Women who are infected with a certain parasitic worm may be more likely to become pregnant, according to a new study.

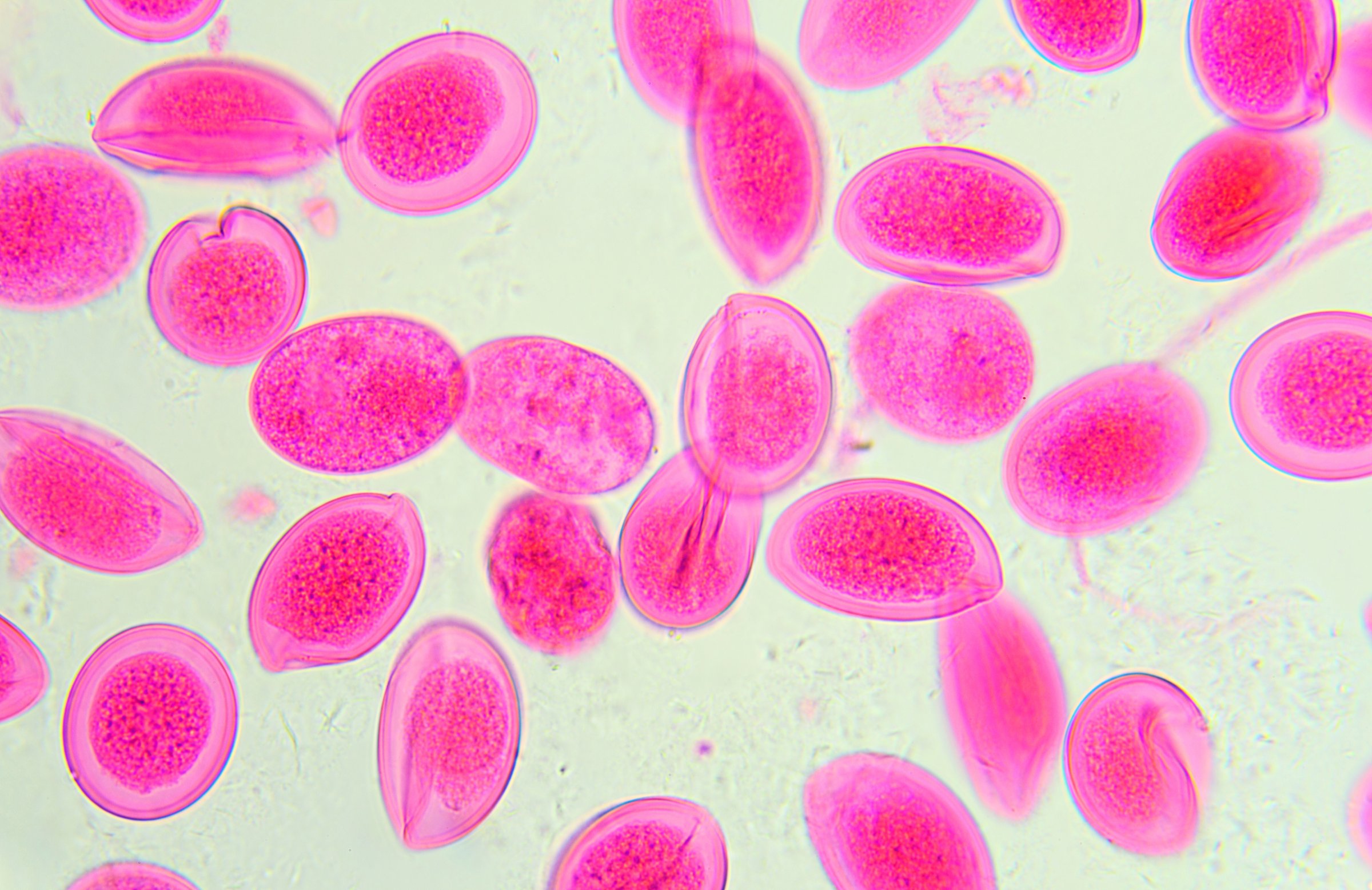

The study, published in Science on Friday, studied 986 Tsimane women in Bolivia for nine years, and found that women infected with the roundworm species scaris lumbricoides had about two more children than women without the worm (Tsimane women have an average of 10 children in general). The researchers noted that the infection is associated with shortened intervals between births, and with earlier first pregnancies.

“We think the effects we see are probably due to these infections altering women’s immune systems, such that they become more or less friendly towards a pregnancy,” University of California Santa Barbara professor Aaron Blackwell, one of the study’s authors, told the BBC. The researchers suggested that a suppressed immune system due to the infection may make the body less likely to reject a fetus.

Blackwell added that further research is necessary before there could be any practical use of this potential link between the roundworm infection and fertility.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Julia Zorthian at julia.zorthian@time.com