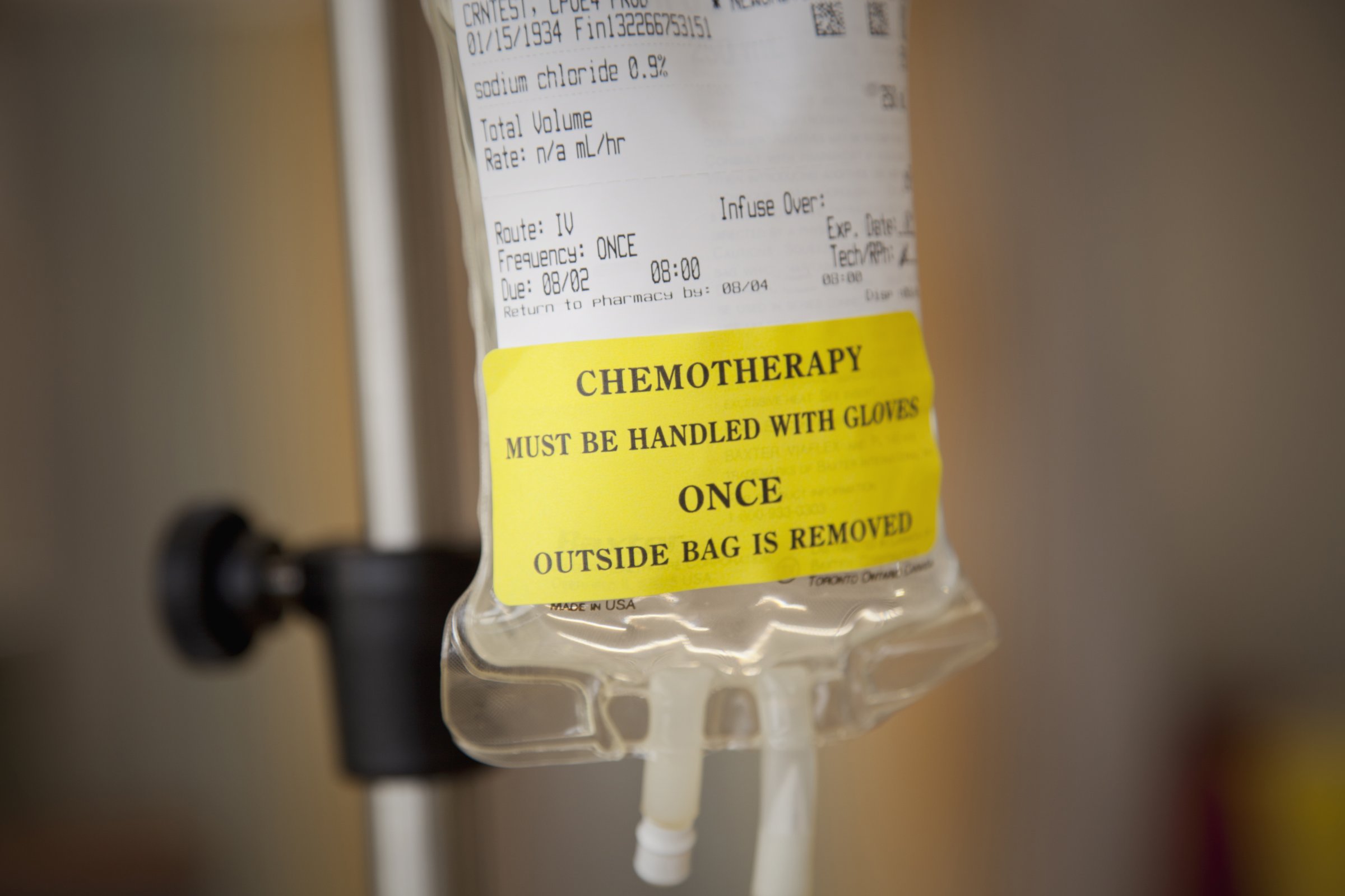

Treating cancer is all about elimination — surgery, radiation and chemotherapy are all designed to get rid of as many cancer cells as possible. But in a new study published in Science Translational Medicine, cancer doctors provide some strong evidence for turning the all-or-nothing strategy on its head.

A team led by Dr. Robert Gatenby, chair of radiology and co-director of the cancer biology and evolution program at Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, say that the current approach of using aggressive chemotherapy to try to eliminate every last cancer cell goes against basic evolutionary principles — rules that even tumor cells follow. “We tend to think of cancers as a competition between the tumor and the host, but at the level of the cancer cell, cancer cells are mostly competing with each other,” he says.

MORE: The Kind of Cancer That May Not Need Chemo

That means cancer cells making up a tumor aren’t all equal. A tumor can consist of numerous different types of malignant cells, and that’s supported by the fact that when they’re treated with something as powerful as chemotherapy, some cells will wither and die while others, even weeks or months later, will start to bloom again. Those are the cells that somehow, by a quirk of their mutations, happen to be resistant to the chemotherapy.

MORE: Early Stage Breast Cancer May Not Require Chemo

Gatenby and his colleagues investigated whether it would be possible to find the perfect balance of chemo that would kill off enough tumor cells but not be potent enough to encourage the resistant cells to come forward. They took cells from two different types of breast cancers and grew them in mice, which were then treated to standard chemo, or a modified chemo. In one scenario, the mice were given lower-dose chemo and then skipped sessions if their tumors shrunk, while in the other group, the animals were given continuous but gradually lower doses of chemo.

The group that got the continuous but gradually lower dose of chemo showed the best response in terms of slowing tumor growth. In up to 80% of the animals, their tumors continued to shrink to the point where they eventually didn’t need any additional chemotherapy at all. In contrast, tumors in the animals that received the standard high dose aggressive chemotherapy and those that skipped doses didn’t see their tumors shrink at all.

MORE: ‘Chemobrain’ Is Real — and More Likely With Certain Drugs

“These results surprised me a little,” says Gatenby. “I was concerned that although we might see some benefit, that we wouldn’t see a lot of benefit and that we may not be able to have an impact on the tumor because it’s growing so fast at the beginning.”

But the tapering of the chemo dose managed to find just the right balance between killing off the enough of the cancer cells and not activating the chemo-resistant ones. The tumor remained, but, says Gatenby, there’s evidence that the cancer cells became less active and slower-growing.

MORE: Why Doctors Are Rethinking Breast-Cancer Treatment

This signals a revolutionary way of thinking about cancer treatment, and introduces the idea that if it’s not possible to completely eliminate a tumor, which is not always possible, the next best thing is to control it. That requires a highly individualized therapy. Gatenby is hopeful that with enough patients taking advantage of this strategy in clinical trials, an algorithm may one day be built so that doctors can plug in certain characteristics from each person in order to calculate his proper chemotherapy regimen.

MORE: When Chemotherapy Does More Harm than Good

He’s testing the idea in a small group of men with prostate cancer who are getting frequent but lower doses of chemo to see how they do. “I think this is doable,” he says, noting that farmers who try to manage pest infestations in their crops use algorithms to help predict which pests will be most problematic and how to best to combat them.

“People who do pest management are way ahead of those who do cancer therapy,” he says. “I don’t think it’s unreasonable to think that eventually computer models can become highly prevalent for patients to help guide their treatment.” It’s just a question of asking people to be comfortable with the idea of living with a little bit of cancer in their bodies instead of doing everything they can to eliminate every trace of tumor. The science already shows it may be possible, but that psychological barrier may be harder to overcome.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com