For five painful days last year, Jeb Bush struggled to answer the obvious question facing anyone with his last name: Would he repeat his brother’s fateful decision to invade Iraq?

When Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly asked the inevitable question, Bush said he backed up his brother. “I would have, and so would have Hillary Clinton, just to remind everybody,” Bush said. As the media swarmed and donors fretted, the presidential candidate ham-handedly struggled to clean up his unforced error, ultimately declaring that knowing what he knows now he would have made a different decision than the 43rd President.

The events illustrated everything that was wrong about another Bush candidacy. The uncertainty. The role of his dynasty. The limits of money over personalities. His unfamiliarity with an unforgiving modern news cycle that rewards gaffes over well-thought policy. The fear of letting his famous family down.

That was in May. He never really recovered.

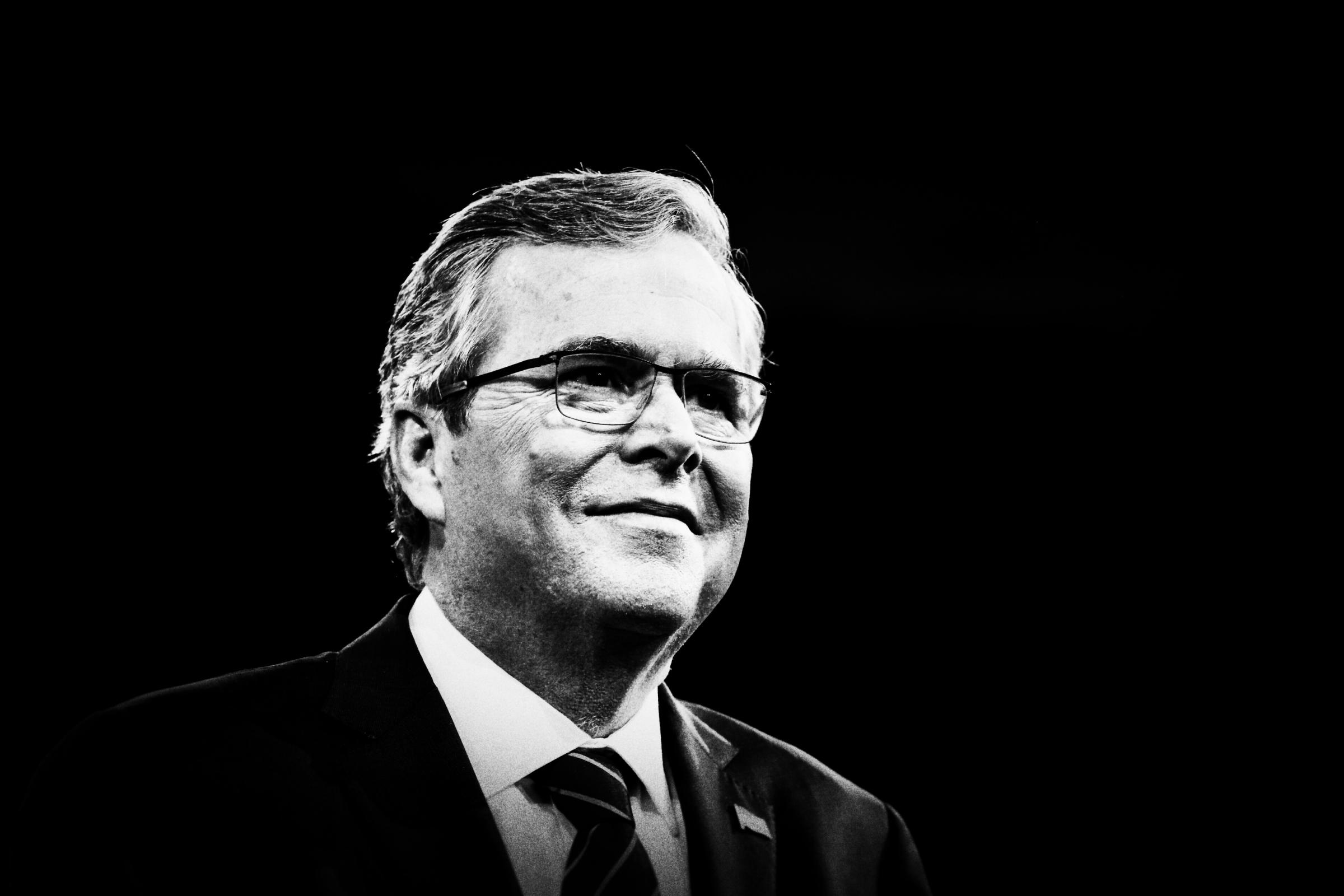

In the end, John Ellis Bush was not the candidate Republicans were looking for in 2016. He didn’t even live up to the hype, years in the making, that this scion of one the most powerful families in Republican politics could be a stellar leader.

And, with a whimper, the former Florida governor packed up his campaign Saturday night and went home to Miami. In typical Jeb Bush fashion, he would want to know what they could have done differently and where they went wrong. But first, he just wanted to exit a race for the GOP nomination that has defied precedent, civility and, at time, belief.

At a time when experience was a vulnerability rather than a resume line, Bush insisted on running a policy-centric campaign. It was a year that saw bluster overtake substance, and Bush refused to shift. “In this campaign, I have stood my ground, refusing to bend to the political winds,” he said before leaving the stage, tears visible in his eyes. His insistence on running his campaign his way proved his undoing. While rivals mastered clipped sound bites, he held forth on policy. When reporters tried to goad him into questions about politics, he defaulted to wonkdom. If a voter took the time to attend his town halls, he owed it to them to give a thoughtful answer.

“This way my guy,” said Tiffany Pritchett, a veteran of George W. Bush’s White House and Commerce Department. “I’m shocked Trump did as well as he did, respectfully.” The Davidson, N.C., resident spent her week knocking on doors in South Carolina for Bush, and she found herself getting more and more emotional about the idea of Trump sitting in the same office as George W. Bush. “I just wonder,” she said, “what happens now.”

One year ago, Bush appeared to be doing everything right. He raised more than $120 million. He hired veteran operatives and experienced firms. He had his father’s and his brother’s loyal donors and advisers, while upstarts like Ben Carson and Trump were seen more like punch lines than players. He tested the limits of campaign-finance laws and directly helped a friendly super PAC that, through the end of last week, spent almost $96 million to help Bush.

Yet Bush seemed to hate everything that the modern campaign required, including the reporters who followed him everywhere. He refused for months to discuss politics, dismissing them as “process questions” and therefore not worth his time. “Ten-yard penalty, loss of down,” was his default reply. He never really grasped that the national political media was not the same as a statehouse press corps in Tallahassee.

Bush struggled to understand Trump or the political phenomenon that drove the New Yorker to back-to-back primary wins in New Hampshire and South Carolina. In recent months Bush refocused his campaign on taking on the bombastic front-runner, only to be branded repeatedly as “low energy” and see the poll leader insult his Mexican-American wife before the nation. Trump reopened the wounds of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and blamed George W. Bush. “You cannot insult your way to the presidency,” Bush repeated time and again, to little avail.

Bush also marveled at the role of social media and at times seemed incredulous that any of it mattered. For instance, after a long day of campaigning in January, he sat down with TIME to talk about his bid. He was as guarded but thoughtful as ever. Yet as he wrapped up, an aide guided him over to one of the campaign’s videographers to do a quick video for the campaign’s social media accounts. “That’s right. You’re the propagandist,” he said of his own staffer. He simply didn’t understand why anyone would bother with goofy videos rather than footnoted policy proposals.

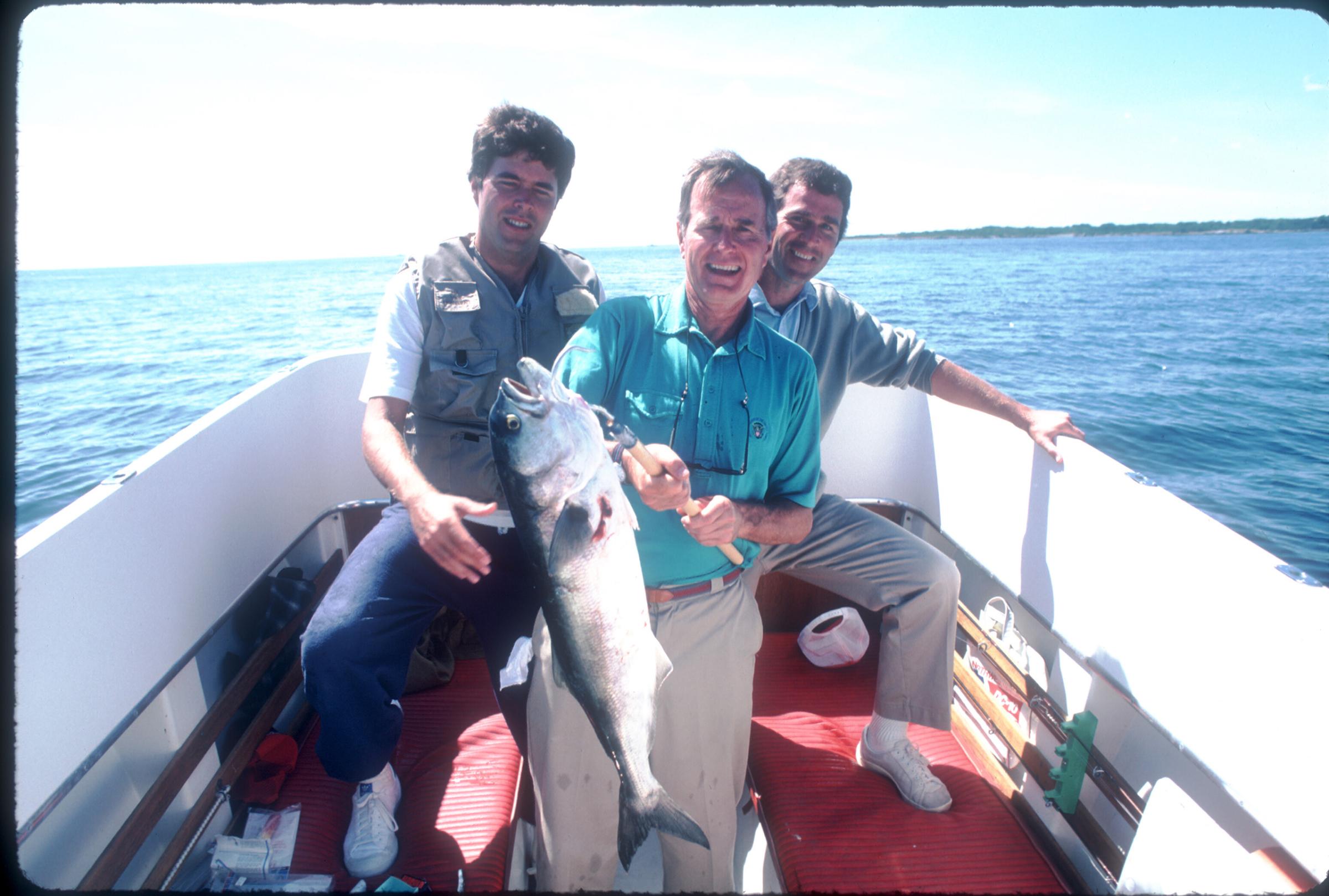

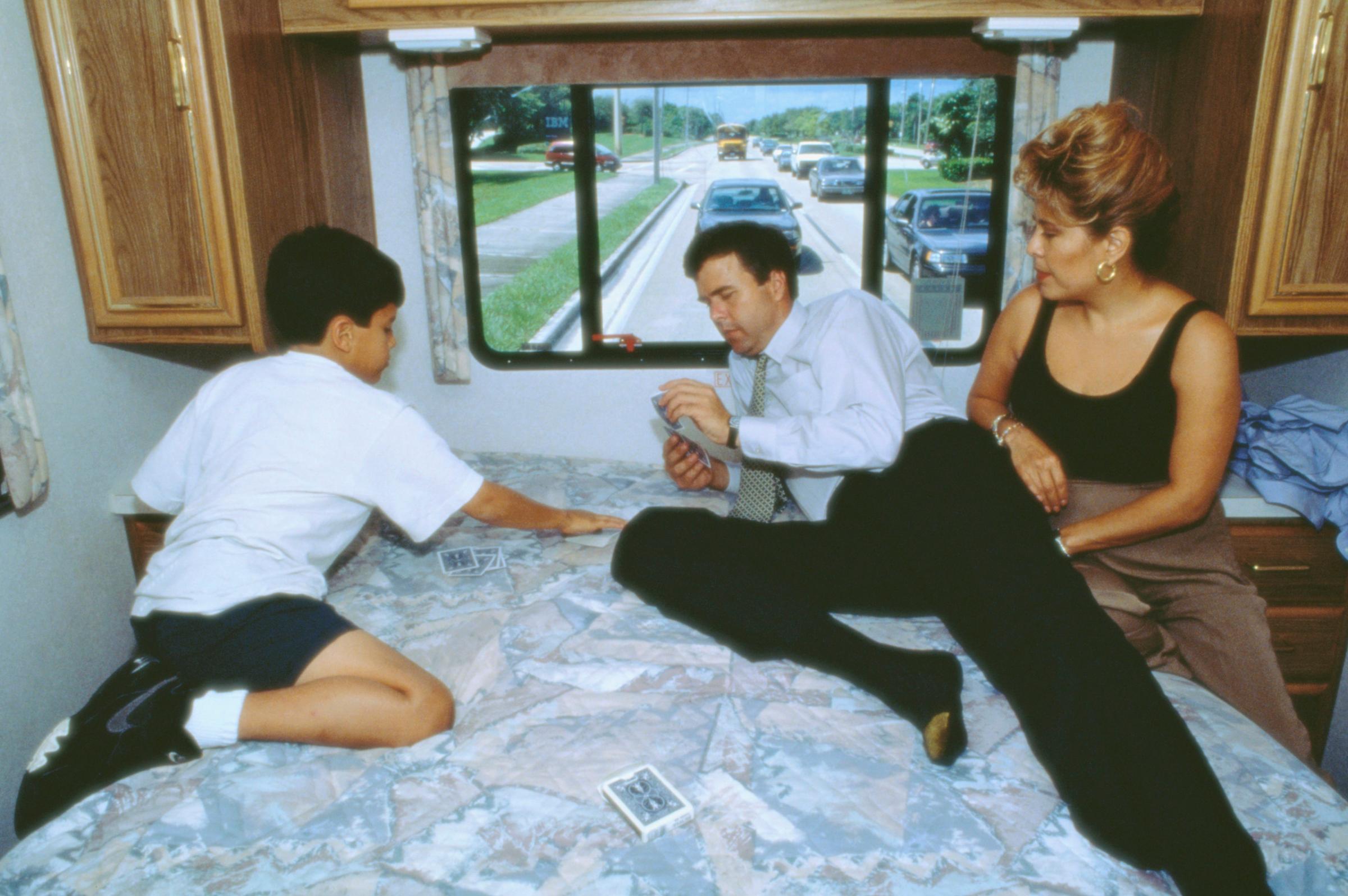

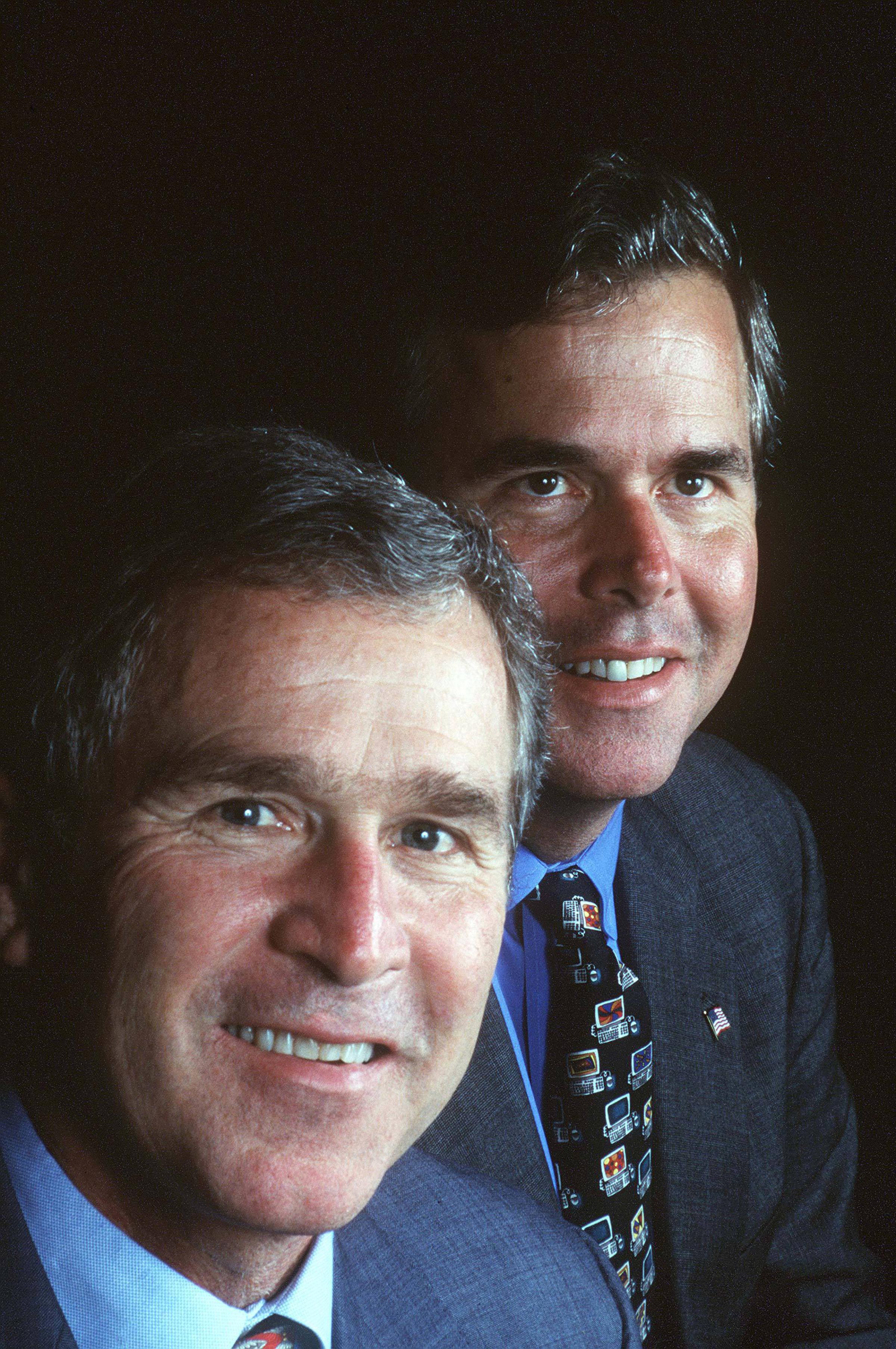

In recent days, Bush had started to realize the end was near. It was obvious even to his inner circle that they were heading here, and many booked two tickets: home to Miami or onward to Nevada. His rally with brother George W. helped turn out thousands of South Carolina voters who still held the former President in high regard. But the event also was a reminder which son of George H.W. and Barbara Bush was the natural political talent, and which one was the wonk. Jeb was left an also-ran at his own campaign rally. His deep family connections made him a credible candidate — before they contributed to his downfall. He was a member of the political elite when voters have been tuning in for a reality-show star.

“I had hoped he would have done better,” said Sadie Hartman, a 75-year-old Bush supporter from Columbia, S.C., who was only slightly surprised Bush dropped out. “I guess the country was tired of the Bushes, and a third one might have been too much.”

Her husband added his voice to the chorus that Bush’s exit turns the campaign into a three-man race between Trump, Cruz and Rubio. “Trump’s going to win,” Jim Hartman said. Hartman said he doesn’t understand why voters backed Trump, but Trump will have his vote in November if he’s the nominee. “I just hope he brings better-tempered people in around him, and I hope Jeb Bush is one of them.”

Given how sourly Bush is about the state of American politics at the moment, it’s unlikely he is ready to join a Trump Cabinet. Trump single-handedly magnified all of Bush’s weaknesses and midwifed a political movement that, to date, has proved that the traditional of order of politics is upended. It also might leave the country ungovernable.

“With strong conservative leadership, Republicans can win the White House,” Bush said, promising to help. But who? And to what end?

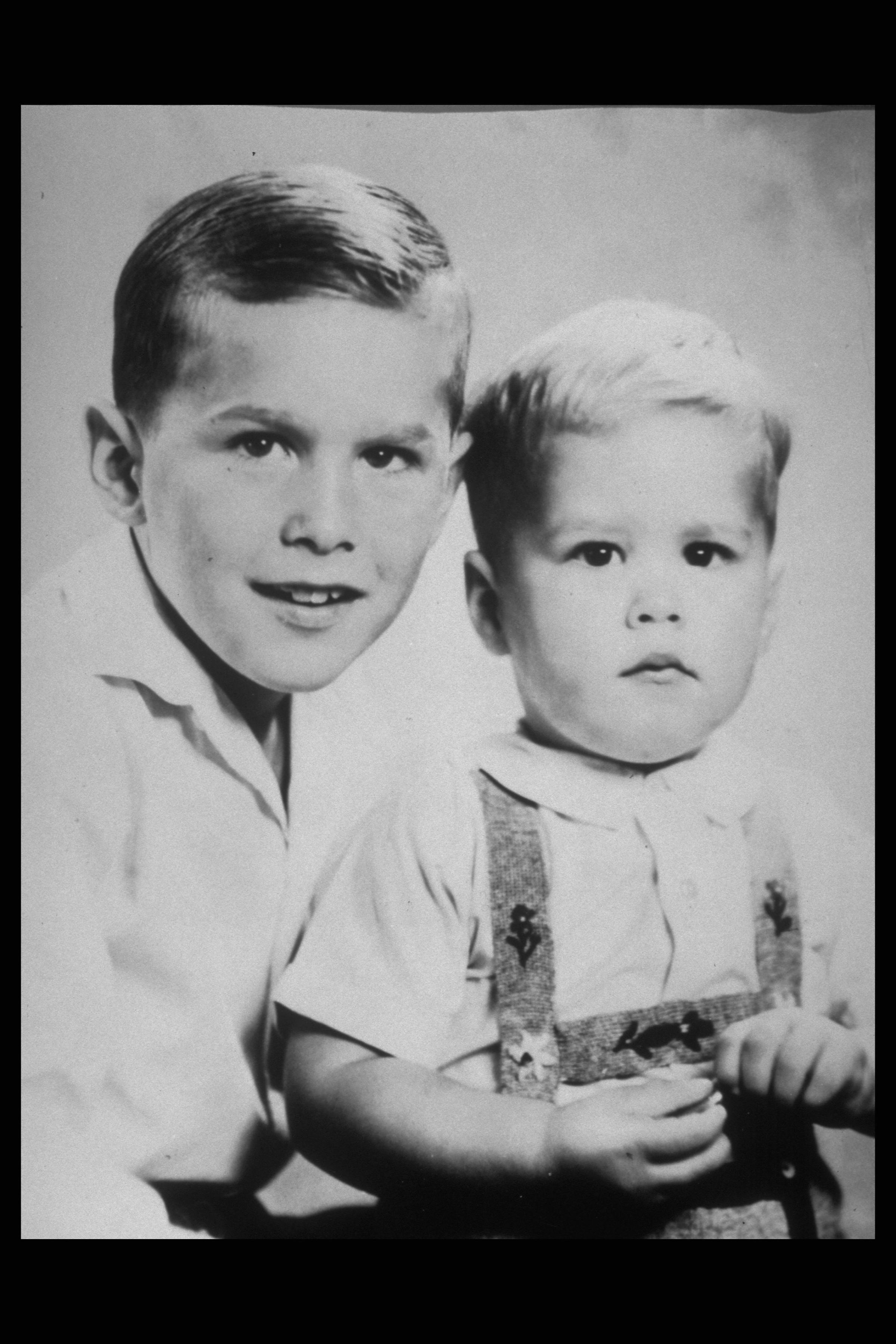

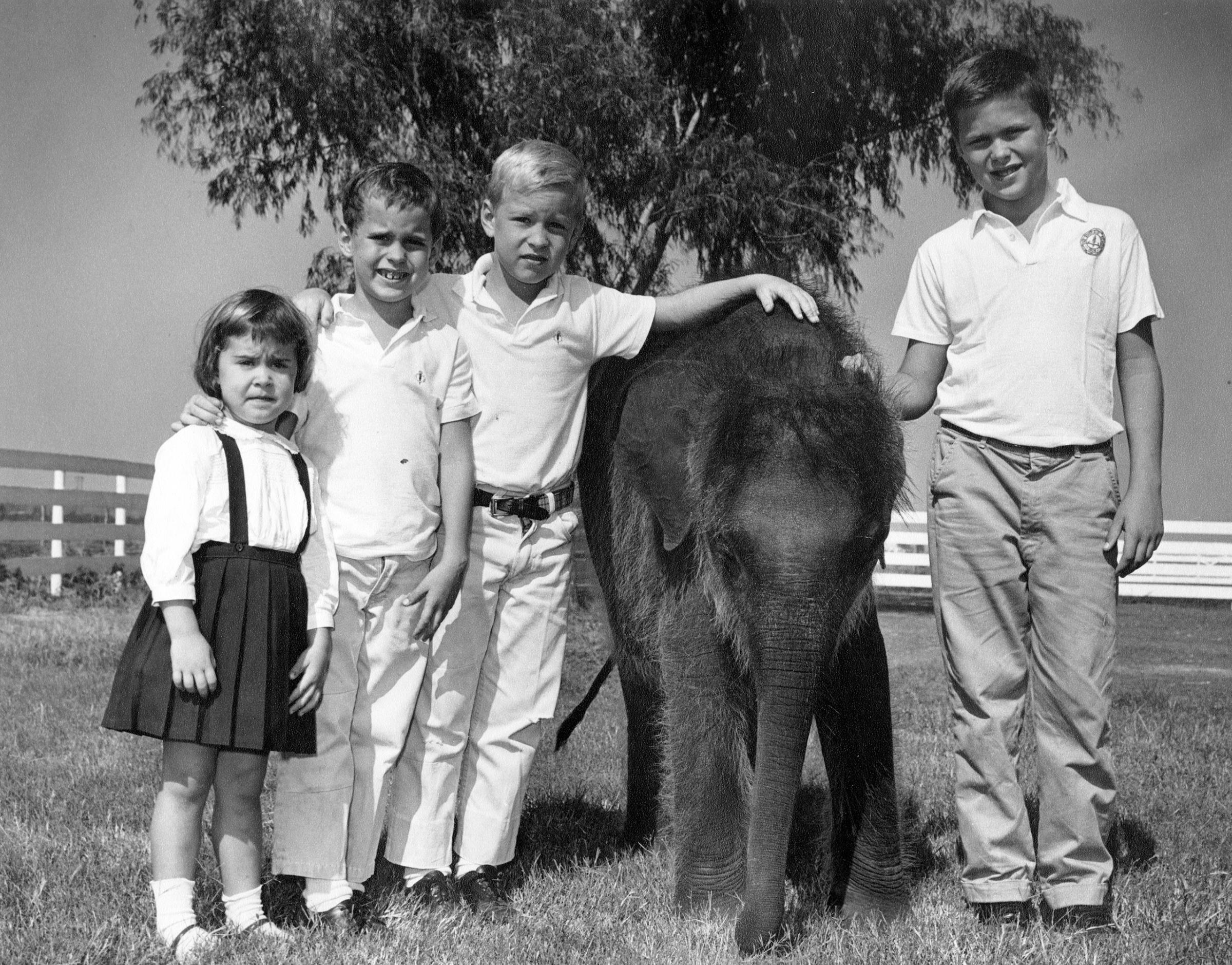

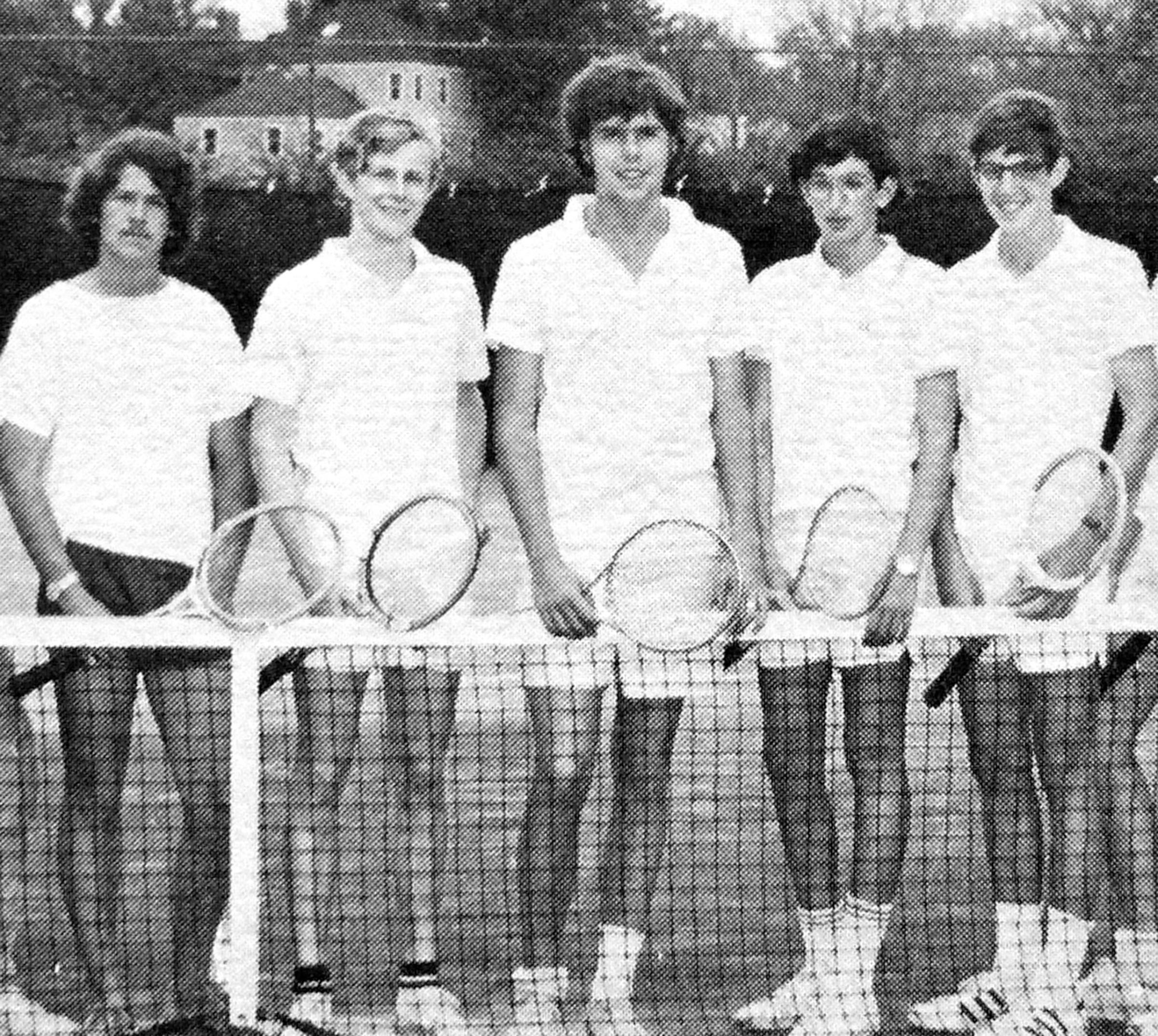

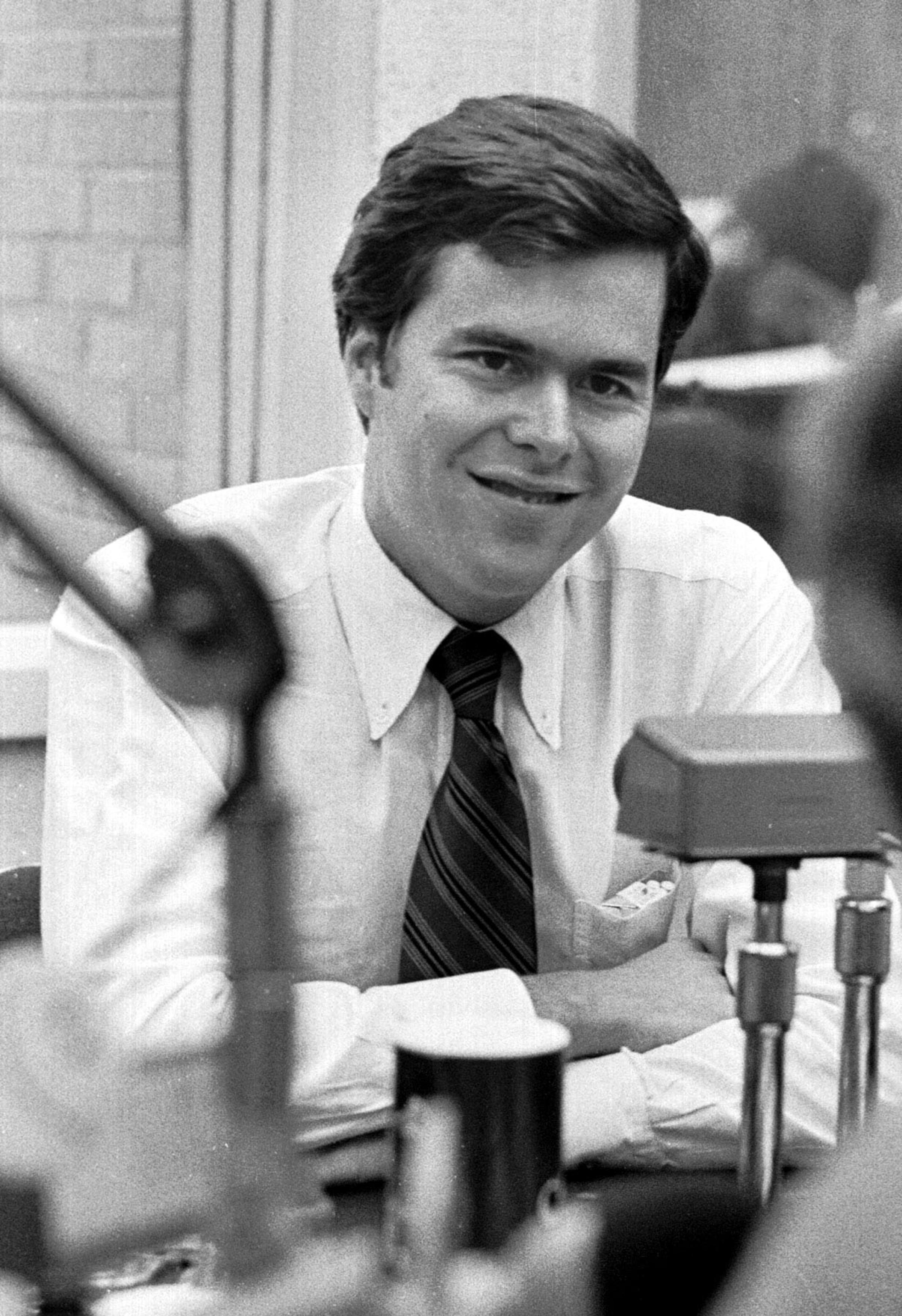

See Jeb Bush's Life in Photos

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Philip Elliott / Columbia, S.C. at philip.elliott@time.com