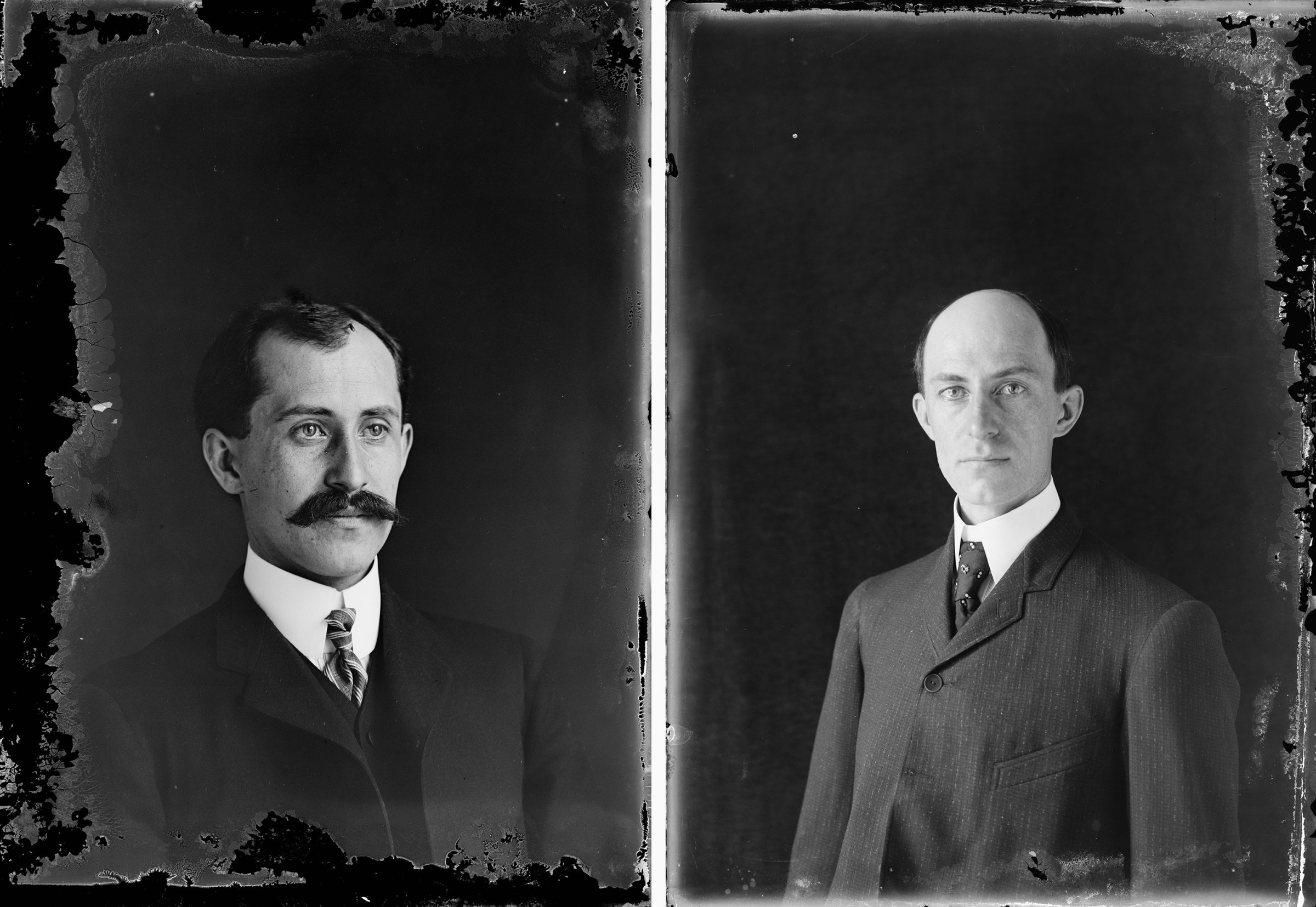

On this date in 1903, brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright made what many consider the world’s first successful heavier-than-air flight. The flight catapulted the brothers and their machine, the Wright Flyer, into history books. It also propelled them, over the decade to come, into courtrooms throughout Europe and North America.

In the courts, the Wright brothers waged a prolonged, embarrassing and largely unsuccessful battle against other early aviators over who owned the aeronautical principles that made flight possible. Citing a 1906 patent for their flying machine, the Wrights claimed these principles as their own and charged their competitors with intellectual property theft. Fighting back in court, the Wrights’ competitors claimed the theory behind the machines as the common property of humanity and argued that the Wrights’ patent pertained only to the mechanics of their airplane itself.

In waging this battle, the Wrights proved themselves more than pioneers in aviation. They also proved themselves pioneers of what’s sometimes known as patent trolling: the controversial modern practice of suing competitors for infringements that fall beyond the scope of one’s patent. Their legacy, therefore, is one of litigiousness and obstruction, as well as brilliance and innovation. Advancing aeronautics by leaps and bounds in the first years of the 20th century, Orville and Wilbur Wright squandered their talents and energies – and those of their most gifted rivals – in a period of legal wrangling between 1909 and 1917. American aviation would suffer immeasurably as a result, and the Wrights would establish dangerous precedents for subsequent generations of would-be patent trolls.

The Wright Brothers’ patent claim worked in much the same way that modern patent trolling does. Consider, for example, an oft-cited example of patent trouble from the last decade: Personal Audio. That company held a 2001 patent for “[a]n audio program and message distribution system in which a host system organizes and transmits program segments to client subscriber locations,” which it had taken out in connection with a proposed (but unfinished) MP3 player. Until their infringement lawsuits were invalidated in April 2015, the company used that patent to argue that they had invented the idea of podcasting, and that podcasters were therefore stealing their intellectual property. Though separated by a century, the contours of Personal Audio’s lawsuits and those filed by the Wright brothers are basically identical.

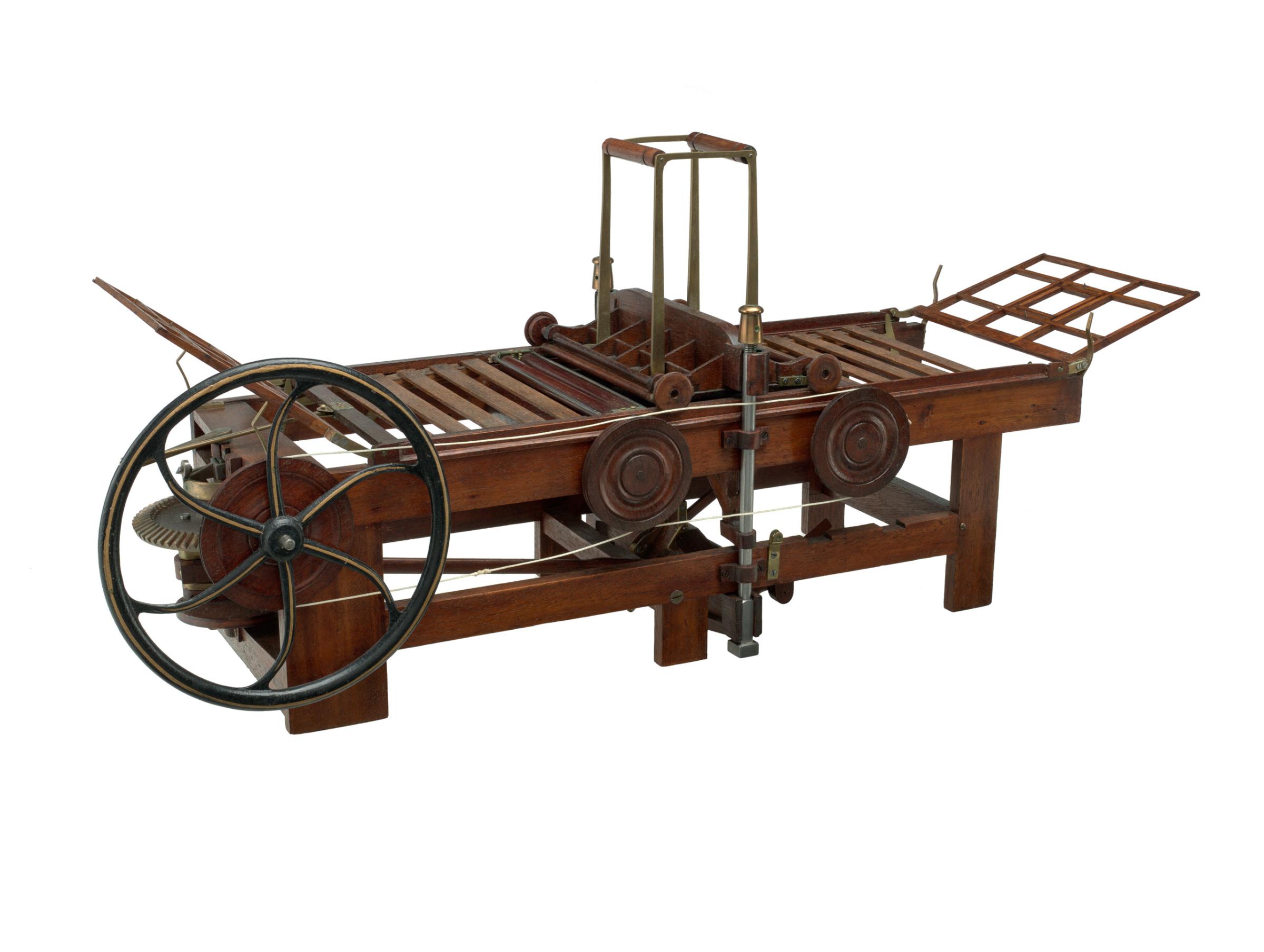

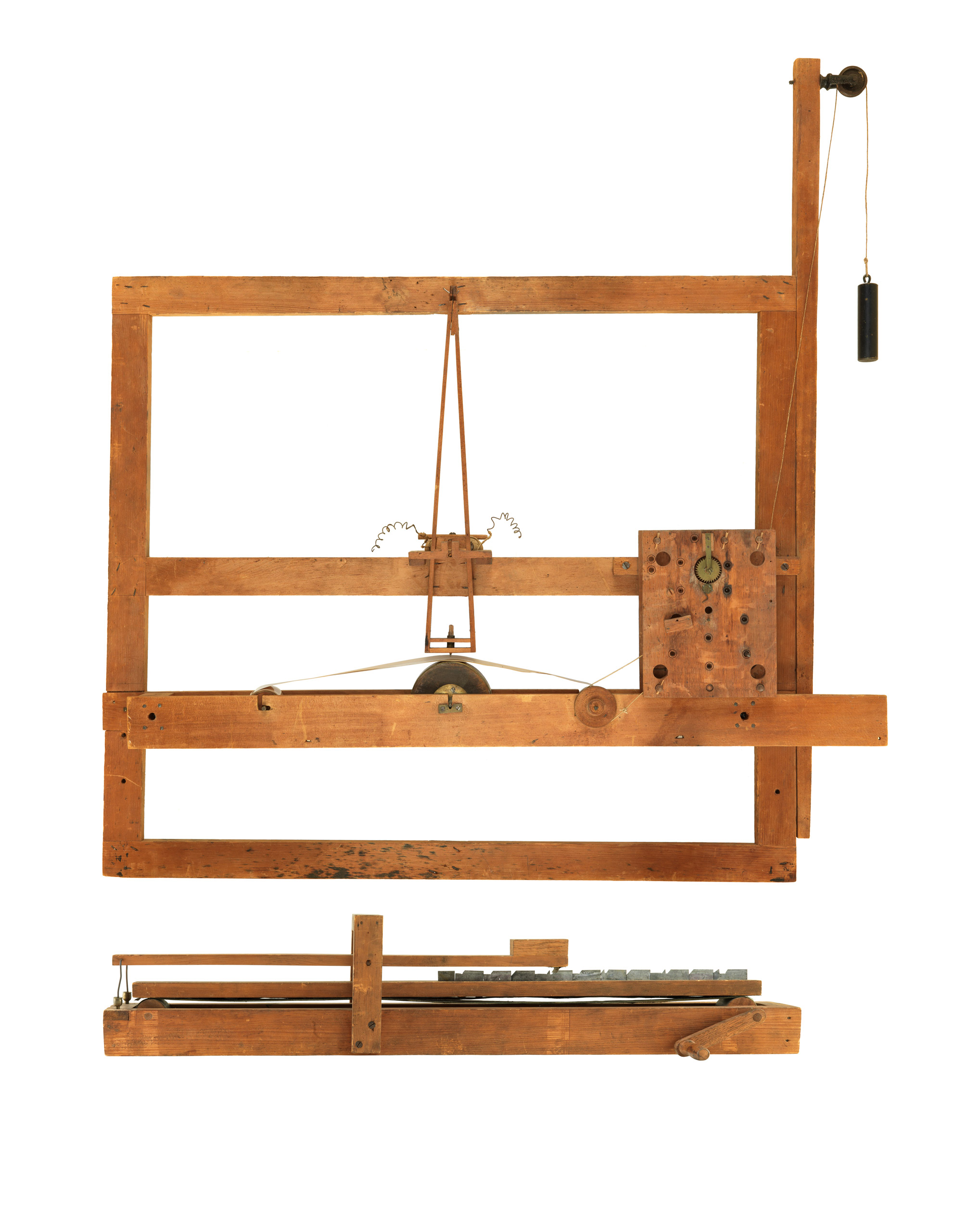

To understand the Wright Brothers’ lawsuits, we must first consider the content of their patent. Awarded three years after their first flight, the Wrights’ patent for a “flying machine” focused on the brothers’ most groundbreaking contribution to the study of aeronautics: their innovative mechanism for controlling an aircraft in flight.

In the Wrights’ design – and in nearly all subsequent aircraft – control was achieved through changes in what the brothers called the “lateral margins” of the airplane’s wings. In practice, this meant moving the rear outer tips of the wings in opposite directions, which the Wrights achieved by using wires to twist – or “warp” – the wood-and-fabric wings of the Flyer. As an example of what this looked like in practice, imagine twisting the sides of an open-ended spaghetti box in opposite directions.

Wing warping was the key innovation that made manned, powered flight a meaningful reality. While other early aircraft were capable of generating lift, all save the Wright Flyer were radically unstable and unspeakably dangerous. Orville and Wilbur, therefore, were rightly proud of their insight and deserved any and all intellectual property protections afforded by the law.

The Wrights, however, wished to patent not only their wing-warping mechanism but any future device for adjusting the “lateral margins” of an aircraft’s wings – and, in so doing, laid legal claim to the principle of aeronautic control they had discovered. If the patent were interpreted in the way they hoped, it would give them monopolistic control over the aircraft market for years to come.

Fortunately for the subsequent history of aviation, many of the Wrights’ earliest competitors were willing to risk a legal contest. One such competitor was Glenn Curtiss, a motorcycle maker turned airplane designer who became one of the Wrights’ fiercest competitors. Fitting his aircraft with movable flaps called ailerons instead of a wing-warping mechanism, Curtiss hoped to steer clear of the Wrights’ patent. But because his aircraft operated according to the same principle of control, the Wrights believed they had a case.

Curtiss was not alone in his legal woes, however. Between 1909, when the Wrights first sued Curtiss, and 1917, when the Wrights’ patent war sputtered to a halt, the brothers filed suit against a veritable Who’s Who of early aviators.

The financial results of these lawsuits were mixed. A German judge ruled against the Wrights. A French court ruled in their favor. And, in the U.S., judges twice ruled against Curtiss—though, as in France, legal wrangling prevented the brothers from collecting significant royalties prior to the termination of the patent war. Meanwhile, the ever-present threat of a sternly worded letter from the Wrights’ lawyers convinced more timid competitors to swallow their pride and pay the brothers massive fees for the opportunity to exhibit their aircraft.

But while the financial results of the patent war were mixed, its impact on the state of American aviation was indisputably negative. Even before Wilbur’s death in 1912, during a period of intense litigation, the Wrights had sorely neglected R&D—so much so that by 1915, when Orville sold the company he and his brother had founded, their aircraft were derided as dangerous and obsolete. Once the envy of the skies, Wright aircraft had become an embarrassment. Meanwhile, even though other American designers continued to develop impressive innovations during the period of the patent wars, the American aircraft industry as a whole was stunted by the litigation. In fact, by the time the United States entered World War I in 1917, the state of domestic aviation was so dismal that the U.S. government could not find a single American aircraft fit for military service. Thus, the country that invented powered flight would take to Europe’s war-torn skies in foreign-made craft.

Distressed by this state of affairs, an up-and-coming politician named Franklin Delano Roosevelt, then serving as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, decided to take action. Strong-arming key players throughout the American aeronautic industry, Roosevelt convinced intellectual property holders to form a patent pool that would allow airplane makers to use one another’s technologies for a modest fee. In doing so, Roosevelt effectively brought the patent war to a long overdue conclusion.

To say that the Wrights lost the patent war would be a mistake. Orville and Wilbur collected huge sums in exhibition fees from frightened competitors, despite the absence of a clear ruling in their favor. Still, in the long run, a variety of forces – historical momentum among the most important – lined up against the Wrights, ensuring that the aeronautical principles they had uncovered belonged to all.

Today, then, we should remember the Wrights’ historic first flight. But we should also remember the years of needless, bitter legal conflict in which they embroiled the industry they founded.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Sean Trainor has a Ph.D. in History & Women’s Studies from Penn State University. He teaches history and humanities at Santa Fe College and blogs at seantrainor.org.

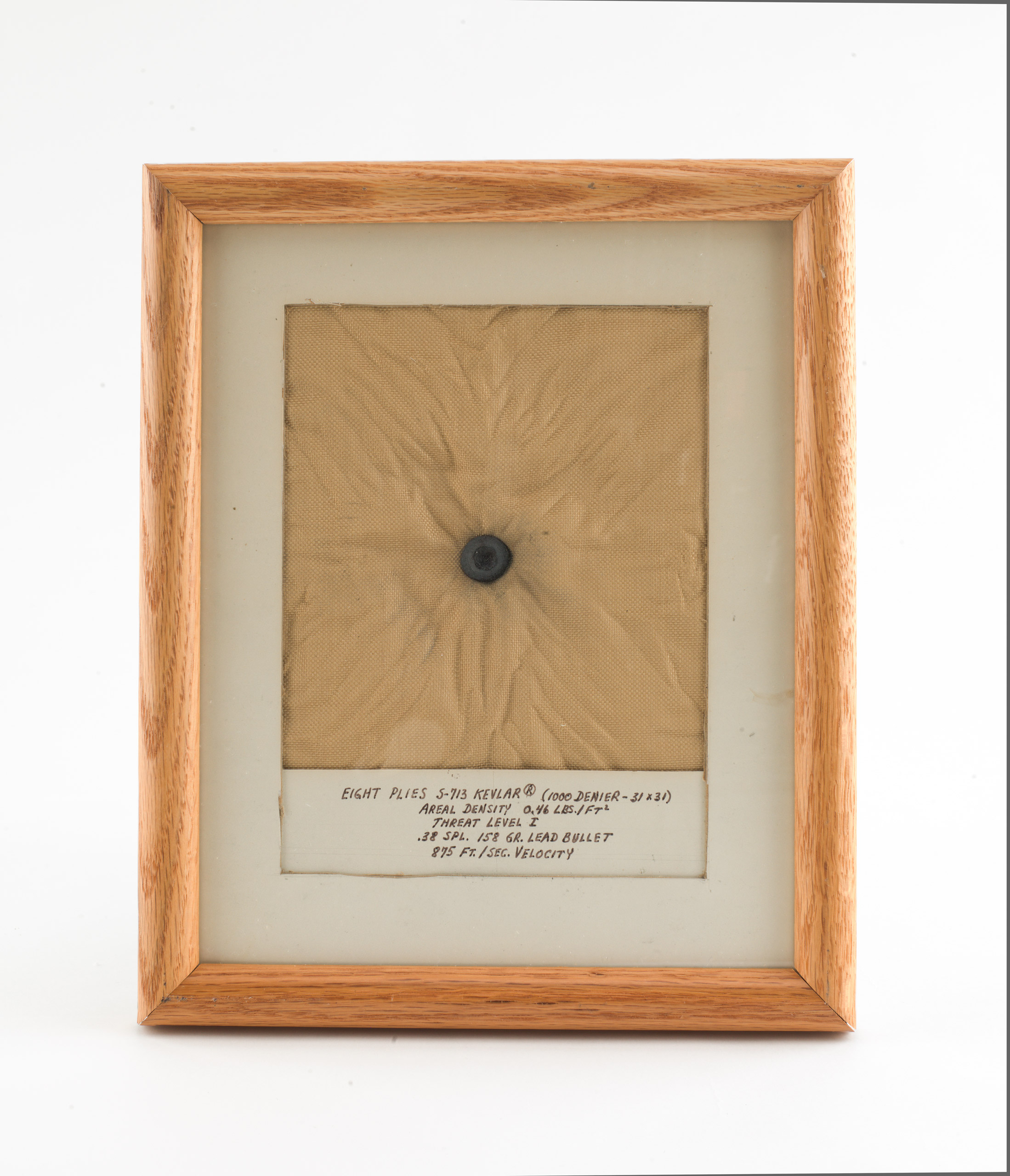

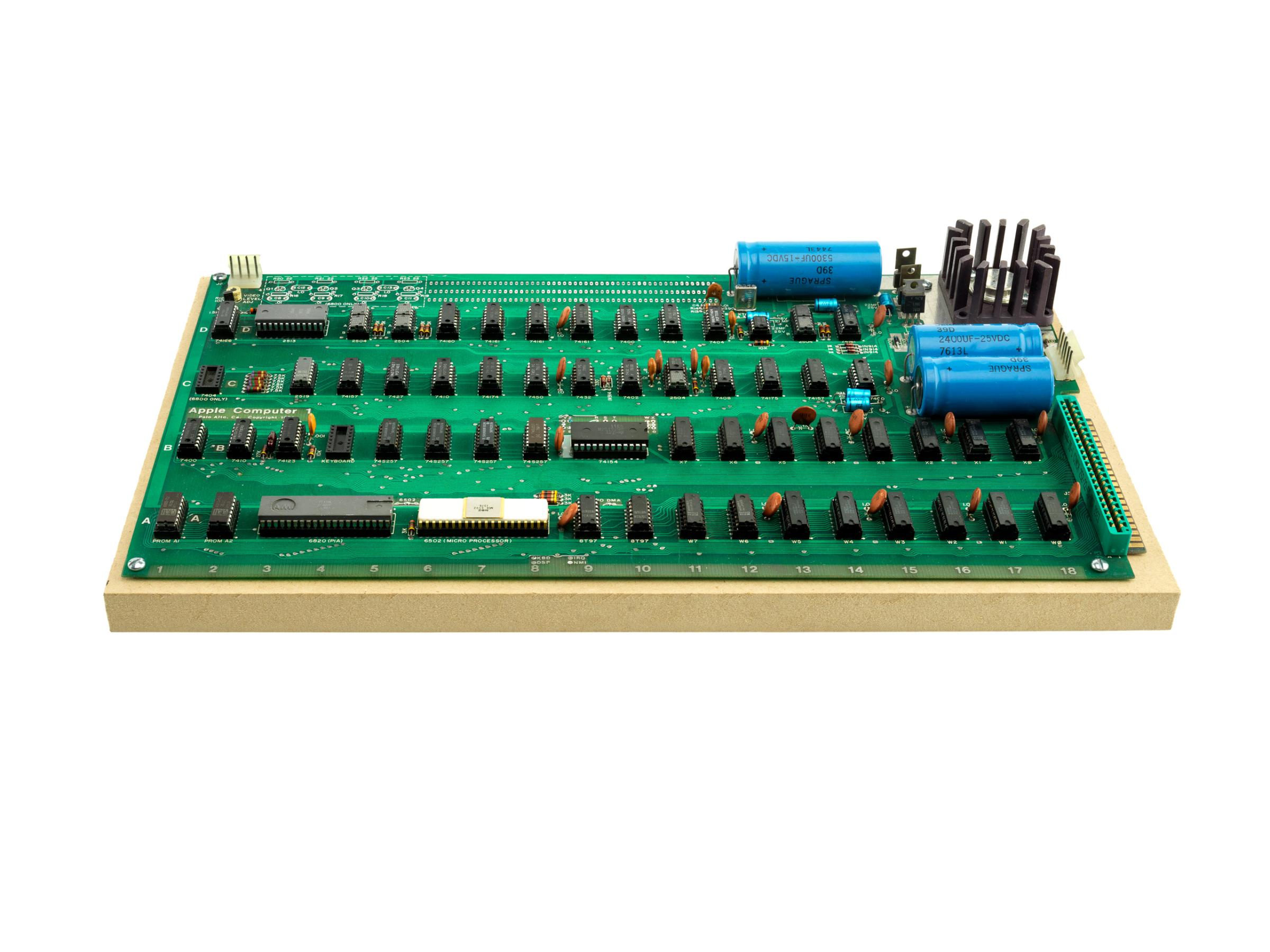

See Original Models of the Apple I and Other Iconic American Inventions

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com