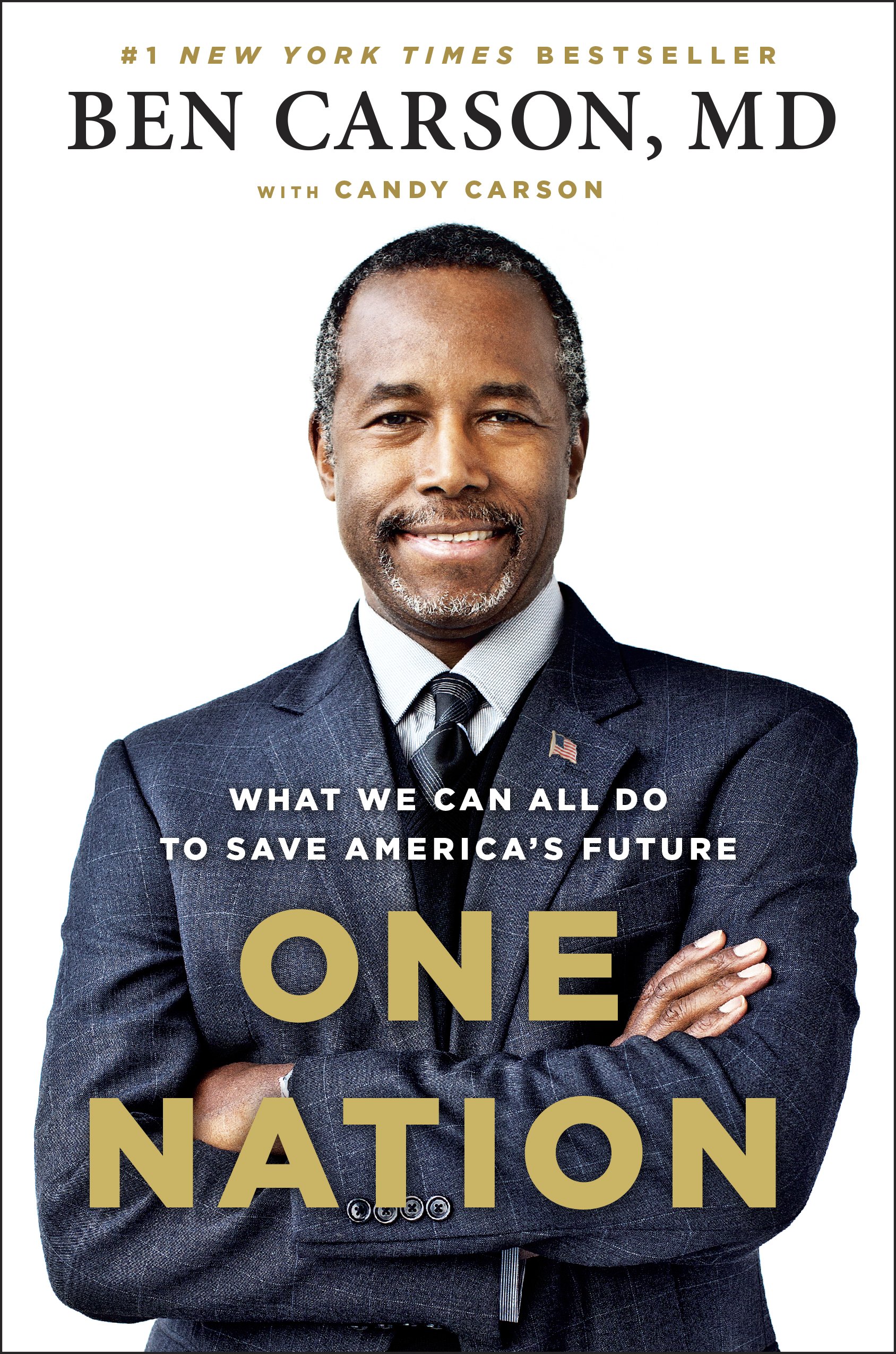

“God gets the credit for all the things I do,” Ben Carson said, sipping lemonade and picking at a salad. “But he also gets the blame. My job is to do the best that I can do.”

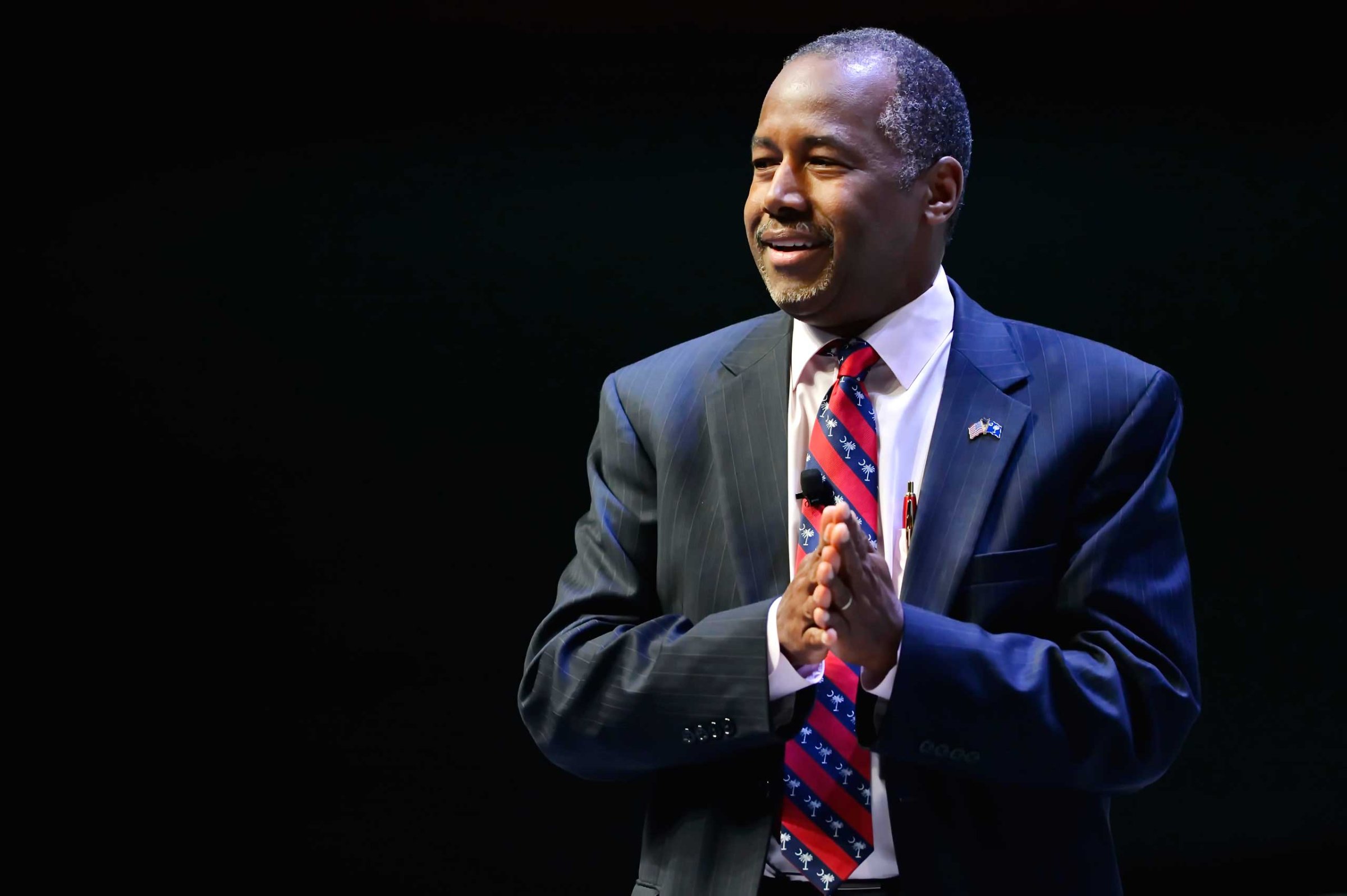

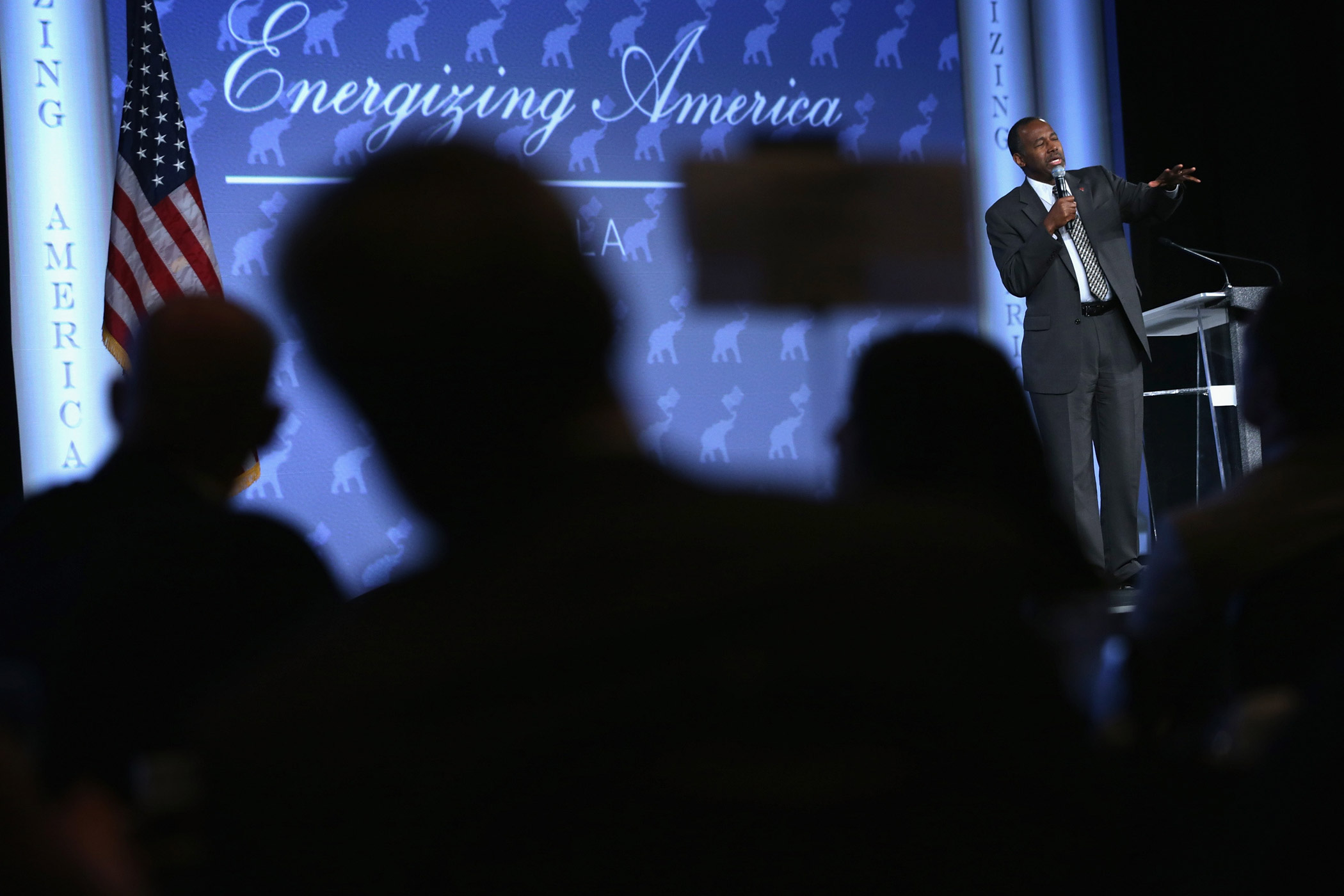

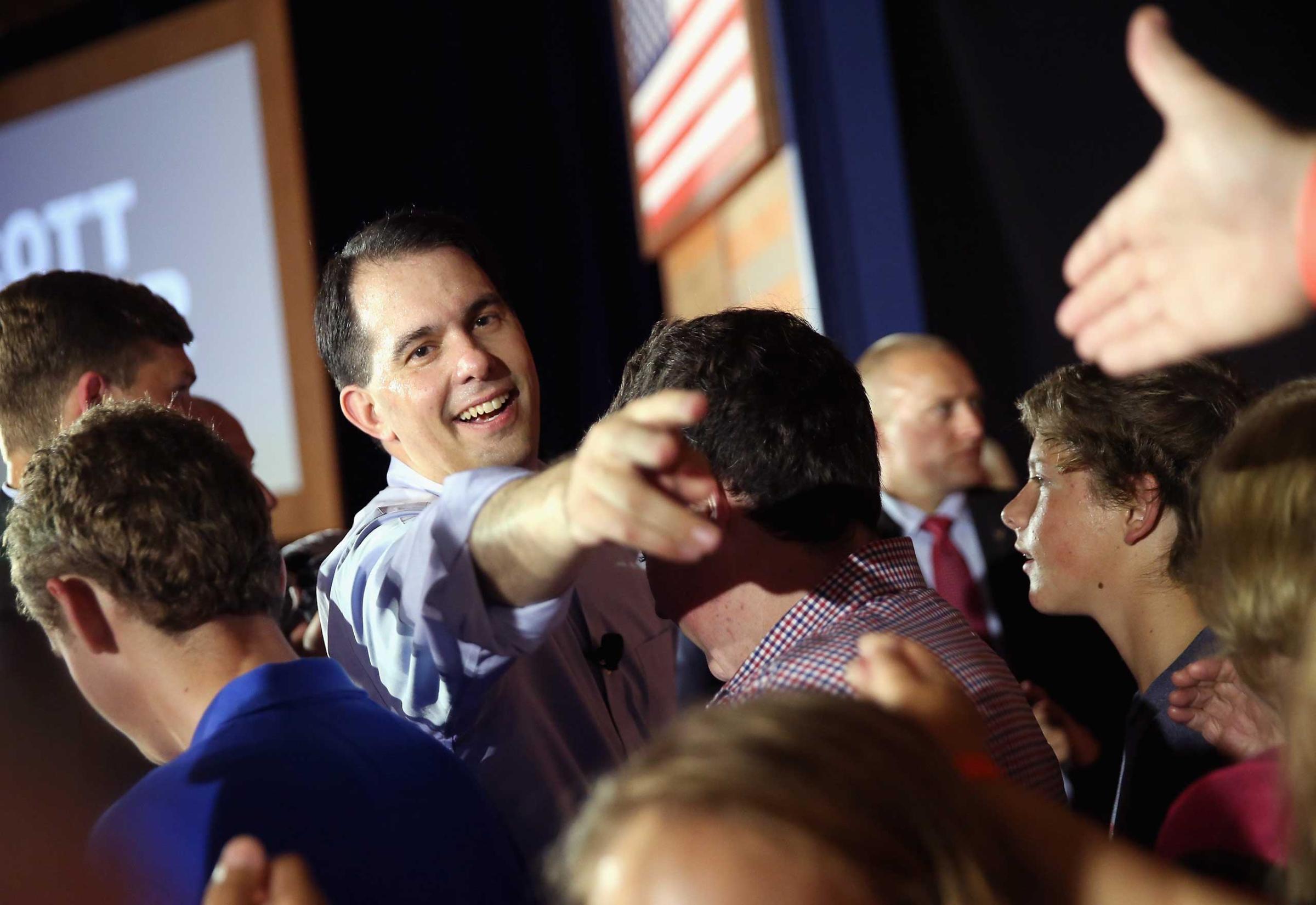

TIME sat down with Carson in Nantucket at the end of September for a wide-ranging interview that provided a window into his deep faith, the challenges he faced as a celebrated pediatric neurosurgeon and how he sees the road ahead as he surges to the top of the GOP field.

It’s a position he says he never really wanted in the first place, but one he felt called to by the people and by God.

Here is a lightly edited transcript of the interview.

You’ve had an amazing career as a surgeon. Why are you trying to come into politics now? Is there really no one else who could do the job?

It certainly was not my intention to go into the political field. But after the prayer breakfast in 2013, there were so many people clamoring for me to do it. And I kind of ignored it and figured it would all go away. But it didn’t. And it just kept building and building, and I began to listen to people and listen to their concerns. Particularly elderly people who told me that they had given up on America and they were just waiting to die. I heard that so many times. And then so many younger people who were terrified for what was going to happen with their children and grandchildren. And then I was hearing from so many people that they just didn’t feel that politics as usual was going to solve the problem. So having had a career as a problem solver, I said, Lord you know I don’t want to do this, but if you open the doors I’ll do it.

I know you’ve talked before about feeling that God wanted you to run. How did that factor into your decision?

I certainly wouldn’t want to do something like this if I didn’t feel that the Lord was behind it. And in a way I was comforted by listening to all the pundits who all said it’s impossible, you can’t do it, you can’t raise all the money, you can’t put together an organization, no one like you has ever done this, you can just forget about it. I said Phew! That’s good! [But] obviously all the pundits are wrong. Obviously He’s opening the doors.

Explain to someone who doesn’t know anything about brain surgery why that has something to do with being president.

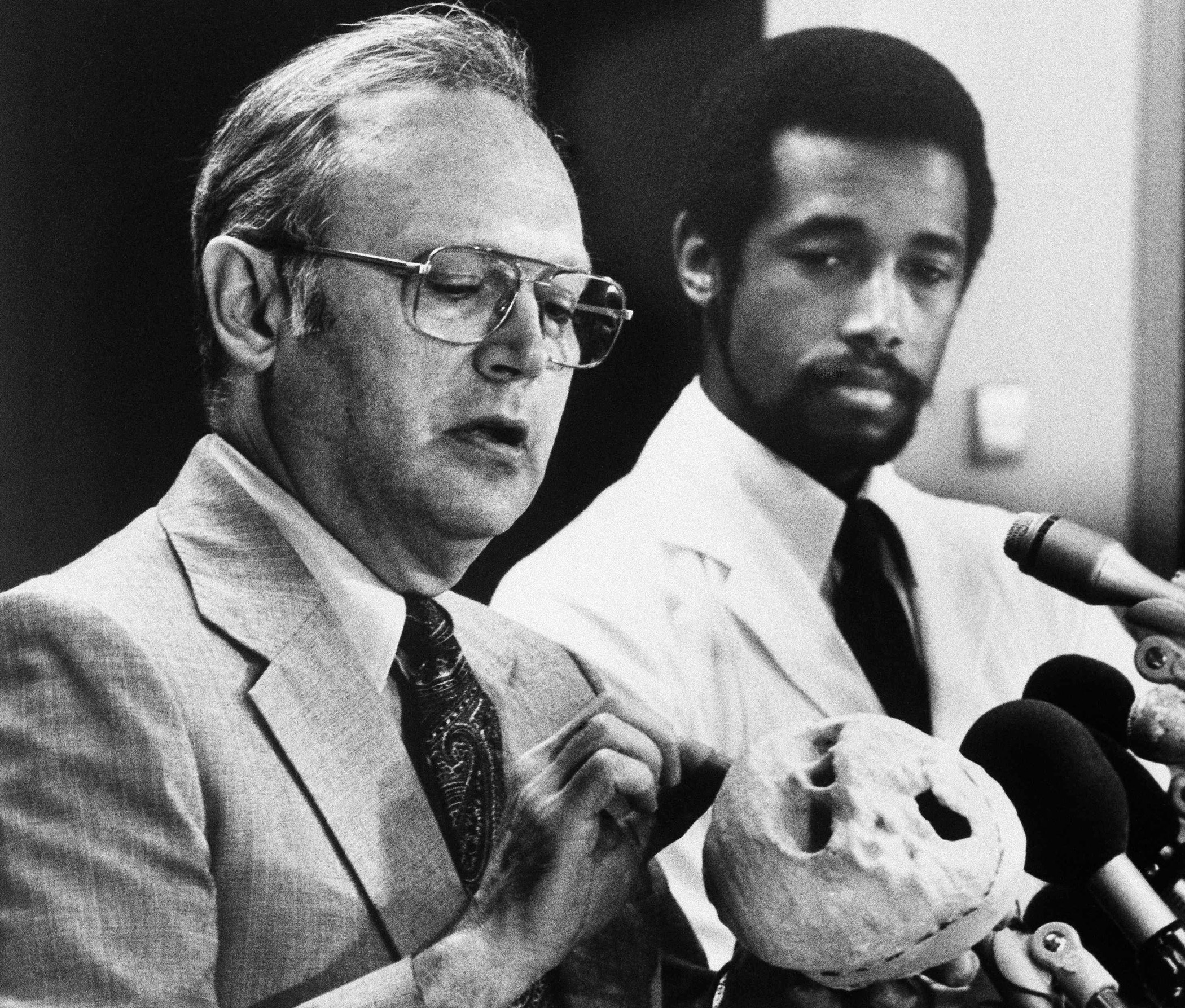

Because brain surgery is extremely complex. And sometimes you also have situations that require more than just your own expertise. What we’ve been able to do in many of those cases is bring together some of the best minds. These are not necessarily people who are devoid of ego, and to get them all on the same road, that’s how you accomplish things. In one case we decided to get 18 of the people in our department involved. Because I said we have the number 1 neurosurgery department in the country, and we have people who are extremely good at vascular neurosurgery, and tumor surgery, and skull base, and tissue, and I said why don’t we design this operation so that we slot each team in when we get to the part where they would be the expert? And we were literally ten hours ahead of schedule. It gives you a good example of what can be done when you don’t care who gets the credit. It really has to do with the ability to assimilate a lot of material, and make wise choices and use your resources in order to do that.

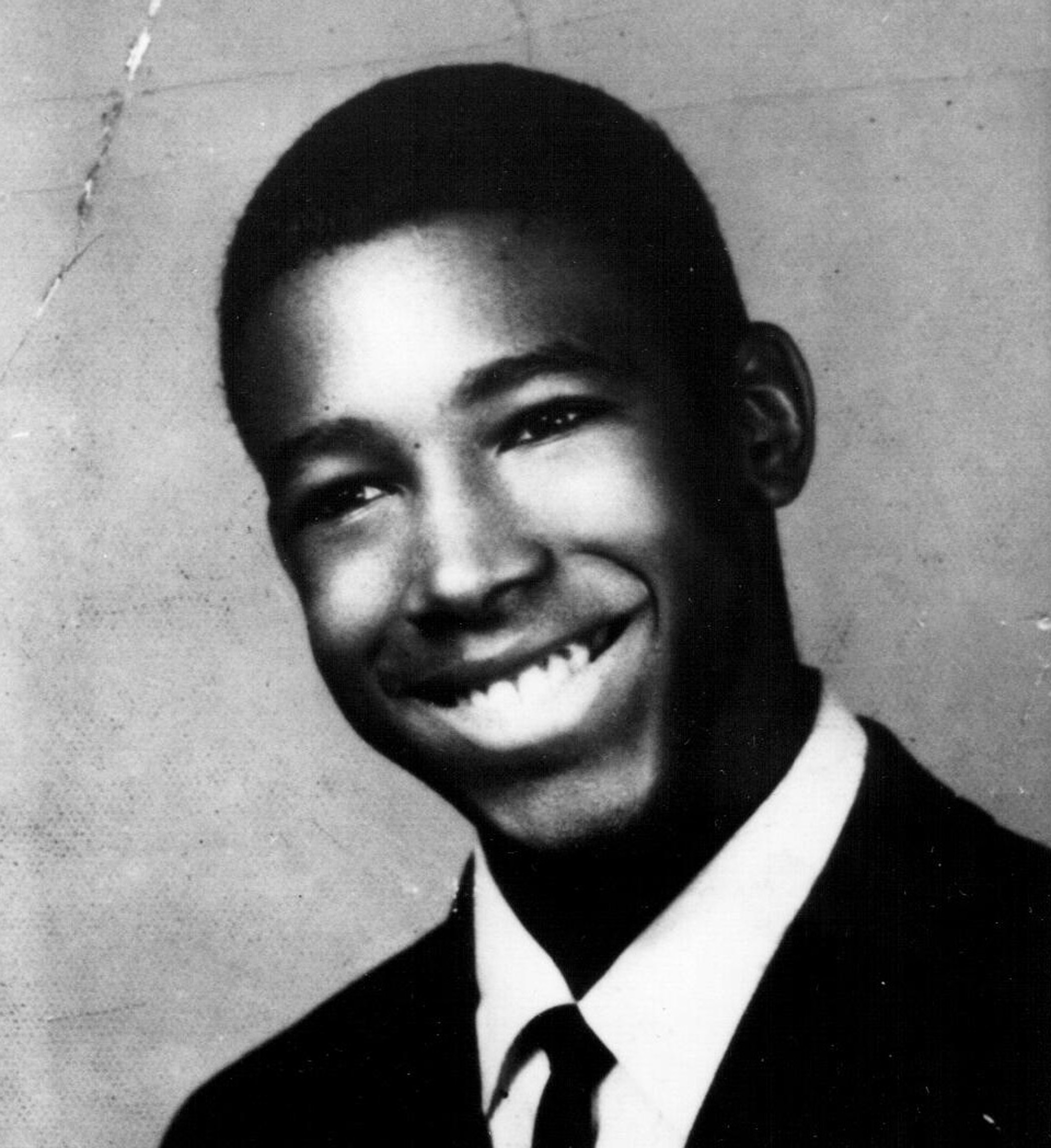

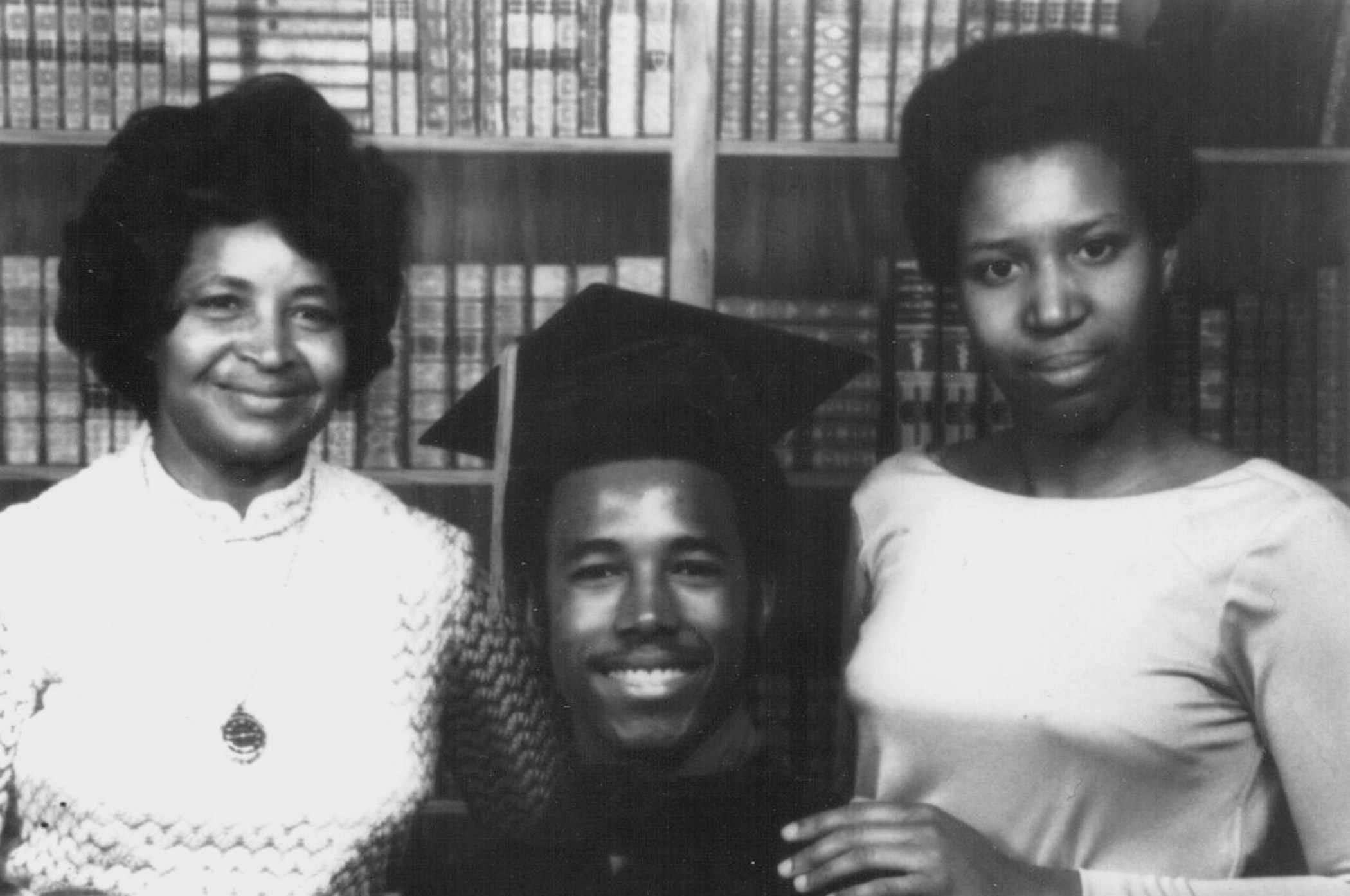

See Ben Carson's Life in Photos

But even though presidents have advisors, they are the person at the top who ultimately has to make the decision. How about a time where you were in charge and made a decisive choice yourself?

There have been multiple tumor cases, for instance, where they’ve been seeking opinions from lots of different places and been told that it’s too dangerous and can’t be done. And I remember one case in particular where it actually was an adult, but his wife was a nurse on the pediatric neurosurgery service, and none of the adult neurosurgeons would operate on him because the tumor had developed in his pons, which is in the brain stem, and it was too dangerous to take it out. And what you do in that situation is you explore all the possibilities. Radiation, gamma knife, there must be something that can be done. And all of those people had been consulted. But it came down to her finally, I couldn’t escape from her because she worked on the same floor, and she said you have to do this because nobody else will do it. And I said I’m a pediatric neurosurgeon. And she said well, he acts like a child! [laughs] I went and talked to him and I said you know there’s a 50/50 chance that you’ll die if I try and do this operation. And he said there’s a 100 percent chance I’ll die if you don’t do it. I said that sounds pretty mature.

The operation turned out OK. We got down to the brain stem and it was all covered over with vessels, vessels that were being recruited by the tumor. It was hard to even find that area that you could enter without interrupting those vessels. I finally found a little spot, and I could open up a very tiny hole under the microscope into the brain stem. You can’t open much of a hole because it’s like a coaxial cable. So I opened a small hole, introduced an instrument that I could feel for the consistency, because that’s the only way you’ll know when you actually hit the tumor, because it changes in consistency. And obviously you have to be spot on. And I felt the change in consistency, I grabbed it, I started trying to slowly tease it out. All of this is really being done by feel. Finally I could actually see the capsule, because it was a dark color, something called a hemangioblastoma, and as I started delivering it, the evoked potentials went flat. Those are the electrical impulses from the brain, sort of like a EKG. It flatlined. At which time the anesthesiologist said, “I told you this was a mistake, I told you you shouldn’t have done this. You killed him.” But his heart was still beating, so I continued to take the tumor out until it was completely out. Obviously we were at a very somber mood at that point because we weren’t expecting anything good. And closed him up, sent him to the ICU, intubated, not responding. So I went home somber. But I came back in the next morning and he was awake, he was extubated, he was cracking jokes.

So what do you think it was about you that you were willing to take on this surgery when no one else would?

Because I realized that if I didn’t do it he would die.

So other surgeons don’t make that same calculation?

Sometimes they don’t want to be the one who is involved in the death. But I’m thinking more in terms of him than I am of me. A lot of surgeons unfortunately in the environment that we live in now, [which is a] very litigious society, they’re thinking what if it goes wrong … It’s a tough situation to be in.

Of course not all surgeries are successful like that one was. How could you emotionally handle all that trauma?

My philosophy was do your best, and God will do the rest. So you’ll know if you’ve read any of my books, that God gets the credit for all the things I do. But he also gets the blame. My job is to do the best that I can do.

How do you see your faith in God and your career in science working together or opposing each other?

I see them working together. Fully recognizing that many people who claim to be scientists they say, well you can’t be a scientist if you believe in God. You believe God created the Earth, are you kidding me? You’re out of your mind. But that’s where faith comes in. Because people who believe that it all just happened, that takes a lot of faith too. Actually I think it takes more faith than what I believe. Particularly to believe that we evolved with the complexity of this brain from a pool of promiscuous biochemicals during a lightning storm, that requires a lot of faith, way more faith than I have.

There was a speech you gave in 2011 in which you seemed to imply that Darwin’s evolutionary theory was inspired by Satan – can you clarify that? I didn’t totally understand what you meant by that.

Well you wouldn’t understand it, no one would understand it unless they believe that there were forces of good and forces of evil. If you don’t believe that, then that would be a nonsensical statement to you.

But if you do believe that, what do you mean that the forces of evil were there?

I would believe that the forces of evil would be looking for a way to make people believe there was no God.

Ok. So do you not believe in evolution in the way that…

I believe in micro evolution. I believe in natural selection. But I have a different take on it. The evolutionists they say there, that’s proof that the theory of evolution is true. I say that’s proof of an intelligent and caring God who gave His creatures the ability to adapt to their environment so He wouldn’t have to start over every 50 years.

You tell audiences that your intelligence would help you make better decisions than our current leaders. Is intelligence at the same time limiting? Does it eliminate imagination?

I think it’s limiting if you don’t realize your limitations. Nobody knows everything, and you have to understand that and recognize as the Bible says in Proverbs 11:14: in the multitude of counselors is safety. And when you’re talking about the multitude of counselors you’re not just talking about people who agree with you. Because that’s what leads to bad decision making. You need to be able to put everything on the table.

Do you think intelligence is that easily translatable? You were a great surgeon and therefore you will be a great president?

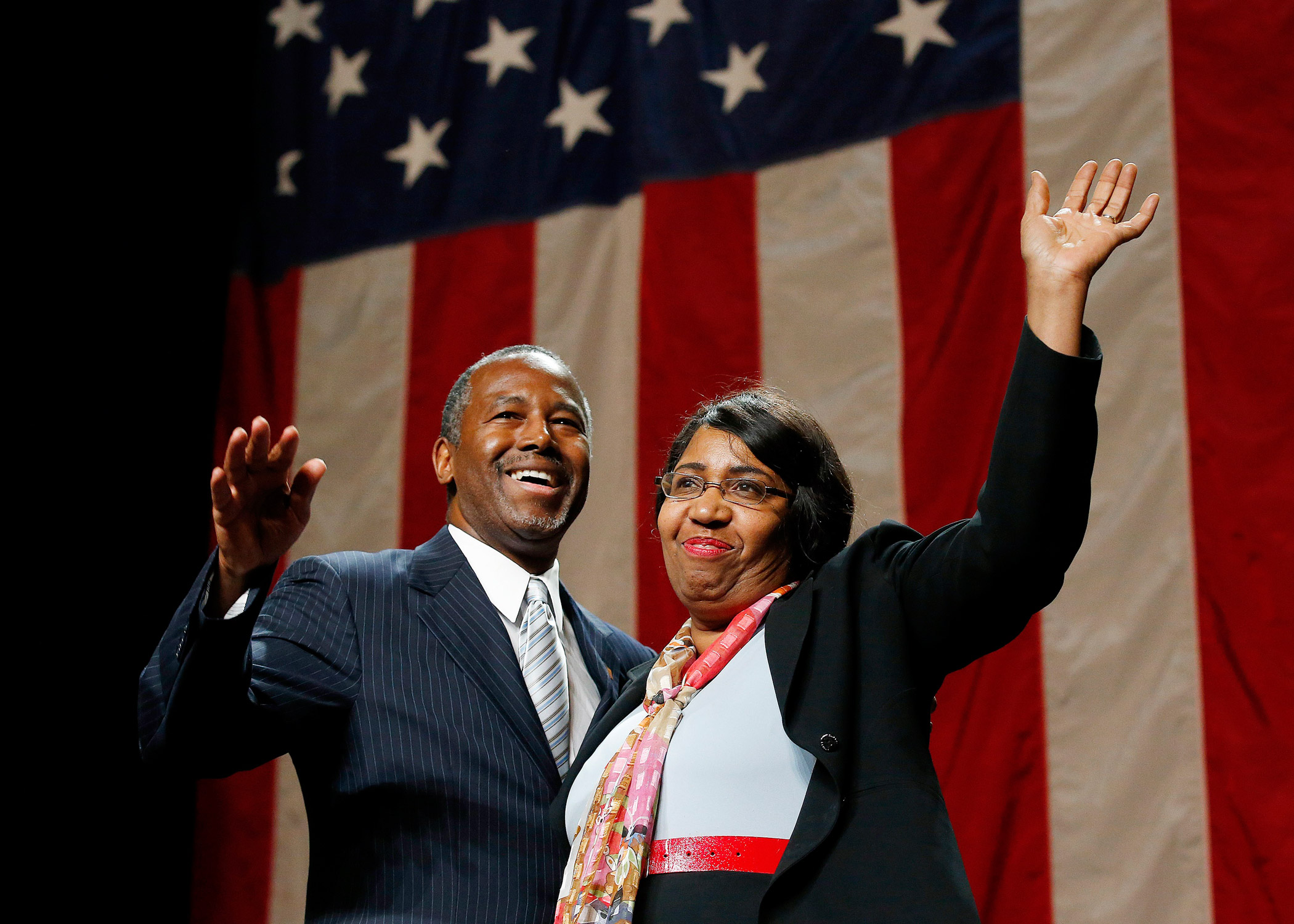

Yea, I do. Because you use it in lots of different areas. We used it when we started the Carson Scholars fund. Nine out of ten nonprofits fail. But Candy [his wife] and I put that together, and it’s active in all 50 states… It’s a matter of seeking wisdom. And when we put that together we didn’t do that all by ourselves. But we sought out the kind of people who would know what to do. And it made all the difference in the world.

Why do you think the Carson Scholars fund has been so successful?

You have to know what your goals are. That’s vital to ever being successful, you have to know where you’re going. And then you look at people who have already been successful and you find out what they did … They don’t even necessarily have to be famous people by any stretch of the imagination. They can just be people who have really made a big difference. In some cases they may be educators, because what we’re trying to do is inspire children. So that’s what I mean with a multitude of counselors.

Did you see Kanye West called you brilliant? He said he tried to call you – did you guys ever speak?

We did. We talked about some business principles. I was very impressed with his level of knowledge about business. And we talked about the hip hop culture and some of the messages that were sent, and how maybe it might be possible for him and some of the others to start thinking about ways to help young women in particular realize their self worth so they’re not giving themselves away to the first guy that comes along and then getting pregnant and their education stops and their kid lives in poverty. Just talked about things like that. He actually sang a song, a rap song, on the phone.

Do you feel a sense of duty to the African American community as a black Republican candidate? How does that play into your identity as a candidate?

Certainly knowing what a lot of people are experiencing and knowing how I managed to escape, I want people to benefit from that. That’s why I wrote Gifted Hands. That’s why I wrote Think Big. And a lot of people have, without question. That’s why I wanted the movie to be made in a certain way. I had at least 12 to 15 movie producers who wanted to make that movie. And I couldn’t agree on any of them because they all agreed on artistic license. And I said no, with my life you’re not doing that, because you know how they are. I’d be having an affair with some ICU nurse or something … I really wanted something that would truly be inspirational. I think they did a really good job. We went on the set and Cuba and everybody said you know, this is not a job for us. This is a mission. And they were really into it.

[Gifted Hands was made into a TV movie in 2009 starring Cuba Gooding Jr. as Ben Carson.]

So the candidacy just gives you a larger platform for getting out your story?

Right. So it was really for me, recognizing early on that it could be something that would be very inspiring to a lot of people who came from a similar background. It’s actually one of the reasons that I intentionally stayed in the background during the first conjoined twin separation. I didn’t want anybody to know that a black guy was the primary surgeon, because historically a lot of black people particularly in scientific areas who have accomplished things have been eclipsed and someone else took the credit. And I said boy, this could really be something that could inspire a lot of kids. So no one actually knew that I was the primary surgeon until after the operation was over at the press conference.

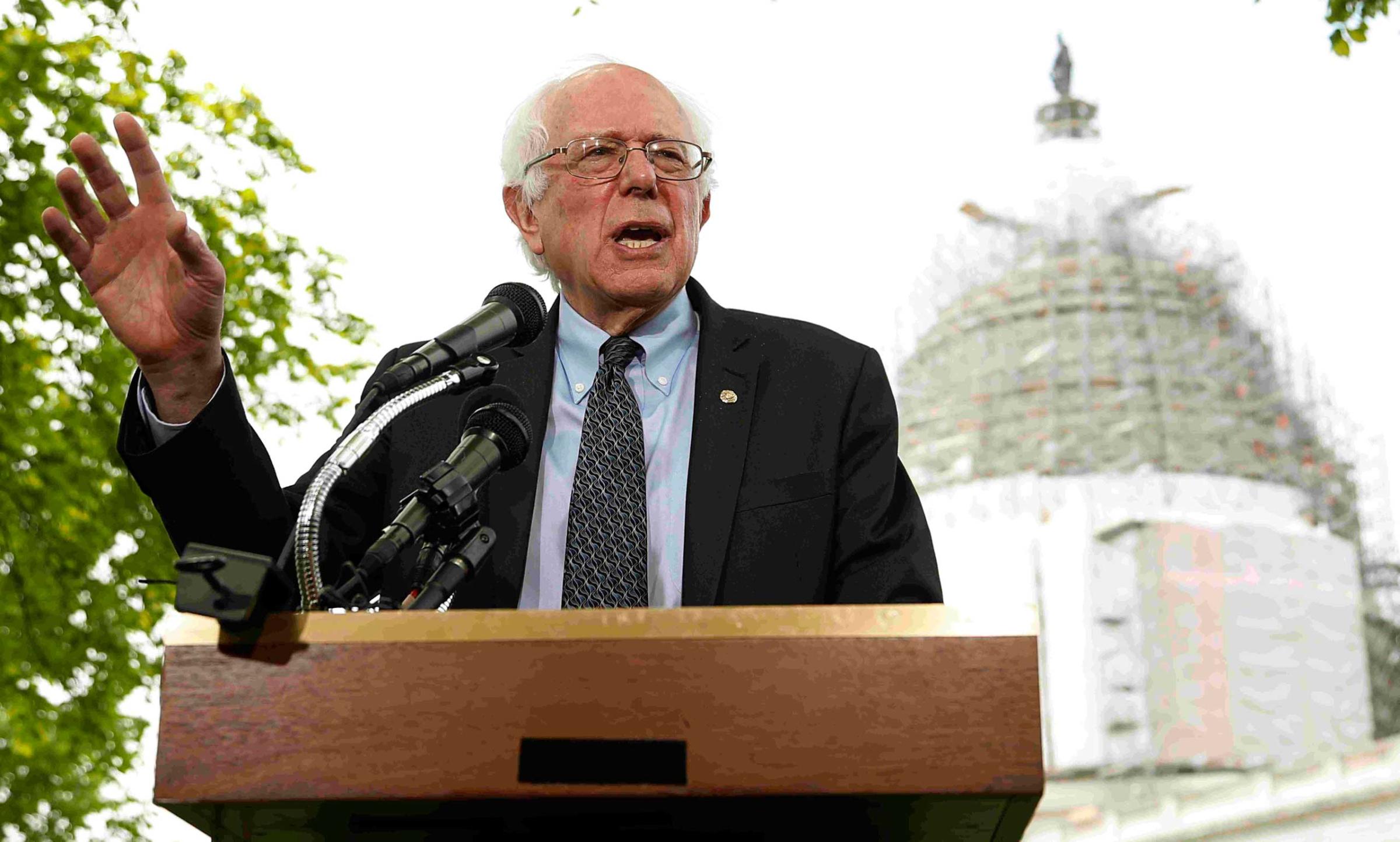

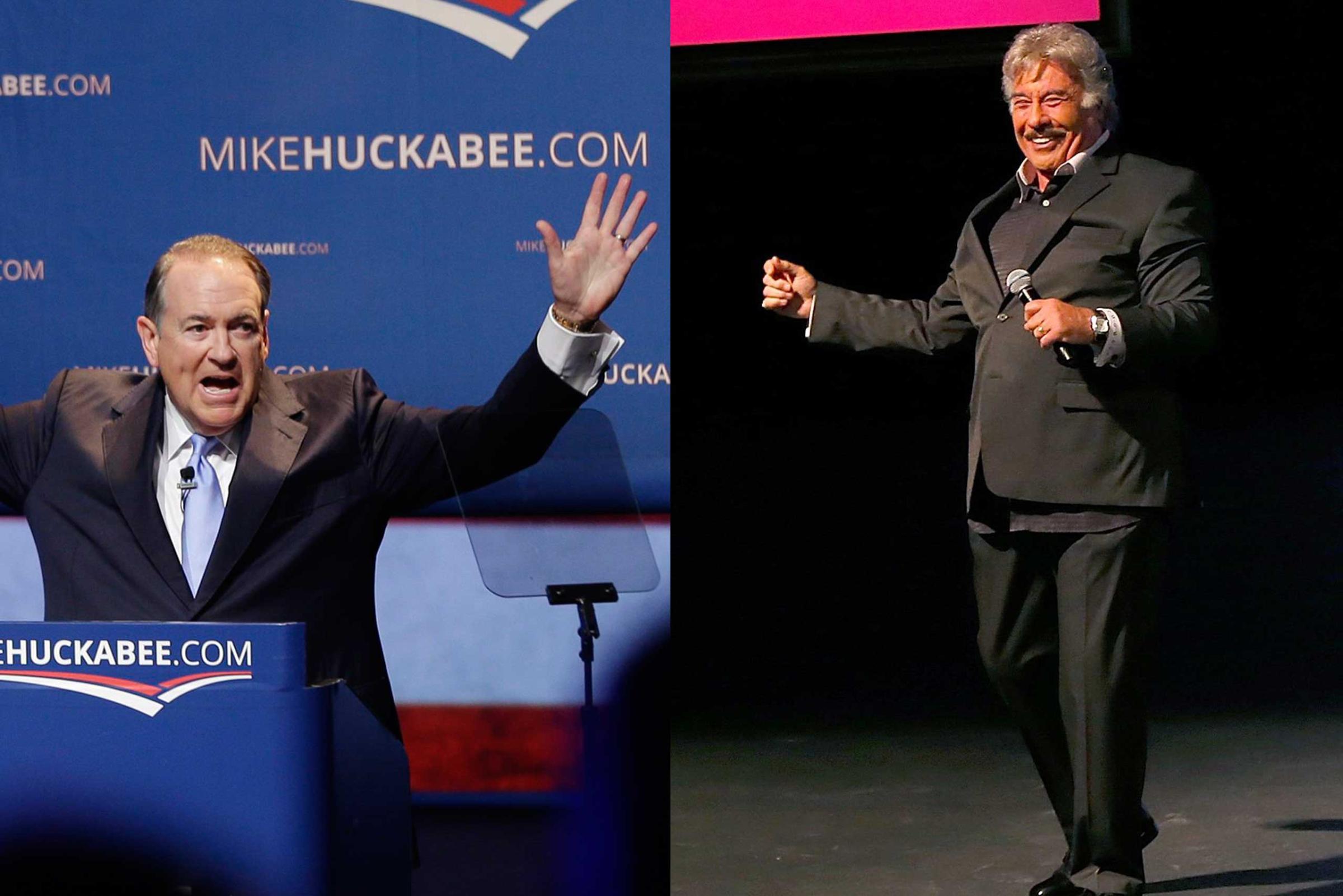

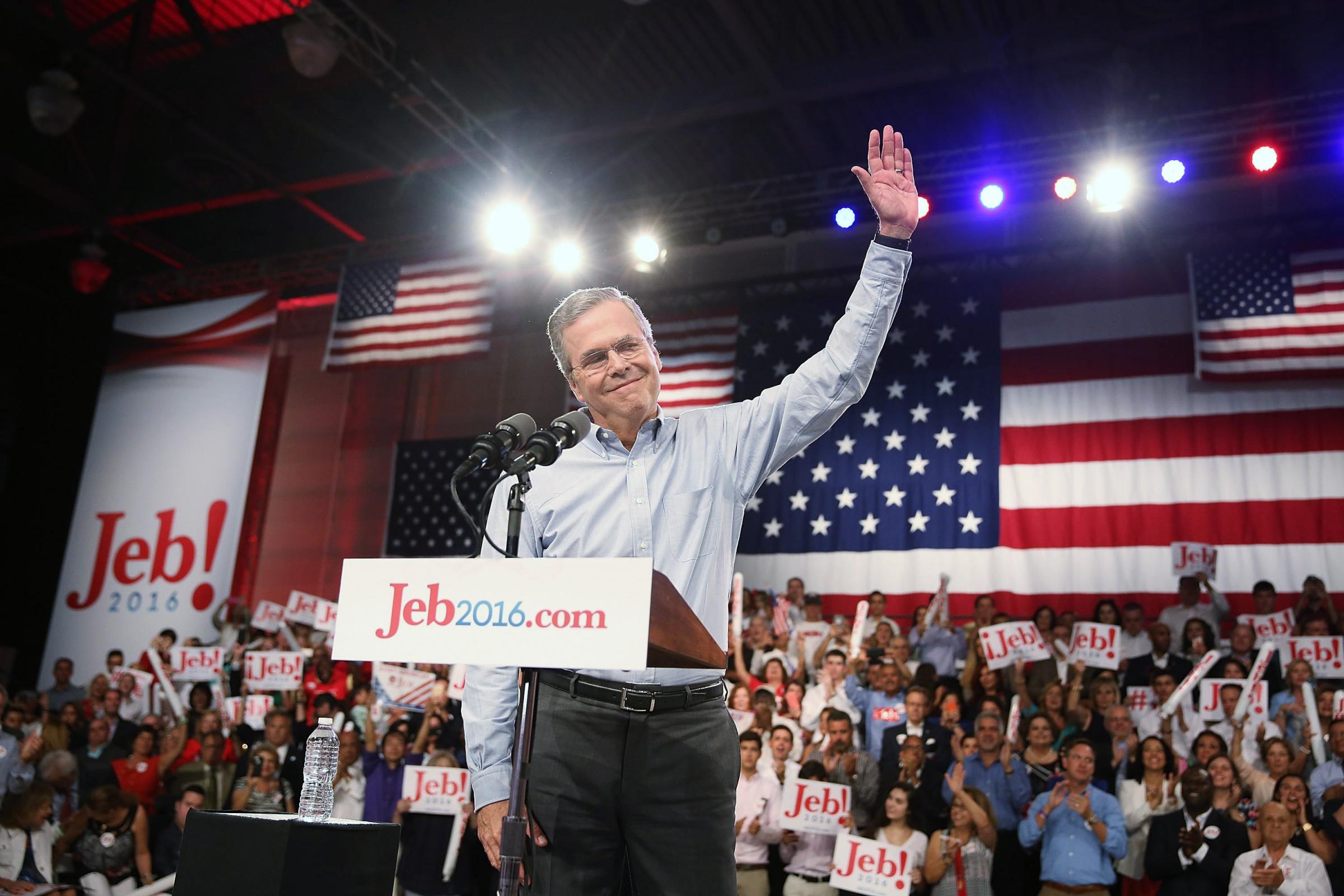

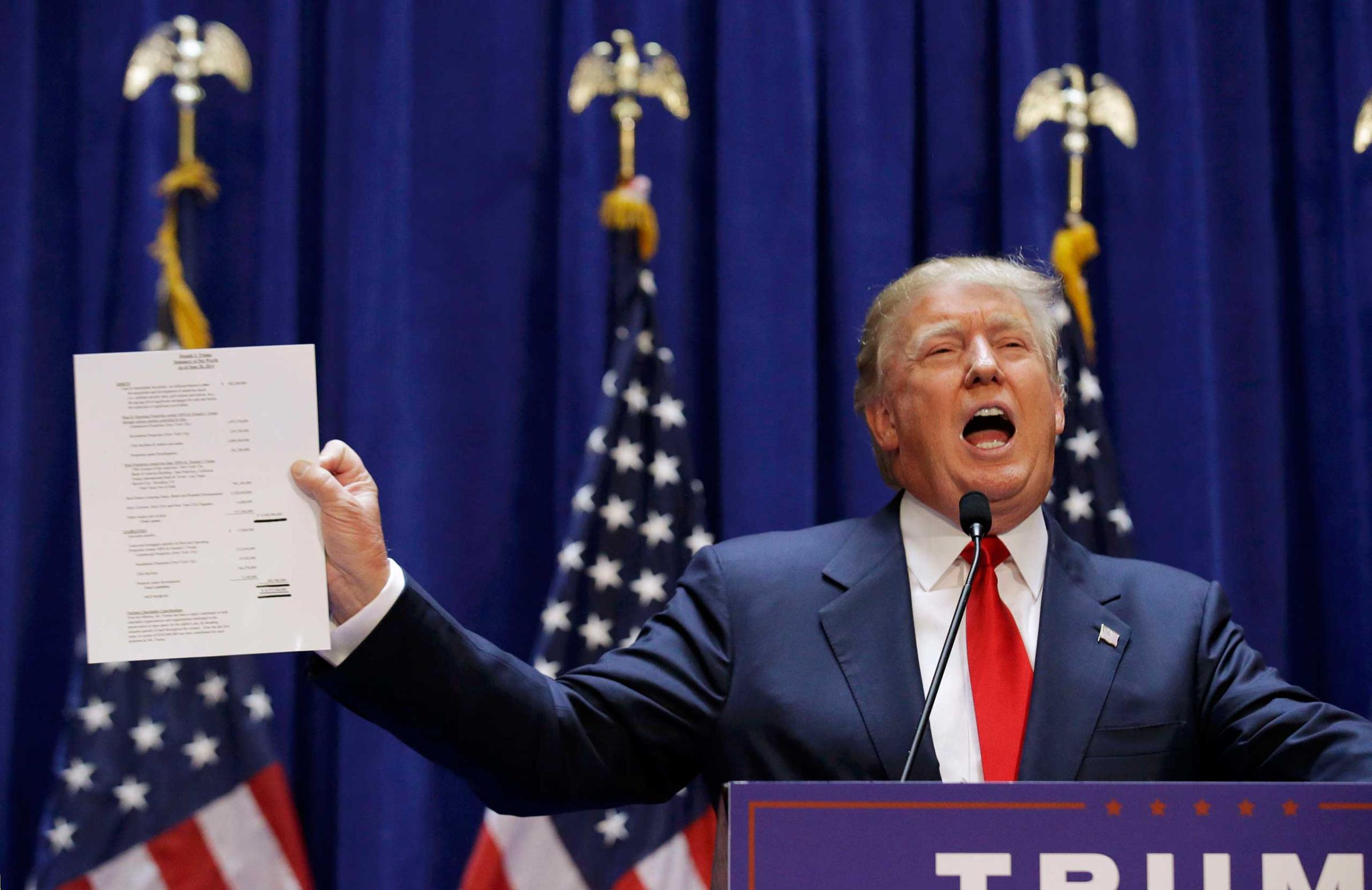

See the 2016 Candidates' Campaign Launches

There is such an appetite for an outsider that many of your past comments or positions have largely gone unnoticed. If you had come up through a traditional path—through Congress, for instance—you could have dealt with these in earlier campaigns. That would have allowed you to address them now as “old news.” Do you regret not having run for, say, the House?

No. Not at all. I simply don’t believe that to be a necessity. I think our country was designed for citizen statesmen, not for career politicians.

So do you think there’s no value to previous political experience when seeking higher office?

I think there can be. But considering that all of Congress if you add it all up there’s 8,700 years of experience, and I’m not sure that it’s helped that much.

In one comment you called President Obama a psychopath. You were a psychology major at Yale – did you mean this comment literally?

I said he was like a psychopath. We were really being rather light-hearted about it, talking about that, and we had no idea it was on the record.

You’ve also expressed skepticism about global warming – did you ever receive the thumb drive California Gov. Jerry Brown said he would send you of evidence for global warming?

No, I never got it. But it doesn’t matter because I’m very familiar with the various arguments. It’s just people can’t stand the thought of not having a fight. What I’ve said is it doesn’t matter about global warming or global cooling, at any point in time the earth is getting warmer or colder. That’s not the big factor. The big factor is we have a responsibility to take care of it. We have a responsibility to pass it on to the next generation in at least a good shape as we found it in. And our policies and our philosophies should be aimed towards that, not towards fighting each other.

So what do you think should be done now?

I think we should look at objective data that will inform us how we should do things. For instance, if there’s clear cut evidence that some manufacturing technique is causing a great deal of harm, then we ought to be looking at a different way to do it. Not necessarily shutting it down, because you look in Kentucky and some parts of Indiana and places where they just basically went in and shut down operations that were dependent on coal, and look what happened to all those people. So I would use the EPA to work with business industry and academia to find the cleanest, most environmentally friendly way to do things, rather than just alright, we’re coming in here and we’re shutting you down. I just don’t think that’s the smart way to do things.

In the recent GOP debate you got into it with Donald Trump on vaccines. He was taking the anti-vaxxer stance, but you didn’t exactly shut him down. You expressed concern over administering too many vaccines close together. Have you seen medical evidence that this is harmful?

I’ve seen evidence that a lot of parents are turned off by the intensity of the vaccination schedule. My point was that we in the medical profession don’t have to be like people in politics – my way or the highway. No compromise. You have to do it this way. I just don’t think that’s the wise way to do things. I think we need to look at other ways that we can group vaccines, and we have to be thinking about which ones are absolutely essential, and which ones people should have choice on.

TIME talked to the director of immunization at the CDC and he said children can receive up to 100,000 vaccines with no issues.

There can be an emotional issue to it. I just in general think we’ve become too coarse, and we need to consider people’s feelings.

So is that a bedside manner you’d bring to the White House as well?

Absolutely.

What do you think of John Boehner leaving? Who do you think should replace him?

He spent a lot of years in Congress providing public service, and I certainly in no way would want to denigrate what he’s done. Having said that, times they are a changin’. So you probably need a different type of leadership than his “go along to get along” leadership right now. I’m hoping that there will be a vigorous debate and that people will have an opportunity to really lay out their goals and their visions. I hope it’s not just a quick, “Ok, this is the next guy, put him in.” Because then we could end up in the same situation.

Can you shed some light on your relationship with the drug company Mannatech? Is it a company you still support?

It’s a company whose products I believe in and that I still take. I’ve been taking them for 13 years, I took some today. All of which I pay for. I’ve never had any kind of endorsement deal with them. In fact, I’ve insisted that I not have an endorsement deal with them. Although many of their associates have tried… I am not a spokesman for this at all, by any stretch of the imagination. And of course, you have people who are determined to somehow fit me into the difficulties the company has had in the past. I have nothing to do with it. Zero.

What have been your impressions of the Pope’s visit to America so far?

Well I was there [when Pope Francis addressed Congress], and I was just thinking, How cool is this. All this excitement not over an athlete, not over an entertainer, but over a man of faith. It gives you a lot of encouragement. Maybe we haven’t completely gone off the deep end.

What have you learned about yourself through the campaign process and taking on this new role?

I’ve learned that I don’t mind being attacked. I used to wonder about that. How would I respond to that, if people were attacking you all the time and telling lies. And I thought that I would not handle that well. But it doesn’t bother me at all. In fact, I’d probably be more bothered if they didn’t do it.

So how do you handle it in those situations when you’re being personally attacked?

I just kind of look at them and I say, can you imagine that used to be a cute little baby? I wonder what happened to that?

That’s what you do next to Donald Trump, you picture him as a cute baby?

(Nods and laughs)

So if you don’t become the nominee or don’t get elected, what next?

Then I can retire like I was planning in the first place. I would continue to write books, continue to do public speaking, probably get involved once again in corporate America. And learn how to play the organ.

Read Next: Inside Ben Carson’s Unlikely—and Uncommonly Spiritual—Campaign

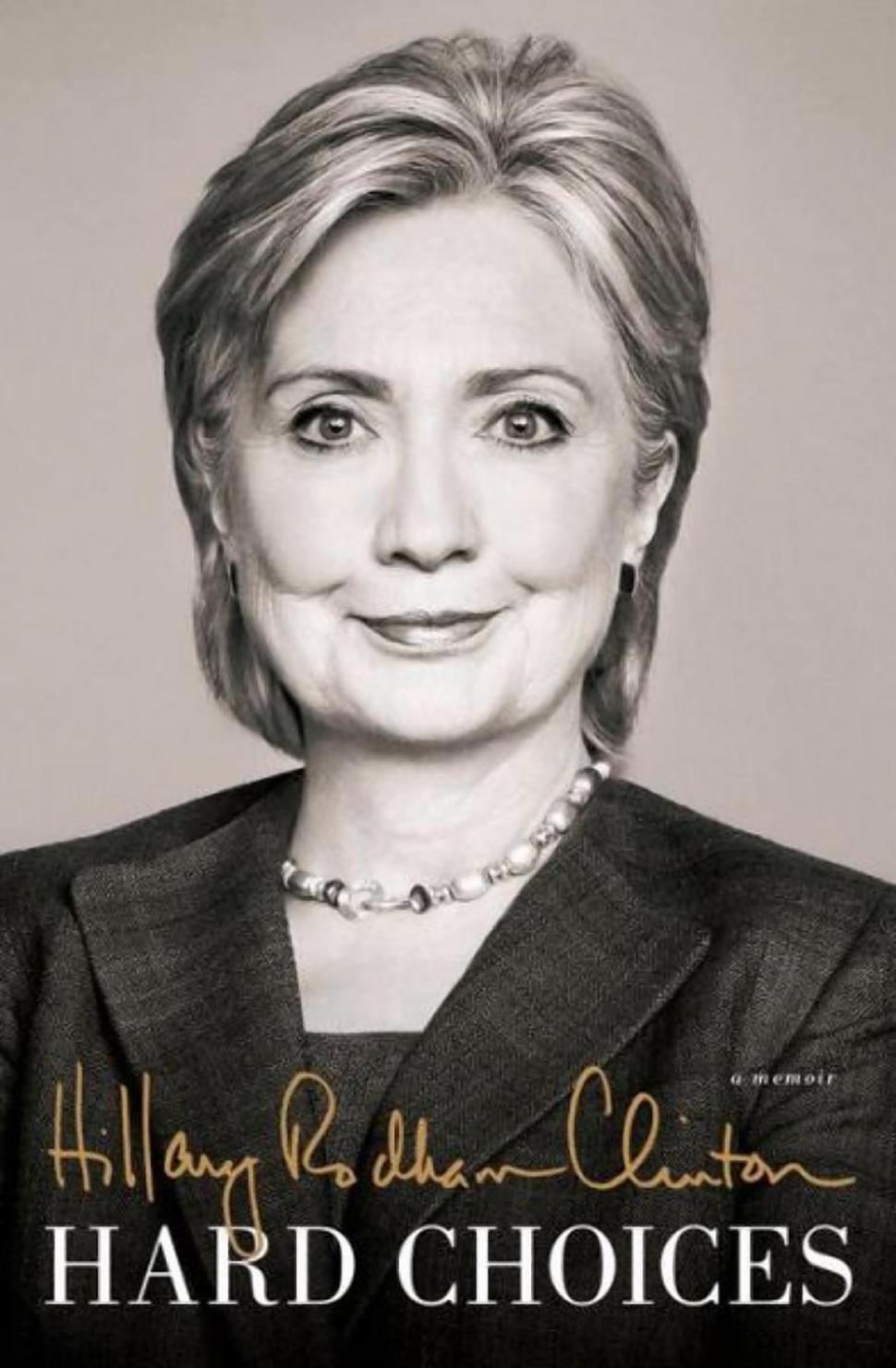

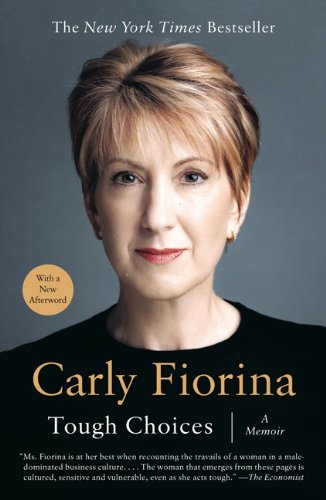

See the Covers of the 2016 Presidential Hopefuls' Memoirs

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Tessa Berenson at tessa.Rogers@time.com