Congressional leaders struck a deal with the White House Monday night that would fund the government and raise the debt ceiling through the 2016 elections, effectively removing the final fiscal cliff from President Barack Obama’s tenure.

Congressional leaders are aiming to pass the bill, which will face its first hurdle on the House floor Tuesday, through the lower chamber before Paul Ryan in sworn in as the 62nd speaker on Thursday, thus clearing most of the controversial legislation pending before Congress through the election, or “cleaning out the barns,” as House Speaker John Boehner pledged to do before he retires at the end of the month.

On Monday night, as both chambers returned for votes in Washington, leaders briefed members about the bones of the deal. Republican senators left largely positive about the deal. “There was no orthopedist in the room,” chuckled Sen. Johnny Isakson, a Georgia Republican. “There were no broken bones. Not even a sprain so far as I saw.”

Read More: The Four Biggest Challenges for Speaker Ryan

House Republicans were less impressed, especially the right-wing Freedom Caucus, a 40-member group who in the last month took down Boehner and his heir apparent Kevin McCarthy in their opposition to the establishment. “You’ve got five people negotiating this thing,” scoffed Rep. David Brat, a Virginia Tea Partier who unseated Majority Leader Eric Cantor in a primary last year. “I thought Republicans had the House and the Senate, that’s not clear to me from this deal.” Freedom Caucus members emerging from Monday night’s meeting called on incoming speaker Ryan to oppose the deal.

Ryan, meanwhile, had little to say about the bill. His office referred inquiries to Boehner’s office and noted that a final agreement had yet to be made. But it’s hard to imagine Ryan moving to block what is essentially Boehner’s parting gift to his successor.

If passed into law, the deal would clear the decks of controversial measures for both Ryan and the Republican presidential candidates, many of who have watched Boehner’s abdication, and the downfall of McCarthy, roil the party at a time when it needs to begin uniting behind a platform and a candidate. It will give Ryan more than a year of breathing room to establish his own speakership and governing style.

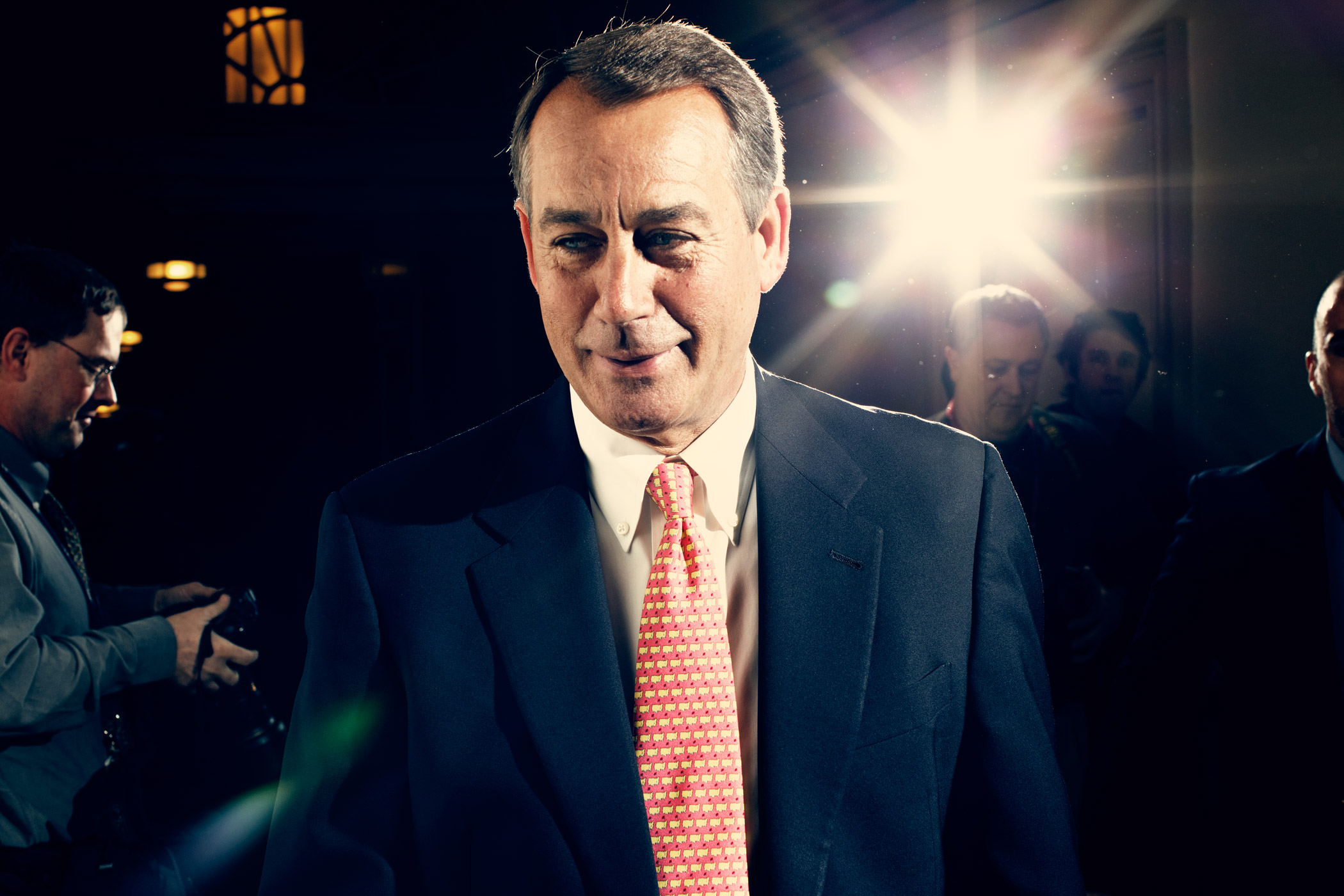

Highlights from the Career of House Speaker John Boehner in Pictures

The agreement would mitigate the effects of the sequester—across the board cuts to the Pentagon and entitlements enacted when Congress failed to resolve the 2011 fiscal cliff—for fiscal year 2016 to the tune of $25 billion apiece for the Pentagon and entitlements and $15 billion each for fiscal year 2017.

It would also add $16 billion in additional discretionary spending, also equally split, for each fiscal year. The $32 billion in additional funds, which will be deposited in the Pentagon’s overseas contingency operations account—essentially a giant petty cash fund—would not be offset. Finally, it would mitigate projected cuts by 53% to Medicare Part B payments.

The bill would be partially offset, according to staff from both sides of the aisle, using spectrum sales, crop subsidy reforms, recalculating the formula for Social Security disability payments and by potentially adding a year to the back end of the sequester. But as it currently stands it would only be about 70% offset, something that will surely enrage fiscal conservatives. The rest would draw from deficit spending.

In years past, this was usually the moment the deal would collapse: House and Senate negotiators would come to a bipartisan deal only to see it derailed by conservative opposition in the House. But this time, Boehner has nothing to lose if he breaks the so-called Hastert rule and passes the deal on the backs of Democratic votes. He will be gone from Congress by the end of the week. Boehner had always planned to pass the baton to McCarthy by the end of the year, but he moved that timeline up when he saw he could lose a confidence vote in his speakership.

“John intended to get the two-year budget and the debt ceiling done before he left with his departure date at the end of the year and I think when he moved up his departure date he was in a much better position to put together what was going to be a tough vote for a lot of Republicans and take the blame for us,” says Sen. Richard Burr, a North Carolina Republican and one of Boehner’s closest friends. “So it shouldn’t shock us that’s who he is.”

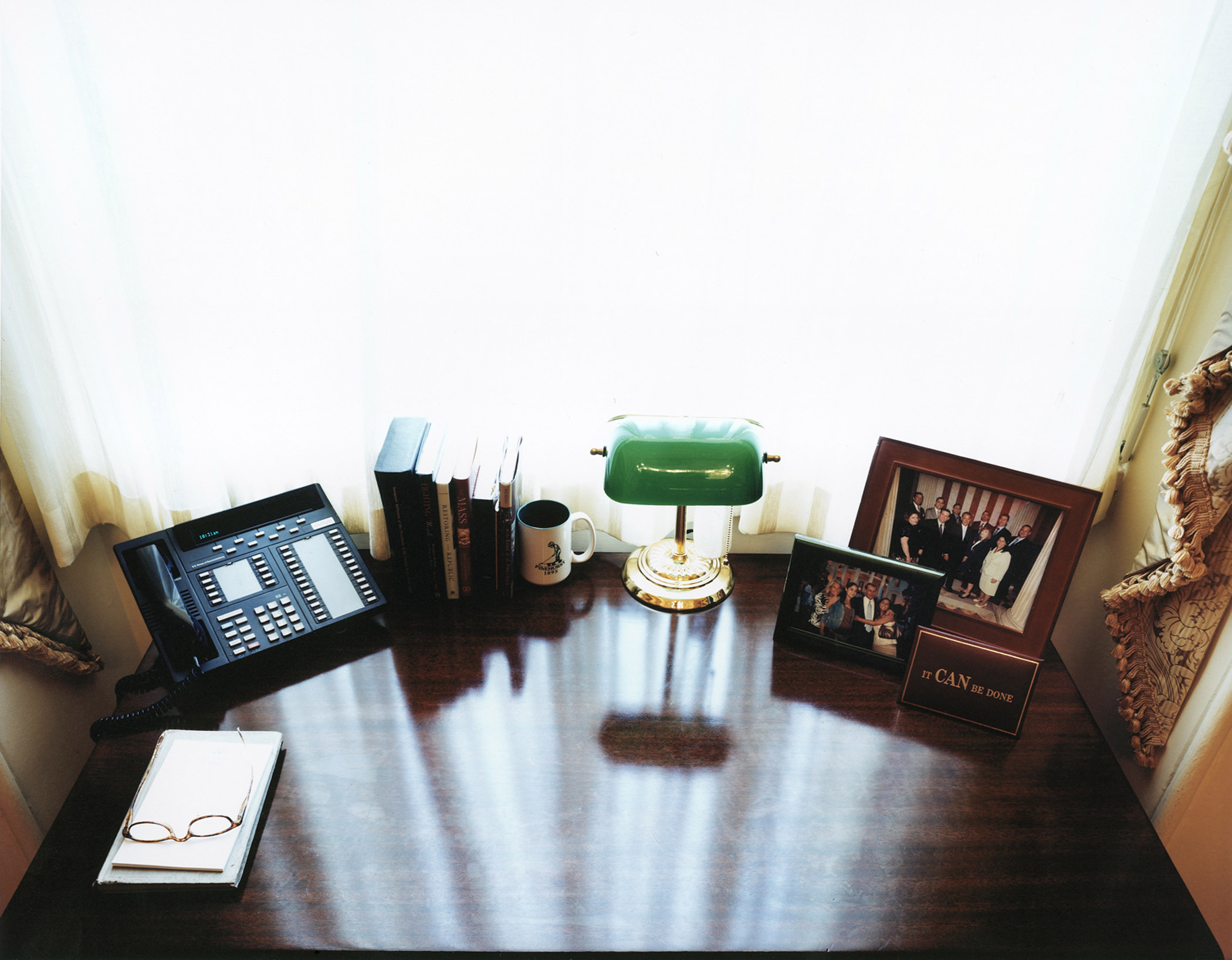

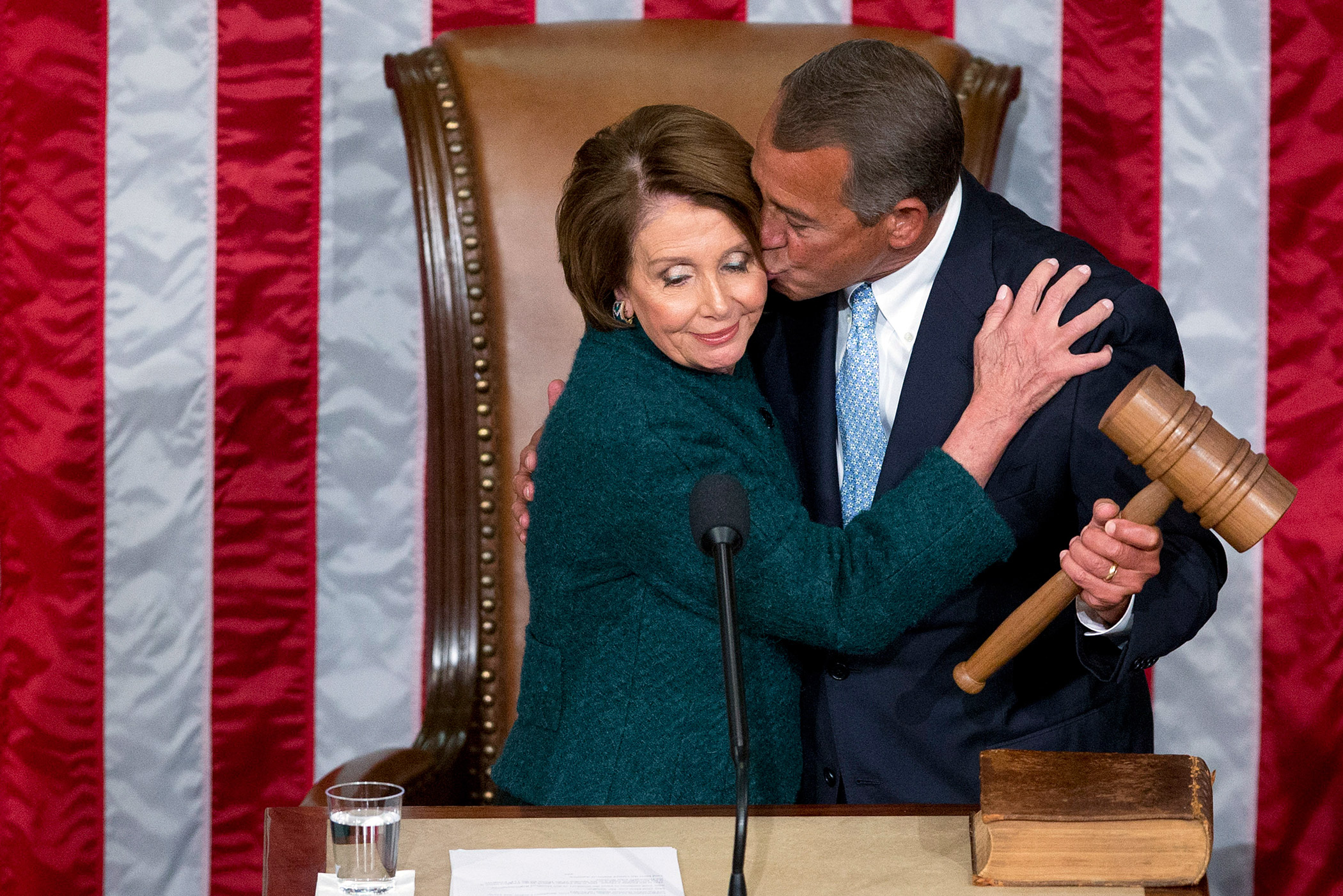

In his 24 years in Congress, Boehner always wanted to be a dealmaker. From his first days in office, the only portrait he had hanging on his wall was one of the last speaker from Ohio, Nicholas Longworth, who famously held nightly bipartisan drinks with his Democratic counterpart, John Nance Garner, known as the “Bureau of Education.”

But Boehner’s Faustian bargain in 2010, empowering Tea Party candidates in order to take back the House, resulted in another kind of education altogether, one that proved politically fatal for the old-school, institutionalist Boehner. And so, having been forced from his perch by a group of unruly conservatives, punished for being too much like his idol Longworth in passing bipartisan compromises out of the House, Boehner is finally poised to do what he never could freely do as Speaker: pass important legislation

In doing so, he saves the GOP from a bruising intra-party battle—or at least punts it to after the election when it would, theoretically, do less political damage.

What will Boehner do when he’s done committing political hari-kari?

“Go to Disneyland, I imagine!” laughs Burr.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com