Chinese bureaucracy excels at record-keeping, and the ruling Chinese Communist Party’s official atheism isn’t preventing the latest effort in meticulous documentation. Earlier this month, the Chinese government announced that Beijing would be compiling a database of the nearly 360 “living Buddhas” — holy men considered reincarnations of Tibetan Buddhist luminaries — who are resident in China.

The State Administration for Religious Affairs, which has charged itself with compiling the living-Buddha database, did not respond to written questions from TIME. But the database announcement follows the issuing in September of a government white paper reiterating that Beijing “has undeniable endorsement right on the reincarnation system” of living Buddhas. A Chinese state media report said the spiritual cataloging, which will be available online, is designed to prevent the rise of unscrupulous pseudo living Buddhas who lure followers without proper religious credentials. Concern has grown because Tibetan Buddhism has gained a growing following among members of China’s Han majority, who are drawn by the sense of religious purity emanating from the Tibetan high plateau. (Locals, meanwhile, complain that an aggressive police presence in Tibet means they cannot access some of their holiest sites as freely as Han tourists can.)

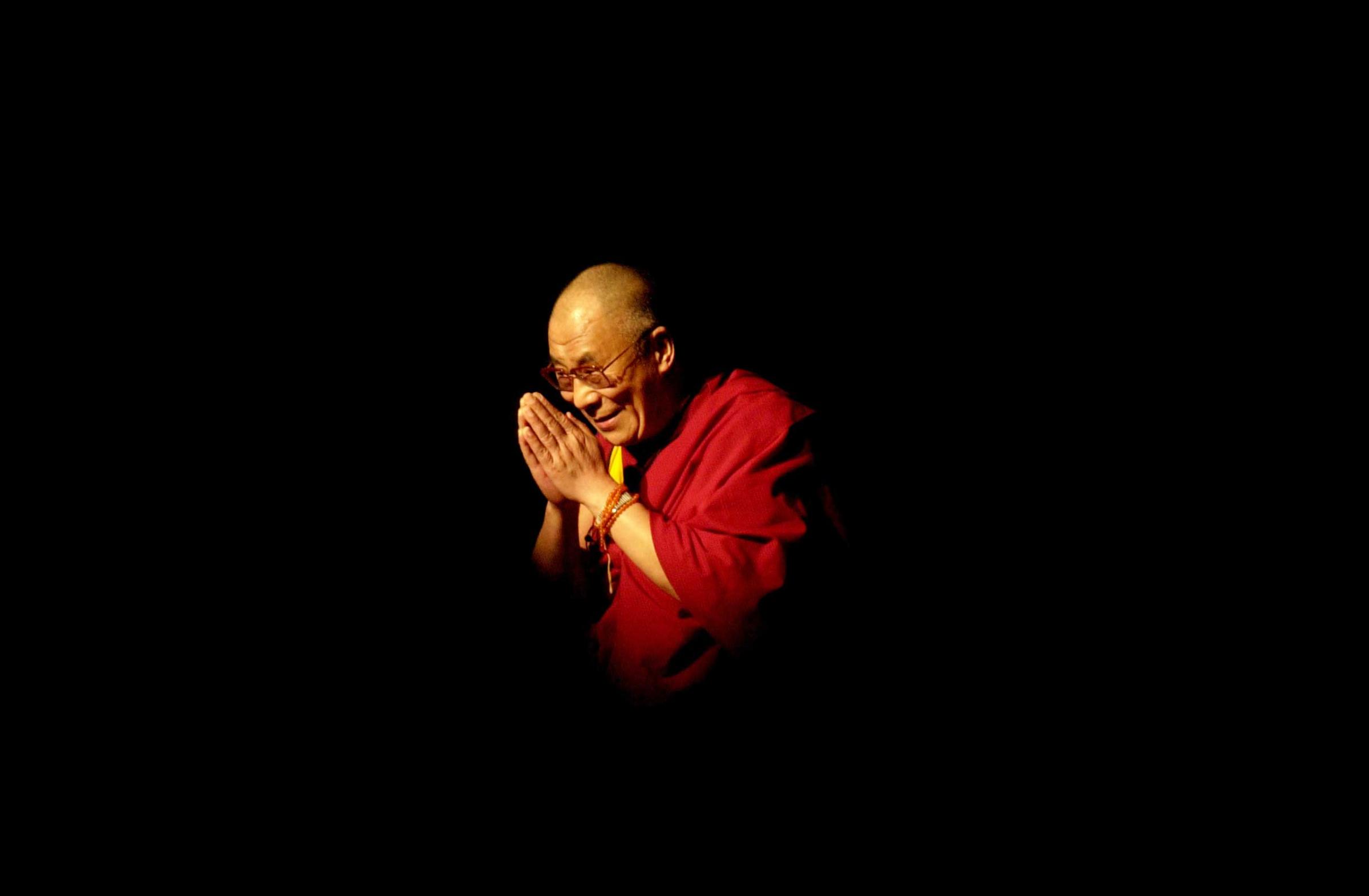

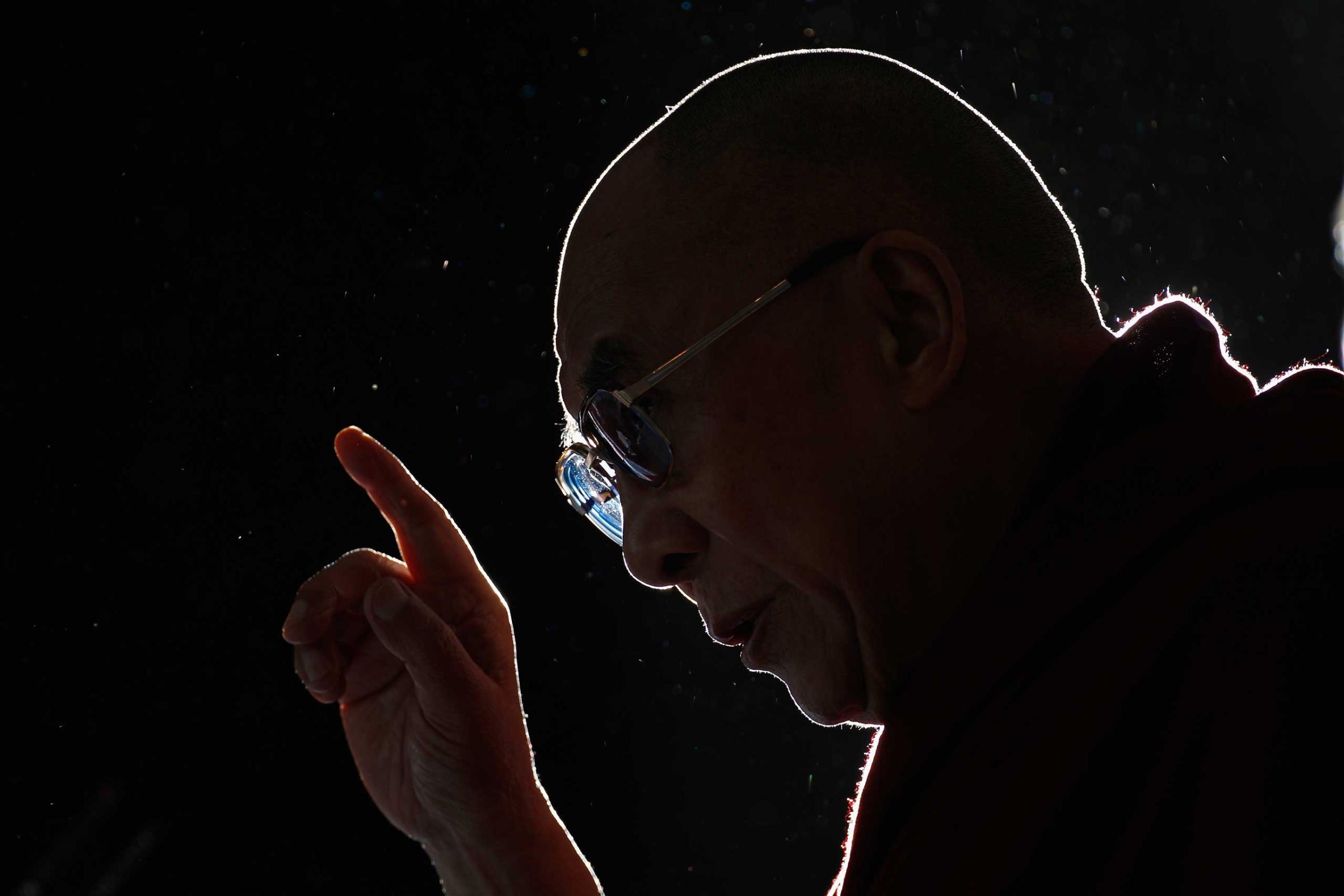

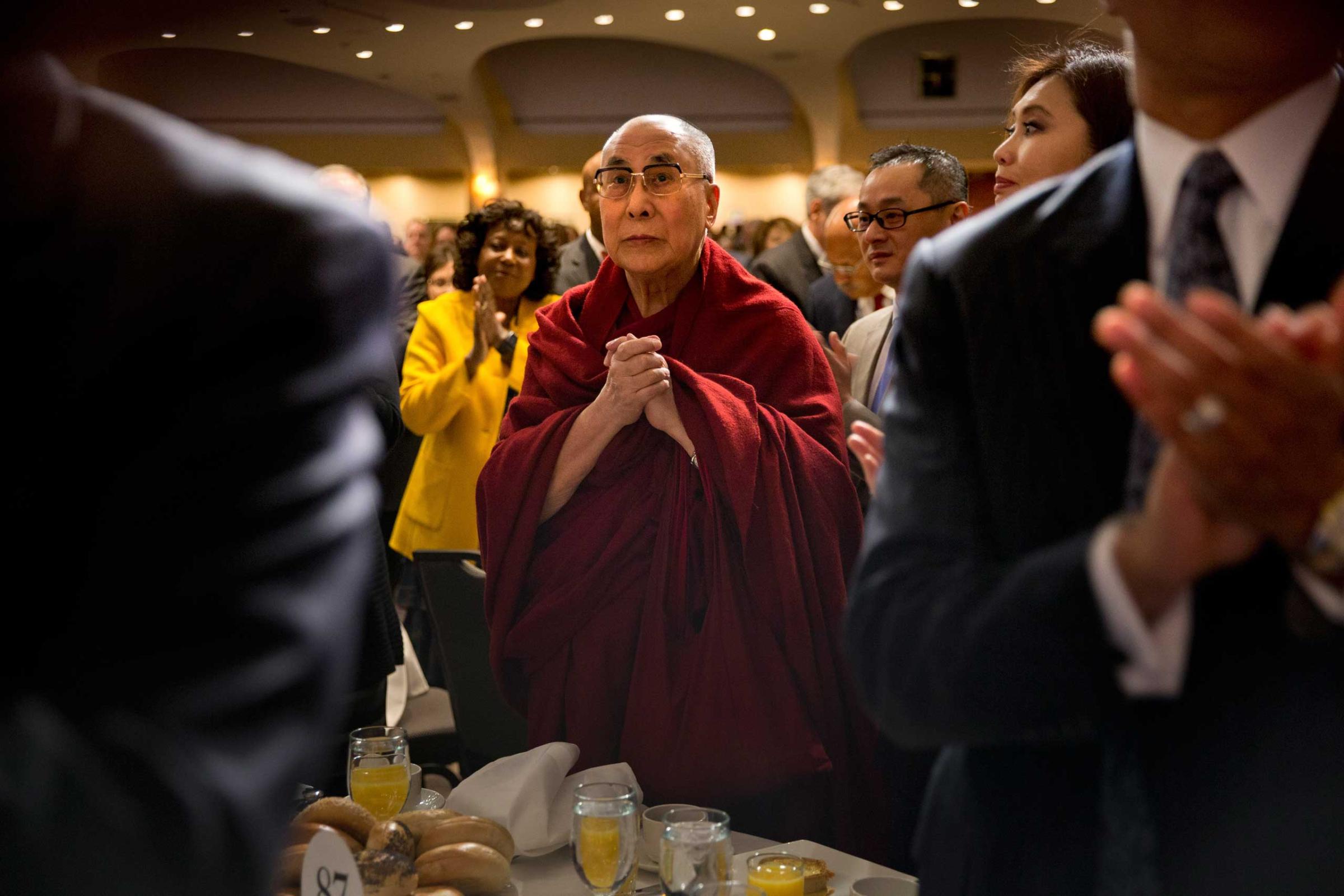

The Chinese government’s self-declared right to choose living Buddhas extends to the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism. The current Dalai Lama, considered the 14th reincarnation of a 15th century abbot, has lived in exile since a failed uprising against Chinese rule in 1959. Although the now 80-year-old monk has consistently called for meaningful autonomy for Tibet, as opposed to outright independence, Beijing considers the Dalai Lama a dangerous separatist and accuses him of orchestrating deadly 2008 protests across the Tibetan plateau, as well as the more than 130 self-immolations by Tibetans over the past few years — charges he rejects.

Traditionally, the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama is chosen by a coterie of high lamas, as senior Tibetan Buddhist monks are known. But the Communist Party now considers reincarnation one of its official duties. “This living-Buddha database and the whole policy toward reincarnation is clearly a preemptive move by the government to control what happens after this Dalai Lama,” says Nicholas Bequelin, regional director for East Asia at Amnesty International, who has tracked Tibetan topics for years. “They want to get ahead of the issue and prepare the ground for when the Dalai Lama dies.”

Meanwhile, the Tibetan spiritual leader has suggested that his replacement will not come from a Tibet where religious repression and cultural control have endured for more than half a century. “If the present situation regarding Tibet remains the same, I will be [reincarnated] outside Tibet away from the control of the Chinese authorities,” the Dalai Lama is quoted as saying on his website. “This is logical.” The Nobel Peace Prize laureate has also speculated that the long line of Dalai Lamas could end with him. “Whether the institution of the Dalai Lama remains or not depends entirely on the wishes of the Tibetan people,” he says on his website. “It is for them to decide.”

On Dec. 10, Lobsang Sangay — the Tibetan Prime Minister in exile, who has taken over some political responsibilities from the Dalai Lama — released a statement coinciding with World Human Rights Day and the 26th anniversary of the Dalai Lama being chosen to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. “Neither the muscle nor money of the Chinese government,” he wrote, “will change the belief of the Tibetan people in His Holiness the Dalai Lama to appoint the next Dalai Lama.”

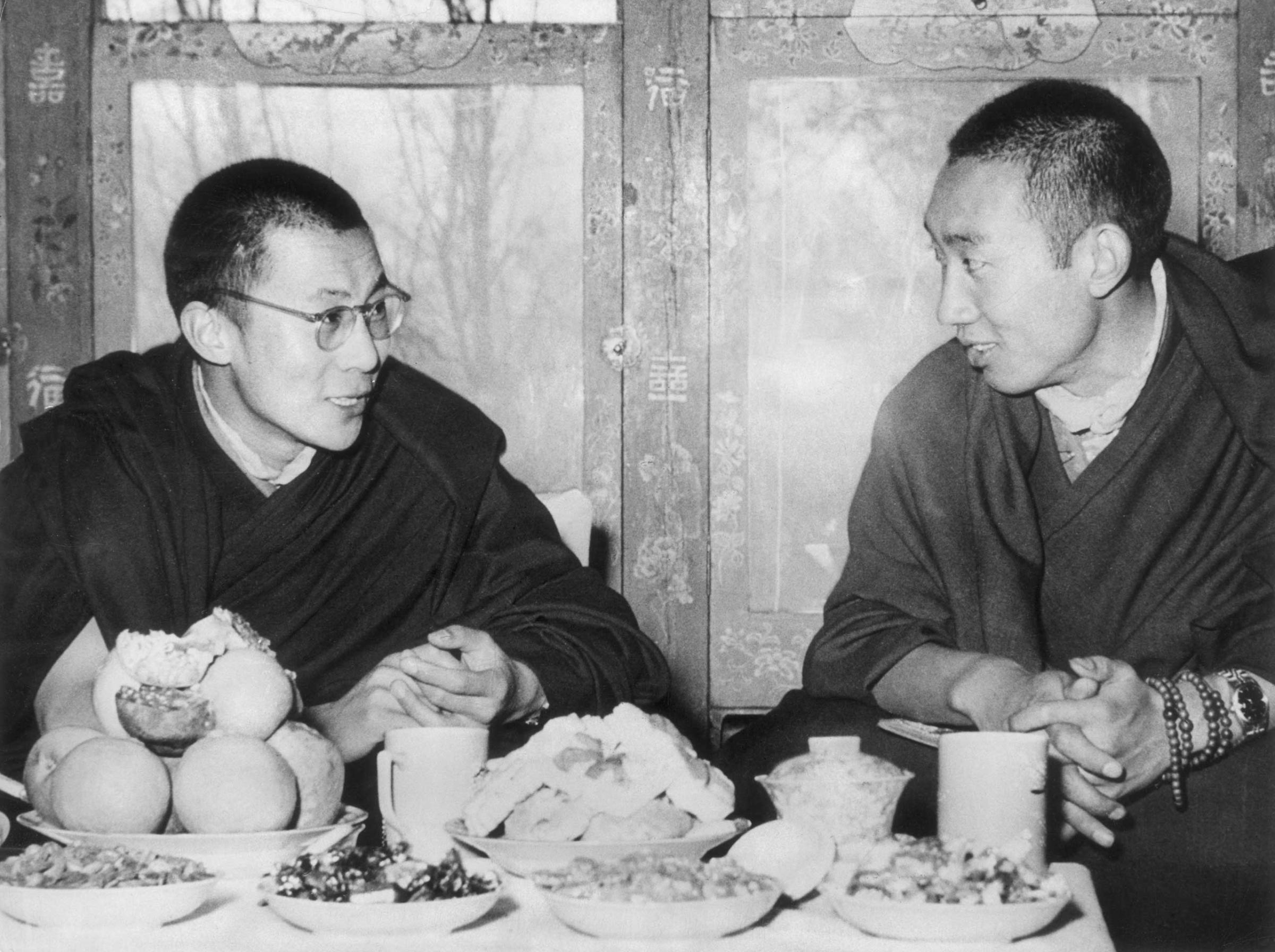

In 1995, the Dalai Lama designated a 6-year-old Tibetan boy as the 11th reincarnation of the Panchen Lama, the second holiest figure in the Tibetan-Buddhist cosmology. But shortly afterwards, Chinese authorities picked their own boy as Panchen Lama. The Dalai Lama’s choice, Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, has not been seen in public for more than two decades. A Chinese official was quoted in official media in September saying that the now grown boy is “living normally and growing healthily [and] does not want to be disturbed by anyone.” This month, the government-selected Panchen Lama celebrated the 20th anniversary of his enthronement. During an official ceremony, the 25-year-old, who is a vice president of the Buddhist Association of China, thanked the Chinese government for its “help and care,” according to Xinhua, China’s state news agency.

While Beijing’s Panchen Lama has been glorified in Chinese state media for his efforts in “incorporating Tibetan Buddhism into socialist society,” the Dalai Lama continues to be vilified in official circles. In ethnically Tibetan areas outside of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), such as in Yunnan or Gansu provinces, images of the Dalai Lama can be openly displayed, along with photographs of other high-ranking monks who have escaped into exile. But in the TAR proper, government oversight is harsher. Simply possessing the exiled leader’s image can earn monks jail sentences. Clerics complain that they are forced to attend patriotic-education classes in their monasteries and denounce their spiritual guru. “We must say their bad words [toward the Dalai Lama] but our hearts are full of love for His Holiness,” says one Tibetan monk from Labrang monastery in Gansu. “They cannot kill our love.”

Beijing counters that it has raised living standards dramatically in Tibetan areas, which are among China’s poorest. For instance, the central government spent $1.25 billion to educate Tibetan children in boarding schools, according to a state media report this month. Yet critics consider plucking young Tibetan nomads from their families as little more than crude Sinification by the Chinese state. There’s an economic imperative to the trend too. Tibetans who want to secure jobs with the state-owned companies flooding Tibet to mine its plentiful natural resources know they must master Mandarin, China’s national language, over any Tibetic language. More change is coming to the high plateau: next year, Lhasa, the regional capital, will welcome its first KFC outlet.

See the Dalai Lama's Life in Pictures

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com