Tension has been building for weeks in a rural stretch of southeast Oregon over the cases of local ranchers Dwight and Steven Hammond, who were sentenced to additional time in prison in a dispute with the government over their use of public lands. But the battle, which has led to an armed militia occupying a building at a federal wildlife refuge, is far older, with roots in a decades-long fight between citizens and the federal government over who controls the nation’s vast stretches of open land.

Here’s a quick primer:

In the early 1970s, two factors converged to tip public opinion in favor of tighter land-use policy. The first was a boom in housing development that gobbled-up previously open space, a land rush that was particularly acute in the West. In 1972 alone, 3 million acres of open land were developed. At the same time, the burgeoning environmental movement spread awareness of the potentially irreversible harm being done to once-pristine wilderness.

In response, states and the federal government tried to rein in development by passing restrictions on land use. Oregon was one of the states that was particularly assertive about tightening its grip. Under President Nixon—who oversaw the founding of the EPA—the Senate passed the National Land Use Policy and Planning Assistance Act, which would have established a national coordinated plan for dealing with public land (though the bill failed to pass the House).

But not everyone was happy with the government’s increased control over valuable Western lands. Ranchers had long grazed cattle on federal land through permits that gave them grazing rights, which were easy to obtain and relatively cheap. But increased regulation of those permits and scrutiny of individual ranchers led to protests over what they perceived as government overreach. In 1977, the League for the Advancement of States’ Equal Rights was founded to combat what they felt was the undue influence of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and other federal authorities. The group was a force behind the movement that became known as the Sagebrush Rebellion, during which legislatures in western states with a high concentration of public land attempted to take back control from the feds. Nevada popularized the term in 1979 when the sate passed the “Sagebrush Rebellion Act,” declaring that the state controlled nearly 50 million acres of BLM land within its borders. “Led mostly by local government officials, state lawmakers and ranchers, the Sagebrush movement is attempting to wrest control of as much as 400 million acres of the land now owned by the Federal Government,” TIME explained in 1980. “Several states, including Utah, Arizona and Wyoming, have passed resolutions laying claim to their federal land, and Nevada is planning to sue the Department of Interior and the Bureau of Land Management to win the rights to the federal land within its boundaries.”

The Sagebrush cause was aided by the election of Ronald Reagan, who personally identified with the rebels. In addition to lending his soapbox to the cause, Reagan appointed James G. Watt as Secretary of the Interior. The Wyoming-born Watt believed that land-use policies were tilted in favor of environmentalists, and he also backed the larger conservative movement for a smaller federal government. Watt opened federal lands to development and drilling, prompting environmental groups to respond with lawsuits. By 1982, TIME called him “the century’s most significant” Interior Secretary, as the Reagan administration began to sell off huge parcels of federal land. (One irony: at the time, some ranchers and farmers actually found themselves on the side of federal regulation, hoping to prevent mining interests from snapping up the land. “For ranchers, profits and conservation go hand in hand,” TIME wrote in 1983. “Preservation of federal lands means continued access to vast grazing areas. The sell-off threatens this arrangement, since ranchers may not be able to afford to buy the acreage for which they now hold federal grazing permits.”)

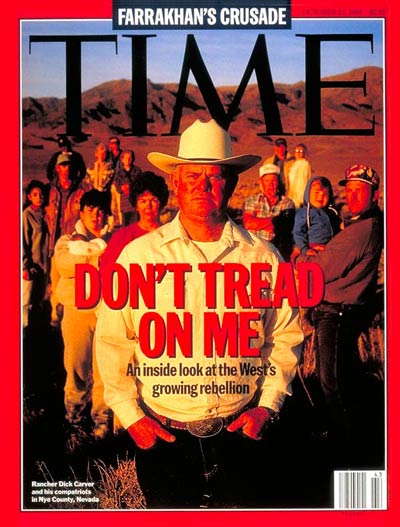

Although tempers cooled in the years following the Sagebrush Rebellion, the movement lit a fuse that continued to burn. In Nye County, Nev. in 1995, the Justice Department had to file a lawsuit to prevent the county from taking over the land. That year, TIME estimated that 75 counties had taken or were considering steps to take back federally-owned land in their states.

Speaking then about the feeling in some quarters, one Montana sheriff struck an ominously prescient note. “The paranoia is so deep,” Jay Printz, sheriff of Ravalli County, Montana, told TIME in 1995. “I just hope it doesn’t deteriorate into armed confrontations.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com