It’s more than an hour before the Denver Nuggets tip off against the Golden State Warriors, but Denver’s downtown arena is already filling up. Fans crowd around the Warriors’ basket, camera phones held high, as Stephen Curry floats shot after shot from the farthest reaches of the three-point line. They find the hoop with ease, guided as if by laser. Curry then steps near half-court, almost 40 feet from the basket, and starts again. Splash, splash, splash. “Look at it! I have not seen him miss one!” says Ty Hansen, a Nuggets fan whose allegiance to the home team seems to fade with every swish. “Another one! This is ridiculous. This is too much fun!”

These exultant scenes have played out in arenas across the nation over the past two months as Curry and the Warriors, who won the 2014–15 league championship, began the 2015–16 season with a romp through the NBA. Golden State got off to the hottest start in league history, setting an NBA record by winning its first 24 games. If you include last season’s final games, the streak of 28 is second only to the 33 won by the 1971–72 Los Angeles Lakers–a team considered among the best of all time. If they keep it up, the Warriors may claim another mark: the record for regular-season wins, 72, held by Michael Jordan’s 1996 Chicago Bulls. Along the way, Curry will chase a second straight MVP award, a back-to-back NBA title and an Olympic gold medal as a member of Team USA at the Rio Games.

And that’s just on the court. Sales of Curry jerseys are up 500% this season, according to online retailer Fanatics, topping LeBron James gear to become the best-selling getup in the NBA. Industry analysts credit Curry’s $130 sneaker with almost single-handedly doubling Under Armour’s basketball-footwear sales. President Obama invited him for a round of golf last summer on Martha’s Vineyard. And even Curry’s 3-year-old daughter, Riley, has become a star. After stealing the show at a postgame press conference during last season’s playoffs, the toddler was flooded with endorsement offers for diapers and baby shoes. Says Curry’s Warriors teammate Draymond Green: “Steph’s the face of the NBA.”

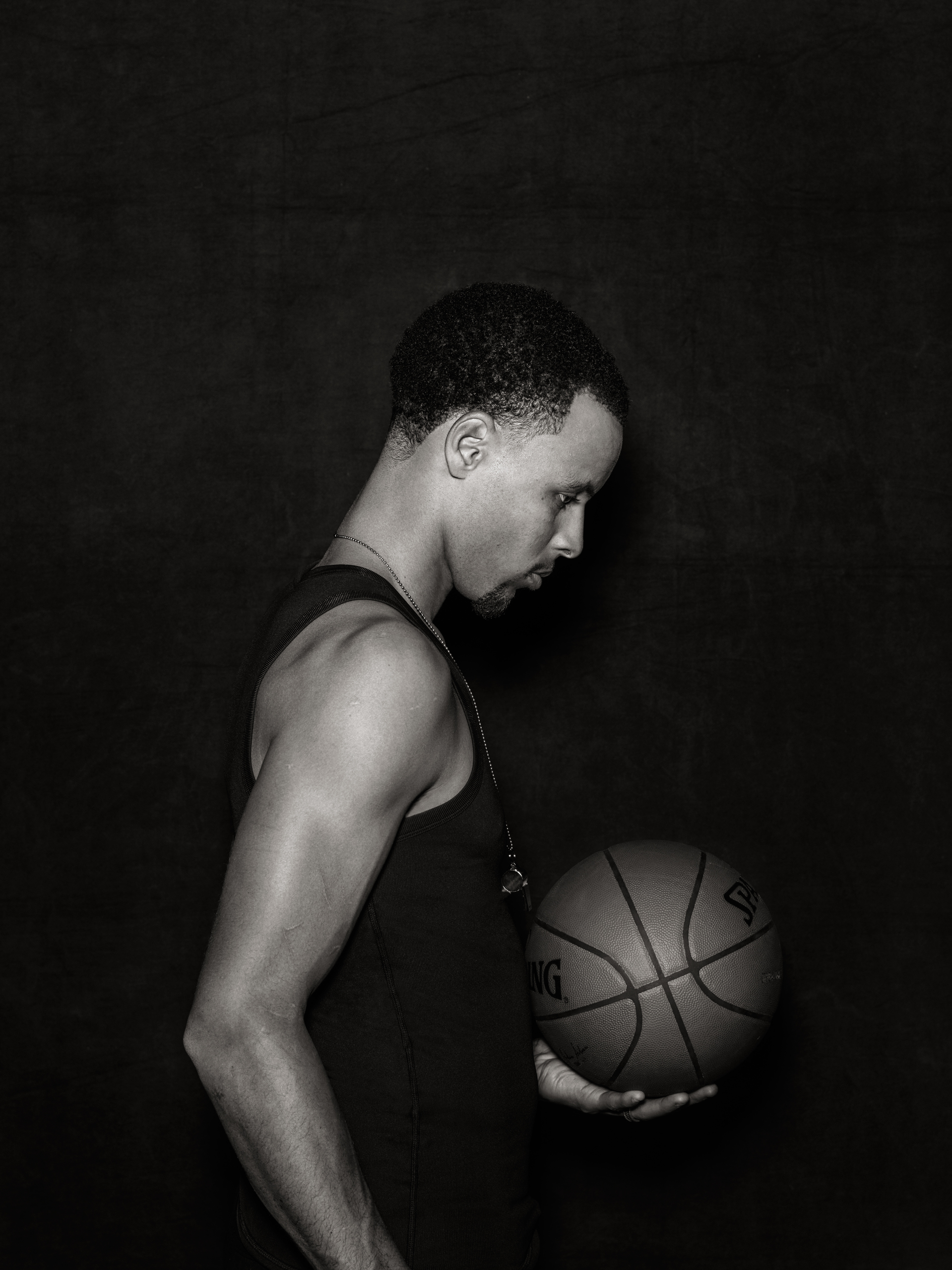

Heady stuff for a guy who wouldn’t look out of place at a YMCA pickup game. Curry is 6 ft. 3 in., with little discernible bulk. He’s 27, but a stab at facial hair–reddish-brown peach fuzz shaped into a goatee–barely makes him look drinking age. Next to most NBA players, Curry seems downright scrawny. He can shoot with a sniper’s aim, but rim-shaking dunks are few and far between.

This unconventional profile is partly why big-time colleges ignored him out of high school, why NBA opponents once disrespected him and why fans have come to love him. “Some of the stuff I do on the court is what most people think they can do,” Curry says over dinner at a Denver steak house in late November, the night before he dropped 19 points in three quarters on the Nuggets. “You see a guy like [Warriors teammate] Andre Iguodala take off on a fast break, he rises for a tomahawk dunk. I know I can’t do that. Most people can’t. Shooting the ball is a part of the game. Everyone can shoot their own way. Not everybody can make. But everybody can shoot.”

At the game the following day, Denver resident Blaine Schult is sitting courtside with his 8-year-old son–one of dozens of local kids sporting Curry jerseys. Asked why a family in the land of Nuggets fans is crazy for Curry, Schult responds as if he had been at dinner. “If you’re LeBron James, you’re an alien,” Schult says. “If you’re Steph Curry, you’re us.”

This isn’t true, of course. Curry is the son of a former NBA player, which gives him a genetic leg up unavailable to most of us. But that edge came with a few trade-offs. Curry went to high school in Charlotte, N.C., where his dad Dell, one of the NBA’s great long-range shooters, spent the bulk of his 16-year career. “There was a lot of pressure being Dell Curry’s son,” he says. Fans heckled him: “You’re not daddy! Daddy can’t help you!” Though he was named all-state, all of the major college basketball factories thought Curry was too frail. He wound up at Davidson, a liberal-arts college 20 miles north of Charlotte. Even there, Curry’s new teammates were skeptical of the scrawny freshman. “When I first saw him, he was this tiny kid who seemed lost,” says former Davidson forward Boris Meno. “It was like, Why did some parent leave their kid on campus?”

Curry soon quieted the doubters. A gym rat, he worked hard to improve on the shooting touch he’d inherited from his father. As a freshman, Curry averaged 21.5 points per game. The next season he drove his small college to within one shot of the 2008 Final Four, knocking off Georgetown and Wisconsin along the way. After leading the country in scoring his junior year, Curry declared for the NBA draft, where Golden State took him with the seventh overall pick. Curry showed flashes of greatness in his first three seasons in the Bay Area, but there were times when he still appeared overmatched. “I’d think to myself, ‘Boy, get off the court with these grown men,'” recalls his mother Sonya. He started to come into his own in 2013 and nearly made the All-Star team. Sonya remembers a parent at the Montessori school she runs trying to cheer her up about the rebuff. “Sorry about the snub,” the parent said. “But it’s not like he’s LeBron James or Kobe Bryant.”

Two years later, Curry’s Warriors beat James’ Cavaliers in the NBA Finals, bringing Golden State its first title in 40 years while extending Cleveland’s pro-sports title drought to 51 years. On Nov. 29, Bryant announced he would retire at the end of the season. James isn’t going anywhere, and he could well lead his team to another showdown with Curry in this season’s Finals. But it’s clear King James now shares top billing on the NBA’s marquee with the skinny kid no big-time college wanted. How did that happen?

Turns out Curry has perfect timing. Much like baseball before it, the NBA has been invaded by efficiency-obsessed number crunchers. After poring over the relationship between wins, losses, field-goal percentage, shots taken and dozens of other metrics, these NBA stat heads came up with a simple formula for success: play fast and shoot more. That is, taking lots of outside shots is a smarter strategy than methodically working the ball inside to big guys under the basket. As a result, teams today are taking and making more three-pointers per game than at any other time in NBA history. And the game is moving at its quickest pace in more than 20 seasons.

These trends are a perfect match for Curry’s skills. No one is better at creating space to take deep shots–critical when almost every defender is taller, stronger or faster–or at sending those shots into the net. This season Curry is making over five three-pointers a contest, more than the average for an entire NBA team 15 years ago. If he keeps it up, he’ll shatter his own record for three-point shots made in a single season, which he set a year ago. Curry has become the prototypical player of the current NBA.

“This game is evolutionary, and the days of pounding the ball five times to back into the basket are passé,” says Warriors executive board member Jerry West, the Hall of Fame player whose dribbling form inspired the NBA logo. “Young people will be mimicking Steph Curry for a very, very long time. He’s going to create a whole new brand of basketball player.”

This new brand of player zips in and around defenders, darting left, dashing right, stopping on a dime. He veers one way, then just as quickly comes to a pause, his body as calm as if he had never budged. Every movement is purposeful and unexpected, causing chaos among the defenders trying vainly to keep up. It reminds ballerina Misty Copeland a little of what she does onstage. “It’s like dancing,” says Copeland, the first African American to be a principal dancer at the American Ballet Theatre and Curry’s good friend. “If he didn’t have the rhythm, just this inner music you can hear, then I think people could predict his next move. And they can’t.”

Others see traces of marine life in Curry’s game. “I call him the tuna,” says Warriors player-development coach Bruce Fraser. “Tuna swim these channels. They’re torque-y. Like Steph, he’s torque-y. He’s like”–Fraser squiggles his hand to demonstrate–“then he’ll just burst. Tuna are hard to catch, but they’re not this huge thing either. But for their size, they’re mighty.” It’s a compliment but not one Fraser has ever mentioned to Curry. “What I am going to go,” Fraser says, “‘Hey, I call you the Tuna?'”

Curry works to keep up his aquatic edge. He won’t win many footraces against other NBA guards, but he can stop faster than all of them. This abrupt halt often sends defenders flying by, carried by their momentum, giving Curry the split second he needs to launch his deep shots. “Not being the fastest guy, that’s my biggest weapon,” he says. Curry hones this skill by dribbling with a band around his waist pulled by his trainer, Brandon Payne, as if he were a rock in a slingshot. Payne propels him at a higher speed than he could run on his own, allowing Curry to practice stopping quickly at that ramped-up pace.

Another favorite trick: overloading his brain. As part of his training regimen, Curry uses flashing lights to speed up his decisionmaking. While dribbling downcourt at full speed, Curry sees two sets of flashing lights on a pole, each color-coded to a specific task. Green, for example, can be a trigger to dribble between the legs, while blue means shoot a three. “It’s about letting your mind go free,” Curry says, shimmying his shoulders for effect, “while still having control of yourself.”

Some things, however, are innate. John Eric Goff, a professor of physics at Lynchburg College in Virginia, has calculated that Curry releases his ball 0.1 seconds faster than two other elite three-point shooters: Kyle Korver, the Atlanta Hawks marksman, and Steve Kerr, who ended his 15-year NBA career as its leader in three-point field-goal percentage and is now Curry’s head coach. Curry also launches the ball at an angle 1 to 3 degrees steeper than his peers. This gives his shot a higher arc and a more direct descent to the rim, exposing more of the hoop’s surface area and increasing Curry’s margin for error. “No one, not even Stephen Curry, violates the laws of physics,” says Goff. “Once he lets go of that ball, there’s nothing he can do to alter it. He has to optimize the trajectory under the laws of physics all of us have to obey. And he’s quite good at it.”

It may be no accident that Curry was born on March 14–Pi Day.

It has been more than a decade since Jordan retired for the third and final time, and the NBA has finally learned how to live without him. Dynamic stars like Curry, James, Kevin Durant and Chris Paul are among the best players and most marketable names in league history. Aside from James’ fumbled made-for-TV announcement to bolt Cleveland for Miami in 2010, they have all avoided the public missteps that have felled other athletic icons (see Woods, Tiger; Armstrong, Lance; and Rodriguez, Alex). In ads, their smiling faces tout international blue-chip companies such as Apple, Coca-Cola, Nike and Unilever.

The popularity of today’s NBA players has helped make teams more valuable than ever. In 2014, former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer bought the Los Angeles Clippers from disgraced owner Donald Sterling for an NBA-record $2 billion. But even franchises without Hollywood glitz are fetching hefty sums. The Atlanta Hawks, for example, went for $730 million in 2015, 124% higher than the average NBA team valuation a decade ago.

Much of this is because more people are tuning in to watch on TV. With recognizable stars and a fast-paced, high-scoring game, the NBA has ratings that have more than recovered from their post-Jordan slump. Last season’s Curry-vs.-James Finals matchup averaged almost 20 million viewers, making it the most watched championship series since Jordan’s last title run in 1998. Now media companies are writing record checks for the rights to televise the NBA. In 2014, the league announced a nine-year, $24 billion deal with ESPN and Turner Sports, a 180% increase over the previous agreement.

This boom time, however, is fragile. The collective-bargaining agreement between the league and the players’ union could expire after the 2016–17 season if either side opts out by December 2016. In 2011, a contract fight led to a lockout that shortened the season and cost players and owners an estimated $400 million each. To end that dispute, the players agreed to cut their share of overall basketball income from 57% to about 50%–a giveback that has left many players sore. With that memory fresh and the NBA’s fortunes rising, the players union is headed into the upcoming negotiations loaded for bear.

Curry, who sits on the union’s executive committee, is among the NBA stars who will use their clout at the bargaining table. “We’re much more organized than we’ve ever been,” he says. “Much more unified.” The players hired Michele Roberts, a prominent Washington trial attorney, to lead the negotiation. NBA commissioner Adam Silver, who in his second full season on the job has more goodwill among players and fans than his predecessor, won’t hand over the store. Silver has said that despite the league’s rising tide, a “significant number” of teams are still losing money.

In a way, Curry’s ascension could help precipitate a lockout. The more popular he and other players become, the harder the line they’ll take in negotiations and the better the odds that we’ll see another work stoppage. “You just look at the value of teams going up on a year-to-year basis, and you follow that trend, the players should be compensated accordingly,” Curry says. “That’s the simple message. We’ll fight for it.”

Given that Curry’s a bargain, at least by NBA MVP standards, he’s motivated to recoup his value. In October 2012, Curry signed a four-year, $44 million contract extension. An ankle injury had caused him to miss most of the previous season, so at the time, the deal was a good insurance policy. Now that contract is a steal for the Warriors. James, for example, is making $23 million this season–almost $12 million more than Curry. One of best players on the planet is the fifth highest paid player on his own team.

Curry knows he makes a great living, especially when factoring in his endorsement income. He and his wife Ayesha recently bought a $3.2 million house in Walnut Creek, Calif., an affluent suburb 16 miles east of his team’s arena in Oakland. Spending time with Curry, however, is a reminder of why his rep as “one of us” has stuck despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. He’s gracious over dinner, offering to share a shrimp cocktail, and quick with a joke. When Bob Fitzgerald, the Warriors’ play-by-play announcer, stops by the table, Curry launches into an impression of Ron Burgundy, Will Ferrell’s pompous newscaster from Anchorman. Another diner can’t resist a compliment as he walks by: “Steph Curry, you’re badass.” Curry laughs and turns to me right away. “You’ve got to put that in there,” he says.

Not all of this attention has to do with Curry’s ability to shoot a basketball. His daughter Riley has been quite good for the family brand too. Her rise from anonymous kid to viral star began last spring, when Curry brought her onto the press-conference dais after a Warriors playoff win. Curry had scored 34 points, but his young daughter’s antics were the center of attention. GIFs and web listicles like “30 of the Absolute Cutest Riley Curry Moments” soon followed, as did offers for Riley-branded kid gear. The family turned them down. “Too early,” Curry says. (New daughter Ryan, born this past summer, hasn’t attracted the same attention–yet.) “I do worry sometimes that when she gets to the age where she can process what’s going on, how she’ll handle it. Hopefully we have the foundation set: You’re a little different, your dad plays in the NBA. But that shouldn’t change who you are. I like our chances of being able to instill that in her.”

Perspective. It’s what Dell and Sonya worked to instill in Curry and his brother Seth, an NBA player with the Sacramento Kings, and their sister Sydel, a college student. And it’s what he worries about holding on to as his star rises into the stratosphere. “I’m learning you have to be proactive in that regard,” he says. “I don’t want to have a pessimistic attitude. But things are really great right now. We’re winning, there are so many life additions at home. It all comes at once. Eventually basketball will end. I have a lot of life to live after that. So I guess the only worry is not to just be defined as a basketball player.”

Asked if he sees similarities in his game to the greats of NBA history, Curry brings up Bob Cousy. The answer draws a chuckle from teammate Green, who darts around the Warriors locker room mimicking Cousy’s outdated dribbling style. Others aim higher. “He’s this generation’s Jordan,” Milwaukee Bucks coach Jason Kidd said before his team played Curry in December. “We all wanted to be like Mike, and children today will grow up seeing Steph.”

Like Mike, who never forgot the high school coach who cut him, Curry is driven by slights. He insists they don’t motivate him, but he brings up three from the off-season alone without prompting: Houston Rockets guard James Harden’s winning the players’ vote for MVP (the media votes for the official award), trash talk from a Rockets player about Curry’s defense in the playoffs and remarks from Clippers coach Doc Rivers that the Warriors avoided the toughest teams on their path to the championship.

Curry has these in mind as he lists his goals for 2016. He wants to win another championship and a gold medal in Rio and be a contender for the MVP (he was well on his way even before New Year’s). And he wants to have even more fun. “I smile, I laugh, I dance,” Curry says. “All those little ways that show that when I’m out there on the floor, you feel at home. You feel like this is where you’re supposed to be.”

Oh, and there’s one more thing we can look forward to from Curry in 2016. “You should expect me to keep getting better,” he says.

Scary. Stephen Curry thinks he’s just warming up.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Sean Gregory at sean.gregory@time.com