In December 1948, Patricia Highsmith—then twenty-seven years old and fetching in an offbeat style, razor thin, tall, usually dressed in a white Oxford shirt from Brooks Brothers—was working as a temporary salesclerk in the toy department at Bloomingdale’s in Manhattan. It was a rather bleak day, with showers making the mild temperatures less pleasant. In any case, it was a day that she would never forget. A tall blonde woman in her late thirties, reeking of class, wearing a mink coat, approached the counter to inquire about a toy for her daughter. Dazzled by the woman’s cool beauty and presence, Highsmith struggled to focus on the simple request. A few words, no more, were exchanged. In a poof, it seemed, this vision of beauty exited the art deco store on Lexington Avenue. Only her perfume and presence lingered for Highsmith, made palpable by the fact that she had near to hand the woman’s name and home address on a slip of paper for shipping purposes.

The day after this fevered encounter, Highsmith wrote a plot outline for a novel. “It flowed from my pen as from nowhere,” she recalled. In her journal she recorded the intensity of the experience: “I see her the same instant she sees me, and instantly, I love her, . . . Instantly, I am terrified, because I know she knows I am terrified and that I love her.” In a chilling observation, Highsmith admitted, “Murder is a kind of love, a kind of possessing.”

Such was the stuff of Highsmith’s art and life, dedicated as it was to turning things on their heads, to dissolving lines between madness and sanity, and to an upswell of excess.

The name of the woman who skittered into Highsmith’s life that day in Bloomingdale’s was Kathleen Senn. Highsmith spent hours huddled over her notebooks and typewriter until she had imaged Senn as the character Carol Aird in the novel The Price of Salt. Twice, however, Highsmith indulged her obsessive curiosity about the real Mrs. Senn. As she admitted about herself, “Obsessions are the only things that matter.” In fact, Highsmith stalked Senn. On June 30, 1950, one day after completing a first draft of Price of Salt, Highsmith took a train from Penn Station to Ridgewood, New Jersey. She recorded in her journal: “Today, feeling quite odd—like a murderer in a novel, I boarded the train.” Highsmith arrived at the Ridgewood train station, gulped down a couple of stiff drinks, then clambered aboard a bus to find the house—and perhaps steal a glimpse of the divine Mrs. Senn. Exiting the bus, she moved conspicuously along streets with tony homes. Solitary walkers along the tree-lined streets were unusual, and Highsmith feared she would be discovered and revealed as a voyeur. Highsmith failed to locate Senn’s upscale Normandy Tudor home, which bustled with turrets and stonework. She liked to think, however, that a passing automobile had been driven by the object of her attention. The experience, Highsmith wrote, “shook me physically and left me limp.”

Highsmith’s infatuation with Senn had convinced her that lesbianism was natural and ripe with possibilities. Confidence in the writing of the new novel, however, coexisted with shame. The book did bear, she remarked, a “close truthfulness” to aspects of her life, but it promised little for her reputation. As the novel hurried to publication, Highsmith drank so much that weeks in her life had dissolved into a “blank in memory.” Published under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, The Price of Salt was reissued a year later as a Bantam paperback edition; its lurid cover captured all the tropes then common for the lesbian novel genre. A beautiful young woman sits seductively on a couch. Looming over her is a beautiful older woman, one hand holding a cigarette, the other hand placed fondly on the younger girl’s shoulder. In the distance, rushing to put a stop to the seduction is a handsome young man. “Bad” girls were meant to get caught and punished, according to historian Jaye Zimet: “The lesbian gets her due . . . marriage, insanity or . . . suicide.”

Being a lesbian in the United States in the late 1940s and 1950s was, as Zimet makes clear, difficult and dangerous. The pressure was great from family and friends to conform to the heterosexual norm. And the consequences of refusal could be immense. Gay men and women were considered not only perverts but security risks; thousands of government workers were dismissed from service during the “lavender scare” for being presumed to be gay. Women in the postwar years were expected to marry and raise a family, to anchor their existence within the happy confines of the home.

In some ways, however, lesbianism in this period was emerging from the shadows. The Kinsey Report on women’s sexuality, published in 1952, found that 6 percent of women between the ages of twenty and thirty-five were lesbian in inclination. As more young women with such an orientation gravitated to urban centers in search of careers and liberation, they discovered lesbian bars, where a culture of freedom was tempered by fear of harassment. Highsmith gained entry into a world of wealthy lesbians who threw lavish parties in their homes. This rich environment teemed with talented and wealthy women. For those unwilling or unable to enter into either of these worlds, some titillation might be gained from pulp fiction depicting female relationships.

The Price of Salt centered on a lesbian relationship. But it went beyond expectations of pulp fiction. Lesbians invariably bowed to the heterosexual demands of society—or, if unrepentant, experienced its wrath. Highsmith’s novel was remarkable both for its tender depiction of lesbian love and for its sensitivity to shifting balances and power relations between lovers. Most of all, as Highsmith wrote later, “It had a happy ending for its two main characters, or at least they were going to try to have a future together.” This emphasis on pleasure, without guilt or punishment, was part of the New Sensibility that was central to writers such as Allen Ginsberg, Gore Vidal, and Samuel R. Delany. So ends Highsmith’s novel, without a single murder or suicide taking place. And no punishment for the lesbians, only the prospect of a life together.

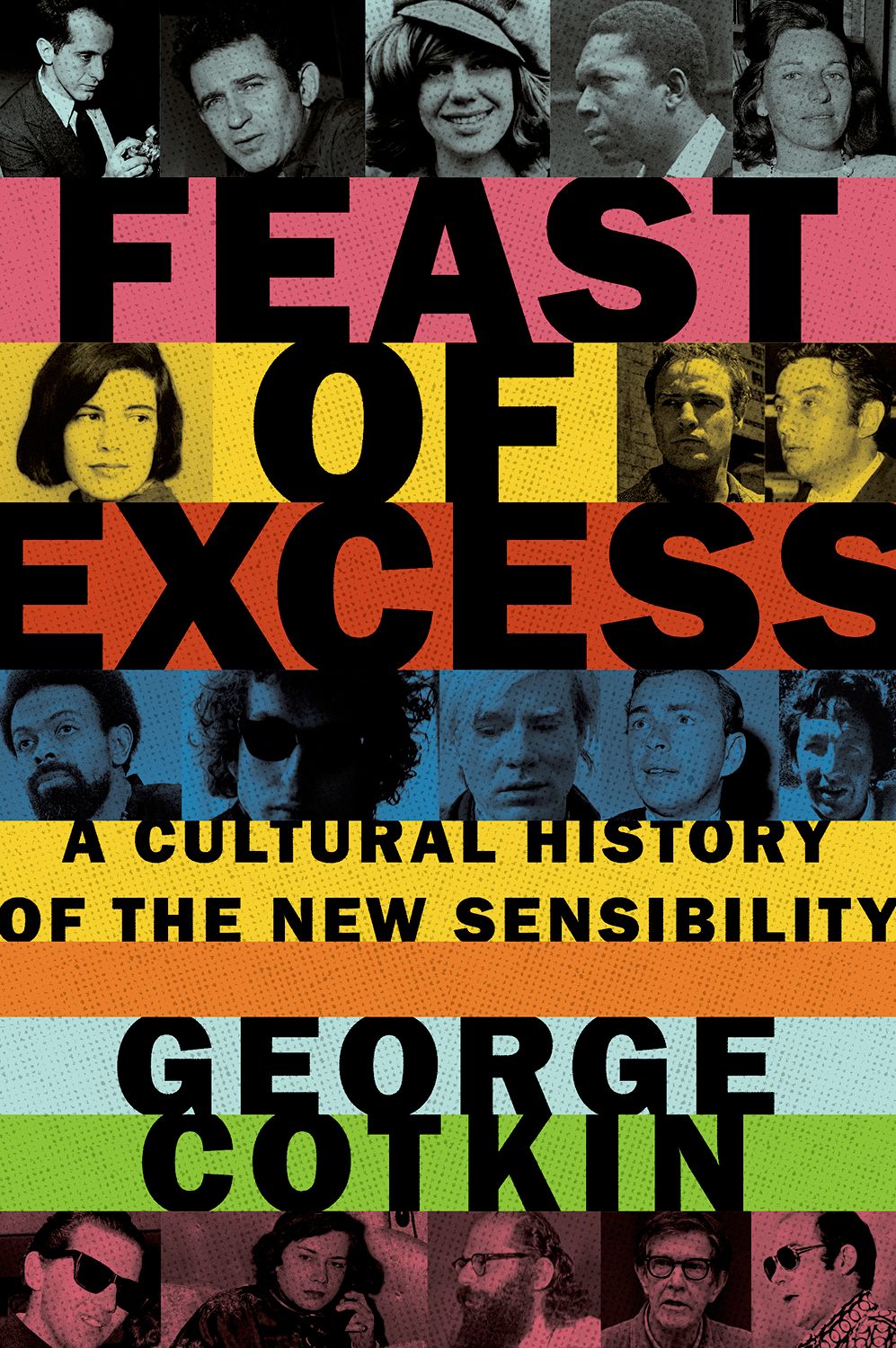

Adapted from FEAST OF EXCESS: A Cultural History of the New Sensibility by George Cotkin with permission from Oxford University Press, Inc. Copyright © 2016 by George Cotkin.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com