The Legend of Zelda: Tri Force Heroes may be the quirkiest Zelda game idea since Kazunobu Shimizu flipped us sideways almost three decades ago in The Adventure of Link. I mean more than the shadow slinking in last year’s A Link Between Worlds, or the Groundhog Day resets in Majora’s Mask. The latter had its creepy celestial inducement along with the franchise’s weirdest story, sure. But the game still played more or less like Ocarina of Time.

Tri Force Heroes by comparison feels both unique to the franchise and at the same time multiple shades of different depending on your approach. There’s multiplayer, of course, the game’s basic reason to exist. But even there you’re faced with a question: which version of multiplayer?

You can play with two others nearby, for instance, the three of you hunched over your handhelds shouting ideas or directives as you attempt to cooperatively solve spatial conundrums intertwined with the game’s shadowbox 3D effect. But then there’s nothing stopping experienced players from blurting out a level’s secrets in this mode.

You can alternatively play the game online with anyone, anywhere. But then you’re limited to communicating through a handful of buttons situated on the 3DS’s bottom screen that trigger waggish gestures in the game. The absence of voice chat prevents vets from blabbing solutions, but those buttons challenge players to collaborate in often hairy circumstances without the benefits of natural language.

Or you can just play Tri Force Heroes solo, controlling all three characters yourself (though only one at a time), at which point the game morphs into a spatial puzzle game meets a real-time strategy game–utterly different from the multiplayer experiences.

I’m not saying it always works, or that certain single player puzzles don’t feel ill-suited to playing solo. But I think it’s fascinating that Nintendo managed to jam three very different experiences into a single game. I had a chance to ask the game’s producer, Eiji Aonuma, as well as director Hiromasa Shikata about some of those design choices. Here’s what they told me, lightly edited for clarity.

Your little band doesn’t follow you around in single-player mode because it violates key design principles

“We did think about the characters following each other automatically, but we have three different characters in the game with three different items,” says Shikata. “So we had problems like who’s going to be left behind, or who are we going to totem, and so it got much more difficult [players can form “totems” by stacking characters up to three high to solve height-related puzzles]. And also, the single-player was supposed to be a learning experience for the multiplayer, so we didn’t want to make single-player something that was super easy, where everyone would just play the single-player instead of the multiplayer.”

“We released The Four Swords for the 25th anniversary of Zelda, and in that game, in single-player mode, we had the characters follow each other,” adds Aonuma. “But then it became a single-player experience, and that didn’t create the multiplayer experience we wanted. The team agreed, and so this time, that’s why we came to this conclusion.”

The team originally resisted the idea of adding single-player

“When we started, I didn’t have any thoughts of creating a single-player mode, because I was focused on a three-player mode that’s fun,” says Shikata. “So one day, Aonuma-san steps in and says ‘Can you make a single-player for this?’ And I was thinking ‘Oh no, no, that’s not . . . All of a sudden? Wow, can we?’ And so we went back and forth about it.”

“When I created Marvelous [an action-adventure for the Super Nintendo released in Japan in 1996], it was a three-player game, and so I said ‘How about something like that?'” says Aonuma.

“Yeah, so we thought maybe it’s not possible, but then we started talking about it, and we said ‘How about one course, can we do it on just one?’ And that led to ‘Can we do it on all courses?’ And it turned out it was doable. So ultimately what happened was, we were able to create a new way of playing the game that was different from the multiplayer experience.”

“I also think that because we have the multiplayer experience, the single-player stands out,” adds Aonuma. “And because we have all of these different ways of experiencing the game, these different design ideas, I think that’s what sets it apart.”

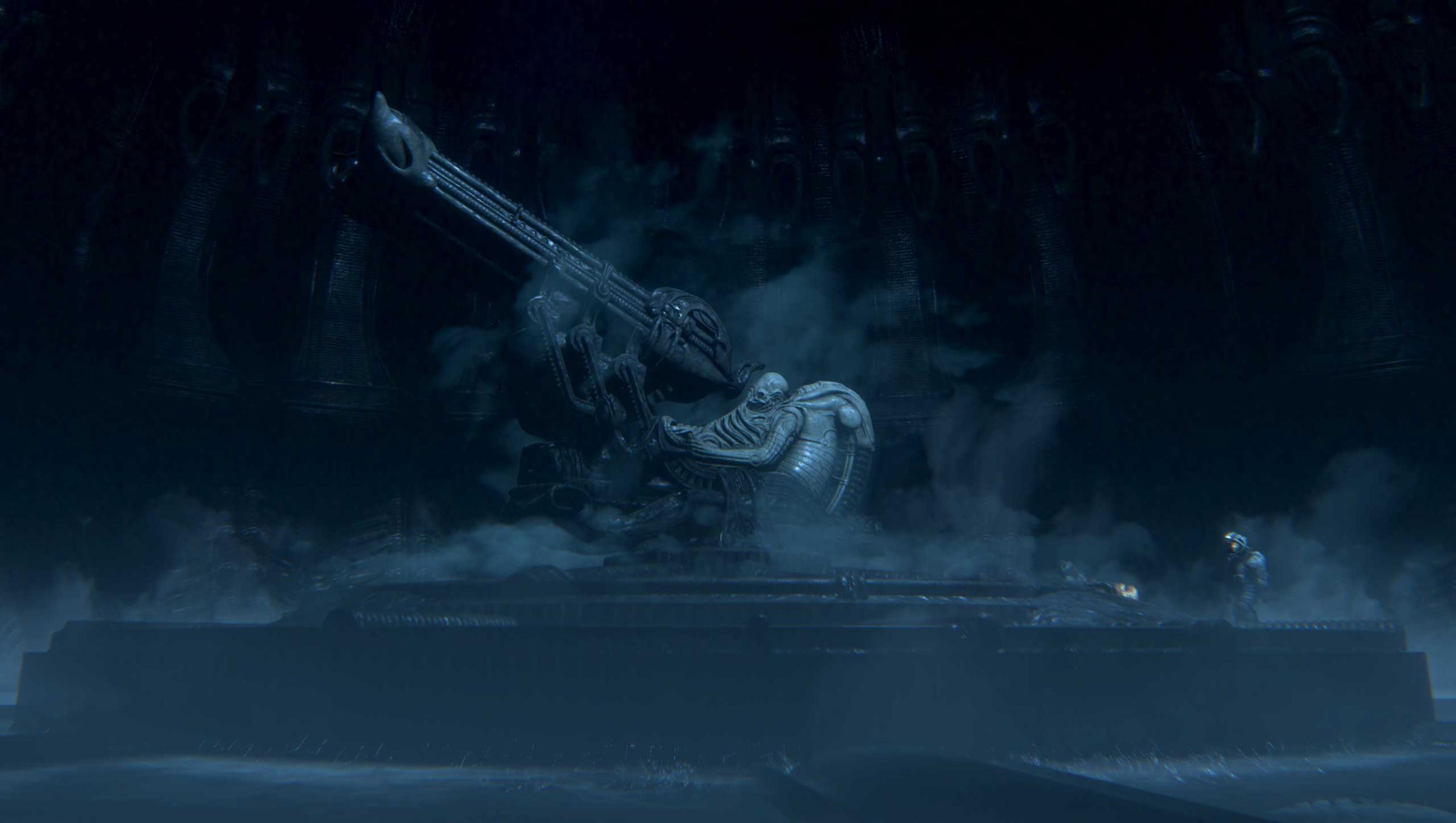

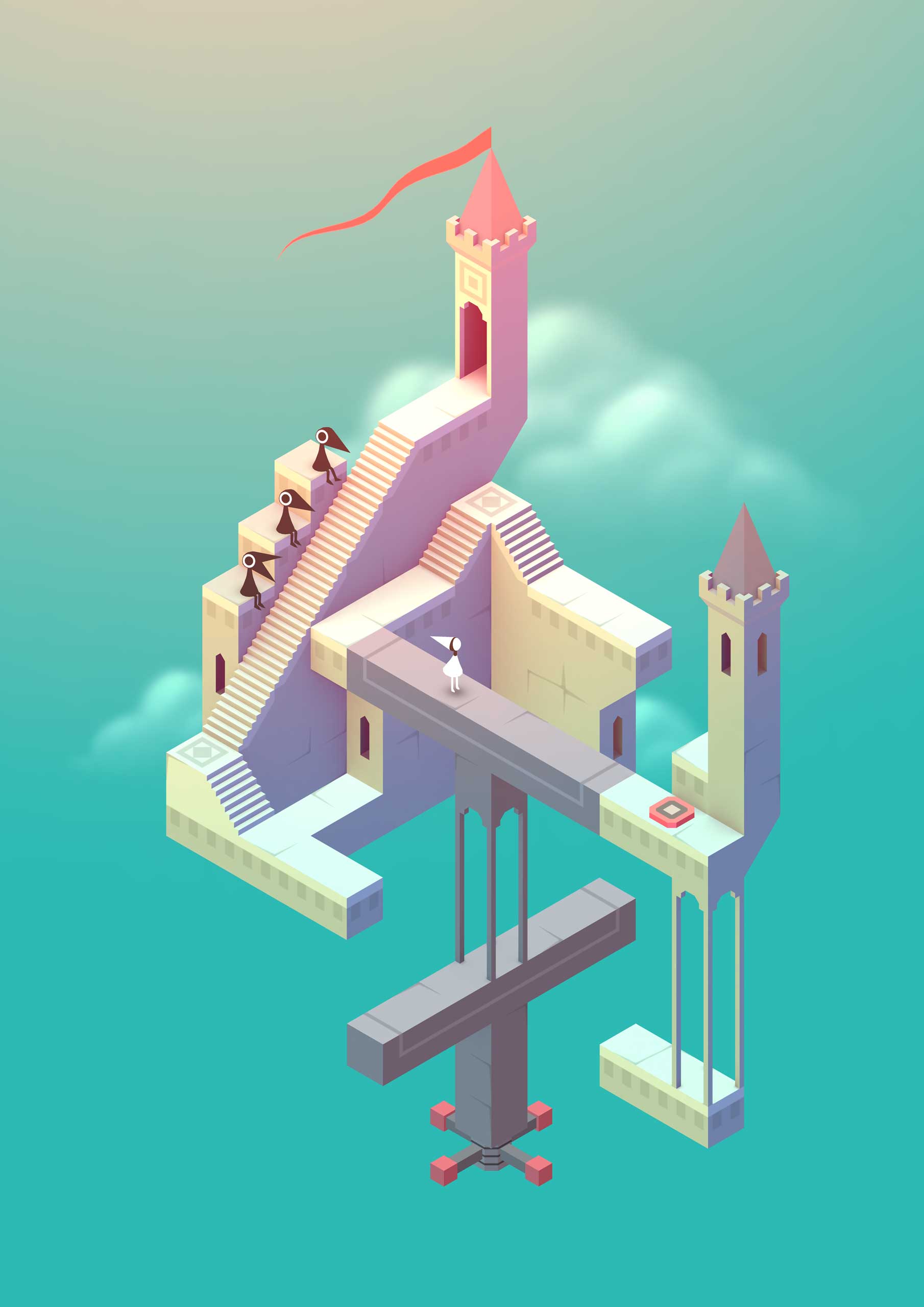

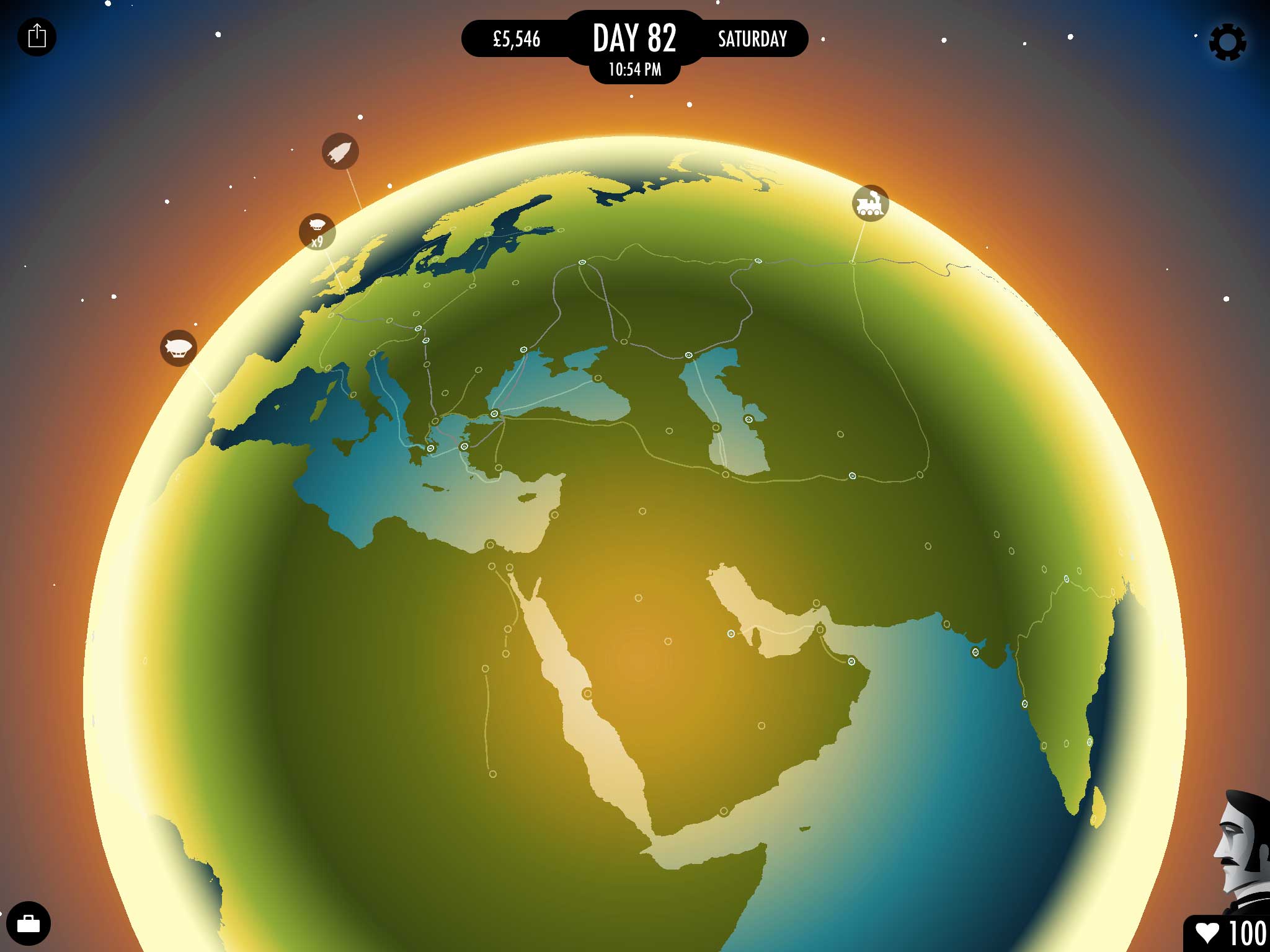

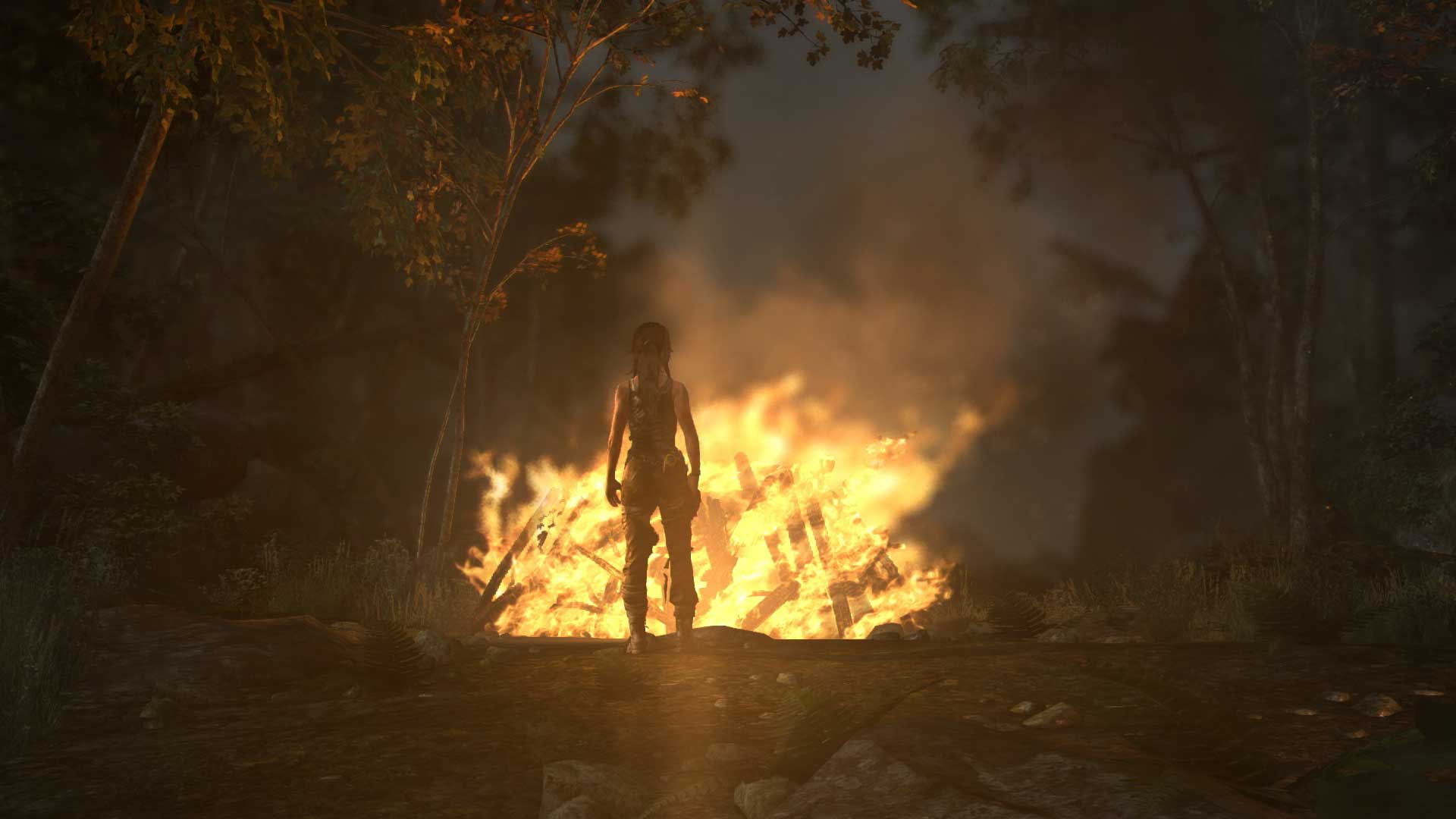

See The 15 Best Video Game Graphics of 2014

The 3DS’s stereoscopic 3D effect is, for once, almost essential

“Adding the height part to the game was very hard,” says Shikata. “We had to come up with special ways to show that height. For example, when we had a flame that was floating, we had to have little sparks coming out of it. Or if there was something in the landscape, we’d have to put a little mark or design to indicate it was higher positioned. But it was also the way we designed other elements in the game, like having an enemy stack three-high to indicate that players need to stack up to three as well to defeat it.”

“The 3DS allows us to use 3D in different ways, and we’ve been learning from previous games how to implement it,” adds Aonuma. “And so we thought, ‘How can we do this better in Tri Force Heroes?’ Also, what enabled us to make the big decision to focus on 3D, was the new version of the 3DS’s super stable 3D, which makes it easier to experience the 3D effect.”

The online communication icons were designed to encourage players to pay close attention to each other

“We considered voice chat for Internet play, but with voice, you’re going to see people that know the dungeon very well playing alongside people new to the dungeon,” says Shikata. “And when that happens, the people that know the dungeons are just going to explain what to do, and it won’t be as fun. So we wanted a different way to be able to communicate with other players.”

“Then we came up with the idea of the communication icons, and that became part of the puzzle solving, plus it’s kind of something where you have to use your imagination,” he adds. “If you already know how to solve the dungeon, you still have to figure out how to convey that to newcomers using the icons. It creates a game within a game.”

“By watching other players’ actions, it’s left to the imagination to construe what they’re communicating,” says Aonuma. “Or on the contrary, if someone hasn’t finished it, you might be able to tell by their actions ‘Oh, this person hasn’t done this stage yet.’ It was a way of figuring out what each player was doing, and of getting players to pay attention to what other players were doing.”

The characters are styled after The Wind Waker because they’re easier to see

“While we are definitely using the engine from A Link Between Worlds, we wanted to have all the players viewable, and so we actually adjusted the camera angle a little bit,” says Aonuma. “And when we thought about the full view of these characters, we decided The Wind Waker was the best, because [that visual approach is] the easiest to see.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com