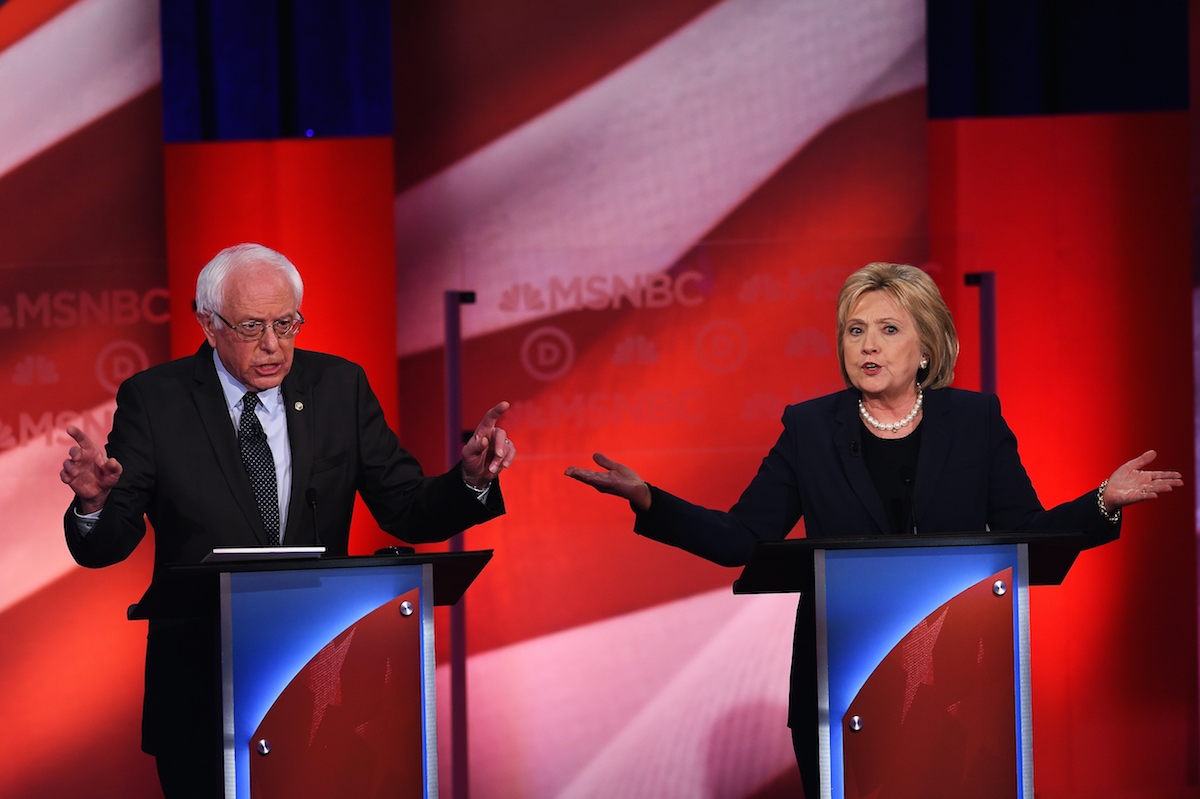

At the Democratic debate between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders on Thursday night, the candidates’ discussion of the issues branched into slightly unusual territory: semantics. In a discussion that started with the question of whether Clinton was progressive enough to meet the Democratic Party’s needs, she called Sanders “the self-proclaimed gatekeeper for progressivism” and characterized his definition of “progressive” as so tough to meet that “it’s really caused [her] to wonder who’s left in the progressive wing of the Democratic Party.”

It was a thorny debate—but, it turns out, the question of what it means to be progressive in America is even more complicated than that.

“Historians don’t have a definition [of ‘progressive’] and we’ve argued for years over whether there is such a thing,” says Charles Postel, an expert on the Progressive and Populist movements who teaches history at San Francisco State University.

Yes, there was a specific Progressive Party (a.k.a the Bull Moose Party, which backed Theodore Roosevelt’s 1912 run for the White House) and a specific Progressive Era, during the first 15 or 20 years of the 20th century. But the ideas that gave that era its character—labor reform, farm reform, women’s rights, health reform, antitrust regulation, child-labor restrictions and more—had begun to spread decades earlier and didn’t stop evolving when World War I came, even if new era had otherwise begun. “This is something that historians now talk about as the ‘long Progressive Era,'” Postel says.

What’s striking about the more narrowly defined Progressive Era, Postel adds, is not so much that reformers had new ideas during that time but that they were remarkably successful in getting things done. And with so many activists making strides, it’s hard to say who should get credit for starting things or which causes were most central. But, while it’s hard to pinpoint a beginning and end for the Progressive Era, it’s a bit easier to list the reforms that set it apart. The power of corporations to influence government was a major concern for the classic progressives—in that way, “many progressives [of that time] sound like Bernie Sanders sounds today,” Postel says—as was a need for social improvement, which meant integrating immigrants into society, improving conditions for children, ending political corruption and cleaning up cities, among other efforts.

Postel argues that today’s use of the word “progressive” isn’t substantively different from the modern use of the word “liberal,” which has its own, perhaps even more complicated history. (Here’s the short version: a 19th-century liberal was someone who advocated for free markets, but during the 1930s, when the Progressive Era was still relatively fresh in the nation’s minds, proponents of the New Deal started using the word “liberal” to describe their policies, though many of them were connected to Progressive ideas. During the Reagan years, “liberal” acquired a bad reputation and eventually “progressive”—with a lower-case “p”—came back.) But there’s a logic to the Democratic candidates wanting that linguistic link to the early Progressives.

First of all, Postel says, it’s worth noting that today’s politicians who claim the progressive mantel do share a lot with their forebears. Sanders’ respect for Eugene Debs, the socialist leader of the Progressive Era, who believed that the Progressive Party had stolen the Socialist platform, is well known. As for Clinton, the historian sees a strong connection between the political stances and personal lives of the candidate and Jane Addams, one of the foremost female activists of the Progressive Era. And the policies that mark a modern candidate as progressive are generally ones that would be recognized by the reformers of a century ago. (The parallel isn’t perfect, but that’s for the best: “Progressivism in the early 20th century tended to be deeply racist, either overtly, in the sense of Woodrow Wilson who really was a segregationist, or through just negligence,” Postel says. “Today racial justice is an integral part of progressivism.”)

So, given all that history, are today’s Democratic candidates truly progressive? Is one more progressive that the other? Who was right on Thursday?

If you ask Postel, both candidates were correct, but in slightly different ways.

“There’s no question that Bernie is something to the left of Hillary on a series of questions, but I think Hillary also has a point that there is no sharp line of who is a progressive and who is not,” he says. Teddy Roosevelt, for example, was the iconic Progressive president, a supporter of national health insurance and an enemy to corporate trusts—but he was also “a pretty strong supporter of any war that he could find to get behind.”

Finding a single politician who can tick every progressive box is impossible today, but it’s been just as impossible since the movement’s earliest days. So, Postel says, though Sanders’ positions are more classically progressive, Clinton’s take on the difficulty of defining the word is historically accurate, too.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com