Gordon Parks is one of America’s most celebrated photographers. He is also one of the most misunderstood. Museums and galleries around the world have celebrated him as the creator of some of the 20th century’s most iconic images. Yet to appreciate only his achievements as an artist is to underestimate his importance as a documentary photographer and journalist. The photo essays Parks produced, primarily for LIFE magazine from the 1940s to the 1970s, on issues relating to poverty and social justice, established him as one of the era’s most significant interpreters of American society. His peers were writers like Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin as much as they were LIFE photographers like Margaret Bourke-White and W. Eugene Smith. Visual Justice: The Gordon Parks Photography Collection at Wichita State University, an exhibition at the Ulrich Museum of Art (for which I served as senior project advisor), examines photographs from six of his most powerful photo essays, enriching our understanding of his work in its historical context.

In interviews and in his memoirs, Parks, who passed away in 2006, always emphasized that there was “no special black man’s corner” for him at LIFE. He was as comfortable photographing celebrities, Paris fashions and Benedictine monks as he was an impoverished family in Harlem and Black Panther Party members in Oakland. Photographs which are far removed from pressing social concerns make up part of Visual Justice. Yet, as its title suggests, the photo essays that grapple with social justice are at the heart of the exhibition.

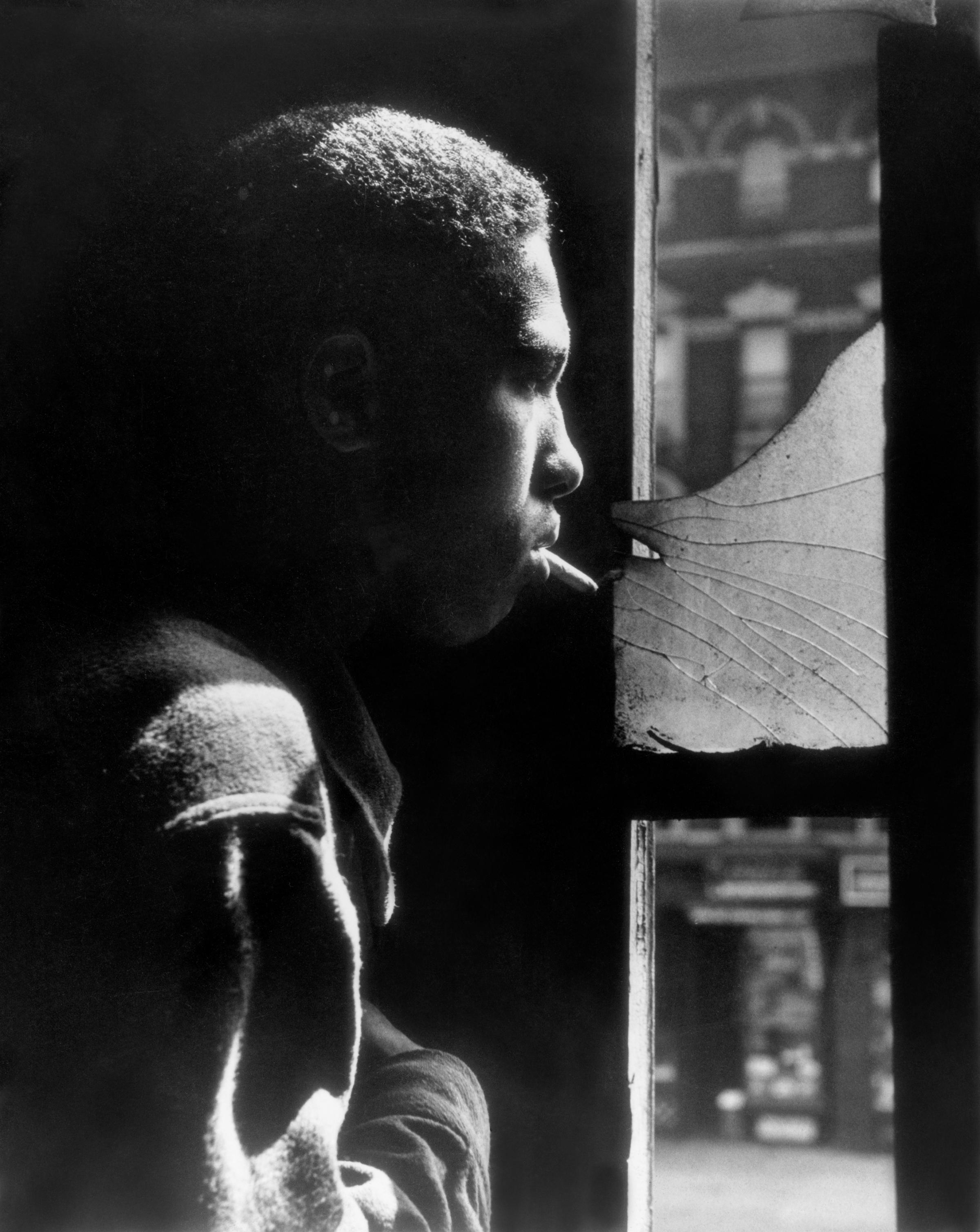

“Harlem Gang Leader,” from 1948, was Parks’ second major assignment for LIFE. Parks spent a month with 17-year-old Red Jackson, the teenaged gang leader of the story’s title, and other members of the Midtowners gang. His goal, he once said, was to show that juvenile delinquents were teenagers whose lives could be turned around if the right social service agencies intervened. As Russell Lord, a curator at the New Orleans Museum of Art, has shown, Parks discovered that when he turned in his film to LIFE’s laboratories, he ceded control of his story to the magazine’s editors. While the tone of the published photo essay was generally sympathetic to Jackson and the other gang members, it emphasized violence and slighted the potential for rehabilitation. Parks learned his lesson. His eagerness to write the text that accompanied his future photographs reflected his desire to assert more control over their message.

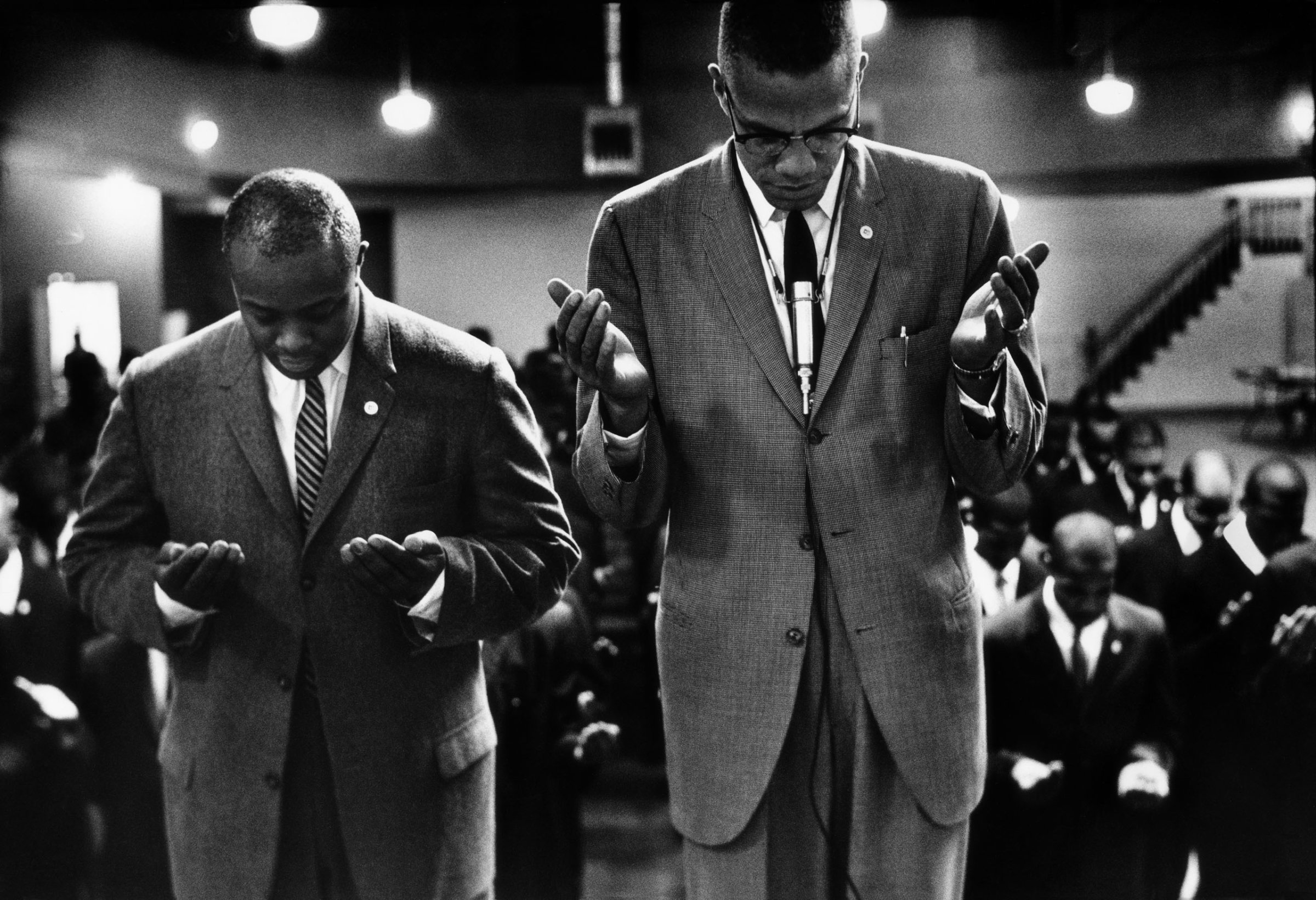

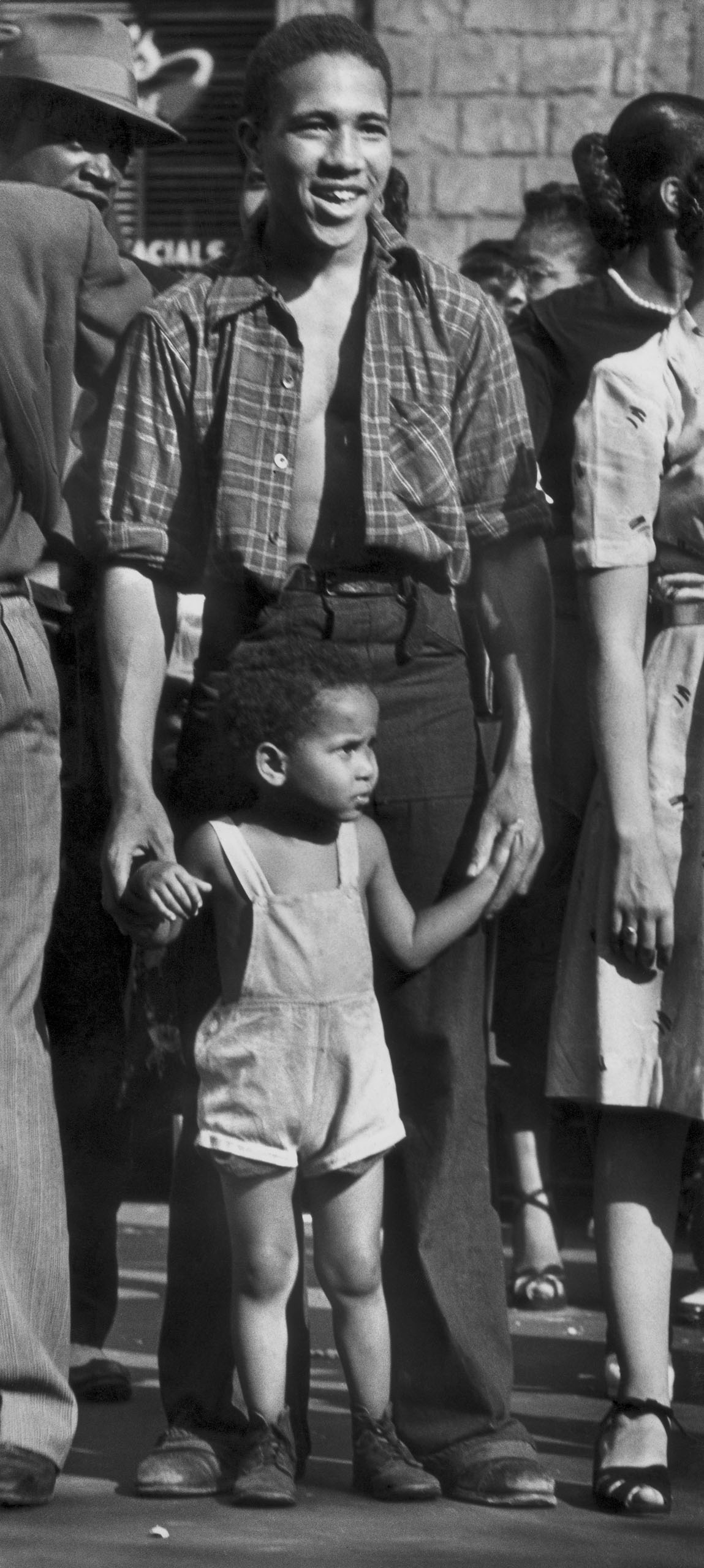

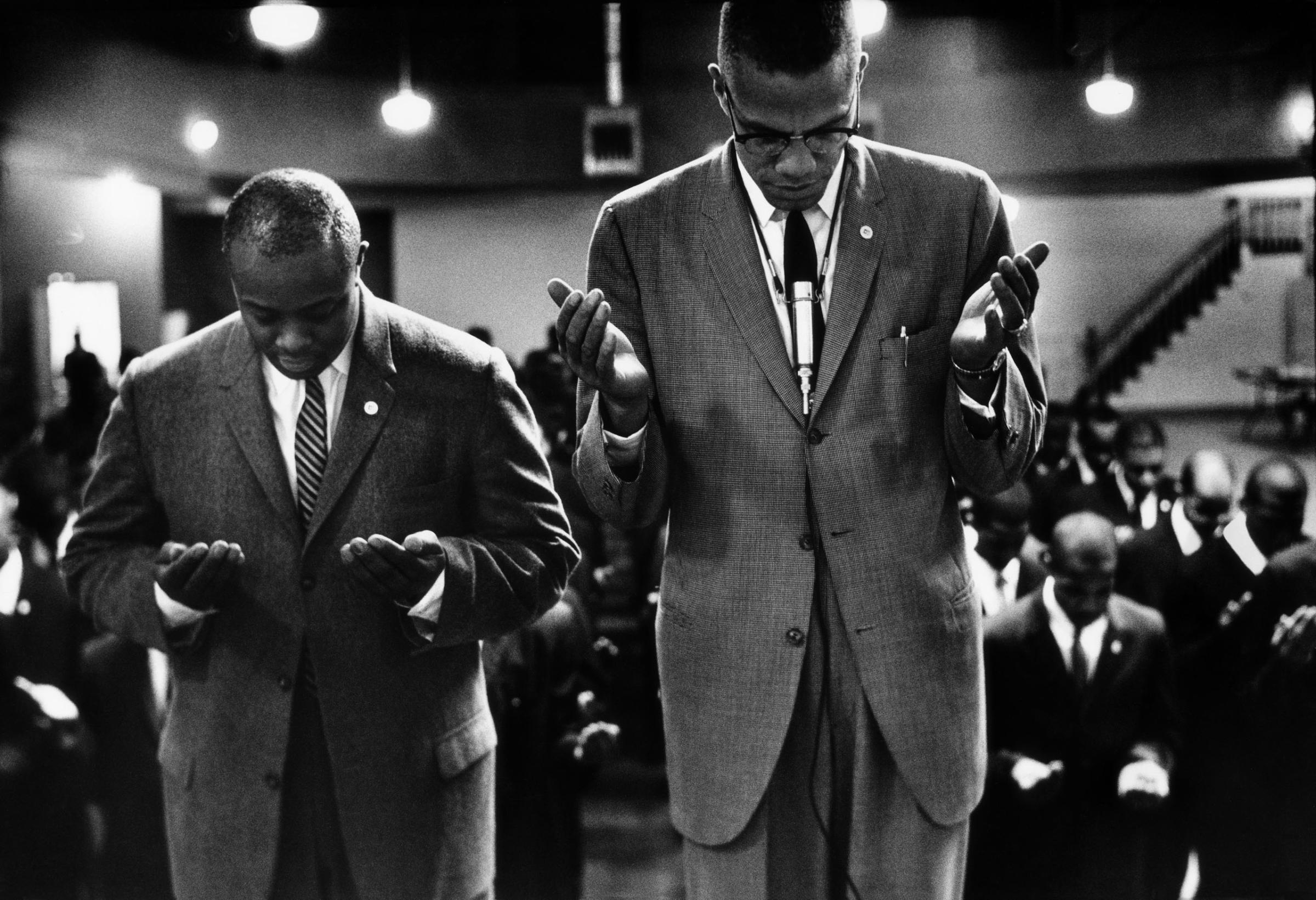

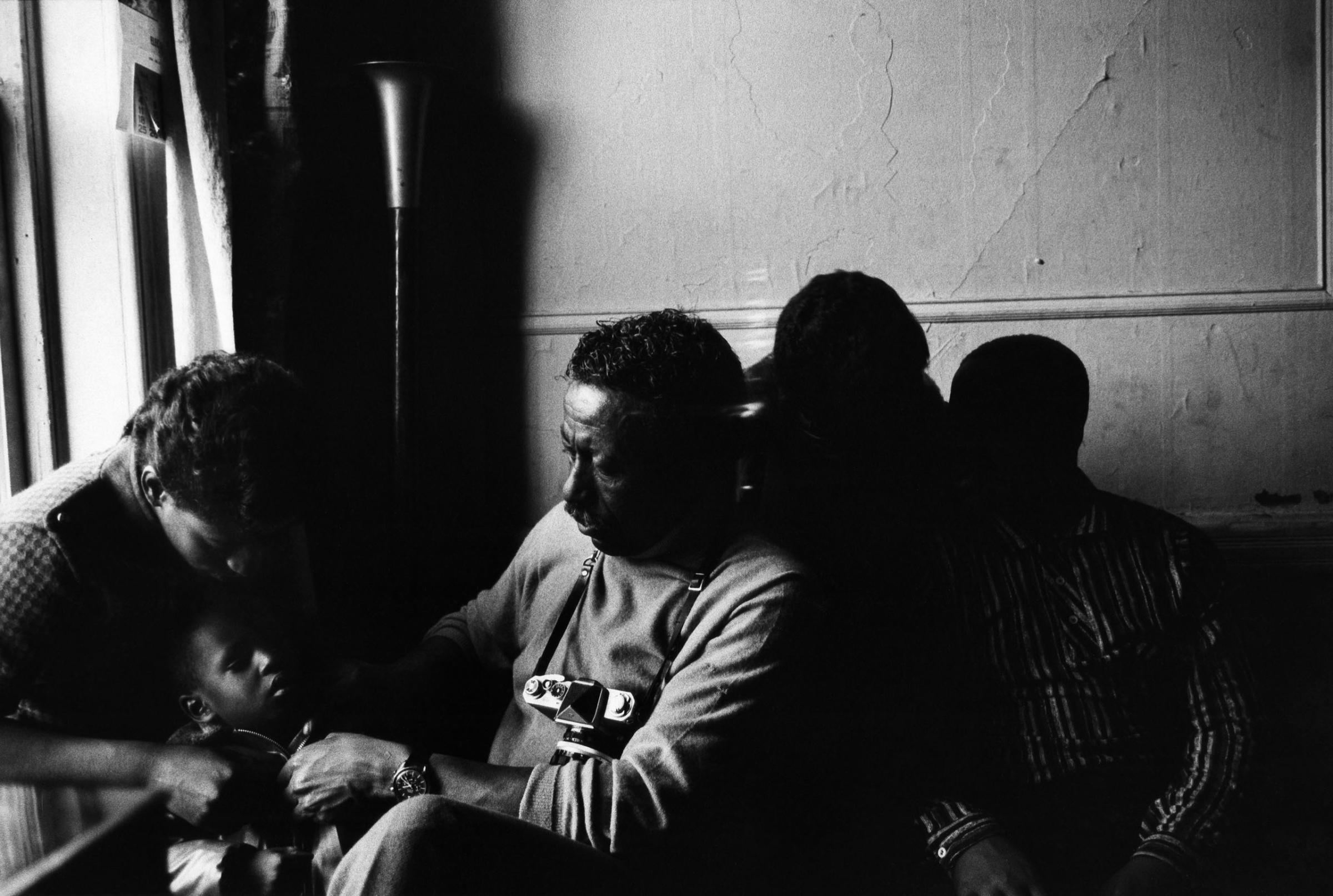

Parks was one of LIFE’s best known and most admired photographers by the time that “The White Man’s Day Is Almost Over,” his photo essay about the Black Muslims, appeared in 1963. His star status allowed him to exert more control over his story than he had over previous stories. The result was a nuanced and finely textured photo essay that challenged conventional wisdom about the group. Visual Justice contains 30 of the photographs that Parks made, most never before published or exhibited, during the three months he worked on the assignment, traveling from New York to Los Angeles, with stops in Chicago and Phoenix. They portray a religious community that is far different from the dangerous collection of fanatics that television and the press usually depicted. They emphasize the importance of family, faith and disciplined, peaceful protest. Many of the images show Malcolm X, who was Parks’ guide through the world of the Black Muslims, in a variety of roles—spokesman, prayer leader, amateur photographer.

In 1968, Parks’ editors challenged him to show them (and LIFE’s readers) the roots of the anger and frustration that were then so evident in the African American community. In “A Harlem Family,” his subjects were the Fontenelles, a family whose lives were battered by menial jobs, poor schools and wretched living conditions. Their plight tortured Parks, who often found himself buying food for them. Darkness and despair pervade the photographs. Plaster peels from the walls of the family’s apartment; children huddle under blankets for daytime warmth; the father stares blankly into a void.

In the pages of LIFE, “A Harlem Family” began not with a photograph, but with a prose-poem by Parks. Speaking in the voice of black America, he asked his readers, whom he understood to be white, to “Look at me. Listen to me. Try to understand my struggle against your racism.” Parks hoped to provoke a response, and he got it. Hundreds of letters, now preserved in the Gordon Parks Papers at Wichita State University, poured into the magazine’s offices. Some were hostile, blaming the Fontenelles for their own misery. Many were sympathetic, however, expressing concern and asking how to help the family. Readers sent money. Their contributions were enough, in fact, that when LIFE topped them off, the Fontenelles were able to move out of Harlem and into a new apartment in Queens. But tragedy followed them. In the spring of 1969, LIFE reported that a fire had broken out in the family’s new home and that the father, Norman, and a son, Kenneth, had died. In his memoirs, Parks described the overwhelming guilt he felt for their fate. He stayed in touch with them until the end of his life, offering them a hand whenever they needed it.

Parks was a man of many pursuits—photographer, novelist, poet, memoirist, filmmaker, composer. But he is most remembered as a photographer. And while some of his images live on because they delight the eye with their beauty, others endure because of the way that they touched the hearts and minds of millions of LIFE’s readers and changed, if only just a little, the course of American history.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com