In recent days, as protests over racial issues at the University of Missouri have resulted in the resignation of university president Tim Wolfe, and as thousands of Yale students organized a march in response to racial divisions on their own campus, it’s been easy to compare this latest wave of campus activism with previous such moments in American history.

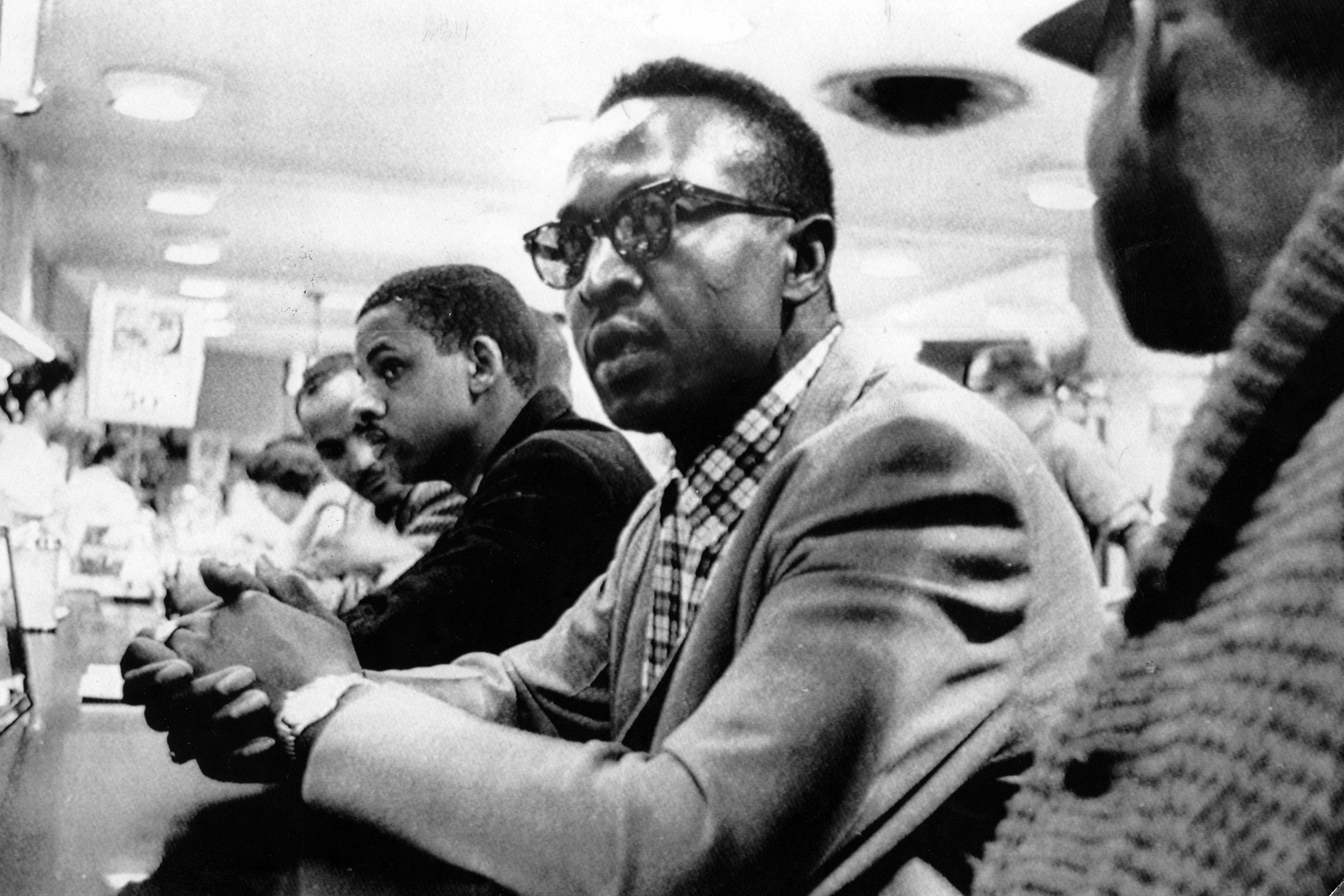

The anti-war demonstrations that swept the nation during the late 1960s and ’70s remain perhaps the most famous moment of American student activism—and, if the comparison holds, they provide at least one reason for today’s activists to be optimistic about the larger implications of their visibility.

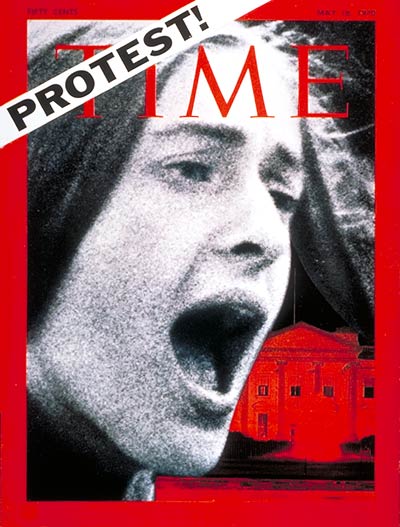

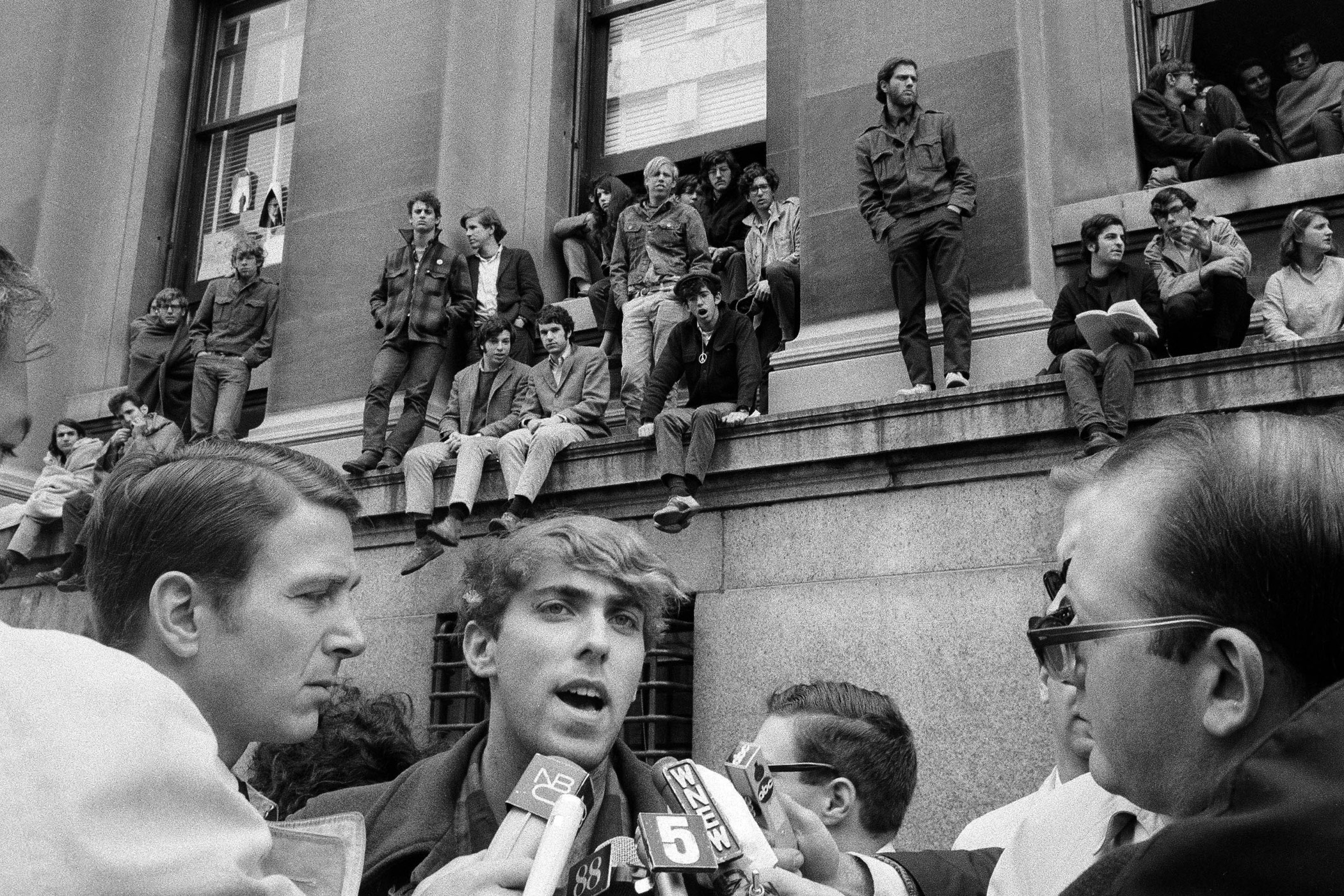

In 1970, TIME featured the student protests in a cover story at one of the most volatile moments of the anti-war movement. The Kent State shootings had only just occurred, sparking a national outcry among students, and there could no longer be any doubt that something noteworthy was happening on America’s campuses. By TIME’s count, 441 colleges and universities across the country were affected by post-Kent State protests, and some of them shut down entirely.

At the largely conservative University of Nebraska, students occupied the school’s ROTC headquarters. At Duke Law School, Nixon’s portrait was removed from the wall and put in storage. At Yale, students wore suits and ties to their commencement so they could donate their cap-and-gown fees to benefit anti-war political candidates. One student group advocated that America’s collegians stop drinking soda until the war ends, figuring that anti-war advocacy from Pepsi and Coke would speak louder than they could alone.

But, as TIME noted, it wasn’t just a matter of the protests being widespread. “All through the restive winter and early spring, the campus atmosphere had been heavy with intimations of bomb plots, and sometimes with actual whiffs of black powder,” the story observed. “Last week’s actions suddenly changed much of that mood.”

When the protests became a national cause, especially with the galvanizing incident at Kent State, more moderate students began to participate. The more radical fringes were “simply overwhelmed” by the other protesters, TIME noted, and a new strategy emerged. It may sound simplistic to say that protests with more people are more likely to be heard, but this moment in history shows that the converse is true too: it had been very hard to attract those who didn’t identify as activists to a movement that was seen as radical or hopeless. The participation by moderate protesters came after opposition to war no longer seemed like an extreme position, and when it seemed like that opposition had a chance to be heard.

The University of Missouri’s football team is a perfect example from today’s world: whether they identify as activists or not, the football players aren’t typically on the extreme fringes of campus culture, and yet they joined the protests by refusing to play until the school’s president resigned.

As a result, more—and more visible—protests on college campuses can be read as evidence that the protesters are increasingly hopeful that they can have an effect, and that the system in which they live, no matter what they think of it at the moment, is capable of progress in the direction they desire.

When the 1970 protests hit their peak, the students illustrated that shift. When 1,000 of them visited Capitol Hill, they cheered when Indiana Senator Birch Bayh summed up their request: “We can make this system responsive from within instead of trying to destroy it from without.”

Though the Vietnam War wouldn’t officially end for another five years—and though the protests would not ultimately be the factor that doomed Nixon’s presidency—the new tactic did pay off. By the end of that week, several students who had gone to Washington to speak with their Congressmen ended up with an invitation to the oval office. While Nixon defended his recent decision to involve the U.S. military in Cambodia in addition to Vietnam, he used a conciliatory tone in in discussing the protests. It was no longer possible for the students to be ignored and, 45 years later, their impact on American history remains clear.

Read the full 1970 cover story, here in the TIME Vault: At War With War

See 7 Times Student Activists Created Change

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com