Like most great heroes, Jesse Owens had his own creation myth — which is not to suggest that it was untrue. By his own reckoning, he was more or less molded by the tragic events and desperate circumstances of his childhood in Alabama and then Ohio. Born on September 12, 1913, in Oakville, Alabama, James Cleveland Owens was the tenth and last child of Henry and Mary Emma Owens. He sometimes said later in life that his early childhood in Alabama was essentially happy, because he had no idea how poor he was. But there was nothing genteel about the Owenses’ brand of poverty. For sharecroppers like Henry Owens, every day was filled with struggle. If there was too much rain or not enough, if there was too much frost, a crop could fail—and then it would take all his resourcefulness merely to feed his family. For the Owenses, everything but food, shelter, and the simplest clothes was a luxury that simply could not be afforded — even medical care.

For Jesse Owens, the defining moment of his youth—the story he told over and over — revolved around a fibrous bump he noticed on his chest the day after he turned five. At first he thought it would just go away. But within a few days he could see it growing and feel it pressing against his lungs. Eventually, J.C., as his parents called him, could no longer bear the discomfort. He told his mother. Not always the most reliable narrator of his own life story, Owens later reconstructed the subsequent conversation he claimed he overheard between Henry and Emma Owens:

“We’ve got to do something,” Emma said to Henry.

“You took one off his leg once, Emma.”

“But this one’s so big. And near his heart.”

“Emma —”

“Don’t say it, Henry!”

“I’m going to say it. If the Lord wants him —”

All these years later, it is impossible to say who had the greater talent for melodrama, Henry Owens, in his fatalism, or Jesse Owens, in his storytelling. Certainly it is possible that Jesse misrepresented Henry’s exact words, but undoubtedly Henry was a man who had come to expect the worst in any situation.

The son of former slaves, Henry Owens had grown up in Oakville, not far from Georgia but a world away from the nearest big town, Decatur, which is 20 miles to the northeast. He spent most of his life scratching out a living as a sharecropper. By most accounts, he lived in mortal fear of his landlords — and other white men. For southern black men of his generation, deference to white men was nothing less than a survival imperative. Between 1882 and 1902 there were more than one hundred lynchings each year in the United States, the vast majority perpetrated in the South. All his life, Henry Owens avoided making eye contact with whites.

Emma Owens was as ambitious as her husband was timid. Against all odds, she held out hope that her children’s lives would be less bleak than hers. She had grown up in less desperate circumstances than her husband. She knew that there was a world outside Oakville, even if Henry didn’t. From the beginning, Jesse took after his mother, not the father who had long ago learned to keep his expectations low — even when the subject was his son’s health.

A few nights after little J.C. brought the growth on his chest to his parents’ attention, he was lying in bed. His mother came to him and said, “I’m going to take the bump off now, J.C.” The Owens family could not afford the services of a physician.

As Henry Owens wept quietly in the corner, Emma Owens sterilized a kitchen knife over a flame. Then she started cutting into her son’s chest. J.C. bit down hard on a leather strap. No sound penetrated the strap, but tears flowed down his cheeks. Dark, thick blood started pouring out of him. Emma moved the knife around the edges of the lump, searching for its contours, trying to determine its size and consistency. It was bigger than she had thought. It seemed to her as if the blade was inching too close to J.C.’s heart. Still, she kept cutting. Finally it was done. She extracted the gelatinous lump, and in its place was a hole the size of a golf ball, not oozing but spurting blood. Emma tried to stop the bleeding, but for days it continued.

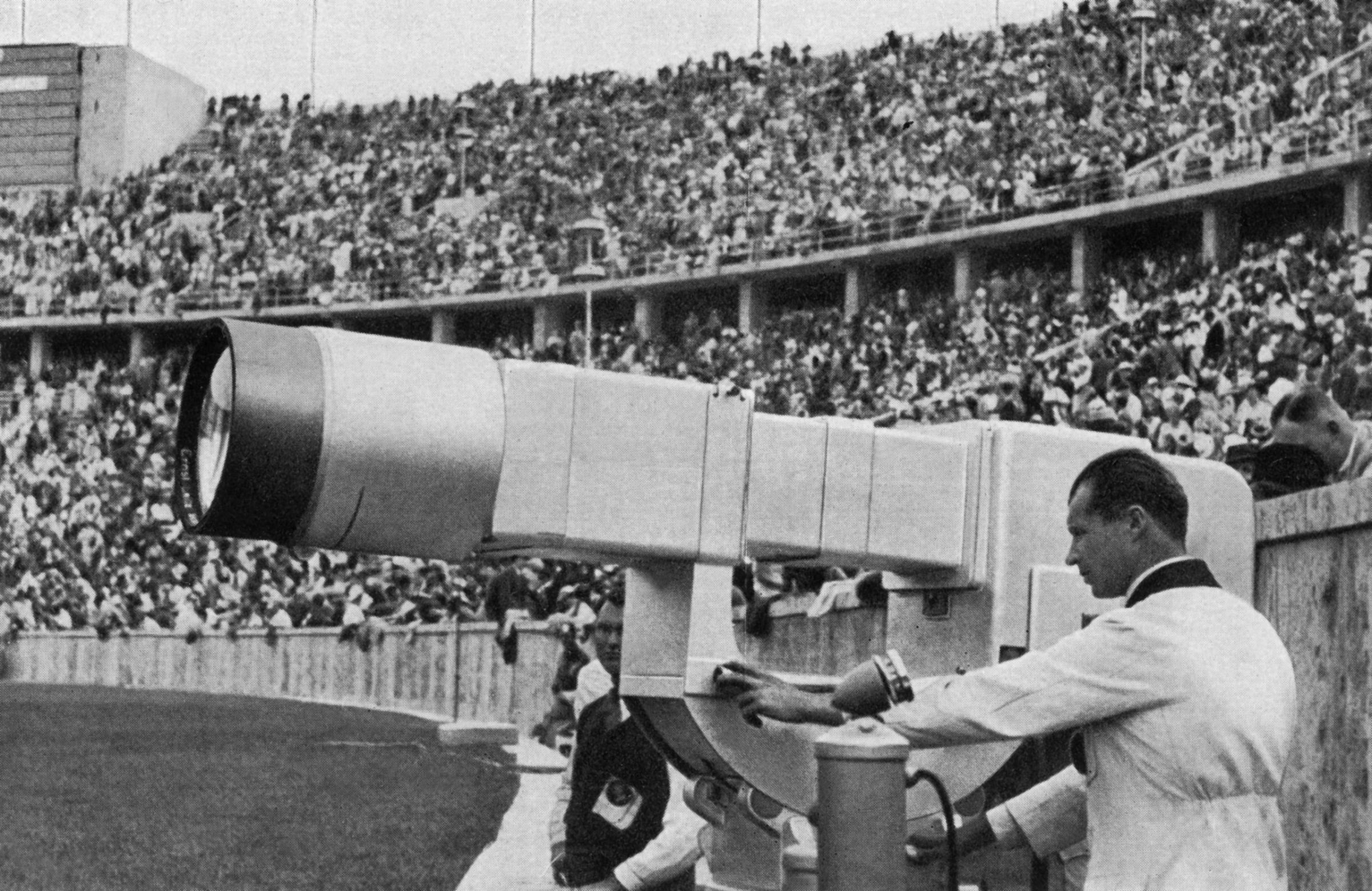

See the Controversial Drama of Adolf Hitler’s 1936 Summer Olympics

Three nights after the makeshift operation, J.C. rose from his bed and walked to the front door of the tiny house. He later said that he could hear his father praying outside. “Oh, Lord Jesus,” Henry said, “Please, please, hear me. I know you hear everything, but this saving means everything. She’ll die if he dies — and if she dies, Lord, we’ll all die — all of us.”

As he listened to his father’s desperate prayer, J.C. was getting weaker. “My body was emptying of blood,” he later wrote.

“He’s my last boy,” Henry continued, still on his knees. “J.C.’s the one you gave me last to carry my name. She’ll die if you take him from me. She always said he was born special.”

Then J.C. walked into the night, into his father’s arms. “Pray, J.C.,” Henry Owens said. “Pray, James Cleveland.” Together, father and son knelt and prayed.

Within minutes, Jesse Owens later wrote, the bleeding stopped. The growth was probably a fibrous tumor.

As an adult, Owens usually described his hardscrabble youth in Oakville as beyond miserable — an endless cycle of poverty, hunger, and humiliation. But on other occasions he said that he had been happy in Alabama. Knowing nothing of the world beyond Lawrence County, he never considered himself deprived. “We never had any problems,” he said. “We always ate. The fact that we didn’t have steak? Who had steak?”

J.C. and his six brothers and three sisters were forced to spend about one week each year picking cotton, but most of the time they were free to play out in the fields that Henry Owens farmed.

Religion was a constant for the Owens family. They were devout Baptists, regular congregants at the Oakville Missionary Baptist Church, where Henry was a deacon. During the week it was the schoolhouse for Oakville’s black children. J.C., though, like most of his siblings, wasn’t there enough to learn much more than how to read and write. More often he was out in the fields, running barefoot, running because he loved it and because there was little else to do.

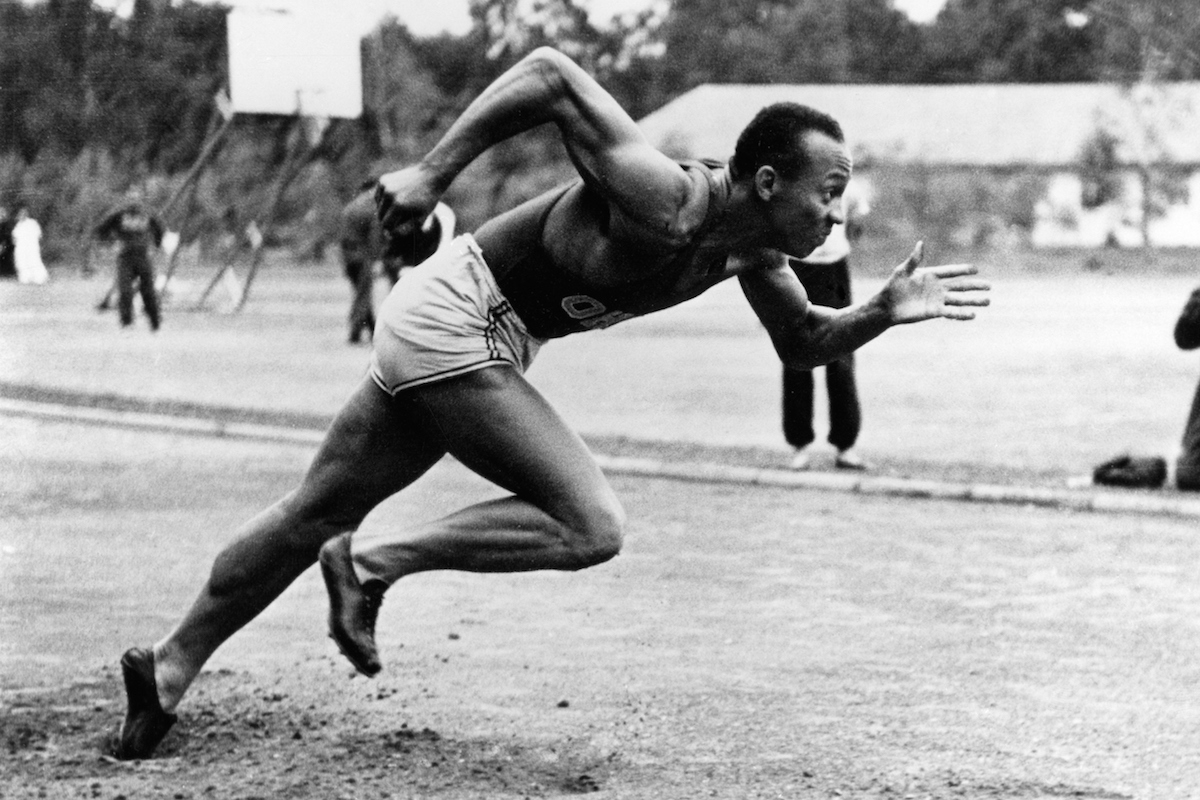

“I always loved running,” he said about his youth in Oakville. “I wasn’t very good at it, but I loved it because it was something you could do all by yourself, all under your own power. You could go in any direction, fast or slow as you wanted, fighting the wind if you felt like it, seeking out new sights just on the strength of your feet and the courage of your lungs.”

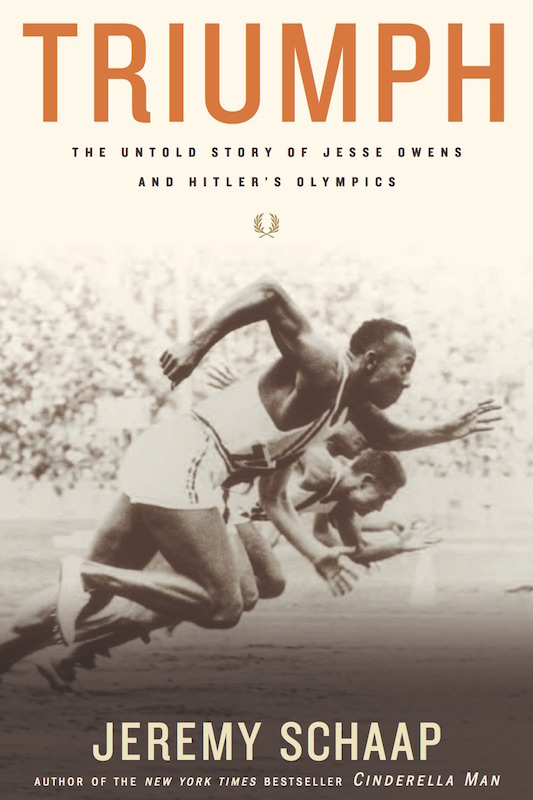

From Triumph by Jeremy Schaap (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). Copyright © 2007 by Jeremy Schaap. Reprinted by permission of Houghton

Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com