Ever since Ted Cruz emerged as a national figure by provoking the federal government shutdown of 2013, some older Americans have noticed that both his appearance and the cadence of his voice call to mind Sen. Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, the man who terrorized leftists for four meteoric years from 1950 through 1954. The resemblance is a vague one: Cruz is younger, shorter and slimmer than McCarthy, and McCarthy held forth in the era of grainy black and white newsreels and television, when politicians were not yet coiffed and made up like film stars.

In recent weeks, however, as Cruz wages a national campaign for the Republican nomination, another similarity worth noting has emerged: Not content with attacking Marco Rubio for voting for the President’s authority to negotiate new trade pacts, Cruz’s campaign displayed a faked photograph of Rubio shaking hands with President Obama on a new website. Queried on Thursday, the Cruz campaign did not deny the fake, but accused Rubio of simply trying to divert attention from his liberal record. Rubio’s campaign responded that it was a “deceitful” move. But, though Photoshop editing software has come a long way in recent years, Cruz isn’t the first to use that tactic.

Joseph McCarthy was elected to the Senate in the Republican sweep of 1946—the same year in which both Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy were elected to the House of Representatives. After four exceedingly undistinguished years in that body, he became a national figure in February 1950 when he announced that 206 card-carrying Communists were working in the State Department. Although the accusation was without foundation, the time was ripe for it. Several spies had been uncovered within the U.S. government, Communists and other leftists were already under attack in many American institutions, and China had fallen to Communism the previous year. The leadership of the Republican Party was desperate after the loss of four consecutive presidential elections, and encouraged McCarthy to keep beating the Communism drum.

As it happened, McCarthy joined the anti-Communist fight too late to be effective: most actual Communists had already been driven out of the government, and the Senator never uncovered a single one himself. But his accusations appealed to various segments of the public, and he tried to make sure that anyone who dared oppose him would pay a heavy price.

The charge that the State Department was harboring Communists could not be ignored, and a subcommittee of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee opened hearings to investigate it. The subcommittee chairman was one of the most powerful men in the Senate: four-term Senator Millard Tydings of Maryland, a conservative Democrat who in 1938 had survived President Roosevelt’s attempt to defeat him in a primary. In the midst of the hearings, North Korea attacked South Korea, and the United States went to war against international Communism. But the Tydings report, issued a few months later, found McCarthy’s charges to be without foundation. McCarthy decided to get his revenge.

McCarthy’s Washington office plunged head first into Tydings’ re-election campaign in Maryland. It distributed literature accusing Tydings of displaying insufficient zeal in fighting Communism, and McCarthy violently attacked not only Tydings but the whole Democratic establishment, arguing that it was handing the nation and the world over to Communists. McCarthy had quickly built up a national following that included some Texas oilmen and conservative Catholics like Joseph P. Kennedy, and he funneled money into the campaign of Tydings’ Republican opponent, John Marshall Butler.

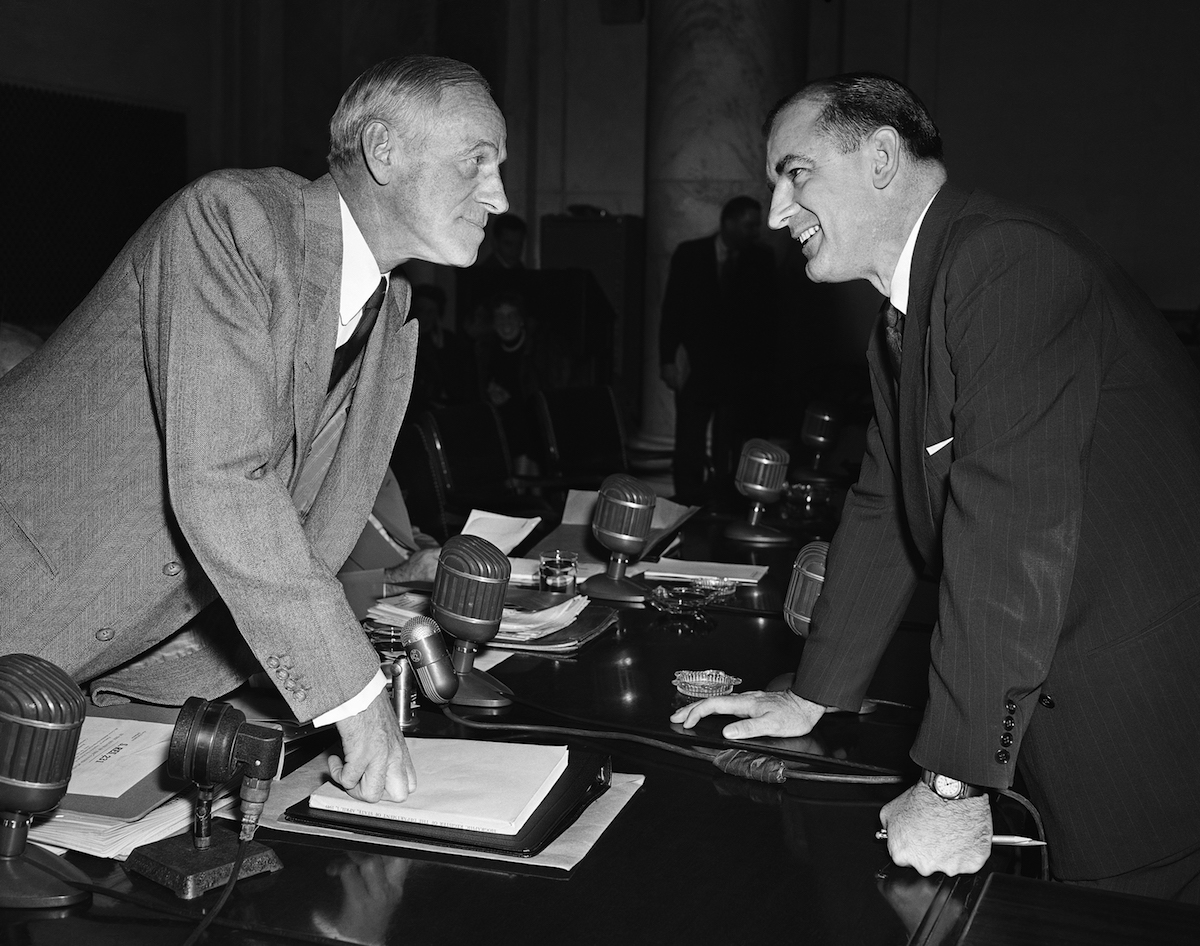

Then, in the last week of the campaign, with the race in the balance, McCarthy’s people helped distribute a “composite” photograph that appeared to show Tydings in conversation with none other than the head of the tiny American Communist Party, Earl Browder. The closest the two men had ever gotten, ironically, was when Browder testified before Tydings’ committee during the investigation of McCarthy’s charges, but no real photo would convey the intimacy McCarthy wanted to suggest. When the photo surfaced in the last week of the campaign, Butler disclaimed any knowledge of how it had come to be. Though Tydings spoke up about the photo being a dirty trick, it was too late: once the photo was out there, it could not be taken back.

Butler defeated Tydings comfortably—a shock to many observers—and almost no one in the Senate dared stand up to McCarthy for the next two years.

Our political world is much more fragmented today than in 1950, and almost no one lumps their enemies together under a simple label like “Communists.” But in this year’s wide-open contest for the Republican nomination, to have ever sided with the President on anything has become a potential liability—as Ted Cruz underlined this week. For Cruz, as for McCarthy, any deviation from true belief means complete apostasy. For example, Cruz has even turned on Chief Justice Roberts, for whom he clerked, for his refusal to strike down Obamacare.

Differences between the careers of McCarthy and Cruz reflect changes in our national politics. The Republican establishment was initially delighted by McCarthy in 1950 but they inevitably turned against him when he attacked the Eisenhower Administration, leading to his condemnation by an overwhelming vote of the U.S. Senate, then under Republican control. Cruz on the other hand never made any pretense of cooperating with his party’s leadership, defying them in his 2013 effort to shut down the government, and constantly attacking mainstream Republicans as collaborators with President Obama. And yet Cruz has become a major presidential contender—something at which McCarthy never even seemed to aim. In this turbulent era of American politics, the Republican Party candidates have declared war not only against the Democrats, but against each other as well.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

David Kaiser, a historian, has taught at Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, Williams College, and the Naval War College. He is the author of seven books, including, most recently, No End Save Victory: How FDR Led the Nation into War. He lives in Watertown, Mass.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com