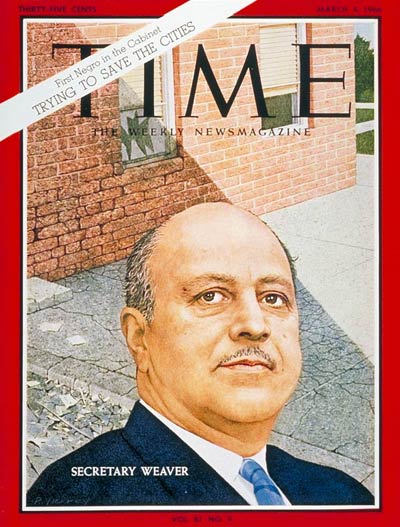

Exactly 50 years ago, on Jan. 13, 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Robert C. Weaver the secretary of the newly created Department of Housing and Urban Development, making him the first African-American member of the U.S. federal Cabinet.

The appointment made history and was the result of years of political infighting, so why did TIME’s cover story about the news declare that choosing Weaver was “unpredictably tapping the most predictable candidate for the job”?

Weaver certainly had the credentials. Born in 1907 and raised in a segregated Washington D.C., he went on to earn three degrees at Harvard, including a doctorate in economics—even though he thought of his brother as “the bright one.” After completing his education, Weaver joined FDR’s New Deal administration as a race-relations officer under Interior Secretary Harold Ickes. In the years that followed, he held a variety of positions relating to employment and housing discrimination, and was a prominent leader of what was popularly known as “The Black Cabinet,” the unofficial brain trust that TIME described as “an influential group of tough-minded young Negroes in F.D.R.’s Administration,” who “did much to bring full integration to Government offices.”

In 1960, Weaver was the board chairman of the NAACP when John F. Kennedy, then running for President, sought his advice on civil rights. Once elected, President Kennedy named Weaver the director of the Housing and Home Finance Agency, which was at the time the highest position in the U.S. government ever held by an African American.

But when Kennedy first proposed a new Department of Urban Affairs, in the spring of 1961, Congress resisted. When he later made it clear that Weaver would lead the agency, that resistance only grew. During the process Kennedy and Weaver knew that, as Weaver said, a large part of the population saw a vote “against this program as a vote against the concept of having a Negro in the Cabinet.” In order to get around the Congressional roadblock, Kennedy tried order the department’s creation through his reorganization powers, which could only be stopped by veto.

Despite Kennedy’s political maneuvering, “for the first time in 20 years, every member of the Senate was present to vote” and both the Senate and House rejected Kennedy’s new department in what TIME called “a humiliating Administration setback.”

It wasn’t till 1965, after Kennedy’s death, that President Johnson succeeded in creating a new department of Housing and Urban Development, coyly dancing around who would head it up. The intervening years—and perhaps Weaver’s work at HHFA and the progress of the civil-rights movement—had changed some minds in Congress. Democrats who had “charged earlier that Weaver would use his office primarily to promote racial integration in housing” said they were no longer concerned: “I thought he was going to be prejudiced,” said one Virginia Senator, “but I have seen no evidence of prejudice.” Weaver was approved quickly, becoming the first African American to ever be named a member of the President’s Cabinet.

As HUD secretary, Weaver championed the 1968 Fair Housing Act, which prohibited housing discrimination based on race, color, religion or national origin. “You cannot have physical renewal,” he was known to say, “without human renewal.”

Read more about Robert Weaver and the creation of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, here in the TIME Vault: Hope for the Heart

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com