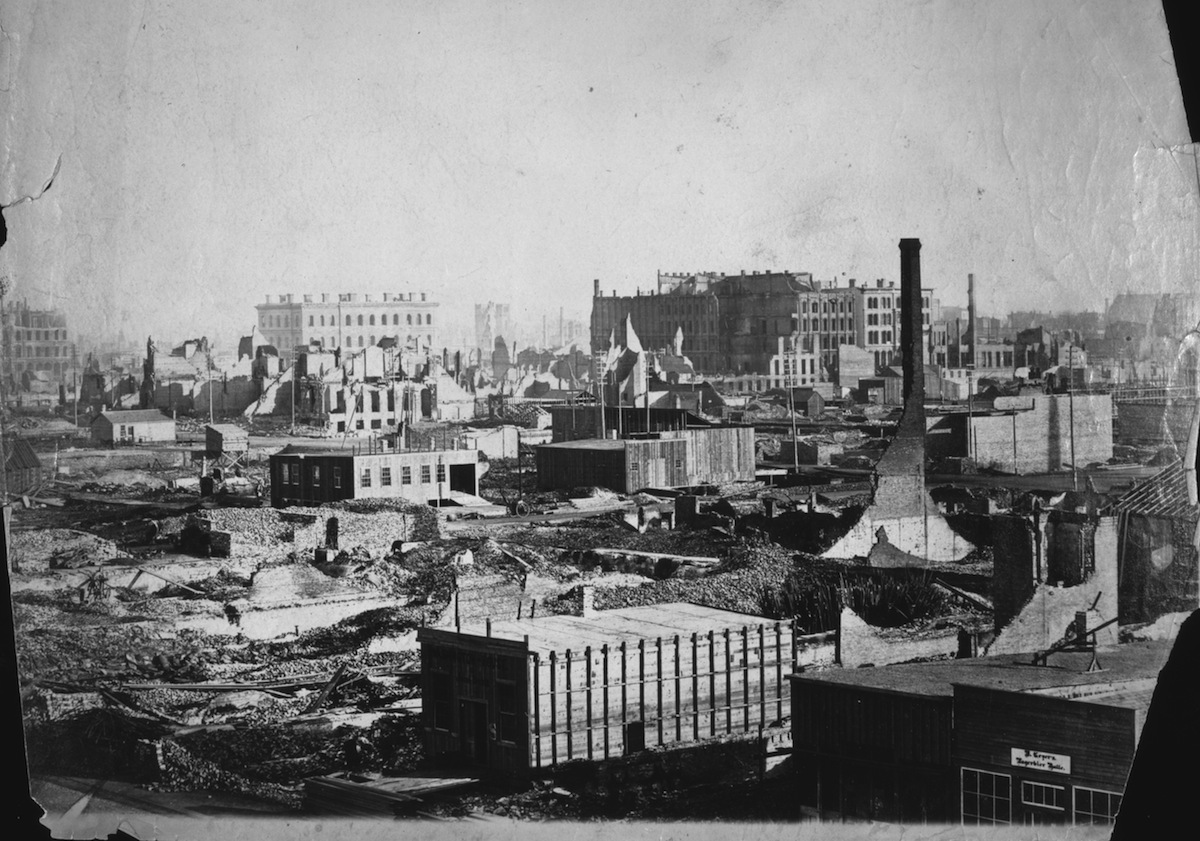

Without a doubt, the Great Chicago Fire was one of the worst disasters of the 19th century. It leveled more than 3 square miles of the city, killing 300 people and leaving another 100,000 homeless. But for nearly a century and a half, questions have lingered over who—or what—actually started the fire on this day, Oct. 8, in 1871. The debate has featured a rotating cast of colorful (possible) culprits, but every explanation has its doubters. To this day, no one knows for sure which, if any, is to blame. The suspects include:

Mrs. O’Leary and her cow. That the fire started in the barn behind Catherine O’Leary’s West Side cottage is certain. How it started is the question, although throughout her life, O’Leary suffered the condemnation of a city that blamed her for it. As the popular story went, O’Leary was in the barn around 9 p.m., milking her cow, when the cow kicked over a lantern and sparked the inferno. According to the Chicago Tribune, O’Leary herself consistently denied this account, saying that she never milked after dark. However, as an Irish immigrant living in poverty, she made a convenient scapegoat—and reporters seized on the fire’s great irony: Although it decimated Chicago’s downtown, wiping out the central business district and charring the courthouse, the blaze that began in her barn somehow spared O’Leary’s meager cottage.

Peg Leg Sullivan. A century after the fire, officials turned their attention to a different suspect (although the cow still played a supporting role). As TIME reported in 1971, this alternate account featured Mrs. O’Leary’s one-legged neighbor, who was allegedly having a nightcap in the barn when a spark from his pipe ignited the hay. “As he tried to flee, his peg leg stuck in a floor crack,” TIME recounts. “He discarded it and hobbled to safety by clinging to the cow.” An amateur historian, Richard Bales, found enough evidence pointing to Daniel “Peg Leg” Sullivan—including inconsistencies in Sullivan’s story about what happened that night—that a Chicago City Council committee officially exonerated O’Leary in 1997.

A comet. Some have suggested that pieces of Biela’s Comet—a periodic comet that apparently disintegrated around the time of the fire—might have fallen to Earth and sparked not only the Chicago fire but other devastating blazes in Wisconsin and Michigan that same year. Bales debunks this theory in his book, The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow, arguing that the blue flames some firemen reported seeing were likely from burning natural gas, not extraterrestrial gases, as theorized by the comet camp.

A gambler. A more likely culprit, according to the Chicago Tribune, is the one person who actually admitted fault for the blaze: a businessman and gambler named Louis Cohn. Cohn, who died in 1942, was 18 when the fire broke out. His will contained a public confession he’d previously only shared with friends and family: He and Mrs. O’Leary’s son, along with a few other boys, had been shooting craps in the hayloft by lantern light that night, when one of the boys—not the cow—knocked the lantern over. Cohn’s story is perhaps the most believable of the bunch, since he had nothing to gain from lying. In fact, his version of the story is anything but self-aggrandizing. A 1944 press release from the Medill School of Journalism, which received an endowment from Cohn’s estate, notes, “Mr. Cohn never denied that when the other boys fled, he stopped long enough to scoop up the money.”

Read about the centennial commemoration of the fire, in 1971, here in the TIME archives: Commemorative Fireworks

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Catches Fire (Mar. 25, 1911)

By Michele Anderson

The Triangle Shirtwaist Company’s fire resulted in the tragic loss of nearly 150 young women and girls on March 25, 1911, in New York City. The garment workers at the company had been attempting to unionize to gain better wages and improved working conditions. The factory’s management responded by locking the workers into the building. Fabric scraps, oil and hot machines crammed into rooms on the upper floors of the ten-story building quickly unleashed an inferno within the building. With the exits blocked, girls attempted to use the rusted fire escape or jump from windows into the fire department’s dry-rotted nets, only to plunge onto the pavement in front of bystanders below. The tragedy was exasperated by the failure of the U.S. government to protect its citizens who were working in deplorable conditions, but it was difficult for anyone who saw the corpses lined up on sidewalks waiting for identification to deny the need for labor reform and improved fire safety equipment. The deaths unified female labor reformers of the Progressive era.

Michele Anderson, a teacher at John Glenn High School near Detroit, was named 2014 National History Teacher of the Year by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History and HISTORY.

Read more about the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire here in the TIME Vault

The Great Migration Begins (1915)

By Isabel Wilkerson

In today’s world African Americans are viewed as urban people, but that’s a very new phenomenon: The vast majority of time that African Americans have been on this continent, they’ve been primarily Southern and rural. That changed with the Great Migration, a mass relocation of 6 million African Americans from the Jim Crow South to the North and West, starting in 1915.

This leaderless revolution, a response to oppression in the South, was set in motion by the labor shortage in the North during World War I. And once the door opened, a flood of people came. Those who migrated became the advance guard of the Civil Rights movement; they shaped our culture, from music to sports. On the other hand, one of the responses to their presence was fear and hostility. In these big cities that they had hoped would be refuges, they were still blocked from the American dream. The Great Migration was a watershed demographic change in our country’s history—and we’re still living with its effects today. (As told to Lily Rothman)

Isabel Wilkerson is the Pulitzer-Prize-winning writer of The Warmth of Other Suns, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Lynton History Prize from Harvard and Columbia universities and the Stephen Ambrose Oral History Prize, among other honors. The book is currently being developed into a TV adaption to be executive produced by Shonda Rhimes.

Read more about the Great Migration here in the TIME Vault

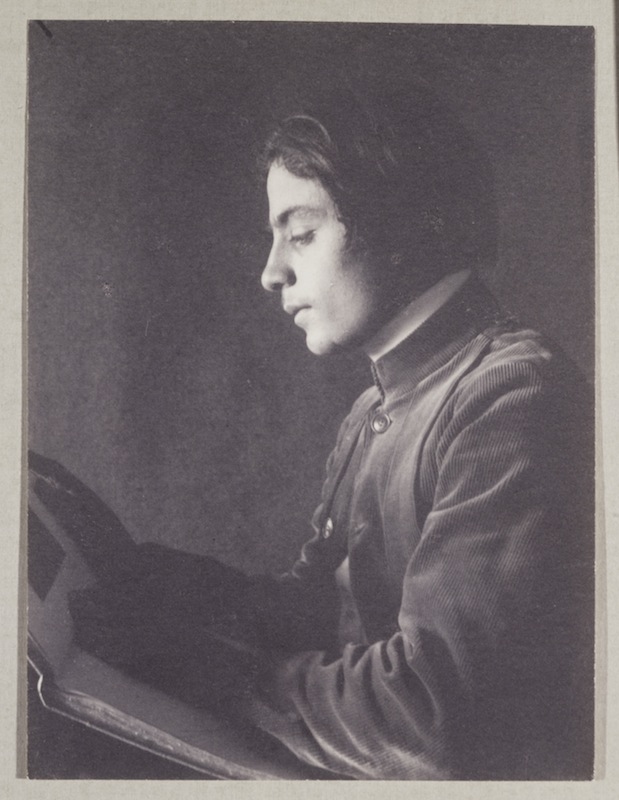

The Prophet Is Published (Sept. 23, 1923)

By Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen

In the aftermath of World War I, the Lebanese-born, Boston-based poet-philosopher Kahlil Gibran wrote what would become one of the world’s most translated works of philosophy: The Prophet. This collection of inspirational sermons delivered by a fictional prophet—on love, marriage, work, reason, self-knowledge and ethics—challenged tired orthodoxies and oppressive ideologies. Though Gibran’s exaltation of human individuality, creativity and difference was not entirely original, the book’s success lay in his ability to make his insights feel like revelations. Ever since its publication in 1923, The Prophet has been a salve for readers who tried—in good American fashion—to break from conformity. Gibran readers include Woodrow Wilson and American soldiers during World War II (thanks to its selection for the American Services Editions in 1943); Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash; members of the 1960s counterculture and now Salma Hayek. The Prophet taught self-trust amid the buzzing, blooming confusion of modern America. Sometimes it takes a foreigner to speak the voice of Americans’ inner conscience.

Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen is the Merle Curti Associate Professor of History and the founder of the Intellectual History Group at University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her book, American Nietzsche: A History of an Icon and His Ideas, won the John H. Dunning Prize, an award for an outstanding monograph in a subject in U.S. history, from the American Historical Association.

Read more about the ongoing influence of The Prophet, here in the TIME Vault

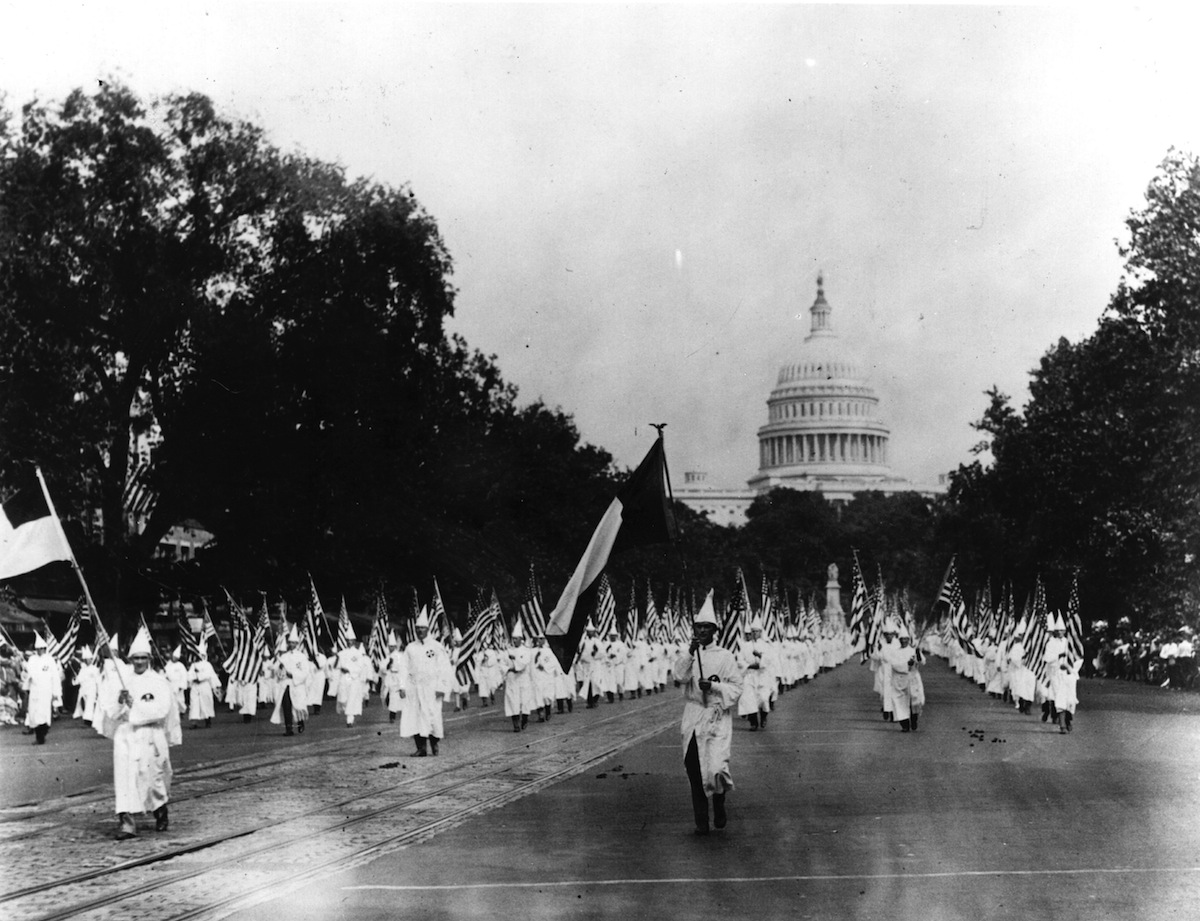

The KKK Marches in Washington (Aug. 8, 1925)

By James Loewen

When the KKK paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., the headline in the New York Times declared “Sight Astonishes Capital: Robed, but Unmasked Hosts in White Move Along Avenue.” The marchers, the article noted, received “a warm reception.” The parade took place in broad daylight, in the nation’s capital, and most of the participants were from the north. This event symbolizes the Nadir of Race Relations, a terrible era from 1890 to about 1940, when race relations grew worse and worse. During this period white Americans became more racist than at any other point in our history, even during slavery. Also during the Nadir, the phenomenon of sundown towns swept the North. These are towns that were for decades—and in some cases still are—all-white on purpose.

Among the other terrible legacies of that period are its inaccurate white supremacist histories of everything from Christopher Columbus and U.S. Grant to Woodrow Wilson, and the astounding gap between black and white media family wealth— problems that we are still trying to transcend.

James Loewen is professor emeritus at the University of Vermont and the best-selling author of Lies My Teacher Told Me. He has received the Spirit of America Award from the National Council for the Social Studies and was the first white recipient of the American Sociological Association’s Cox-Johnson-Frazier Award for scholarship in service to social justice.

Read original 1925 coverage of the parade, here in the TIME Vault

Thomas Dorsey Invents the Gospel Blues (1932)

By Jon Butler

In Chicago in 1932, an African American composer named Thomas A. Dorsey, who had been a nightclub jazz pianist, wrote a song inspired by his wife’s death in childbirth. The song, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” unexpectedly became the foundation for the modern African American gospel music tradition. Its success stimulated an entirely new music industry—the gospel blues. It became a touchstone for the dramatic role that music played in sustaining and forwarding America’s Civil Rights movement; Martin Luther King Jr. often asked supporters to sing it before they marched, including the night before his assassination. The gospel blues also brought singers such as Mahalia Jackson, Sister Rosetta Tharp, and the Golden Gate Quartet to prominence and was later foundational for Aretha Franklin and Whitney Houston, among many others. That tiny, inauspicious moment in 1932 created a subtle yet profound change in American life, ultimately producing musical anthems of powerful personal, moral, and political transformation.

Jon Butler is Howard R. Lamar Emeritus Professor of American Studies, History & Religious Studies at Yale University, and the current president of the Organization of American Historians.

Harry Hopkins Starts Work (May 22, 1933)

By Linda Gordon

About two months after he took office, Franklin Roosevelt appointed a former social worker to head an emergency program of aid to the unemployed. The moment Harry Hopkins started work, on May 22, 1933 —before he even had an office—he dragged a desk into the hall of the building where he was located and immediately began sending out money. Some critics disapproved of his haste and wanted longer consideration of this federal expenditure. Hopkins responded, famously, “People don’t eat in the long run; they eat every day.” In two hours he spent $5 million dollars, the equivalent of about $70 million today. In addition to putting money into the hands of consumers, it was also a tremendous confidence-raising gesture that said, ‘This administration is not going to allow our economy to go completely under.’ Emergency relief was the most popular of the New Deal programs and has been called a major step in saving capitalism. It inaugurated a pattern of government action in crises that would otherwise spin out of control. (As told to Lily Rothman)

Linda Gordon is a professor of history at New York University and a two-time winner of the Bancroft prize for the best book in U.S. history.

Read a 1934 cover story about Harry Hopkins and his work, here in the TIME Vault

FDR Accepts the 1936 Democratic Presidential Nomination (June 27, 1936)

By Jefferson Cowie

The “political equality we once had won,” FDR boomed as he accepted the Democratic nomination for a second presidential term in 1936, had been rendered “meaningless in the face of economic inequality.” The government no longer belonged to the people but had been taken hostage by “privileged princes of these new economic dynasties, thirsty for power.” Deep in the Great Depression, Roosevelt promised that his New Deal would recalibrate the balance of power between the people and the “economic royalists.” It was some of the most extraordinary—and fleeting—rhetoric in American presidential history. Yet as a result, working people flocked to the Democratic Party, fostering not only an electoral landslide but also a political coalition that governed the nation for decades to come.

Jefferson Cowie teaches at Cornell University. His book Stayin’ Alive: The 1970’s and the Last Days of the Working Class received the Parkman Prize for the Best Book in American History. His forthcoming book is The Great Exception: The New Deal and the Limits of American Politics.

Read original 1936 coverage of Roosevelt’s decision, here in the TIME Vault

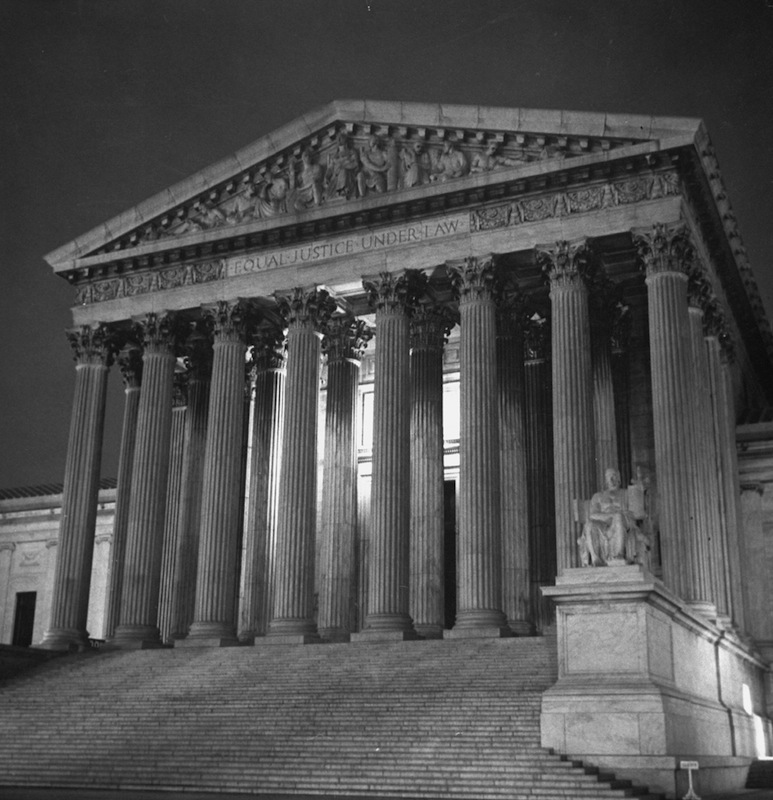

Hugo Black Is Appointed to the Supreme Court (Aug. 19, 1937)

By Akhil Reed Amar

Hugo L. Black of Alabama, FDR’s first appointment to the Supreme Court, defined the American judicial scene for three and a half decades. Black first defined and then implemented a reformist agenda that would revolutionize modern American constitutional law. For his first 15 years, Black set the table with new ideas—often presented in dissent, at first. In his last two decades on the Court, Black would watch his reformist agenda become the supreme law of the land, moving from dissenting opinions to majority opinions on issues of voting rights, speech rights, religious rights, criminal procedure rights and the Bill of Rights more generally.

Akhil Reed Amar is Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science at Yale University, and the author of several books about the Constitution and its history. His latest book, The Law of the Land, was released in April.

Read 1937 coverage of Black’s confirmation, here in the TIME Vault

Truman Replaces Wallace (July 21, 1944)

By William Chafe

The Cold War seems inevitable, but few things are. Rather, that road diverged in July of 1944, when Harry S. Truman took the place of incumbent vice-president Henry Wallace on the Democratic ticket.

After World War II, President Roosevelt had a secret plan for how he would work things out with Stalin, but he died before sharing it. Truman entered the White House with almost no experience in foreign policy. The State Department told him that action must be taken on the Russian threat. The result was the Truman Doctrine: good against evil, communism against democracy, the Cold War.

Meanwhile, Wallace — named Secretary of Commerce by FDR after the election — became the leading voice of progressive politics in the Cabinet. He thought there was a way of working out an agreement with the USSR. When he made a speech to that effect, Truman dismissed him from the Cabinet. What a different world there might have been if Wallace, not Truman, occupied the position of Vice-President when Franklin Roosevelt died.

William Chafe is professor emeritus of history at Duke University, author of The Unfinished Journey: America Since 1945 (8th edition), and a past president of the Organization of American Historians.

Read 1944 coverage of Truman’s nomination, here in the TIME Vault

The North Atlantic Treaty Is Signed (April 4, 1949)

By Richard Stewart

The signing of the North Atlantic Treaty meant that, after intervening twice in the previous 32 years to restore peace in Europe, the U.S. was finally committed to an international alliance in peacetime, focused on preventing war in the first place. That act shaped our foreign policy, politics, military spending, military structure, doctrine, equipment and military ethos for the years to come. It had a remarkable and salutary effect on helping to bring a shattered Europe together as a group of free and democratic states. Today it is our continuing commitment to NATO that prevents any further spillover of conflict as the Russian bear sharpens his claws, again, this time on Ukraine. NATO was created because of the wars of the 20th century, but it has kept the peace in Europe for longer than any time in the previous several centuries.

Richard W. Stewart is acting director at the Center of Military History in Washington, D.C., and chief historian of the U.S. Army. He is also president of the U.S. Commission on Military History, the U.S. arm of the International Commission on Military History. (These remarks are his own opinion, not the views of the U.S. Army, Department of Defense or the United States Government.)

Read 1949 coverage of the signing of the treaty, here in the TIME Vault

Barbara Johns Walks Out (April 23, 1951)

By Clayborne Carson

On April 23, 1951, sixteen-year-old Barbara Johns led a walkout by four hundred black students to protest inadequate facilities at segregated Robert R. Moton High School in Farmville, Virginia. Vowing to boycott classes until the local all-white School Board addressed their complaints, Johns and another student wrote to an NAACP attorney, who agreed to file a lawsuit seeking desegregation instead of just improved facilities. This suit was eventually consolidated with four similar cases including Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. Johns never became famous, but her protest prompted the Supreme Court’s historic 1954 decision outlawing public school segregation.

Clayborne Carson is Martin Luther King, Jr., Centennial Professor and founding director of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute at Stanford University.

Read more about school desegregation and the Brown case, here in the TIME Vault

Emmett Till Is Murdered (Aug. 28, 1955)

By Jacqueline Jones

In September of 1955, Mose Wright took the witness stand in a Mississippi courtroom. Rising from his chair, he pointed a finger at one of the two men who had murdered his niece’s son, Emmett Till. “There he is,” said Wright, in an extraordinary act of personal courage. Till’s killers were not convicted in 1955, but Till—a teenager who his killers thought had flirted with a white woman—still changed the country. In Chicago, Till’s mother, Mamie Bradley Till, insisted on an open casket at her son’s funeral: She said she “wanted the world to see” her son’s mutilated corpse, battered beyond recognition. Magazines and newspapers ran the photo, signaling the power of shocking images as a new weapon in the generations-long struggle for black rights.

Jacqueline Jones is chair of the History department at the University of Texas at Austin and a two-time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in history.

Read 1955 coverage of the trial, here in the TIME Vault

The Birth Control Pill Is Approved (May 9, 1960)

By Annette Gordon-Reed

The birth control pill was one of the most significant achievements of the 20th century. Contraception wasn’t new: From ancient times, women have used methods of varying degrees of reliability to prevent getting pregnant. But the Pill, which was much more effective, transformed society. Americans began to think differently about sex, contraception and about women’s capacity to control their own bodies and participate as truly equal members of society. Sex uncoupled from procreation, the freedom to choose when and if to become a mother, the ability for a woman to plan her life without fear of an unwanted pregnancy getting in the way—these opened the door for the liberation of women.

Annette Gordon-Reed is Charles Warren Professor of American Legal History at Harvard Law School, a Professor of History at Harvard University, Carol K. Pforzheimer Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and a winner of the Pulitzer Prize in history.

Read TIME’s 1967 cover story about the Pill, here in the TIME Vault

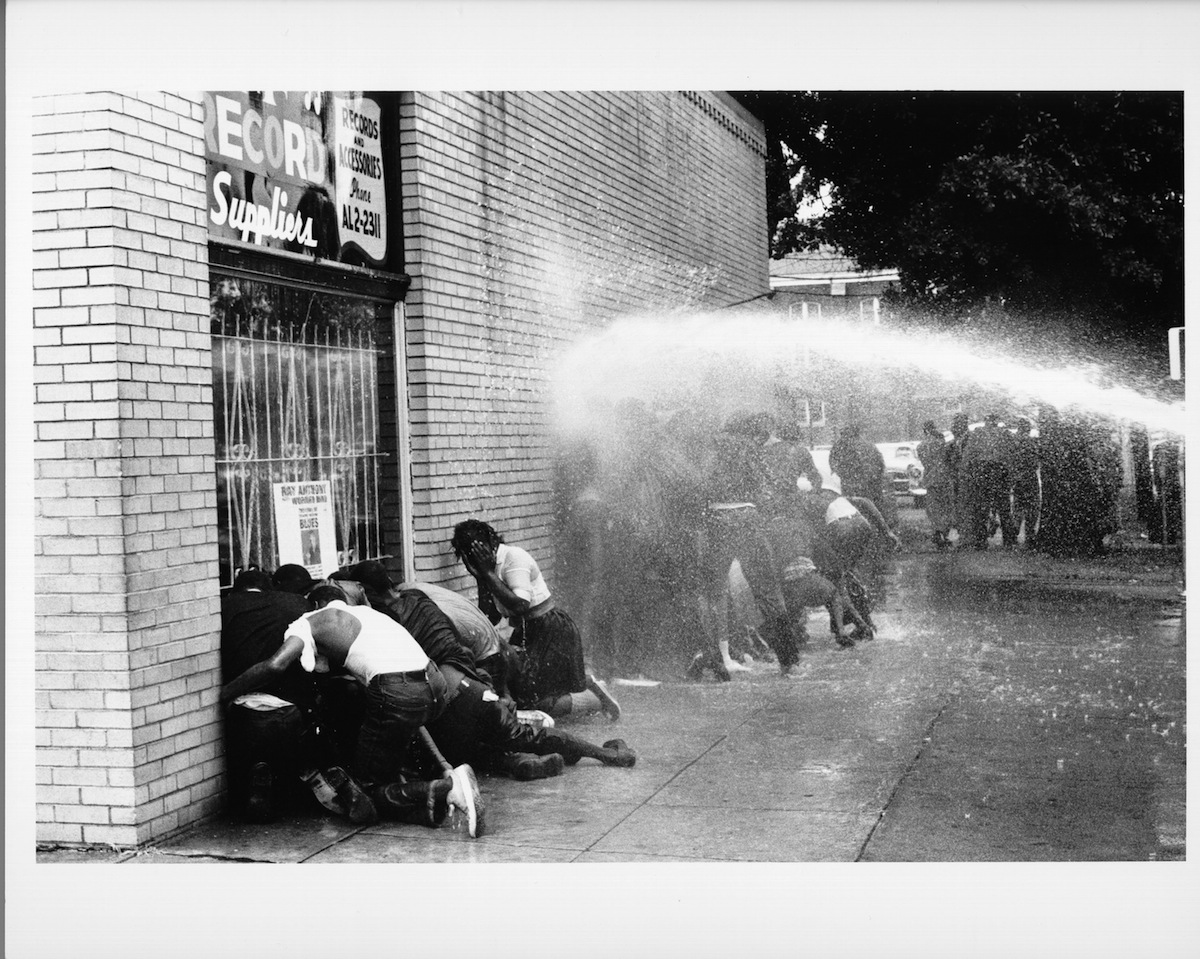

The Children March in Birmingham (May 2, 1963)

By Taylor Branch

The civil rights breakthrough in the 1960s required galvanizing the whole country, not just through rational arguments but by really breaking down people’s emotional resistance and making citizens across the country see they needed to do something. The children’s march really was the single event most responsible for inducing faraway people in Montana and Maine to say, “I need to do something about this.” Demonstrations spread like wildfire all across the country. It led to the March on Washington and it really pushed President Kennedy to propose what became the Civil Rights Act basically a month after those demonstrations.

I myself distinctly and vividly remember seeing those pictures and how deeply it affected me. I was thinking, ‘Gosh, when I get old and responsible maybe I’d do something about civil rights,’—and the next thing I know I see these little kids marching right through fire hoses. It’s a big emotional turning point that’s still not widely analyzed, in part because it’s embarrassing to adults to say that it took these pictures to make us finally do something. (As told to Lily Rothman)

Taylor Branch is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of the America in the King Years books.

Read 1963 coverage of the march, here in the TIME Vault

Thich Quang Duc’s Self-Immolation Is Broadcast (June 11, 1963)

By Mary Frances Berry

The international newspaper and TV coverage of Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức burning himself to death during a demonstration in Saigon changed the course of the Vietnam War and of American life. In the immediate aftermath, it caused horror and a reassessment of policy, which eventually led to more American troops on the ground and in the air but also to more media coverage in which Americans could actually see the war. It encouraged draft dodging and antiwar protests, some of which led to violence. Its effects have been residual as well. It sparked a so-far-permanent distrust of our government, which said we were winning the war when the media showed we were actually not. It caused polarization in our society between those who thought we should support the war and those who didn’t. In addition, the War on Poverty was interrupted because funds went to supporting the war, and it has never been restarted.

Mary Frances Berry is Geraldine R. Segal Professor of American Social Thought and Professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania. She has also served as a member and as chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, and as the United States’ Assistant Secretary for Education. She is a past president of the Organization of American Historians and a fellow of the Society of American Historians.

Read 1963 coverage of the self-immolation, here in the TIME Vault

Howard Smith Amends the Civil Rights Act (Feb. 8, 1964)

By Stephanie Coontz

By 1964, little headway had been made in the women’s movement since winning the vote in 1920. So women’s rights supporters were delighted that year when Representative Howard Smith of Virginia offered a one-word amendment to Civil Rights Act, adding sex to the list of forms of discrimination prohibited by the act. Smith, a segregationist, opposed the bill—but he argued that if it passed, white women should get the same protections being extended to black men and women.

Many legislators hoped, and others feared, that adding gender equality would kill the entire bill. Even after its passage, the director of the newly-formed Equal Employment Opportunity Commission refused to enforce the sex clause, calling it “a fluke…conceived out of wedlock.”

Women’s fury at that refusal jump-started a wave of legal and political activism that forever changed the roles of women (and men) at work and at home.

Stephanie Coontz teaches at The Evergreen State College in Olympia Washington and is Director of Research at the Council on Contemporary Families. Recent books include Marriage, a History: How Love Conquered Marriage and A Strange Stirring: The Feminine Mystique and American Women at the Dawn of the 1960s.

Read more about the inclusion of sex in the Civil Rights Bill, from 1964, here in the TIME Vault

Ronald Reagan Speaks to Conservatives (Oct. 27, 1964)

By H.W. Brands

Barry Goldwater’s campaign was floundering a week before the 1964 election. The candidate inspired none but the truest of believers; the Republican regulars were dejectedly heading for the exits. In a desperate effort to energize donors, the campaign put a political unknown on television—and Ronald Reagan proceeded to electrify the country. His 30-minute address, labeled “A Time for Choosing,” transformed the washed-up actor into the darling of conservatives and launched a political career that would carry Reagan to White House, revive American conservatism and push Soviet communism to the brink of dissolution.

H.W. Brands holds the Jack S. Blanton Sr. Chair in History at the University of Texas at Austin, and is the author of two Pulitzer-finalist works of history. He is also currently writing, on Twitter, the history of the United States in haiku.

Read coverage of Reagan’s roll in the 1964 elections, here in the TIME Vault

The Immigration and Nationality Act Is Signed (Oct. 3, 1965)

By Vicki Ruiz

In a dramatic ceremony at the Statue of Liberty, President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, catalyzing an increase in cultural diversity in the United States. In the wake of the civil rights movement, the old restrictive quotas from the 1920s, which favored northern Europeans over southern Europeans, struck many Americans as anachronistic. President John F. Kennedy called this quota system “intolerable.” The 1965 act was meant to promote family unification, level the field for lawful entry and ease the way for foreign-born professionals. Fifty years later, its impact can be seen at all levels of society. Today over 40 million foreign-born individuals live in the United States, about three-quarters of whom have legal status. They and their American-born children comprise nearly 25% of the U.S. population. “The lady with the light”—to quote one Cambodian refugee—continues to burn bright.

Vicki L. Ruiz is Distinguished Professor of History and Chicano/Latino Studies at the University of California, Irvine, and the author of Cannery Women, Cannery Lives and From Out of the Shadows: Mexican Women in Twentieth- Century America. A fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, she is currently president of the American Historical Association.

Read 1965 coverage of the lifting of the quotas, here in the TIME Vault

Alcatraz Is Occupied (Nov. 20, 1969)

By Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

While organizing for self-determination within Native Americans communities and nations had proceeded throughout the 1960s, few in the general public were aware until the November 1969 seizure and 18-month occupation of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. The occupation grabbed world-wide media attention. An alliance known as Indians of All Tribes was initiated by Native American students and relocated Natives living in the Bay Area. They built a thriving village on the island, which drew Indigenous pilgrimages from all over the continent and radicalized thousands, especially the youth. Treaties, self-determination, and land restitution returned to the national agenda, as the occupiers demanded implementation of international law. Negotiations ended the occupation when the Nixon administration agreed to amnesty for those involved.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz is author of An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States.

Read original coverage of the occupation, here in the TIME Vault

Affirmative Action Goes Unchallenged (Oct. 12, 1971)

By Khalil Gibran Muhammad

For much of the 20th century, unions, private employers and government agencies affirmatively discriminated based on race—until, through workplace protests, public demonstrations and political negotiation, African Americans compelled Congress and President Richard Nixon to adopt affirmative action policies. In the late 1960s, the “Philadelphia Plan,” inspired by a set of local initiatives in that city, set federal hiring benchmarks for proportional representation of African Americans in many skilled and white-collar jobs generated by government contracts. Though the idea was challenged, in 1971 the Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal, thus allowing the policy to stand and encouraging the growth of affirmative action.

Every sphere of American life transformed as a result. From college classrooms to corporate boardrooms, African Americans entered the middle-class in record numbers. White women and immigrants of color from around the globe also moved from the margins to the center of U.S. corporate culture. And the immediate and lasting impact of affirmative action has fueled nearly 40 years of conservative opposition and cries of “reverse discrimination” which remain at the heart of American political culture today.

Khalil Gibran Muhammad is director of the Schomburg Center For Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library. He previously taught history at Indiana University and was an associate editor at the Journal of American History.

Read 1970 coverage of the birth of the Philadelphia Plan, here in the TIME Vault

California Passes Proposition 13 (June 6, 1978)

![Mark Slade [Misc.] Mark Slade [Misc.]](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/prop13.jpeg?quality=75&w=2400)

By Lizabeth Cohen

In June of 1978 the voters of California overwhelmingly passed Proposition 13, limiting local property taxes and making it harder for communities to raise them in the future. This 20th-century tax revolt opened the floodgates to other anti-tax ballot measures at the state level and initiated a general shift in popular opinion. This anti-tax reorientation has decreased the amount and quality of public services; led to increases in alternative, regressive sources of taxation such as the sales tax; and encouraged new kinds of inequalities such as between old and new homeowners, between residents able to afford privatized services and those not, and between communities with other sources of revenue to support schools and services and those without. On a broader scale, Proposition 13 represented a new unwillingness to view government as a provider of positive benefits to all members of a community and an embrace of more consumerist and individualized ways of securing services.

Lizabeth Cohen is dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and Howard Mumford Jones Professor of American Studies at Harvard University.

Read 1978 coverage of Proposition 13, here in the TIME Vault

The Embassy in Tehran Is Occupied (Nov. 4, 1979)

By Tony Horwitz

The takeover of the U.S. embassy in Tehran set us down the track we’re still on in the Middle East. Iranian militants held Americans hostage for 444 days while decrying the U.S. and demanding the return of the Shah and his riches. The crisis cemented Iran, a former ally, as our greatest foe in the region. It bound us more closely to Saudi Arabia and other Sunni regimes. It led us to build up Saddam Hussein’s power as a bulwark against Iran—and we know how that turned out. Thirty-six years after the takeover, Americans still regard Iranians as treacherous and cast Shi’ites in general as extremists. U.S. impotence during the hostage crisis—including a disastrous rescue attempt—also helped sink Jimmy Carter in the 1980 election. There’s an intriguing what-if: had events played out differently in Iran, we might not have had Ronald Reagan as president.

Tony Horwitz is a winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the William Henry Seward Award for Excellence in Civil War Biography. He is currently the vice president of the Society of American Historians.

Read more about embassy takeover, as described in 1979, here in the TIME Vault

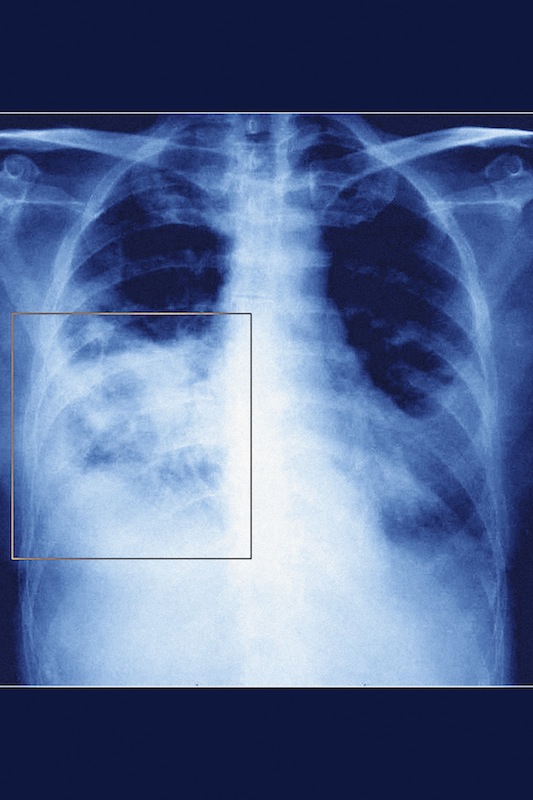

The Pneumocystis Pneumonia Report (June 5, 1981)

By Elizabeth Fenn

June 5, 1981. That’s the date that the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) published an article titled “Pneumocystis Pneumonia–Los Angeles.” This succinct, two-page essay turned out to be the first published account of the AIDS epidemic. It described Pneumocystis carinii, a rare protozoan infection that exploits weak immune systems, as it had developed in five gay men. The years that followed brought untold suffering. But AIDS also ushered in a revolution in attitudes that has allowed us to talk about sexuality more frankly than ever before. In the end, ironically, this helped open the door to gay marriage.

Elizabeth Fenn is department chair and associate professor of history at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her book Encounters at the Heart of the World was awarded the 2015 Pulitzer Prize in History.

Read 1981 coverage of the mysterious disease, here in the TIME Vault

The Americans With Disabilities Act Is Signed (July 26, 1990)

By Akira Iriye

The Americans With Disabilities Act formally recognized the fact that people who are disabled, physically as well as mentally, are part of society. Toward the end of the 20th century, the United States came face to face with the fact these people cannot simply be ignored. This is a very personal observation, because we have a daughter who was born with some brain damage. Just as racial desegregation was important, it’s important that people with handicaps be recognized as full-fledged members of society. It’s a progression toward recognizing all people of all categories. The idea that some people are different, we are much more tolerant about that, and that’s one of the most major achievements of the 20th century. (As told to Lily Rothman)

Akira Iriye, a historian with interest in global, transnational affairs, is Charles Warren Research Professor of American History at Harvard.

Read 1990 coverage of the ADA, here in the TIME Vault

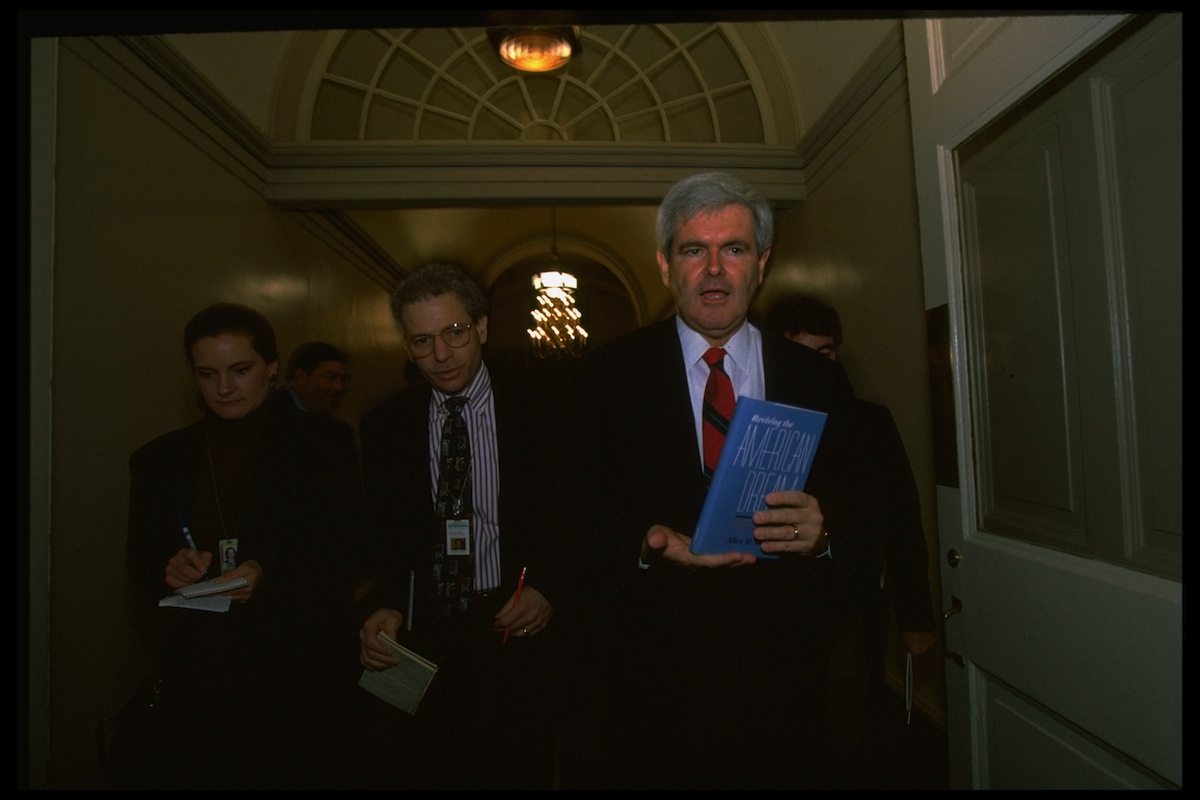

The 1994 Midterm Elections Go to the Republicans (Nov. 8, 1994)

By Julian Zelizer

In the 1994 midterm elections, Republicans—led by Newt Gingrich—took control of Congress for the first time since 1954. Gingrich and his allies ran a masterful campaign that revolved around “The Contract with America,” ten promises that the GOP vowed to enact if they took power. Their victory opened up the Republican Party to more conservative elements, and shaped the generations of Republicans who have dominated Capitol Hill since that time, even during the period of Democratic control. But the outcome of that election was not just important in terms of who controlled the majority of Congress, but also because it launched an era when conservatism would make the legislative branch, rather than the White House, the base of their power. Through legislative control and partisan tactics that had once been considered impermissible, the post-1994 congressional Republicans made it much more difficult for liberal ideas to succeed in the United States.

Julian Zelizer, a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University, is the author and editor of numerous books on American political history. His most recent book is The Fierce Urgency of Now: Lyndon Johnson, Congress, and the Battle for the Great Society.

Read a 1994 cover story about the election results, here in the TIME Vault

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com