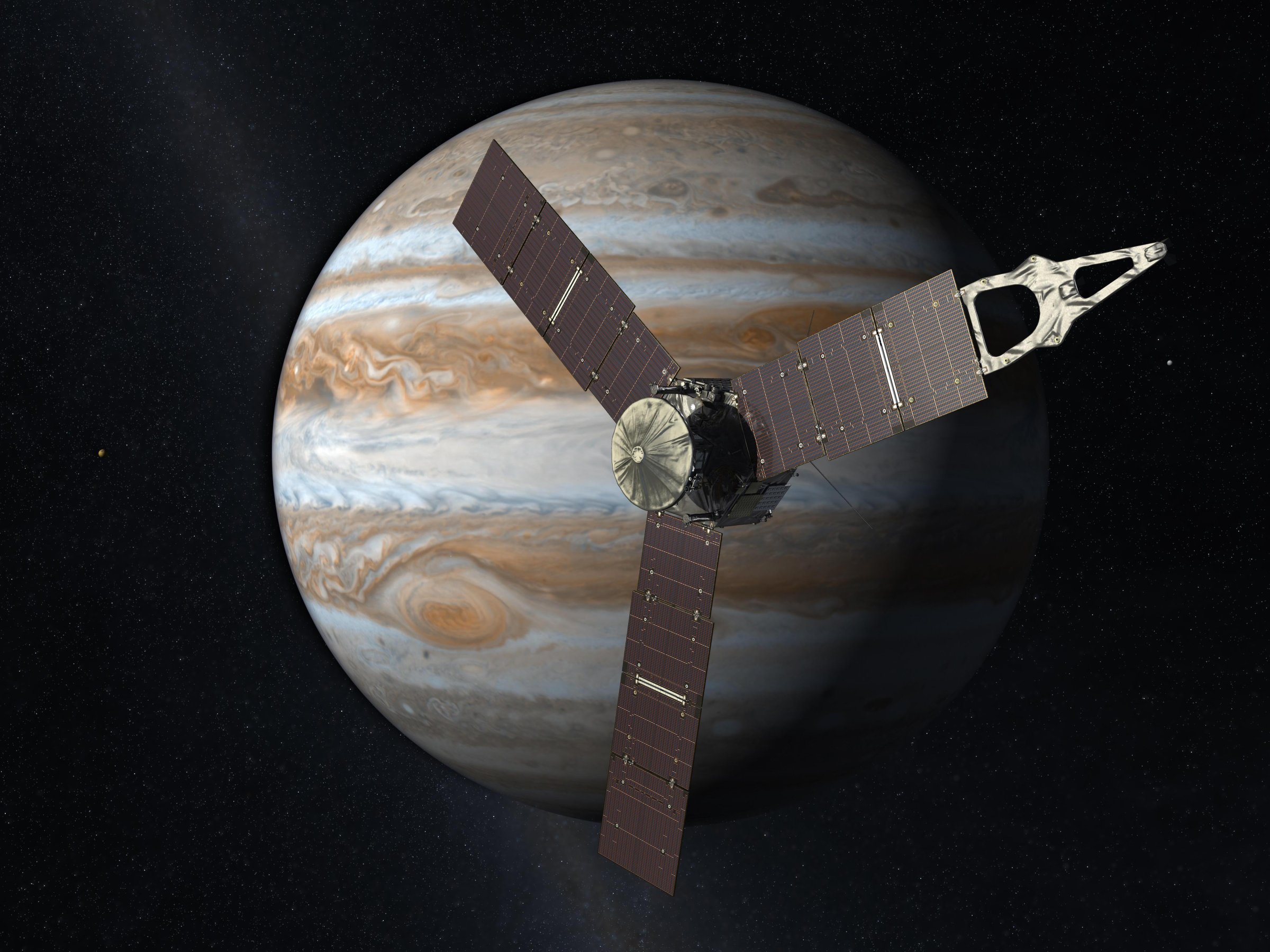

No matter how much traveling you did in the last five years, it’s a good bet you haven’t done as much as the Juno spacecraft. Launched from Cape Canaveral on a spiraling route out to Jupiter on Aug. 5, 2011, it has so far put 1.71 billion miles (2.75 billion km) on its odometer and has just 48 million miles (77 million km) to go before it gets where it’s going.

Juno won’t land on Jupiter, simply because there’s no such thing as landing on a gas planet that has no solid surface. It won’t plunge into the Jovian atmosphere either. That was a feat achieved only once before, when the Galileo orbiter arrived at Jupiter in 1995 and released a probe into the planet’s clouds. The high-tech projectile was not expected to last long and it didn’t—beaming back data for just 78 minutes before the planet’s massive internal pressure crushed it like a soda can.

Juno has a longer life to look forward to than that. When it arrives at Jupiter this July 4, it will begin at least a year’s worth of research, orbiting the planet 32 times at an altitude of 3,100 miles (5,000 km). Since NASA, smartly, tends to lowball its spacecrafts’ anticipated lifespans—which makes it easy for them to overperform—bet on Juno living well past its first birthday.

If it does, that will be a very good thing, because the spacecraft has a lot of work to do. Jupiter is often thought of as equal parts giant planet and failed star. Its atmosphere is about 90% hydrogen and about 10% helium with other trace gasses stirred in, which is very much like stellar chemistry. What it lacks—by a lot—is the same mass as a star, making it impossible for it to have ever achieved the critical pressure to ignite the fusion reaction that powers a sun.

But Jupiter’s almost-but-not-quite bulk makes it valuable for other reasons. Smaller planets, especially Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars—the rocky, terrestrial worlds—went through multiple changes early in their existence, as they were scorched by the sun, pounded by comets and asteroids and, in some cases, nearly demolished by passing planetesimals. Jupiter, far enough from the solar fires not to feel too much heat, and big enough simply to swallow up any of the smaller bodies that collided with it, survived more or less unchanged—carrying 4.5 billion years of cosmic chemistry in its clouds. Studying Jupiter’s atmosphere is like reading the tree rings of the solar system itself.

For that reason, Juno’s onboard instruments will search Jupiter’s atmosphere for water, hydrocarbons and other possible organic materials that were present in the early solar system. They will also probe the deep clouds looking for a possible solid core, which will provide clues to how all such gas giant planets form. The spacecraft will also study the behavior of what is known as Jupiter’s metallic hydrogen—ordinary hydrogen under such extreme pressure that it begins to conduct electricity like a metal, perhaps giving rise to the planet’s magnetic field.

Unlike Galileo, Juno will circle Jupiter in a vertical—or polar—orbit, which will allow it to avoid the worst of the planet’s intense radiation belts. This means it will also beam home the first close looks at the Jovian poles.

More important, space-watchers hope, Juno may help stoke the fires of public interest in the Jovian system as a whole. Jupiter, surely, is not home to life. But three of its moons—Ganymede, Callisto and especially Europa, which is known to be home to a deep ocean of mineral-rich water—might well be, and a mission to Europa is already in NASA’s development pipeline. The planet that didn’t quite become a star, might just have much more important things to reveal.

For more about Jupiter’s mysteries, please tune into my new podcast, It’s Your Universe, (available on iTunes and Stitcher), which each week takes you on a tour of a new destination in our solar system. We’ve visited Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars, and on Thursday, March 3, we’ll arrive at Jupiter.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com