It’s right there in the Constitution: the President of the United States “shall from time to time give to the Congress information of the state of the union, and recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.”

But when today’s presidents address the Congress and the nation to deliver the annual State of the Union address, they go one step beyond what’s strictly required. After all, the Constitution doesn’t say that Congress has to receive the State of the Union in the form of a speech.

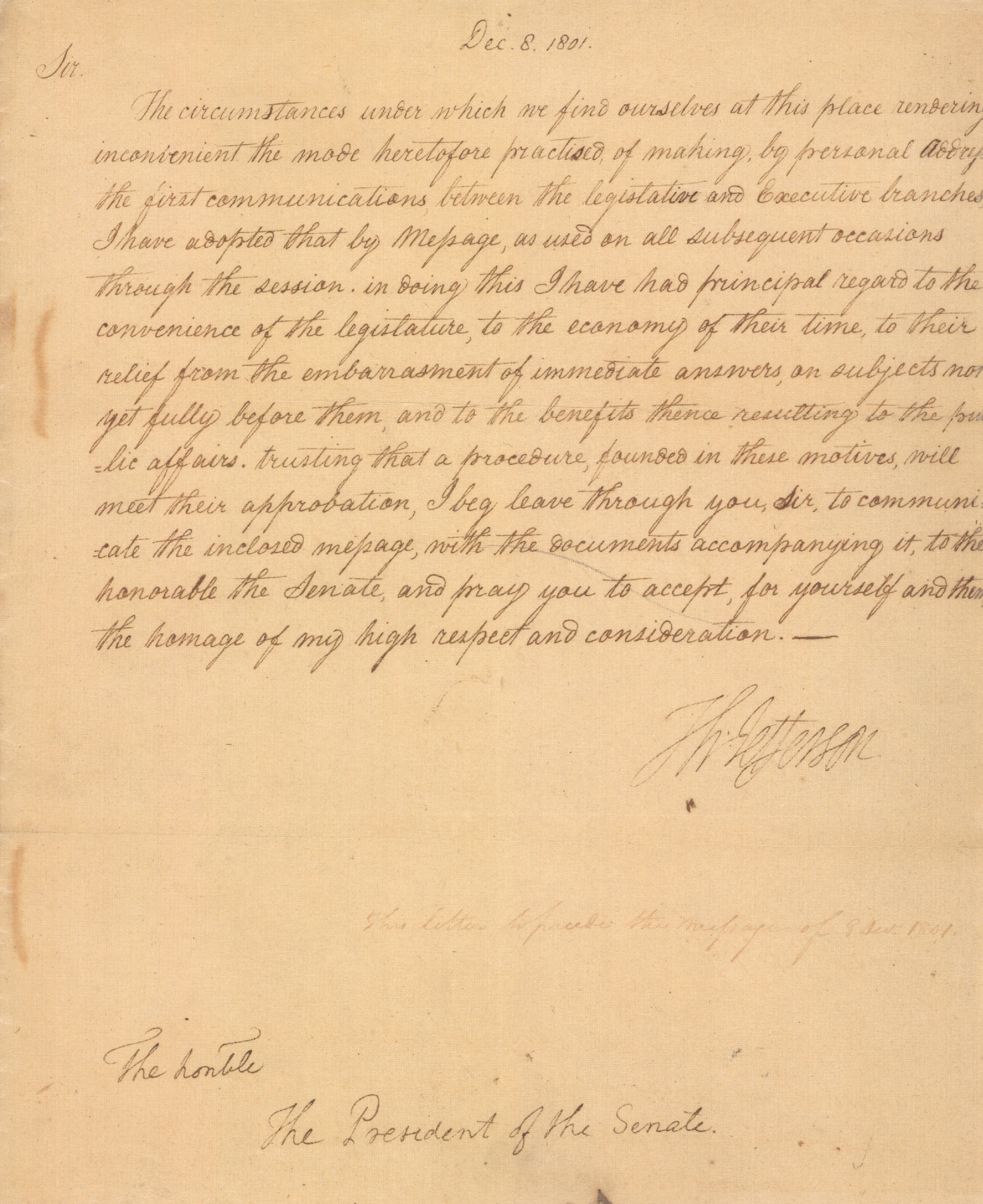

George Washington and John Adams interpreted the command as an instruction to appear in person; Washington delivered his first annual message to Congress on Jan. 8, 1790, though such a speech wouldn’t be widely known as a State of the Union address until many years later. But Thomas Jefferson started a new tradition by deciding to send his information in written form via messenger. In this 1801 letter, from the collections of the National Archives, he explains his reasons: it’s inconvenient to give a speech, it takes more time than reading and it robs legislators of the ability to think before responding.

Jefferson’s new tradition of delivering the State of the Union address in writing would endure for more than 100 years, until 1913, when Woodrow Wilson revived the tradition of giving the speech in person. Ever since, the written option became less common as radio and then television spread. These days, the spoken component of the State of the Union is a given. The last President to deliver only a written version was lame duck Jimmy Carter in 1981.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com