In the end, Joe Biden just didn’t have it in him.

The 72-year-old Vice President said Wednesday at the White House that he would not make a third bid for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. The revelation came after weeks of public agonizing about whether he could muster the emotional strength to challenge his party’s frontrunner, Hillary Clinton.

“Unfortunately I believe we’re out of time, the time necessary to mount a winning campaign for the nomination,” Biden said in the White House’s Rose Garden, with wife Jill to his left and President Barack Obama to his right

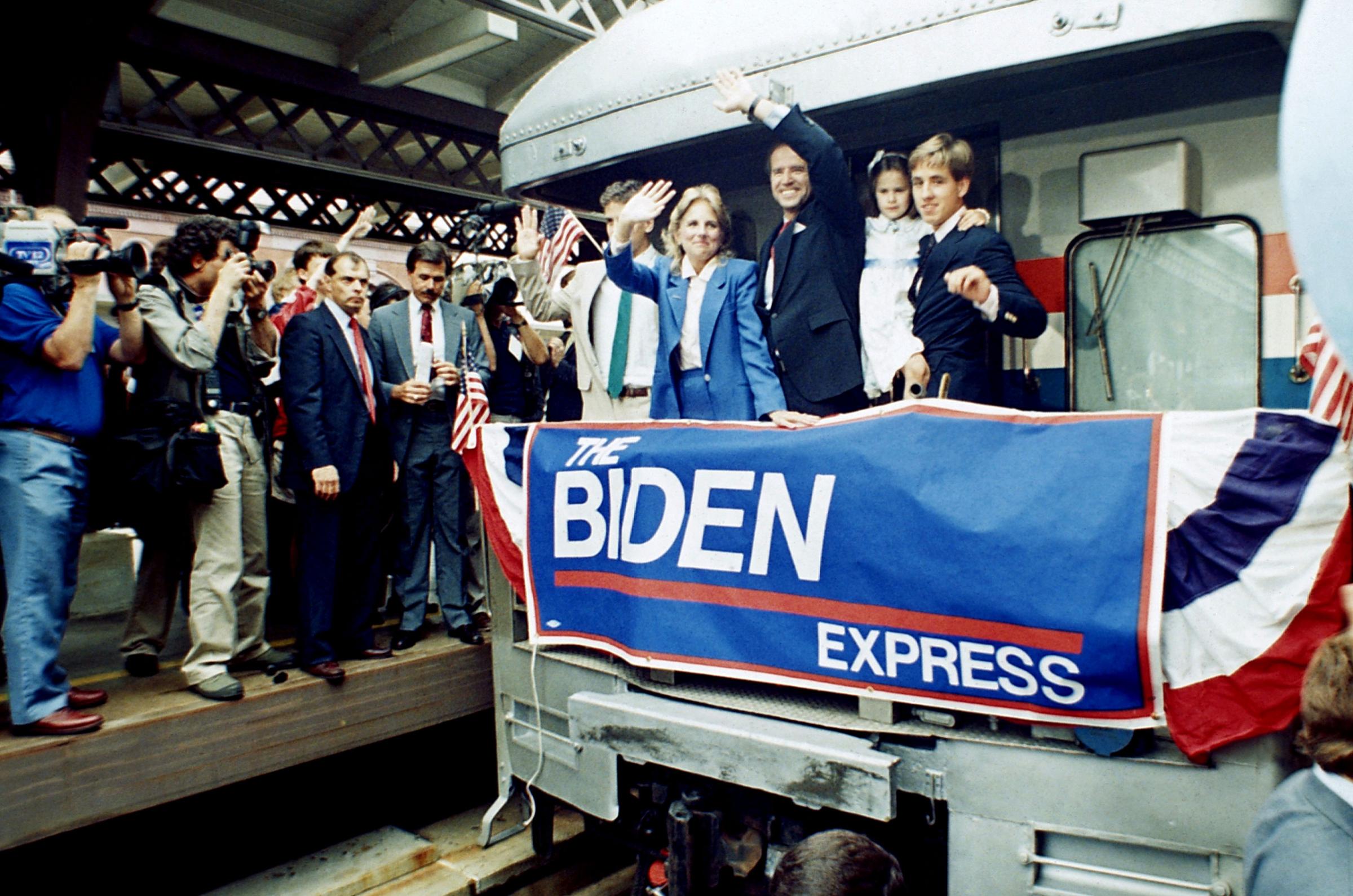

Biden’s announcement was the final word on whether he would try to honor a request from his late son that he take another stab at the job he first sought in 1988, at age 44. The presidency still appealed to Biden, but the pathway there, he recognized, was too difficult for a family still grieving Beau Biden, who lost his fight with brain cancer in May. Beau was two years old than the man he called “pop” when he made his first White House run.

He encouraged the other Democrats seeking the White House to support the legacy of President Obama. “They should run on this record,” he said. And he promised to push for progress on the issues that matter to him for the remainder of his time in office, calling in particular for a “moon shot” to fight cancer.

“While I will not be a candidate,” Biden said, “I will not be silent.” Just because Biden was not to appear on ballots, that did not mean he would retire his attack-dog instincts. After all, few in politics today can deliver a jab as effectively without looking like a bully.

“We intend to spend the next 15 months fighting for what we care about,” Biden said, hinting that he would use his office and his political skills to help Obama and the eventual Democratic nominee. “We are fully capable of accomplishing extraordinary things. … We can do so much more.”

In recent months, Biden has suggested he was serious about a run. He made campaign-style stops in swing states of Florida, Ohio and Michigan. He met with Democratic constituencies, including Jewish leaders, Hispanics and women. He started meeting with would-be-aides for a bid, although most left unclear if Biden were serious.

But the more his close advisers listened to Biden, the more they realized their preparations for a Biden 2016 campaign might be for naught. None begrudged the Vice President for the hours he had them meet at kitchen tables in Delaware and or porches in South Carolina. They were happy to use cell phone minutes as they kept tending calls from would-be aides or supporters. To a fault, his network of former aides remains fiercely loyal and protective. Almost everyone on these calls continued to believe that Biden would have been an exceptional President.

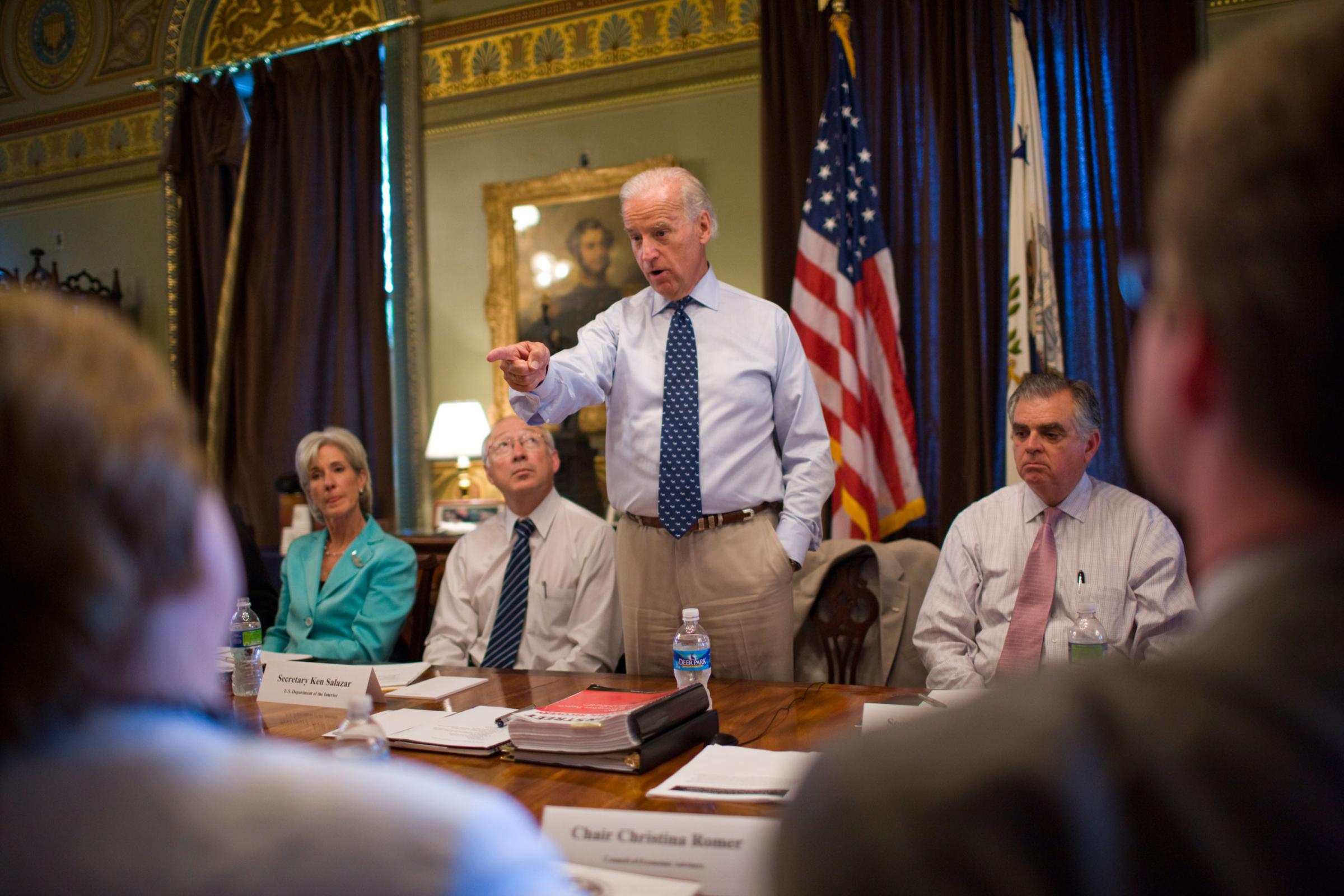

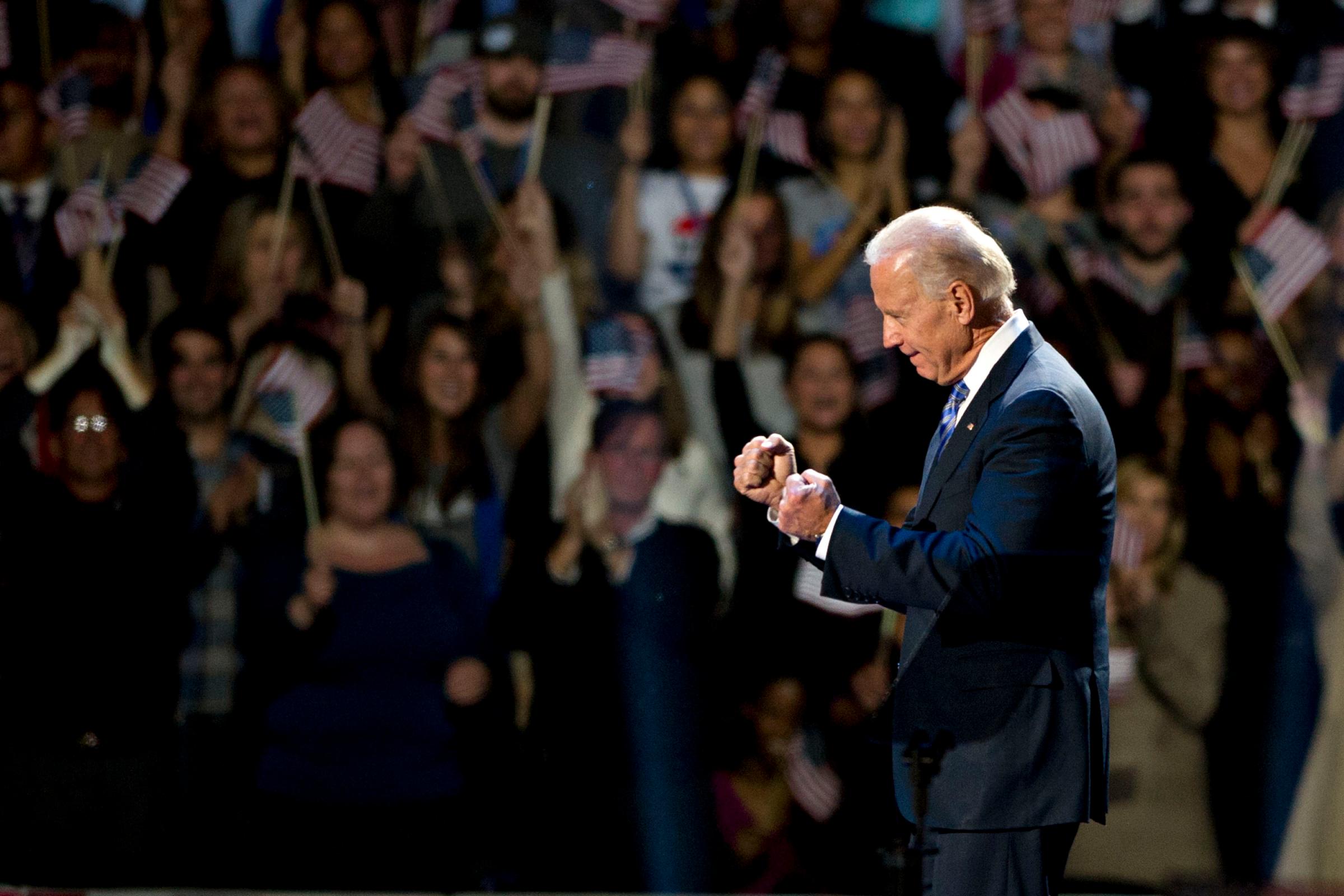

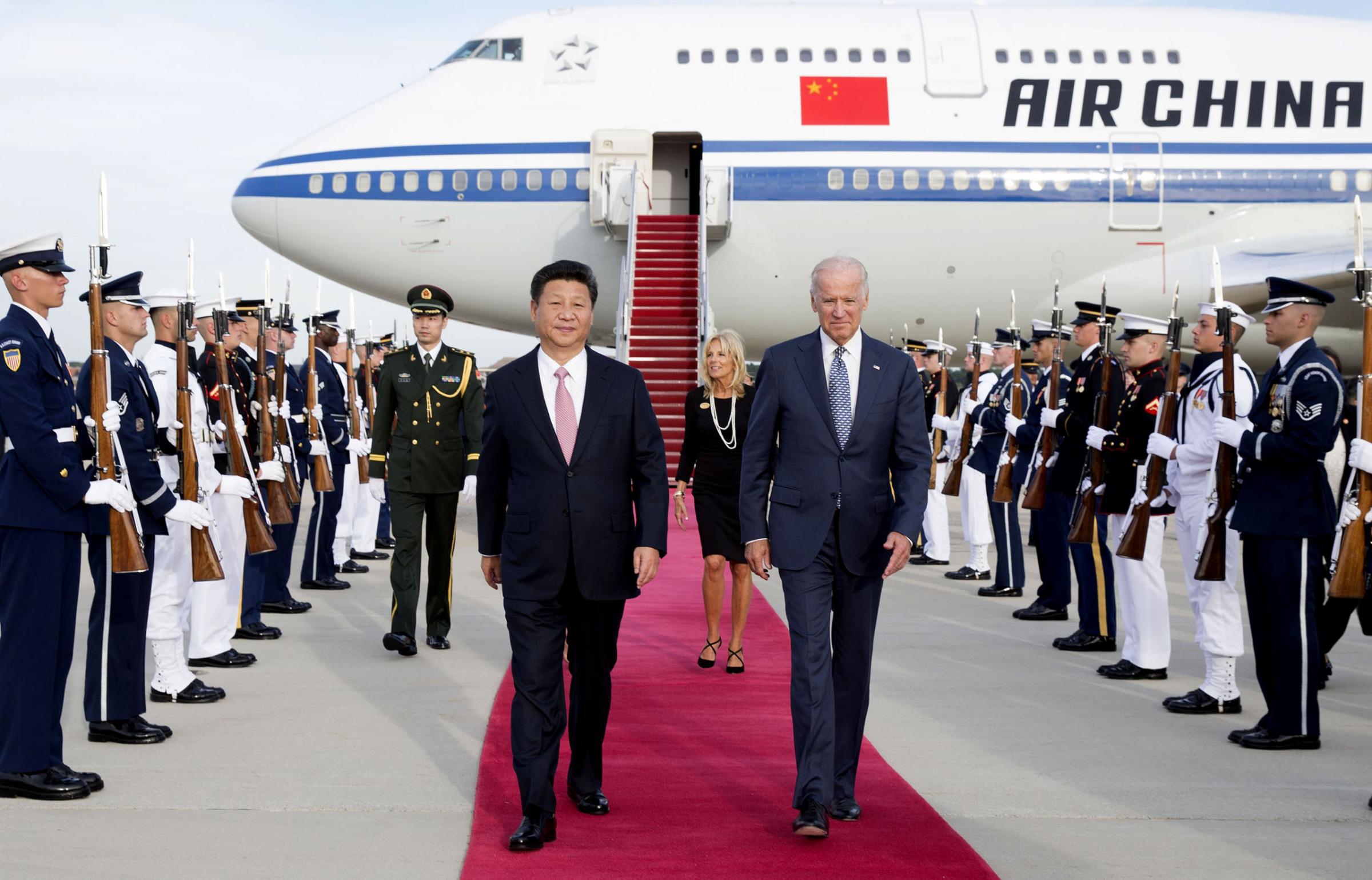

See Joe Biden’s Career in Pictures

Throughout his public hedging and personal conversations, Biden continued to ask his closest advisers if they thought he stood a chance at winning the nomination. The road ahead would be rough, they told him, and cautioned him that the kid gloves he enjoyed as a beloved Vice President would not continue should he make a play for the Presidency. His approach would suddenly be scrutinized, and every word he has uttered during the last seven years as Vice President subjected to another look, they warned him. Did he really want to subject himself—and his still-mourning family—to that for a campaign and, perhaps, eight years as President?

Biden saw his potential and peril in public polling. Yes, he was personally popular, his aides cautioned, but those favorable views would likely sink should he become a candidate. Remember Clinton’s polling numbers when she left her job as an apolitical Secretary of State, they urged him. Those numbers sank as she re-entered politics and was no longer a diplomat. And liking someone wasn’t the same as wanting to vote for someone.

For the first time in a generation, a sitting Vice President would enter the Presidential race as an underdog to succeed his boss, some 27 points behind Hillary Clinton in the a CNN poll released Oct. 19, with a plurality of his own party—38% to 30% in the same poll—saying that he should just retire. He has scant campaign money, an almost no campaign apparatus.

In the end, Biden came to the same conclusion. He still has the drive to be President; it’s hard to snuff that desire. But this was simply not the time, he concluded. He spoke frankly about lacking the “emotional fuel” for a run during conversations with allies, and it never materialized, no matter how much he wanted to honor a final request from his late son.

“Beau is our inspiration,” the Vice President said. But he wasn’t enough to sustain a long and likely brutal campaign.

The Vice President, whose first wife and daughter died in a car crash in 1972, is exceptionally close with his family. He counted on his son Beau, the 46-year-old former Attorney General of Delaware, as a top political adviser. Before his death, Beau urged his “pop,” as he called him, to promise he would run for the White House in 2016. Biden resisted making the promise, but asked his closest advisers to investigate what it would take to make that happen.

Then, Beau died. His death hit the Biden clan exceptionally hard, and Biden largely disappeared from the White House and his suite of offices next door at the former War Department temple during the summer.

As the Bidens retreated to South Carolina, a favorite refuge, word of Beau’s request found its way into a New York Times column, and talk of a presidential run started getting more serious. Clinton backers—and those who were cheering on Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders as an alternative to the former First Lady—were watching Biden’s deliberations trying to figure out his plans.

“If I were to announce to run, I have to be able to commit to all of you that I would be able to give it my whole heart and my whole soul,” Biden told members of the Democratic National Committee. “And right now, both are pretty well banged up.”

But at another event, in Pittsburgh, Biden trotted through a Labor Day parade as though he were already running. In the crowd, supporters chanted, “Run, Joe, Run.”

In the end, though, Biden thought better of it. As he painfully confided to “The Late Show” host Stephen Colbert—and the nation watching on television—he was hardly at his fighting best.

“I don’t think any man or woman should run for president, unless number one they know exactly why they would want to be President,” Biden said. “And, two, they can look at the folks out there and say, ‘I promise you (that) you have my whole heart, my whole soul, my energy and my passion to do this.’ And I’d be lying if I said I knew I was there.”

In the end, he was not.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com