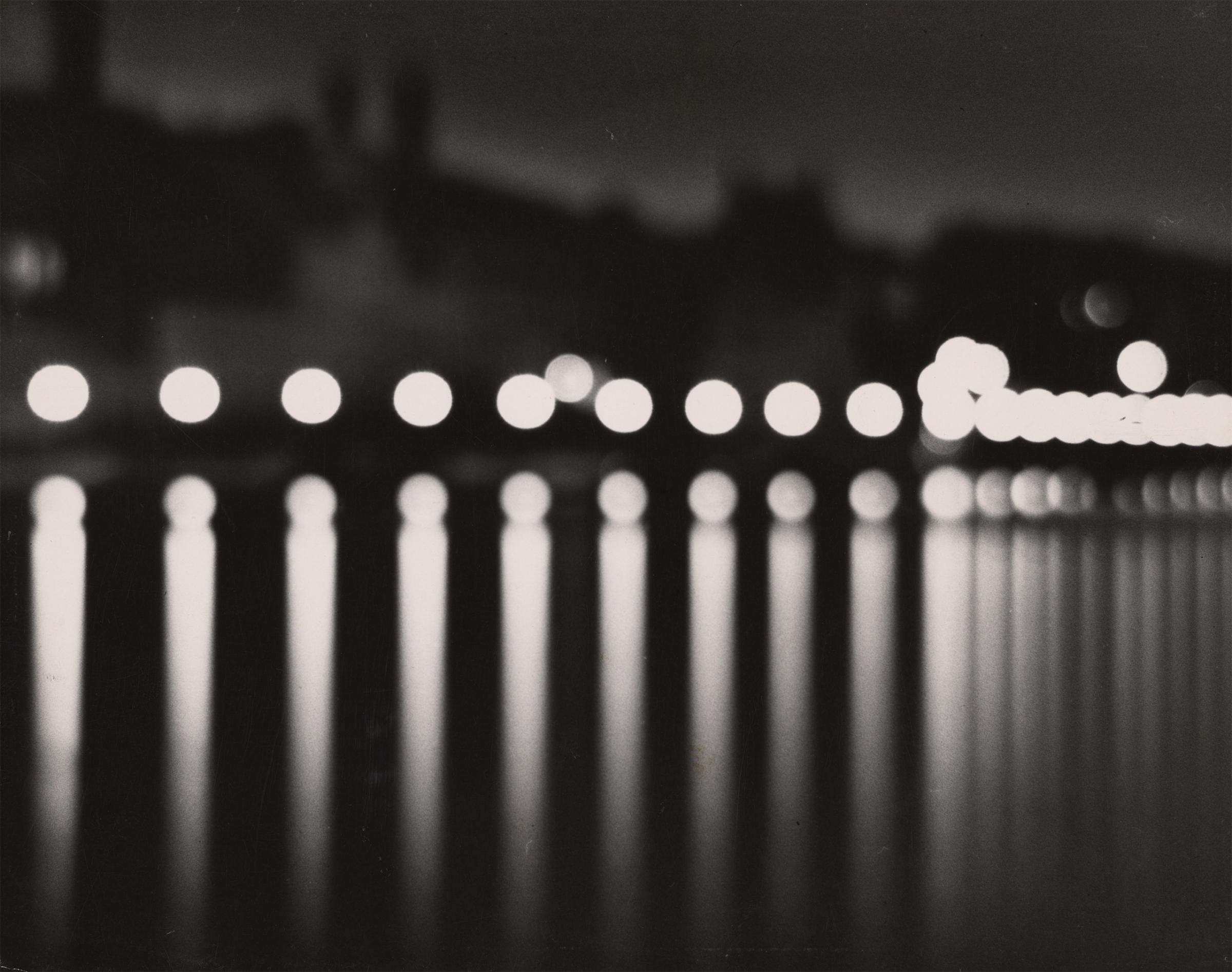

Worldwide access to electricity, according to The World Bank, has increased from 76% in 1990 to 85% in 2012, powering millions of digital cameras, flashes, computer editing software and storage devices. But electricity and photography weren’t always so pervasive. Photography first began as a mechanical and chemical process, reliant on natural light. As electricity crept into daily life, photographers capitalized on the glowing current as a source of light to illuminate new landscapes. Alfred Stieglitz chose New York City lamp posts on a misty night in 1897 to make his exposure. His street-scene photograph would have been impossible without the development of this new technology.

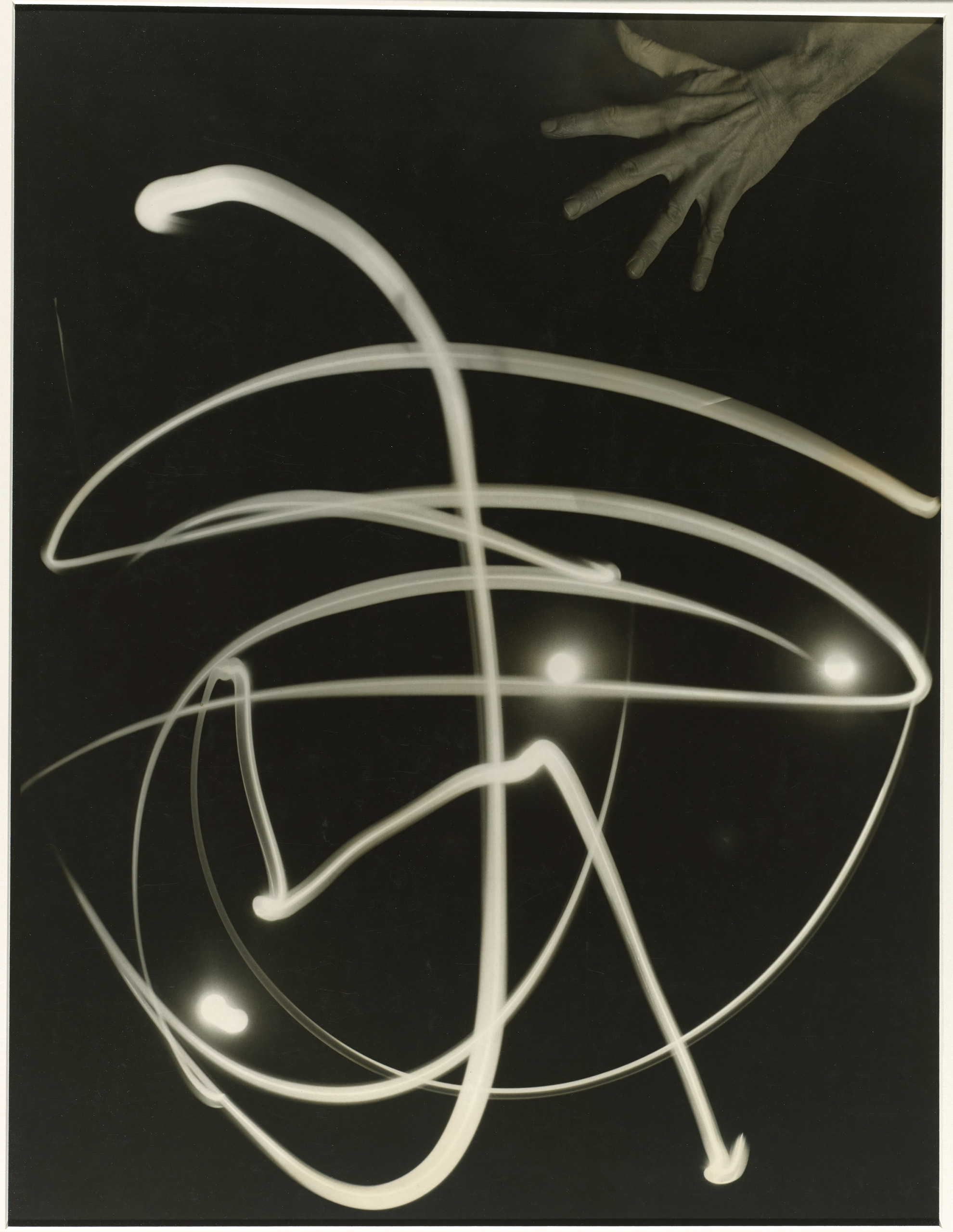

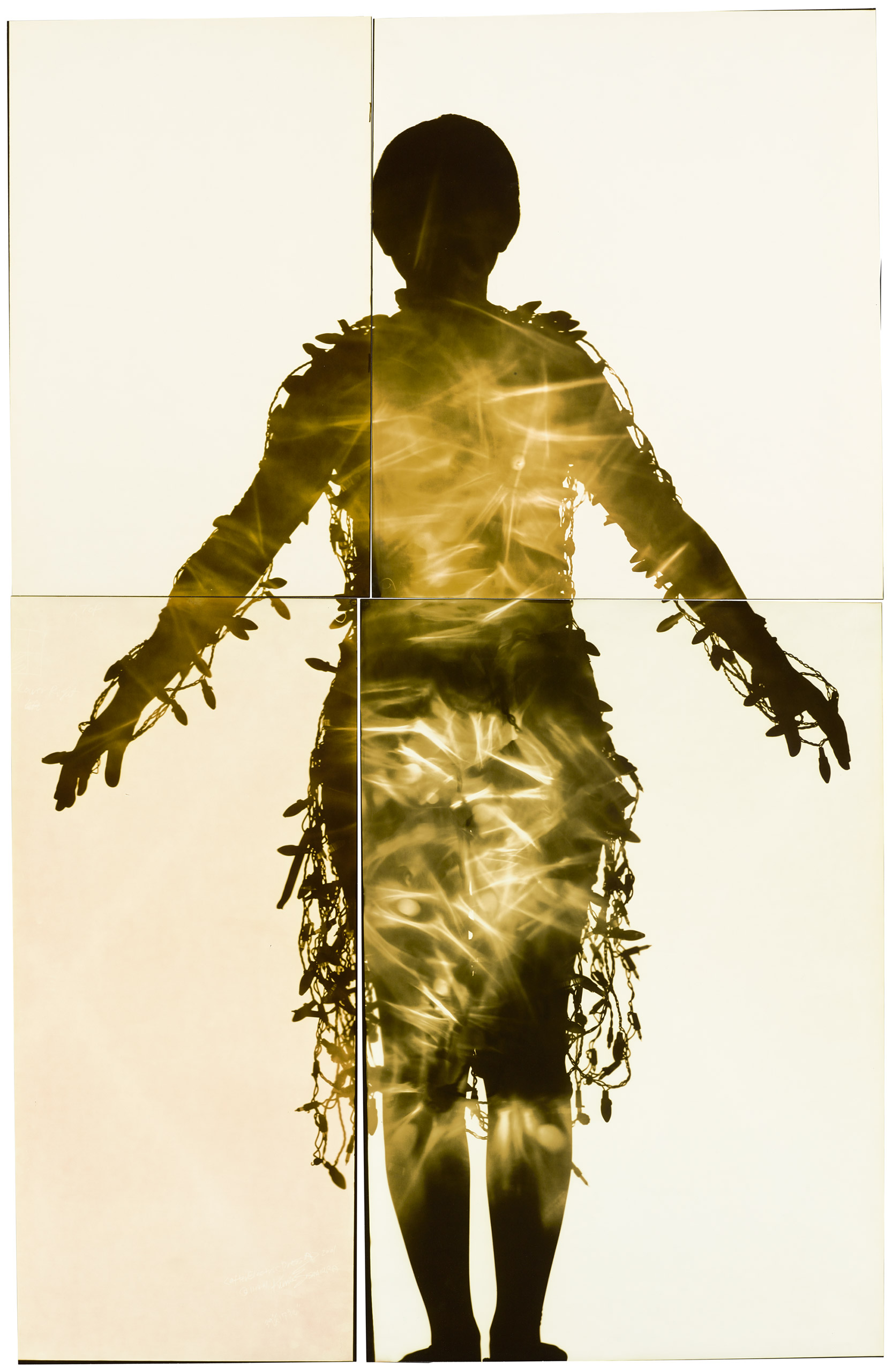

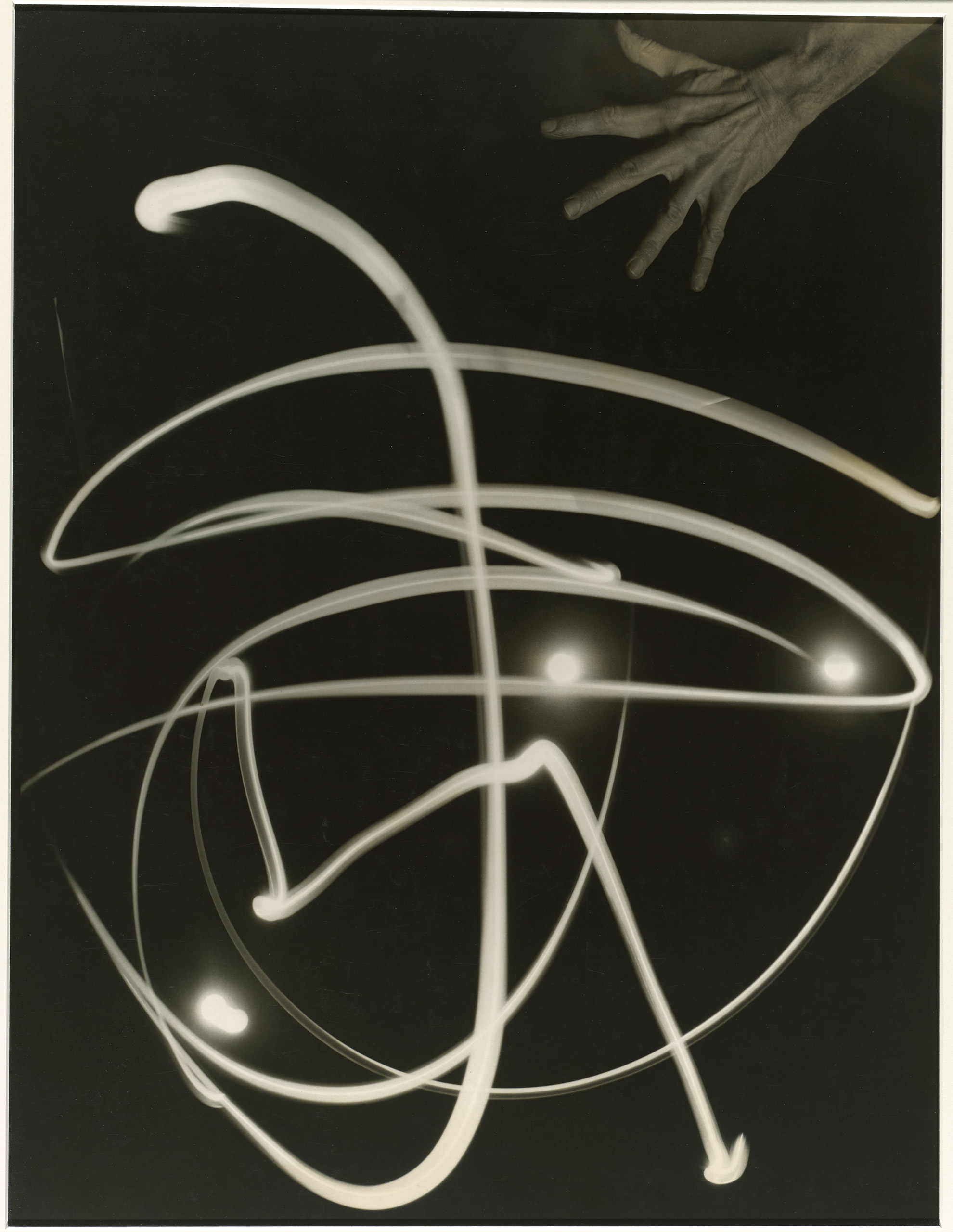

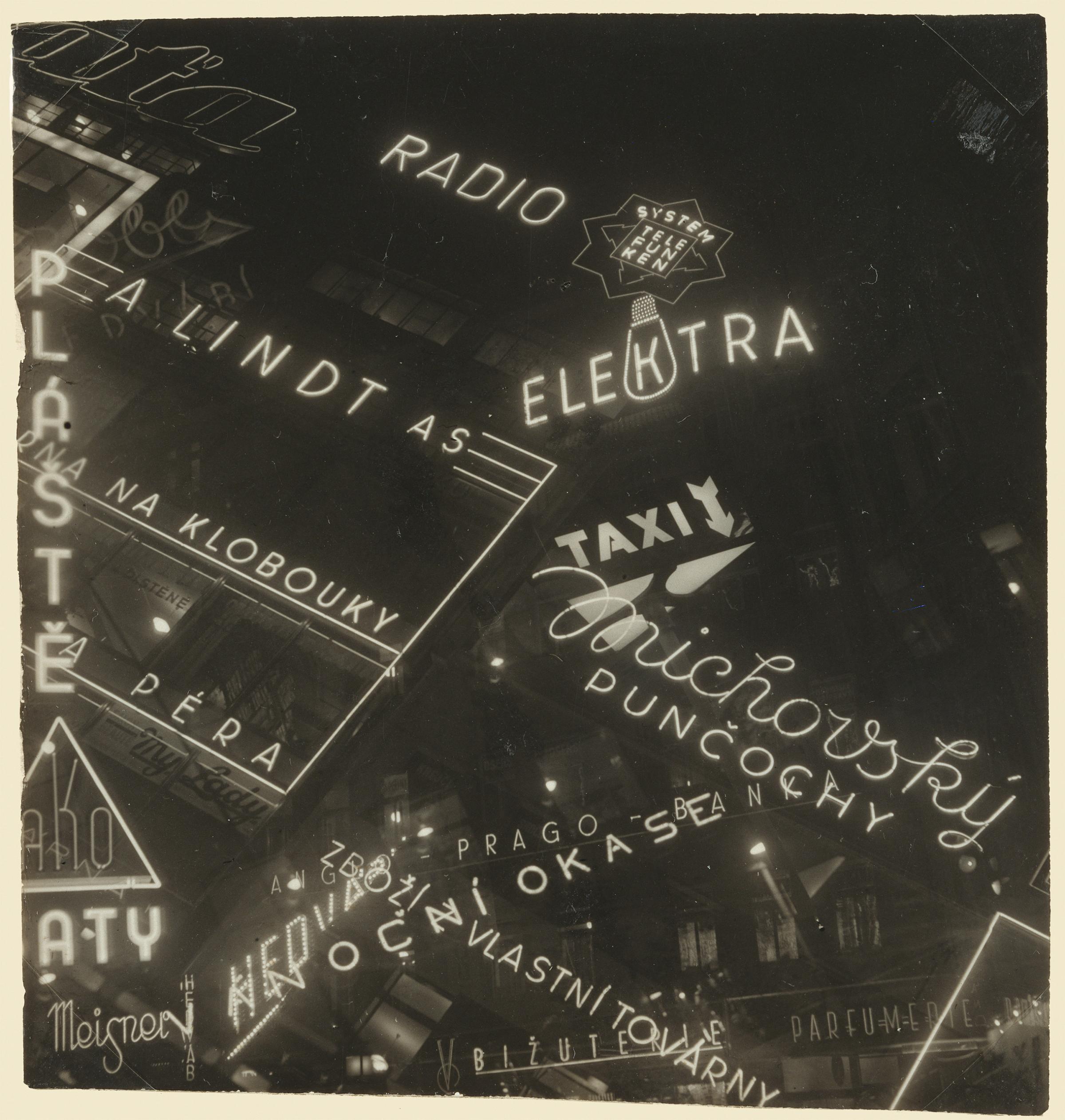

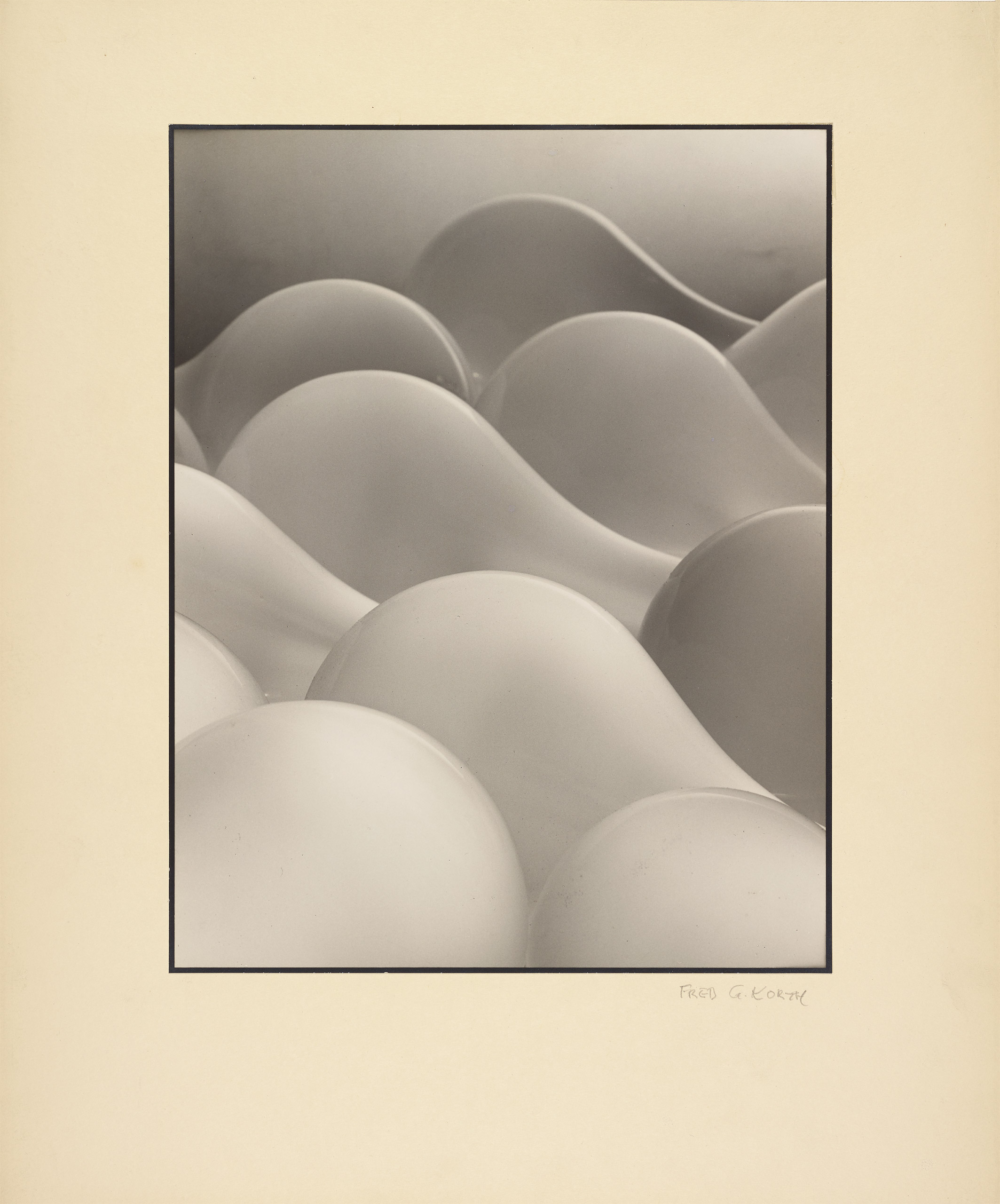

Some of the photographers turned their cameras directly toward these new light sources as subjects. The show at the J. Paul Getty Museum includes an abstracted still life of repeating lightbulbs by Fred G. Korth and a playful light painting by Barbara Morgan. Other photographers watched electricity take hold and questioned its implication in society. Japanese shooter Gen Otsuka balanced a level of acceptance and despair in his 1955 photograph of a majestic snow-peaked Mount Fuji obscured by waves of telephone lines sweeping across the landscape.

By looking backward as the two technologies advanced together, In Focus: Electric! builds a deeper appreciation for their relationship.

The exhibit, curated by Mazie Harris, assistant curator of photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum, will be on display until Aug. 28 in Los Angeles.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com