Correction appended, Jan. 29 2016

For the second straight day, all but three of Detroit’s public schools were closed because of teachers calling in sick in a coordinated protest over pay. The mass “sick-outs” forced the cash-strapped district to close 94 of its 97 schools Tuesday.

The latest protest follows news that $48.7 million in emergency funding given to the school system by the state would run out by June 30. The loss of emergency funding would prevent teachers from being paid and force the cancellation of summer programs, according to the Detroit Free Press.

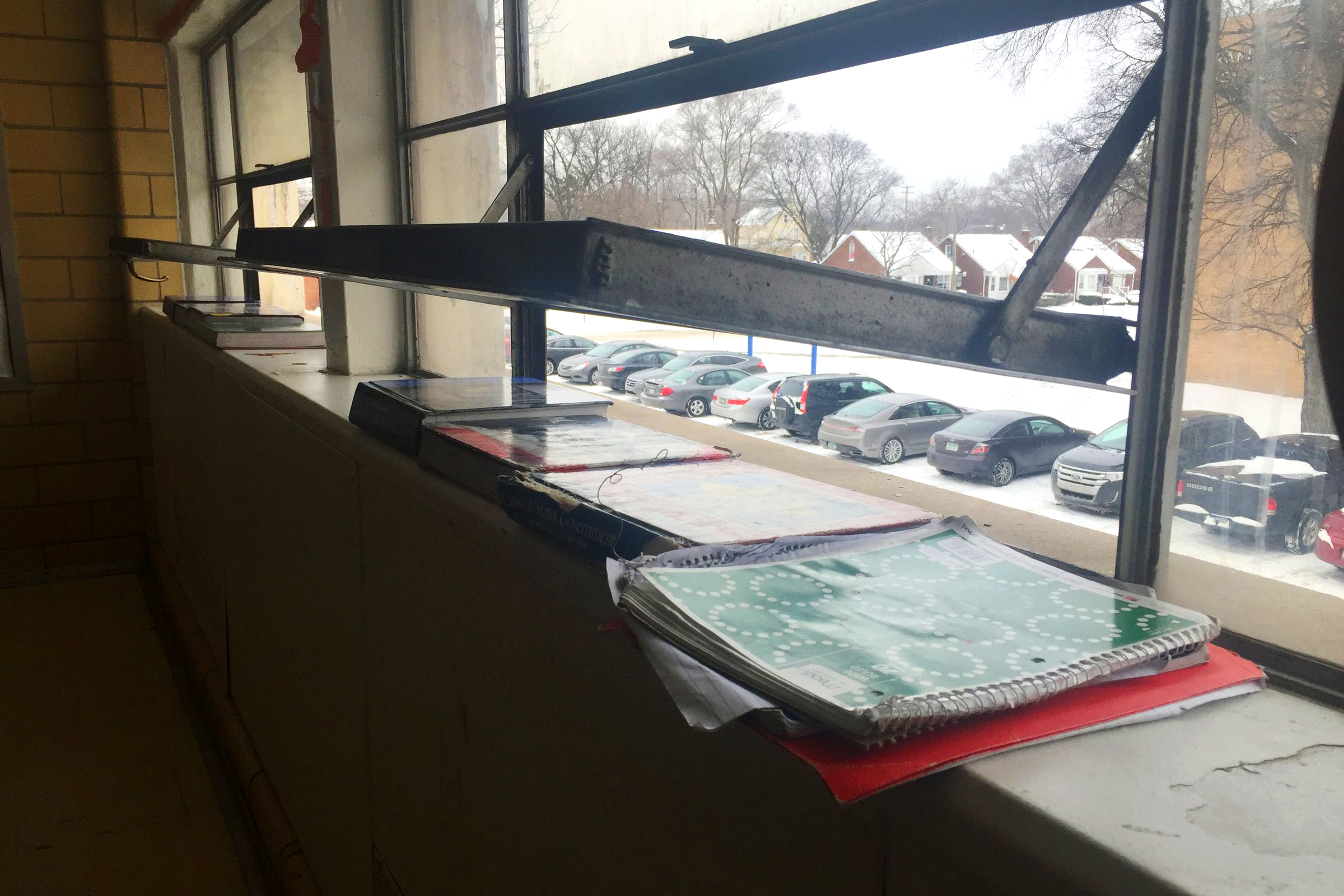

In January, Detroit teachers also sicked-out to protest what they said were horrific conditions in the schools, including vermin infestations, frigid temperatures and overcrowded classrooms. In the story below, Erin Einhorn talked to Detroit teachers about why they were staging the protest.

Thousands of people have fled the Detroit public schools, but Alise Anaya decides every day to do the opposite, commuting from the suburbs to teach in one city school and drop her children off at another.

It’s a surprising choice. Anaya grew up in Southwest Detroit, but many of the families she was raised alongside have left the city’s public schools in part because of conditions like those Anaya and hundreds of her colleagues have highlighted in a recent series of protests and sickouts — dead rodents, rotting floors and overcrowded classrooms.

The sickouts have shuttered dozens of schools on several days this month including on Jan. 20 – the day President Obama was in town – when 88 of the city’s 100 schools were closed. The teacher’s union took their complaints even further on Thursday, filing suit against the district to demand building repairs and the removal of the state-appointed emergency manager who runs the system.

The teacher’s frustrations reflect the alarming realities of a district struggling to survive after losing the bulk of its students. As Detroit’s population has plummeted and its schools have faced new competition from suburban and charter schools, the city’s public schools have gone from educating nearly 300,000 students in 1966 to just under 48,000 today. The district now carries an estimated $3.5 billion in debt.

And families are not the only ones leaving. Many of Detroit’s teachers have left, too, in search of better pay and cleaner, safer conditions in charter schools or the suburbs.

But Anaya, 32, is among those who’ve doubled down. Not only has she remained committed to the school system where she and her mother have both taught for years, she has chosen Detroit schools for her own kids, driving them in every morning from her home in suburban Allen Park.

Her son, Victor, 10 and daughter Analise, 8, attend the Academy of the Americas in Southwest Detroit, where classes are taught in both English and Spanish. Anaya teaches English as a Second Language at Clippert Academy, a middle school a few blocks away.

“My neighbors think I’m crazy,” she said of her decision to bypass a solid public school in Allen Park in favor of schools in a district that ranks dead last — or near the bottom — on most national measures. But Anaya said those statistics can obscure the caliber of teachers who remain committed.

“Because of all the cuts that have happened and so many teachers have left, the teachers that stay are really motivated. They really are staying out of the goodness of their hearts and they feel that this is where they need to be,” Anaya said. “Those are the kinds of people I want in front of my kids in the classroom.”

When teachers started calling in sick to protest deteriorating conditions in recent weeks, critics — including Emergency Manager Darnell Earley — accused them of harming children by depriving them of crucial learning time. The district has sought temporary restraining orders to block future sickouts. So far, judges have refused to grant the injunctions.

“Detroit Public Schools is a district that has been going through some very difficult financial challenges over the last number of years and we’ve worked very hard over the last year to get our internal house in order,” said Michelle Zdrodowski, a spokesperson for the district. “We’re getting resources into the classroom and school buildings. But while we do understand their frustrations, we don’t agree with their method of voicing those frustrations. Students need to be school every day and to take a day of instruction away is not necessarily appropriate in our estimation.”

Read More: Inside Detroit’s Plan to Woo Middle Class Parents

Teachers say the protests are not about harming children, but rather securing their future.

“This is very personal to me,” said Nina Chacker, 29, who teaches deaf and hard of hearing children at Detroit’s Schulze Academy and is determined to send her three-year-old son to Detroit public schools. “I’ve lived here my whole life. I own the house I grew up in. I don’t want to be doing anything other than teaching children in the public schools in Detroit.”

Chacker said she initially resisted the push from colleagues to stage a sickout. But when Schulze teachers decided twice this month to take that step, she was persuaded that they had no other choice. “We knew this was the course of action we needed to take,” Chacker said. “Nothing was happening and things were just getting worse and worse. We finally had to be a little more bold.”

For Anaya, calling in sick was a way to fight for her own children – and for the kids in her classroom. “I have to be an advocate for these children,” she said. “Without the dedication of the teachers, no one would even know about the things happening inside of DPS.”

Read More: Lessons from Detroit’s Fight to Survive

Like many DPS teachers and parents, Anaya recognizes the system can be exasperating. As in many of the city’s schools, hard-to-fill teacher vacancies have swelled some class sizes at Clippert into the high 40s. People who enter the basement classrooms at her children’s school are often assaulted by the smell of mold, she said.

It’s been enough that Anaya has been tempted to find another job. She was invited to interview at a school in affluent Ann Arbor a few years ago, but ultimately backed out. “I know there are safer and cleaner places that obviously will pay me more money but I can’t imagine myself somewhere else. This is where I belong,” she said.

Although she moved out of Southwest Detroit several years ago after a neighbor died from a heart attack when an ambulance was slow to arrive, she and her kids still spend most of their time in the old neighborhood. They go to school, attend church, do their shopping and participate in youth sports within blocks of Anaya’s childhood home.

The neighborhood has received an influx of new investment, especially in recent years as Detroit has emerged from bankruptcy to a flood of gushing attention. Suddenly, Southwest Detroit, a historically working class area long-populated by Mexican immigrants, has trendy restaurants and galleries.

Now, the city has to find a way to expand that urban renaissance to its schools–something Anaya says she and her fellow teachers are determined to make happen.

“We’re not going to rest until our kids get what they deserve,” Anaya said. “And I don’t think the rest of the world is going to rest either because now the world knows what’s going on.

Correction: The original version of this story understated the debt of the Detroit Public Schools. The total debt is estimated at $3.5 billion.

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com