A prominent educator and patron of the arts, Henry Cole travelled in the elite, social circles of early Victorian England, and had the misfortune of having too many friends.

During the holiday season of 1843, those friends were causing Cole much anxiety.

The problem were their letters: An old custom in England, the Christmas and New Year’s letter had received a new impetus with the recent expansion of the British postal system and the introduction of the “Penny Post,” allowing the sender to send a letter or card anywhere in the country by affixing a penny stamp to the correspondence.

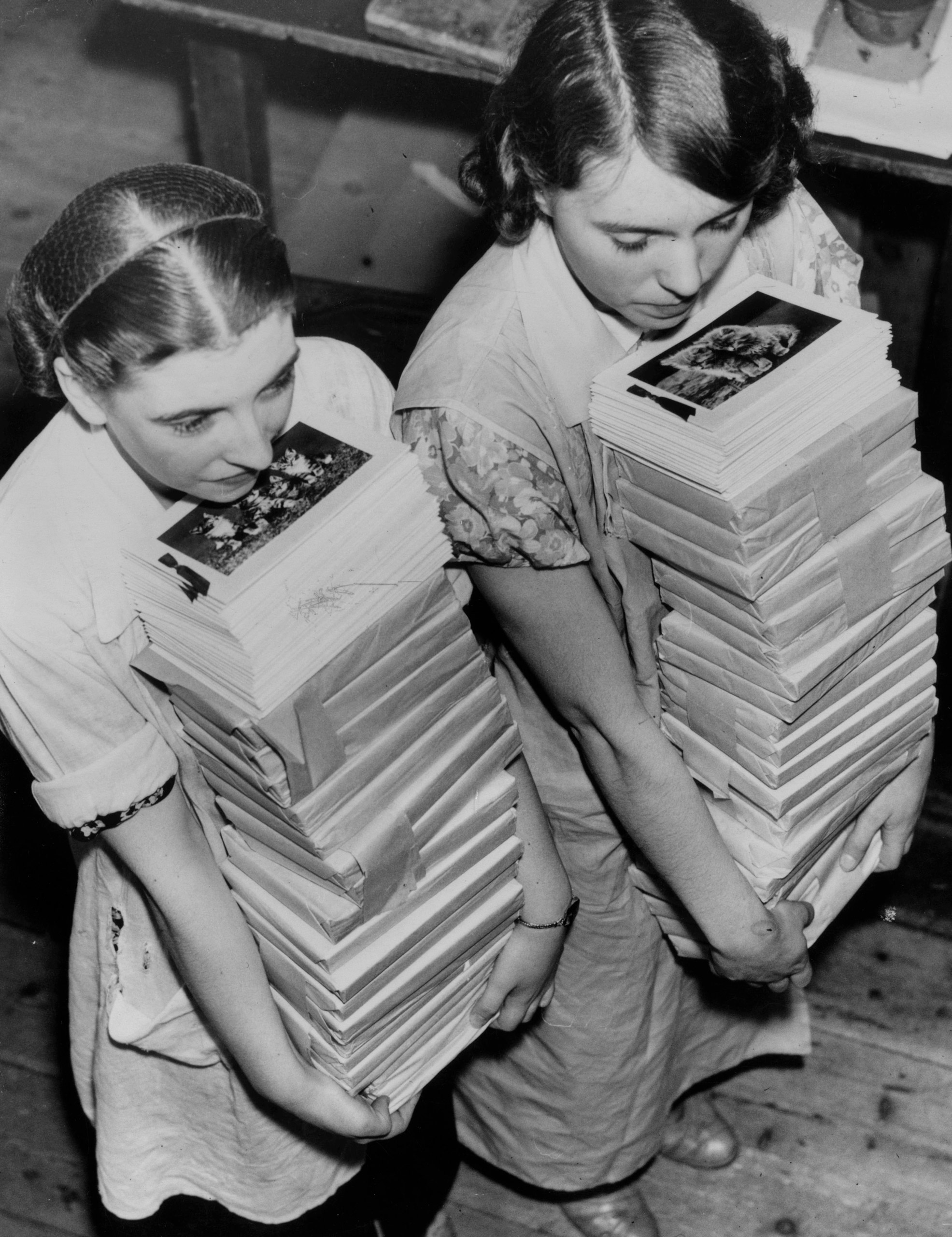

Now, everybody was sending letters. Sir Cole—best remembered today as the founder of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London—was an enthusiastic supporter of the new postal system, and he enjoyed being the 1840s equivalent of an A-Lister, but he was a busy man. As he watched the stacks of unanswered correspondence he fretted over what to do. “In Victorian England, it was considered impolite not to answer mail,” says Ace Collins, author of Stories Behind the Great Traditions of Christmas. “He had to figure out a way to respond to all of these people.”

Cole hit on an ingenious idea. He approached an artist friend, J.C. Horsley, and asked him to design an idea that Cole had sketched out in his mind. Cole then took Horsley’s illustration—a triptych showing a family at table celebrating the holiday flanked by images of people helping the poor—and had a thousand copies made by a London printer. The image was printed on a piece of stiff cardboard 5 1/8 x 3 1/4 inches in size. At the top of each was the salutation, “TO:_____” allowing Cole to personalize his responses, which included the generic greeting “A Merry Christmas and A Happy New Year To You.”

It was the first Christmas card.

Unlike many holiday traditions—can anyone really say who sent the first Christmas fruitcake?—we have a generally agreed upon name and date for the beginning of this one. But as with today’s brouhahas about Starbucks cups or “Happy Holidays” greetings, it was not without controversy. In their image of the family celebrating, Cole and Horsley had included several young children enjoying what appear to be glasses of wine along with their older siblings and parents. “At the time there was a big temperance movement in England,” Collins says. “So there were some that thought he was encouraging underage drinking.”

The criticism was not enough to blunt what some in Cole’s circle immediately recognized as a good way to save time. Within a few years, several other prominent Victorians had simply copied his and Horsley’s creation and were sending them out at Christmas.

While Cole and Horsley get the credit for the first, it took several decades for the Christmas card to really catch on, both in Great Britain and the United States. Once it did, it became an integral part of our holiday celebrations—even as the definition of “the holidays” became more expansive, and now includes not just Christmas and New Year’s, but Hanukkah, Kwanzaa and the Winter Solstice.

Louis Prang, a Prussian immigrant with a print shop near Boston, is credited with creating the first Christmas card originating in the United States in 1875. It was very different from Cole and Horsley’s of 30 years prior, in that it didn’t even contain a Christmas or holiday image. The card was a painting of a flower, and it read “Merry Christmas.” This more artistic, subtle approach would categorize this first generation of American Christmas cards. “They were vivid, beautiful reproductions,” says Collins. “There were very few nativity scenes or depictions of holiday celebrations. You were typically looking at animals, nature, scenes that could have taken place in October or February.”

Appreciation of the quality and the artistry of the cards grew in the late 1800s, spurred in part by competitions organized by card publishers, with cash prizes offered for the best designs. People soon collected Christmas cards like they would butterflies or coins, and the new crop each season were reviewed in newspapers, like books or films today.

In 1894, prominent British arts writer Gleeson White devoted an entire issue of his influential magazine, The Studio, to a study of Christmas cards. While he found the varied designs interesting, he was not impressed by the written sentiments. “It’s obvious that for the sake of their literature no collection would be worth making,” he sniffed. (White’s comments are included as part of an online exhibit of Victorian Christmas cards from Indiana University’s Lilly Library)

“In the manufacture of Victorian Christmas cards,” wrote George Buday in his 1968 book, The History of the Christmas Card, “we witness the emergence of a form of popular art, accommodated to the transitory conditions of society and its production methods.”

The modern Christmas card industry arguably began in 1915, when a Kansas City-based fledgling postcard printing company started by Joyce Hall, later to be joined by his brothers Rollie and William, published its first holiday card. The Hall Brothers company (which, a decade later, change its name to Hallmark), soon adapted a new format for the cards—4 inches wide, 6 inches high, folded once, and inserted in an envelope.

“They discovered that people didn’t have enough room to write everything they wanted to say on a post card,” says Steve Doyal, vice president of public affairs for Hallmark, “but they didn’t want to write a whole letter.”

In this new “book” format—which remains the industry standard—colorful Christmas cards with red-suited Santas and brilliant stars of Bethlehem, and cheerful, if soon clichéd, messages inside, became enormously popular in the 1930s-1950s. As hunger for cards grew, Hallmark and its competitors reached out for new ideas to sell them. Commissioning famous artists to design them was one way: Hence, the creation of cards by Salvador Dali, Grandma Moses and Norman Rockwell, who designed a series of Christmas cards for Hallmark (the Rockwell cards are still reprinted every few years). (The Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art has a fascinating collection of more personal Christmas cards sent by artists including Alexander Calder.)

The most popular Christmas card of all time, however, is a simple one. It’s an image of three cherubic angels, two of whom are bowed in prayer. The third peers out from the card with big, baby blue eyes, her halo slightly askew.

“God bless you, keep you and love you…at Christmastime and always,” reads the sentiment. First published in 1977, that card—still part of Hallmark’s collection—has sold 34 million copies.

The introduction, 53 years ago, of the first Christmas stamp by the U.S. Post Office perhaps speaks even more powerfully to the popularity of the Christmas card. It depicted a wreath, two candles and had the words “Christmas, 1962.” According to the Post Office, the department ordered the printing of 350 million of these 4-cent, green and white stamps. However, says Daniel Piazza, chief curator of philately for the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum, “they underestimated the demand and ended up having to do a special printing.”

But there was a problem.

“They didn’t have enough of the right size paper,” Piazza says. Hence, the first printing of the new Christmas stamps came in sheets of 100. The second printing was in sheets of 90. (Although they are not rare, Piazza adds, the second printing-sheets of these stamps are collectibles today).

Still, thanks to the round the clock efforts by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, a total of one billion copies of the 1962 Christmas stamp were printed and distributed by the end of the year.

Today, much of the innovation in Christmas cards is found in smaller, niche publishers whose work is found in gift shops and paper stores. “These smaller publishers are bringing in a lot of new ideas,” says Peter Doherty, executive director of the Greeting Card Association, a Washington, D.C.-based trade group representing the card publishers. “You have elaborate pop up cards, video cards, audio cards, cards segmented to various audiences.”

The sentiments, too, are different than the stock greetings of the past. “It’s not always the touchy-feely, ‘to you and yours on this festive, glorious occasion’ kind of prose,” says Doherty. “Those cards are still out there, but the newer publishers are writing in a language that is speaking to a younger generation.”

Henry Cole’s first card was a convenient way for him to speak to his many friends and associates without having to draft long, personalized responses to each. Yet, there are also accounts of Cole selling at least some of the cards for a shilling apiece at his art gallery in London, possibly for charity. Maybe Sir Cole was not only a pioneer of the Christmas card, but prescient in his recognition of another aspect of our celebration of Christmas.

It’s big business.

This article originally appeared on Smithsonianmag.com

More from Smithsonianmag.com:

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com